Recommendations

Urgent

Be aware that patients may present to the emergency department with acute osteomyelitis, or with an acute flare-up of chronic osteomyelitis (duration varies accordingly).

Have a high index of suspicion as typical symptoms and signs may be absent. Ask about previous surgery or injury.

Adults present most commonly, but not exclusively, with acute-on-chronic osteomyelitis.

Children present most commonly, but not exclusively, with acute osteomyelitis.

Inform a senior colleague early if your patient is complex to manage (e.g., due to comorbidities).

Suspect osteomyelitis in an adult presenting with:

Fever, bone pain, reduced mobility, and local erythema, tenderness, warmth, swelling, and reduced range of movement.[2]

Suspect native vertebral osteomyelitis in a patient with:[7]

New or worsening back or neck pain and

Fever, or

Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP), or

Bloodstream infection or infective endocarditis

Fever and new neurological symptoms with or without back pain

New localised neck or back pain, following a recent episode of Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection.

Consider osteomyelitis in a patient with diabetes who has a local infection, deep wound, or chronic foot wound.[26]

Refer any person with a limb-threatening or life-threatening diabetic foot problem, including a clinical concern that there is a bone infection, immediately to the multidisciplinary foot care service.[26]

A patient with diabetes may not report pain due to neuropathy; hyperglycaemia that is difficult to control may be the only presenting feature.[26]

Any ulcer that probes to bone is at increased risk of having underlying osteomyelitis.[27][28]

Also consider Charcot’s arthropathy - a hot, painful foot in a diabetic may not be an infection. Refer to the interdisciplinary diabetic foot team if you are unsure of the diagnosis.

Suspect osteomyelitis in a child presenting with a short history (<1 week) of:

A limp or reluctance to weight bear, fever, bone pain, and local redness, tenderness, warmth, swelling, and reduced range of movement.[29]

Suspect chronic osteomyelitis in a patient with:

More vague, non-specific pain

Low-grade fever of 1 to 3 months’ duration

Lethargy and malaise

Persistent drainage from a wound and/or sinus tract.

Think 'Could this be sepsis?'

Refer to local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution for assessment and management of the adult patient with suspected sepsis.

Refer to local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution for assessment and management of a child with suspected sepsis. Seek senior advice early.

Key Recommendations

For any patient with suspected osteomyelitis, take initial blood tests, including:

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein.[6][7]

Microbiology samples (blood culture or bone biopsy) prior to commencing antibiotics, as this guides ongoing antimicrobial care.

The EANM/EBJIS/ESR/ESCMID consensus document for the diagnosis of peripheral bone infection in adults recommends considering taking blood cultures, especially if the patient has a fever.[2]

The European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID) guideline on bone and joint infections recommends taking blood cultures in children.[6]

The gold standard for accurate identification of the causative microorganism is culture of infected bone, as obtaining an aetiological diagnosis is important for choosing the appropriate antimicrobial treatment.[2]

There is a lack of consensus on whether bone samples should always be obtained (irrespective of ease of access) prior to commencing antibiotic therapy.

For any patient with suspected peripheral osteomyelitis, arrange for plain x-rays (anteroposterior and lateral, including the joint above and below the affected bone) to screen for osteomyelitis and exclude other pathology such as a fracture or bone tumour.

For the patient with suspected native vertebral osteomyelitis:[7]

Obtain two sets of bacterial (aerobic and anaerobic) blood cultures

Withhold antibiotics until microbiological samples (either blood or bone) have been obtained and their results have been reported, unless the patient is haemodynamically unstable and has signs of sepsis, or has evolving neurological symptoms.

Request a whole spine MRI.

For the patient with chronic osteomyelitis, do not send superficial skin swabs or aspirate from sinuses for microbiological processing.[30]

For a patient with suspected diabetic foot infection:[26]

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend that any patient with a diabetic foot problem is referred to and managed by a multidisciplinary team (see the Management recommendations section of this topic, or the Full recommendations section below); however they recommend the following initial investigations:

Sending a soft tissue or bone sample from the base of the debrided wound for microbiological examination. If you cannot obtain a sample from the base of the wound, take a deep swab because it may help determine appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Considering x‑raying the person's affected foot (or feet) to determine the extent of the problem.

If osteomyelitis is not confirmed by initial x-ray, consider an MRI to confirm the diagnosis.

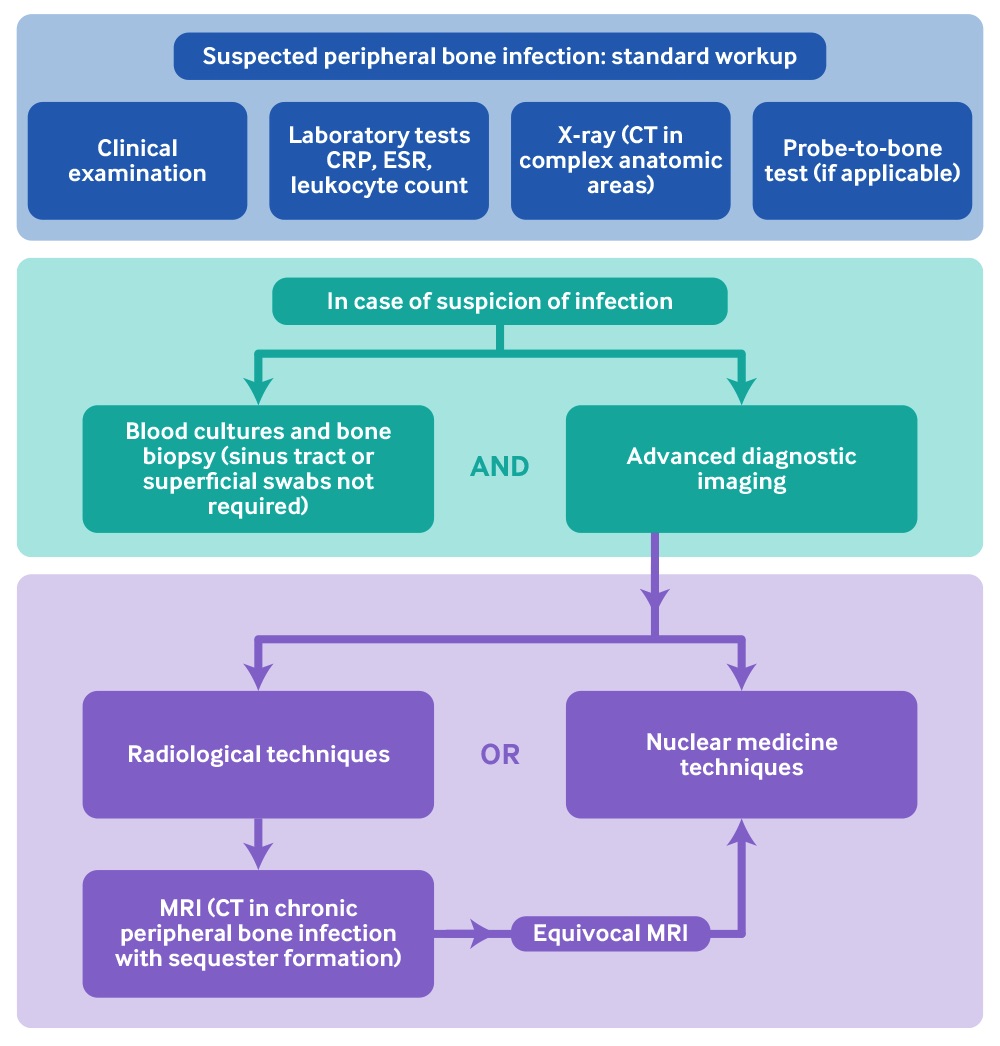

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Diagnostic flow chart of peripheral bone infectionAdapted from: Glaudemans AWJM, Jutte PC, Cataldo MA, et al. Consensus document for the diagnosis of peripheral bone infection in adults: a joint paper by the EANM, EBJIS, and ESR (with ESCMID endorsement). Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46(4):957-70. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ [Citation ends].

Have a high index of suspicion; diagnosis of osteomyelitis can be difficult as symptoms and signs are not universal.

Evidence: The evidence base for the diagnosis and management of osteomyelitis

Evidence-based guidance on osteomyelitis in the acute care setting is limited and patchy.[2][6][7][31]

The European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID) bone and joint infections guideline:[6]

Covers diagnosis and management of acute, haematogenous bone and joint infections in children.

The introduction to the guidelines states: “ESPID guidelines are consensus-based practice recommendations developed in a systematic manner that aim to be clear, valid and reliable, and presented with clinical applicability. Since evidence from large randomised controlled trials is rare or lacking, practice statements and recommendations provided here frequently reflect our expert consensus process based on best current practice.”

The guidelines are intended for health providers who take care of children with bone and joint infection, including general paediatricians and family practice physicians.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults:[7]

Includes evidence and opinion-based recommendations from the IDSA for the diagnosis and management of patients with native vertebral osteomyelitis treated with antimicrobial therapy, with or without surgical intervention.

The abstract states: “These guidelines are intended for use by infectious disease specialists, orthopedic surgeons, neurosurgeons, radiologists, and other healthcare professionals who care for patients with native vertebral osteomyelitis.

The European Bone and Joint Infection Society, European Society of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, European Society for Radiology, and European Association of Nuclear Medicine consensus document for the diagnosis of peripheral bone infection in adults:[2]

Reports on their systematic review of articles published on the diagnostic management of adult patients with peripheral bone infections, with special emphasis on radiological and nuclear medicine techniques.

Recommendations apply to a wide range of healthcare professionals, especially radiologists, nuclear medicine physicians, infectious diseases specialists, and orthopaedic surgeons.

The UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations investigation of bone and soft tissue associated with osteomyelitis:[31]

This Public Health England publication is a general resource for professionals practising in laboratory medicine and infection specialties in the UK.

It also provides clinicians with information about the tests available.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on diabetic foot problems: prevention and management:[26]

The guideline covers prevention and management of diabetic foot problems in children, young people, and adults with diabetes and includes care within 24 hours of hospital admission, or the detection of diabetic foot problems (if the person is already in hospital) and care across all settings.

Osteomyelitis is mentioned briefly.

In this topic, recommendations for diagnosis and management are referenced where possible, but much of the remaining content is based on expert opinion of what is generally accepted best clinical practice in the UK.

Be aware that patients may present to the emergency department with acute osteomyelitis, or an acute flare-up of chronic osteomyelitis (duration varies accordingly):

Adults present most commonly, but not exclusively, with acute-on-chronic osteomyelitis.

An acute presentation may be the first presentation of chronic osteomyelitis, or reactivation of a chronic osteomyelitis; previous infections may appear dormant for months or years before recurring.

Be aware of the possibility of native vertebral osteomyelitis in a patient with new back pain, fever, and raised inflammatory markers.[7]

Note that this is often a difficult diagnosis, in practice.

Paediatric spondylodiscitis (infection involving the intervertebral disc and adjacent vertebrae) is rare and accounts for 1% to 2% of all children with osteomyelitis.[6]

Children present most commonly, but not exclusively, with acute osteomyelitis. This presentation may be that of sepsis or pyrexia of unknown origin.

Children presenting with acute osteomyelitis are usually aged <5 years.[6]

Consider osteomyelitis if a patient with diabetes has a local infection, a deep foot wound, or a chronic foot wound.[26]

Practical tip

Make your definitive diagnosis based on clinical signs of infection, laboratory tests, imaging abnormalities, and the isolation of cultures from blood, joint fluid, biopsy specimen, or abscess fluid.[32]

Practical tip

Think 'Could this be sepsis?

See our topics Sepsis in adults and Sepsis in children.

Refer to local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution for assessment and management of the adult patient with suspected sepsis.

Refer to your local paediatric sepsis protocol.

Take a thorough history.

Ask about:

The duration of symptoms

Recent travel to, or residence in tuberculosis (TB)-endemic areas

Previous TB

Previous osteomyelitis

Previous trauma (open fracture, surgery, or penetrating injury)

Immunosuppressive medication

Immunisation history in children (particularly important to know whether they have received the Haemophilus influenzae type B [Hib] vaccination)

Risk factors which increase the risk of osteomyelitis including:

Previous osteomyelitis

Penetrating injury

Intravenous drug misuse

Diabetes

HIV infection

Recent surgery

Distant or local infection

Sickle cell disease

Rheumatoid arthritis

Chronic kidney disease

Immunocompromising conditions

Upper respiratory tract or varicella infection (in children).[6]

Note a short history (<1 week) of symptoms that might indicate acute osteomyelitis such as:

Limb deformity

A limp or reluctance to weight bear in children

Fever

Initially, 30% to 40% of children will not develop a fever[6]

Bone pain

May be non-specific pain at the site of infection

Local erythema and swelling

Reduced range of movement

Sinus or wound drainage

Malaise and fatigue

Recent incidental trauma (e.g., bumped leg)

Infections (e.g., skin or urinary tract).

In children, make a probable diagnosis of osteomyelitis/joint infection in the presence of (based on results from a survey of European paediatric specialists):[32]

At least 1 of 4 clinical signs:

Fever >38°C (>100.4°F) and local inflammation

Suspicion of osteoarticular infection

Reduced mobility

Joint swelling.

And at least 1 of:

Positive blood culture

Purulent joint fluid

Positive culture from bone or joint aspiration

Imaging findings consistent with a bone or joint infection.

Bear in mind that the following may suggest native vertebral osteomyelitis:[7]

New or worsening back or neck pain and

Fever, or

Elevated ESR or CRP, or

Bloodstream infection or infective endocarditis

Fever and new neurological symptoms with or without back pain

New localised neck or back pain, following a recent episode of S aureus bloodstream infection.

Patients most at risk of native vertebral osteomyelitis are those who:

Are elderly

Are immunocompromised

Are active intravenous drug misusers

Have indwelling central catheters

Have undergone recent instrumentation.

Be aware that the following history may suggest chronic osteomyelitis:

More vague, non-specific pain

Low-grade fever of 1 to 3 months’ duration

Lethargy and malaise

Persistent drainage from a wound and/or sinus tract.

In practice, have a high index of suspicion in a patient with diabetes with a hot inflamed foot.

Be aware that a patient with diabetes may not report pain due to neuropathy; they may present only with hyperglycaemia that is difficult to control.[26]

Refer the patient to the multidisciplinary foot care service within 24 hours of the initial examination of the patient’s feet.[26] See our topic Diabetic foot complications.

Immediately inform the multidisciplinary foot care service about any person with a limb-threatening or life-threatening diabetic foot problem, including a clinical concern that there is a bone infection.[26]

Note that any ulcer that probes to bone is at increased risk of having underlying osteomyelitis.[27][28]

Also consider Charcot’s arthropathy - a hot painful foot in a patient with diabetes may not be an infection.

Involve the multidisciplinary foot care service as it can often be difficult to distinguish between infection and Charcot’s arthropathy in a patient with a diabetic foot problem.

Examine the patient generally, and clinically assess the affected area.

Note any abnormal vital signs such as a fever, or signs of sepsis. See our Sepsis in adults and Sepsis in children topics. Refer to your local sepsis protocols.

Examine the cardiovascular system to identify murmurs that may indicate endocarditis as a source of haematogenous spread.

Look for the following signs of acute or acute-on-chronic osteomyelitis:

Local inflammation, erythema, tenderness, and swelling

Areas of point tenderness

Decreased range of motion above and below the affected area

This may be due to pain, or may indicate an associated septic arthritis.

Torticollis and low back pain may indicate axial osteomyelitis, or lumbar discitis.

Be careful to recognise signs that indicate native vertebral osteomyelitis:[7]

Paravertebral muscle tenderness and spasm, and limitation of spine movement - the predominant physical examination findings

Pain that:

Is localised to the infected disc space area

Is worsened by physical activity or percussion to the affected area

May radiate to the abdomen, hip, leg, scrotum, groin, or perineum

Spinal cord or nerve root compression and meningitis, which may occur

Neurological signs, which occur more commonly with cervical or thoracic involvement.

Practical tip

Be aware that osteomyelitis of the vertebrae or pelvis may present without any localising signs and with systemic symptoms alone.

In older adults, the urinary tract may be a source of infection from gram-negative organisms in cases of vertebral osteomyelitis.[37]

Torticollis can be secondary to cervical vertebral osteomyelitis.[33][34]

Note the following signs of chronic osteomyelitis:

Typically low grade fever

Angular deformity or shortening of the limb that may have resulted from premature fusion of the physeal plate (particularly following childhood osteomyelitis)

Acute or old healed sinuses

Fracture fixation

Evidence of previous operations, including scars and previous flap designs

Tenderness to percussion over the subcutaneous border of affected bones.

Think about osteomyelitis if a person with diabetes has any of the following:[26]

A local infection with erythema more than 2 cm around an ulcer

A deep foot wound, involving structures deeper than skin and subcutaneous tissues

A chronic foot wound with local infection

Local infection with a temperature of >38°C (>100.4°F) or <36°C (<96.8°F), increased heart rate, or increased respiratory rate.

Practical tip

A patient with diabetes may not report pain due to neuropathy; they may present only with hyperglycaemia that is difficult to control.

In a patient with diabetes, if you can palpate the bone with a probe, this is indicative of osteomyelitis; however, there is no evidence to support the utility of this in diagnosing peripheral bone infection in a patient without diabetes.[2] Be careful with a probe-to-bone test as it can cause harm.

There are no specific blood tests to confirm the diagnosis of bone infection.

Base your diagnosis primarily on evidence of osteomyelitis from plain x-rays and microbiological cultures.

Biochemistry and haematology

Always take a white cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) in any patient with suspected osteomyelitis.[2][6]

Note that inflammatory markers such as the white cell count, ESR, and CRP are usually raised, but they have a low specificity for osteomyelitis.[2][6]

Assess for improvement after treatment has started, using the trend in blood inflammatory markers such as ESR and CRP. Be aware that inflammatory markers are:

Often normal or only mildly elevated in chronic infection or in patients with a diabetic foot problem.[26]

Non-specific and may be raised in other conditions such as inflammatory joint disease and gout.

A persistently elevated ESR after treatment should trigger further assessment.[38][39][40][41][42]

CRP may be more helpful than ESR because CRP normalises more rapidly after successful treatment.

Practical tip

A patient with diabetes may not report pain due to neuropathy; they may present only with hyperglycaemia that is difficult to control.

In a patient with diabetes, if you can palpate the bone with a probe, this is indicative of osteomyelitis; however, there is no evidence to support the utility of this in diagnosing peripheral bone infection in a patient without diabetes.[2] Be careful with a probe-to-bone test as it can cause harm.

Microbiology

Take all microbiology samples (blood culture or bone biopsy) prior to commencing antibiotics; use the results to guide ongoing antimicrobial care.

Blood

If blood cultures are indicated, obtain samples before initiating antibiotics, whenever possible.[2][6]

In adults, consider taking blood cultures, especially if the patient has a fever, in line with the recommendations made in the EANM/EBJIS/ESR/ESCMID consensus document for the diagnosis of peripheral bone infection in adults.[2]

In children, take blood cultures, in line with the ESPID bone and joint infections guideline recommendations.[6]

For a patient with suspected native vertebral osteomyelitis, obtain two sets of aerobic and anaerobic blood cultures.[7] Consider:

Obtaining serological tests for Brucella species in a patient with subacute native vertebral osteomyelitis residing in, or recently returning from, an area endemic for brucellosis[7]

Obtaining fungal blood cultures in a patient with suspected native vertebral osteomyelitis who is at risk for fungal infection (epidemiological risk or host risk factors)[7]

Requesting a purified protein derivative (PPD) test (also known as an intradermal Mantoux test) or obtaining a serum interferon-gamma release assay in a patient with subacute native vertebral osteomyelitis and at risk for Mycobacterium tuberculosis native vertebral osteomyelitis (i.e., originating, living in, or recently returning from TB-endemic regions, or with risk factors).[7]

Bone samples and bone biopsy

There is a lack of evidence and consensus on whether bone samples should always be obtained (irrespective of ease of access) prior to commencing antibiotic therapy.[2]

If a patient has suspected sepsis, do not delay antibiotic therapy.[2] See the Clinical presentation section above, and our topics Sepsis in adults and Sepsis in children. Refer to your local sepsis protocols.

If the patient is less sick, balance the invasiveness of the test with the need for an accurate aetiological diagnosis. Biopsies through sinus tracts are not recommended.[2]

The gold standard for accurate identification of infection and the causative microorganism is culture of infected bone. Obtaining an aetiological diagnosis is important for choosing the appropriate antimicrobial treatment.[2]

When indicated, obtain bone specimens from open bone biopsy, image-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA), or needle puncture. Bone biopsy is usually performed during the surgical debridement procedure.[2] FNA is less disruptive to bone than biopsy and allows multiple samples to be taken.[2] Be careful to prevent infection spreading to uninfected bone.[2]

Obtain for microbiological examination a soft tissue or bone sample from the base of the debrided wound in patients with diabetes and a foot problem, because this may inform the choice of antibiotic treatment.[26]

If you cannot obtain a sample from the base of the wound, take a deep swab.[26]

Bone biopsies are generally conducted using CT guidance. MRI is rarely used for obtaining a bone biopsy because of the electromagnetic radiation MRI-guided bone biopsy requires.[2] In selected patients (e.g., children) consider MRI-guided bone biopsy with a non-ferromagnetic stainless steel needle.[2]

Collect at least three bone biopsy samples from a visibly inflamed area to reduce incorrect contamination reports.[2]

Divide collected samples for bacteriology and histology.[2]

Request aerobic and anaerobic cultures.[2]

Consider cultures for mycobacteria and fungi in patients living in or having visited endemic areas and with suggestive clinical features.[2]

Swabs

Do not send superficial skin swabs or aspirate from sinuses for microbiology sensitivity and culture because these have been shown to correlate poorly with the causative organism.[30] Aspirate deep fluid collections. Obtain for microbiological examination a soft tissue or bone sample from the base of the debrided wound in patients with diabetes because it may inform the choice of antibiotic treatment.[26]

If you cannot obtain a sample from the base of the wound, take a deep swab.[26]

In acute infection, direct microscopy with Gram staining of aspirated fluid gives a rapid indication of the type of organism present (e.g., gram-positive cocci) but base continued treatment on full culture results with antibiotic sensitivities.

Practical tip

In chronic osteomyelitis:

Gram stain has a very low sensitivity and is of no practical use

In relation to implant-related infection, percutaneous biopsy is often negative.

To maximise the sensitivity of microbiological sampling, the patient should stop antibiotics for at least 2 weeks before surgical debridement. The false-negative rate from cultures in osteomyelitis rises from 23% to 55% if antibiotics are given with 2 weeks of sampling.[43]

Surgery samples

If surgery is indicated, take multiple microbiology samples at the start of any debridement surgery.

The gold-standard diagnostic microbiological test in chronic or device-related osteomyelitis requires taking multiple deep samples under aseptic conditions using separate instruments to improve the sensitivity and specificity of the culture results.

Take at least five samples with fresh, sterile sampling instruments for each sample.[44][45]

In chronic or device-related bone infections, prolonged cultures for aerobic and anaerobic organisms of 7 to 10 days are needed to identify slow-growing organisms such as Propionibacterium species. Mycobacteria may take even longer. Inform the laboratory of any unusual features so that appropriate culture techniques can be employed.

For example, an immunocompromised patient should have culture for Nocardia species, mycobacteria, and fungi.

Mycobacterial cultures at 25°C (77°F) may be needed if Mycobacterium marinum is suspected (an extremity infection related to tropical fish tank exposure or aquatic environments).

Sonication is used to increase microbiological sensitivities by subjecting hard surfaces such as plates, screws, implants, or bone removed during surgery to ultrasonic energy while in a sterile saline solution. This releases organisms from the biofilm and improves culture rates in low-grade implant infections where the bacterial load may be small.[46]

Mantoux test

Request a purified protein derivative (PPD) test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis for a patient originating from or living in a TB-endemic region, or with risk factors.

Molecular methods

These may be helpful in identifying organisms when culture is negative or when antibiotics have been given prior to taking microbiological samples.[6]

Nucleic acid amplification techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are highly specific and sensitive for rapidly identifying bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses from clinical samples, including those that are slow to grow or cannot be cultured.[31]

Results are available particularly quickly if multiplex real-time PCR is used.

PCR has been shown to be more sensitive than conventional culture when identifying some fastidious organisms (e.g., Kingella kingae) and PCR-hybridisation after sonication can improve diagnosis of infections related to implants.[31] However, the sample needs to be big enough to ensure sensitivity. PCR does not provide antibiotic susceptibility information.

Can identify Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) genes.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

Request 16s ribosomal protein profiles obtained by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation - time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry to identify bacteria and yeasts quickly and effectively.[31]

Mass peaks achieved by the test strains are compared with those of known reference strains.

Imaging

Plain x-ray

Always request x-rays in suspected peripheral osteomyelitis to look for evidence of osteomyelitis, as well as other pathologies such as fractures and bone tumours.[2] After careful clinical examination of the joint above and below the affected area, request imaging of the joint if you have any clinical suspicion of septic arthritis. See our topic Septic arthritis.

In acute osteomyelitis the initial x-ray may look relatively normal.[47] By 6 to 7 days, osteopenia may be visible. Evidence of bone destruction, cortical breaches, and periosteal reaction follow quickly. Involucra may start to appear at this stage. Sequestra can sometimes be seen as early as 10 days. As time goes on, diffuse osteopenia is seen secondary to disuse of the affected limb.

In more established chronic infection, intramedullary scalloping, cavities, and cloacae may all be seen. A 'fallen leaf' sign indicates a piece of endosteal sequestrum that has detached and fallen into the medullary canal. However, in patients with a diabetic foot problem, the x-rays may look normal.[26] If osteomyelitis is not confirmed by initial x‑ray, consider an MRI.[26][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plain x-ray of the left femur showing a lytic lesion in the medullary canal along with a 'fallen leaf' sign with intramedullary sequestrum noted in the cavityCourtesy of the Oxford Bone Infection Unit [Citation ends].

Practical tip

In children, ask for the x-ray to include the joint above and below the area of pain to exclude an alternative diagnosis such as a slipped capital femoral epiphysis causing pain and limp. See our topic Slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

In children with discitis, lateral spine radiographs show late changes at 2 to 3 weeks into the illness, especially decreased intervertebral space and/or erosion of the vertebral plate. In children with vertebral osteomyelitis, localised rarefication (‘thinning’) of a single vertebral body is seen initially, and then later, anterior bone destruction is observed.[6]

Consider a chest- x-ray if you suspect tuberculosis.[31] See our topic Extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

Bone MRI

MRI is usually the most definitive and helpful imaging modality after x-ray.

Interpretation of MRI scans in osteomyelitis can be challenging. Seek advice from a radiologist with a special interest in musculoskeletal imaging.

MRI gives good cross-sectional information about the bone and the surrounding soft tissues.[48][49][50][51]

High signal on the T2 images or fat suppression sequences may be seen, indicating infection in the medullary canal or surrounding soft tissues.

MRI tends to overestimate the extent of infection in the acute phase when bone oedema is seen as high signal in the medullary canal.

Sequestra appear black on all MRI sequences, as does normal cortical bone. Therefore, MRI is not very good at detecting cortical sequestra.

MRI after surgery can be difficult to interpret because postoperative changes can persist for months or years and may be misinterpreted as persistent infection.

Imaging is also severely degraded by the presence of metalwork, which is commonly present in contiguous focus osteomyelitis.

Metal Artefact Reduction Sequences (MARS) can be used to minimise the artefact; however, there will still be some degradation of the imaging.

Request whole spine MRI for a patient with suspected native vertebral osteomyelitis.[7]

Bone MRI can detect abnormalities in children within 3 to 5 days of onset.[6] It may be indicated when:

The child is very sick

You have doubts about the diagnosis

You suspect a complication.

Ultrasound

If readily available, MRI scanning is the imaging modality of choice; however, use ultrasound to drain any collections identified on MRI or to obtain a microbiology sample.

Computed tomography

Use computed tomography (CT) to aid surgical planning.

CT has a limited diagnostic role and exposes the patient to radiation.[51]

CT is better at assessing the extent of bone destruction and abscesses, and can identify small sequestra more reliably than MRI.[52][53][54]

Aspiration of subperiosteal or intraosseous spaces under fluoroscopy- or CT-guidance helps guide antibiotic treatment.

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography or single-photon emission CT scanning may be considered when an abnormality is seen in the bone on MRI and it is difficult to determine whether it represents active infection or simply structural derangement of the bone. It is useful in the presence of implants, when MRI may be hard to interpret.

Local availability, preference, and experience are the primary factors in determining whether to use CT or MRI.

Bone scan

For the patient with suspected native vertebral osteomyelitis, when MRI is not feasible (e.g., with implantable cardiac devices, cochlear implants, claustrophobia, or unavailability), consider a combination spine gallium/Tc99 bone scan, or CT scan, or a positron emission tomography scan.[7]

Echocardiogram

Identify valvular vegetations with an echocardiogram. This may help to confirm bacterial endocarditis.

Histology

If taken, always send any bone samples for histology, as some bone tumours may mimic features of osteomyelitis.

Deep histological sampling helps interpretation of microbiological sampling results. Some infections, such as tuberculosis and actinomycosis, can be diagnosed by histology alone, and it is helpful to know that the culture was negative in these instances.

Histology can confirm the diagnosis of culture-negative osteomyelitis by the demonstration of acute and chronic inflammatory cells, as well as dead bone, active bone resorption, and the presence of small sequestra.[55]

For the patient with suspected native vertebral osteomyelitis (based on clinical, laboratory, and imaging studies), obtain an image-guided aspiration biopsy if an organism (usually S aureus, Staphylococcus lugdunensis, and Brucella species) has not been identified by blood cultures or serologic tests.[7]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer