Approach

Since women with endometriosis can present with a myriad of complaints, therapy should be individualised.[4] Clinical suspicion should guide therapy in the absence of positive findings for tests ordered during the assessment phase. Surgical diagnosis is not required before the initiation of empirical therapy. The primary objective of management should be to provide safe and effective care while minimising potential risks and addressing the woman's concerns, such as pain or fertility. A multi-disciplinary approach should be undertaken since the list of differential diagnoses is considerable, and often, no single intervention provides effective long-term therapy.

Treatment regimens outlined here do not always provide definitive relief from pain. Therapy should focus on reducing the risk of recurrent symptoms that may occur within a few months after completion of medical or surgical options.[55][56]

Medical management

For women without confirmed ovarian endometrioma, or without suspected severe or deep disease, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and hormonal contraceptives (combined oral contraceptive pills [OCPs] and progestogens) are generally regarded as first-line agents.[1] However, there is an increasing debate on the use of OCPs as first-line therapy because of concern over oestrogenic side effects and progression of more advanced stage disease. NSAIDs antagonise prostaglandin-mediated pain and steroid hormone-derived medicines suppress growth and activity of ectopic endometrial implants and induce amenorrhoea via the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. [

]

]

There appears to be positive feedback between prostaglandin (PG) synthesis, aromatase activity, and oestrogen production, mediated by abnormally high COX-2 activity in the setting of endometriosis.[57] Superficial, often atypical implants (seen more commonly in adolescents) are active PG producers. Since endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory condition, NSAIDs may improve symptoms of PG-associated inflammation and pain by interrupting receptor-mediated signalling pathways. In clinical trials, NSAIDs effectively treat primary dysmenorrhoea and provide adequate analgesia, but their use remains inconclusive for endometriosis-associated pain.[58][59] NSAIDs may be used alone or in combination with other medical therapies. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends paracetamol (alone or in combination with an NSAID) as an alternative first-line analgesic for women with endometriosis-related pain.[36]

Most hormonal options appear to be equally effective in treating endometriosis-associated pain.[60][61][62][63][64][65] Use is generally limited by lack of a response, bothersome side effects, or contraceptive implications for those who want to conceive.

OCPs are commonly used for cycle control and to suppress ovulation. If pain is strictly related to the menstrual cycle, then continuous use of the OCP can be recommended as women may become amenorrhoeic and will experience less cyclic pain.[66] Women should be made aware that irregular spotting is common with continuous use. Side effects are generally mild and time-limited. Life-threatening cardiovascular adverse events are more likely to occur in women aged over 35 years, who are heavy smokers, have acquired/inherited thrombophilia, or have experienced a prior cardiovascular event. Therefore, OCPs are not recommended for these women. Some reports indicate a reduction in anatomical relapse, and in the frequency and intensity of dysmenorrhoea recurrence with postoperative use of OCPs.[67][68][69] Clinical trials lack appropriate controls, and so the decision to prescribe OCPs is based on common practice guidelines rather than scientific evidence.[60]

OCPs can be prescribed in a cyclical or continuous fashion. While a continuous schedule with no pill-free interval may lead to reduced rates of dysmenorrhoea and postoperative endometrioma recurrence, side effects are more common.[70][71]

Progestogens (e.g., medroxyprogesterone, levonorgestrel, and dienogest) and antiprogestins have been shown to be as effective as other hormonal therapies, with varying degrees of tolerability.[61][72] [

]

As a result, there is increasing debate that progestin-only therapies be considered as first-line agents moving forward.[6][73] The levonorgestrel IUD is an effective treatment modality for long-term use, with improvement noted in staging and pelvic pain at 6 to 12 months of follow-up.[62][74] It can be used in the setting of advanced disease.[62][75] Similarly, there is increasing evidence that the etonogestrel-releasing subdermal implant improves endometriosis-related pain symptoms and quality of life.[76] Dienogest is an oral progestin approved for the treatment of endometriosis in Europe, Canada, and Japan, among other countries. It has been shown to reduce endometriotic lesions and provide symptomatic relief equivalent to gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (e.g., leuprolide), while also improving various quality-of-life measures.[77] It is not currently available in the US and some other countries, except in combination with estradiol valerate. However, this combination is sometimes used off-label for endometriosis. Some progestogens may decrease bone mineral density (BMD), especially with prolonged use. This effect may be more marked in adolescents, when the rate of bone mineralisation peaks. The subcutaneous form of medroxyprogesterone acetate, and IUD levonorgestrel, may reduce this risk.[55][75] Other unwanted side effects include weight gain, irregular uterine bleeding, and mood changes.

]

As a result, there is increasing debate that progestin-only therapies be considered as first-line agents moving forward.[6][73] The levonorgestrel IUD is an effective treatment modality for long-term use, with improvement noted in staging and pelvic pain at 6 to 12 months of follow-up.[62][74] It can be used in the setting of advanced disease.[62][75] Similarly, there is increasing evidence that the etonogestrel-releasing subdermal implant improves endometriosis-related pain symptoms and quality of life.[76] Dienogest is an oral progestin approved for the treatment of endometriosis in Europe, Canada, and Japan, among other countries. It has been shown to reduce endometriotic lesions and provide symptomatic relief equivalent to gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (e.g., leuprolide), while also improving various quality-of-life measures.[77] It is not currently available in the US and some other countries, except in combination with estradiol valerate. However, this combination is sometimes used off-label for endometriosis. Some progestogens may decrease bone mineral density (BMD), especially with prolonged use. This effect may be more marked in adolescents, when the rate of bone mineralisation peaks. The subcutaneous form of medroxyprogesterone acetate, and IUD levonorgestrel, may reduce this risk.[55][75] Other unwanted side effects include weight gain, irregular uterine bleeding, and mood changes. In the UK, NICE recommends that the patient should be referred (if not already) to a gynaecology service for further investigation and management, if initial pharmacological management (e.g., NSAIDs, paracetamol, and first-line hormonal contraceptives) is not effective, not tolerated or is contraindicated.[36]

GnRH analogues, including both agonists and antagonists, are typically offered if first-line treatments are ineffective, either alone or as an adjunct to surgery for deep endometriosis.[1][31][36][78][79][80][Evidence B][Evidence C] Some clinicians administer these agents as first-line therapy.

Elagolix is an oral GnRH antagonist that suppresses ovarian oestrogen production in a dose-dependent manner.[78] In the US, it is licensed for the treatment of moderate to severe endometriosis-related pain. Two 6-month placebo-controlled phase 3 trials reported significant reductions in dysmenorrhoea and non-menstrual pelvic pain among women with endometriosis-associated pain who were randomised to elagolix.[79] Hypo-oestrogenic adverse effects were similar to those of injectable GnRH agonists, and included hot flushes, increased serum lipids, and decreased BMD.[79] The maximum recommended duration of elagolix use is 6 to 24 months (depending on dose) to reduce the extent of bone loss.

Relugolix, another GnRH antagonist, is available in combination with estradiol and norethisterone, which are thought to reduce hypo-oestrogenic adverse effects.[80] In the US, it is licensed for the treatment of moderate to severe endometriosis-related pain. In two 6-month phase 3 trials, significantly more women who received relugolix combination therapy experienced improvements in dysmenorrhoea and non-menstrual pelvic pain, compared with those who received placebo.[80] The least squares mean percentage loss in lumbar spine and total hip bone mineral density was less than 1% after 24 weeks. Headache, nasopharyngitis, and hot flushes were the most common adverse effects.[80] The maximum recommended treatment duration for relugolix combination therapy is 24 months due to the risk for continued bone loss.

GnRH agonists induce a profound hypo-oestrogenic state, and may be administered for up to 12 months.[1] Approximately 85% of women with confirmed endometriosis will experience significant reduction in pain complaints.[82] Empirical use in women with chronic pelvic pain may also be considered, regardless of the diagnosis.[83] NICE advises that 3 months of pre-operative GnRH agonist treatment should be considered as an adjunct to surgery for deep endometriosis involving the bowel, bladder or ureter.[36] 'Add-back' hormonal therapy is indicated to reduce menopausal symptoms and the impact on BMD and should be offered at the beginning of treatment with GnRH agonists.[1][64][84][85] Non-hormonal forms of 'add-back' therapy to alleviate vasomotor symptoms include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitors, and various herbal remedies. GnRH agonists lack some bothersome side effects of progestogens and androgens and may be recommended prior to initiating other hormonal therapies, but they may not be well tolerated. Due to the effects on BMD, GnRH agonists may not be an ideal choice in adolescents. Results of one trial suggest that GnRH agonists have similar efficacy to that of continuous OCPs in treating endometriosis-associated pain.[86]

Danazol (a synthetic androgen) has been shown to be of subjective and objective benefit, but its use is limited by adverse effects that include darkening facial hair, acne, oily skin, deepening of the voice, and male-pattern hair loss.[63][87] Furthermore, reports have linked danazol to ovarian cancer.[88]

There is insufficient evidence supporting the use of pentoxifylline with respect to fertility and pain management in women with endometriosis.[89]

Surgical management with preservation of fertility potential

Surgical management is generally indicated for pain refractory to medical management, advanced disease, endometriomas, and associated sub-fertility. It may also be used to confirm endometriosis before initiating medical therapy; however, surgical diagnosis is not required to initiate medical therapy. Several studies have established a clear relationship between surgical intervention and reduction of pain in women with endometriosis.

[  ]

]

Exactly when to offer surgery is debatable and varies among specialists. It is usually determined by the individual clinician and woman. The patient’s symptoms, preferences and priorities regarding pain and fertility are elements that should be considered.[36] Side effects of hormonal therapy may influence the decision (e.g., in adolescents, it may not be ideal to initiate GnRH agonist or progestogen therapy because of potential impact on BMD at such a critical point in development). The ultimate goal is to minimise the number of surgeries for endometriosis. Therefore, empirical medical management is recommended before surgical management. If women are refractory to first-line agents, surgery may be considered because the probability of encountering true disease is higher. In women suspected of deep endometriosis or severe advanced disease based on symptoms and clinical findings, surgery can be considered before medical therapy.[90]

Ovarian endometriomas do not resolve in response to hormonal suppression and, if symptomatic, should be addressed surgically. There is insufficient evidence to determine whether hormonal suppression, either before or after surgery for endometriomas, is associated with any significant benefit compared with surgery alone.[91][92] However, there may be some benefit of prolonged hormone therapy because lower rates of dysmenorrhoea and endometrioma recurrence have been reported with continuous OCPs (compared with cyclical OCP) and progestin-only therapy after resection of endometrioma.[70][91][93]

Laparoscopically targeted destruction of implants and restoration of pelvic anatomy significantly reduces pain in the majority of women, although recurrence of disease and pain are not uncommon.[94][95]

Although laparoscopic findings do not always correlate with the degree of symptoms, pain seems to correlate well with the depth of peritoneal invasion.[96] Ablative therapy with electrosurgery or laser effectively provides relief (for at least 6 months) in women with minimal to moderate disease.[94] Radical excision of affected areas with restoration of normal anatomy is the preferred method of treating symptomatic women with deep peritoneal disease.[96][97]

Improvement in pain may last up to 5 years after surgery, but the risk of re-intervention approaches 50% in women with moderate to severe disease.[98] Less aggressive surgical measures and younger age are predictive of recurrence.[95][99] For this reason, prolonged hormonal suppression is recommended after surgery for endometriosis.[6][100]

Appendectomy may be considered in women undergoing laparoscopic surgery for suspected endometriosis if there is a complaint of right-sided pain and the appendix appears abnormal. Up to 50% of appendiceal specimens will yield abnormal pathology, but the effect on pain and future adverse outcomes is difficult to assess.[101]

Colorectal resection may be considered in women with intestinal disease and related complaints, although this remains controversial. A moderate-sized series demonstrated significant reduction in pain scores and improvement in quality-of-life assessments, yet major complications such as rectovaginal fistula formation (approximately 10%) occurred.[102] One meta-analysis found that disc excision was less associated with post-operative bowel stenosis, compared with segmental resection.[103] Rectal shaving may be considered for women with endometriosis that infiltrates the rectum, and is associated with fewer post-operative complications than disc excision or segmental resection.[103][104][105] Disc excision or segmental resection can be performed by laparoscopy or laparotomy, while preserving the uterus and adnexa for women who wish to have children.

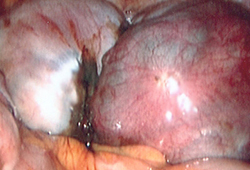

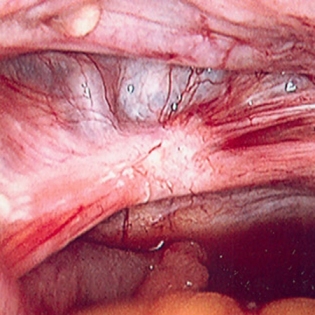

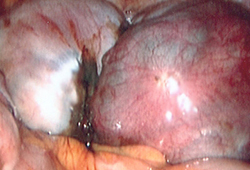

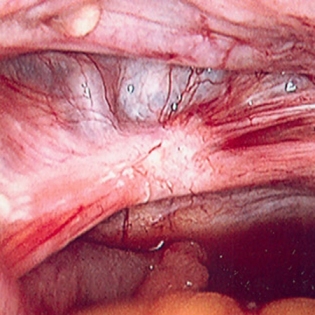

Benefit of surgery must outweigh inherent surgical risks such as bowel perforation and ureteral injury associated with adhesions and distorted anatomy. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic image of ovarian endometriomaFrom the collection of Dr Jonathon Solnik; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic image of endometriotic noduleFrom the collection of Dr Jonathon Solnik; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic image of endometriotic noduleFrom the collection of Dr Jonathon Solnik; used with permission [Citation ends].

Surgical management if continued fertility is not desired

Definitive surgical options for symptomatic women who have persistent pain despite conservative measures, and no longer desire childbearing potential, include hysterectomy with or without adnexectomy. For the best chance of cure, hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and excision of visible peritoneal disease should be offered, focusing on excising deep infiltrating lesions.[106] The principle is based on removal of common areas of implantation along with the primary source of endogenous oestrogen production. However, there is little distinction in the literature as to whether this is an effective treatment modality specifically for cyclical pain.[107] Although women with endometriosis may develop non-cyclical pain, a comprehensive pain assessment should be undertaken prior to offering hysterectomy to minimise risk of an unsuccessful surgery. Oestrogen replacement is generally warranted to reduce vasomotor symptoms and risk of bone loss, especially in pre-menopausal and symptomatic post-menopausal women. The risks (e.g., increases in risk of breast cancer, venous thrombosis and stroke in post-menopausal women) versus the benefits of hormone replacement therapy should be discussed with the woman before initiating treatment.

Endometriosis and sub-fertility

Endometriosis-related subfertility should be managed by a multidisciplinary team with input from a fertility specialist.[36] Sub-fertility associated with endometriosis can be treated with medical intervention (controlled ovarian hyper-stimulation), IVF, or surgical ablation of the endometrial implants. A Cochrane review demonstrated a lack of evidence to support ovulation suppression in sub-fertile women with endometriosis before they attempt to conceive naturally.[87] Further, in the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) does not recommend the use of hormonal treatment (either alone or in combination with surgical management) for patients with endometriosis who are trying to conceive.[36] They found mixed evidence as to whether combining hormonal treatment with surgery improves pregnancy rates, with some evidence showing no difference.[36] However, there is increasing evidence that GnRH agonist or progestin-only therapy before IVF may improve fertility outcomes.[108]

[  ]

The role of surgery is controversial since advanced reproductive technologies successfully treat infertility despite most disease state considerations. However, if the woman is symptomatic, surgery should be offered regardless of age. For women with or without severe disease who have failed IVF, surgery is probably indicated and endometrial implants should be adequately treated if noted.

[

]

The role of surgery is controversial since advanced reproductive technologies successfully treat infertility despite most disease state considerations. However, if the woman is symptomatic, surgery should be offered regardless of age. For women with or without severe disease who have failed IVF, surgery is probably indicated and endometrial implants should be adequately treated if noted.

[  ]

One meta-analysis of data from cohort studies found that women who had surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis before IVF were 2.2 times more likely to have a live birth, compared with unoperated women with deep infiltrating endometriosis who underwent IVF.[109]

]

One meta-analysis of data from cohort studies found that women who had surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis before IVF were 2.2 times more likely to have a live birth, compared with unoperated women with deep infiltrating endometriosis who underwent IVF.[109]

Controlled ovarian hyper-stimulation may be achieved in these women with ovulation induction medications, including a selective oestrogen receptor modulator (i.e., clomifene), an aromatase inhibitor (e.g., letrozole), highly purified gonadotrophins (also known as menotrophins), or recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone.

Although there is no consensus among experts, there has been a recent shift in the paradigm for those with sub-fertility and endometriosis. Many agree that IVF may be a more viable option for older women and those with multiple contributing factors to sub-fertility (e.g., endometriosis) when compared with surgery. Although IVF is costly it may be the most viable option for women with advanced endometriosis and sub-fertility; however, there are no validating, large randomised trials. Treatment of sub-fertility in the setting of advanced endometriosis is controversial, but it remains a viable option for women with advanced disease who are symptomatic or have failed previous IVF cycles.[110]

Laparoscopic surgery as the sole treatment of women with minimal to mild endometriosis may improve sub-fertility, but this remains an area of controversy that requires further research.[111] Repeat surgery for recurrent endometriosis may have less impact on the postoperative conception rate compared with that after primary surgery.[112] When counselling women with stage III/IV endometriosis (endometriomas), however, the decision to proceed with conservative surgical management should be based on symptomatology. If there is pain or a mass effect due to the endometrioma surgical excision is warranted. However, if the endometrioma is an incidental finding and the main concern is fertility, treatment may start with assisted reproduction. Excising the cyst wall is most effective in reducing pain and preventing cyst recurrence compared with drainage and ablation of the cyst wall.[113] However, NICE guidelines recommend that either of these techniques can be offered for endometriomas in patients who wish to prioritise fertility, taking into consideration the potential impact on the patient’s ovarian reserve (advising that laparoscopic drainage and ablation may preserve ovarian reserve more than cystectomy), and note that there was no evidence of an important difference in pregnancy rates between the two techniques for endometriomas larger than 3 cm.[36]

Risk of ovarian failure (reduced number of primordial follicles) after excising endometriomas is approximately 2.4%.[95] Sub-fertile women with endometrioma may show a diminished response to gonadotrophin stimulation, but the IVF success rates match those who deferred surgery.[114][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic image of ovarian endometriomaFrom the collection of Dr Jonathon Solnik; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic image of endometriotic noduleFrom the collection of Dr Jonathon Solnik; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic image of endometriotic noduleFrom the collection of Dr Jonathon Solnik; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer