Most patients with hyperkalaemia are asymptomatic or have non-specific features only.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Rossignol P, Legrand M, Kosiborod M, et al. Emergency management of severe hyperkalemia: guideline for best practice and opportunities for the future. Pharmacol Res. 2016 Nov;113(pt a):585-91.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.09.039

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27693804?tool=bestpractice.com

However, be aware that some patients with significant hyperkalaemia may present with cardiac arrest, which is not covered in this topic.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Rossignol P, Legrand M, Kosiborod M, et al. Emergency management of severe hyperkalemia: guideline for best practice and opportunities for the future. Pharmacol Res. 2016 Nov;113(pt a):585-91.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.09.039

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27693804?tool=bestpractice.com

See Cardiac arrest.

A thorough history is key for a patient with suspected or confirmed hyperkalaemia in order to check for underlying causes and exclude pseudohyperkalaemia, spurious hyperkalaemia, and cellular redistribution of potassium.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

If hyperkalaemia is suspected, take the following key steps:

Confirm elevation of potassium (potassium ≥5.5 mmol/L (≥5.5 mEq/L]) and severity of hyperkalaemia using serum potassium or blood gas measurement[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Obtain an urgent 12-lead ECG in all hospitalised patients with a serum potassium ≥6.0 mmol/L (≥6.0 mEq/L; or use the threshold in your local protocol) to check for ECG changes that will determine the urgency and type of treatment[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Check for kidney dysfunction and any other underlying causes of hyperkalaemia.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

History

The most common features of hyperkalaemia are weakness and generalised fatigue. Other common features are paraesthesia and muscle cramps. These may progress to flaccid muscle paralysis.[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Occasionally a patient may describe:

Nausea and vomiting[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Diarrhoea[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Shortness of breath

Chest pain

Palpitations.

There may be features of the underlying precipitant of hyperkalaemia such as diarrhoea and vomiting, or infection, which can cause acute kidney injury.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

Elicit any key risk factors for hyperkalaemia.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

Key risk factors include:

Kidney dysfunction (particularly end-stage kidney disease), including people receiving dialysis who are fasting or have missed dialysis[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Rossignol P, Legrand M, Kosiborod M, et al. Emergency management of severe hyperkalemia: guideline for best practice and opportunities for the future. Pharmacol Res. 2016 Nov;113(pt a):585-91.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.09.039

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27693804?tool=bestpractice.com

[13]Chan KE, Thadhani RI, Maddux FW. Adherence barriers to chronic dialysis in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Nov;25(11):2642-8.

https://www.doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2013111160

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24762400?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Allon M, Takeshian A, Shanklin N. Effect of insulin-plus-glucose infusion with or without epinephrine on fasting hyperkalemia. Kidney Int. 1993 Jan;43(1):212-7.

https://www.doi.org/10.1038/ki.1993.34

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8433561?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]Allon M. Hyperkalemia in end-stage renal disease: mechanisms and management. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995 Oct;6(4):1134-42.

https://www.doi.org/10.1681/ASN.V641134

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8589279?tool=bestpractice.com

Use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi), aldosterone antagonists, or trimethoprim[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Bandak G, Sang Y, Gasparini A, et al. Hyperkalemia after initiating renin-angiotensin system blockade: the Stockholm creatinine measurements (SCREAM) project. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017 Jul 19;6(7):e005428.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5586281

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28724651?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Parving HH, Brenner BM, McMurray JJ, et al. Cardiorenal end points in a trial of aliskiren for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012 Dec 6;367(23):2204-13.

https://www.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1208799

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23121378?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, et al. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013 Nov 14;369(20):1892-903.

https://www.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1303154

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24206457?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]ONTARGET Investigators; Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008 Apr 10;358(15):1547-59.

https://www.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0801317

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18378520?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Vukadinović D, Lavall D, Vukadinović AN, et al. True rate of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists-related hyperkalemia in placebo-controlled trials: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2017 Jun;188:99-108.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2017.03.011

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28577687?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Velázquez H, Perazella MA, Wright FS, et al. Renal mechanism of trimethoprim-induced hyperkalemia. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Aug 15;119(4):296-301.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8328738?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2022 May 3;145(18):e895-1032.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35363499?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 11. Chronic kidney disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes - 2022. Diabetes Care. 2022 Jan 1;45(suppl 1):S175-84.

https://www.doi.org/10.2337/dc22-S011

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34964873?tool=bestpractice.com

Heart failure[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Rossignol P, Legrand M, Kosiborod M, et al. Emergency management of severe hyperkalemia: guideline for best practice and opportunities for the future. Pharmacol Res. 2016 Nov;113(pt a):585-91.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.09.039

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27693804?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2022 May 3;145(18):e895-1032.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35363499?tool=bestpractice.com

Liver disease[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

Tissue breakdown (e.g., rhabdomyolysis, trauma, tumour lysis syndrome, and severe hypothermia)[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Sever MS, Erek E, Vanholder R, et al. Serum potassium in the crush syndrome victims of the Marmara disaster. Clin Nephrol. 2003 May;59(5):326-33.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12779093?tool=bestpractice.com

[25]Perkins RM, Aboudara MC, Abbott KC, et al. Resuscitative hyperkalemia in noncrush trauma: a prospective, observational study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 Mar;2(2):313-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.2215/CJN.03070906

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17699430?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]Schaller MD, Fischer AP, Perret CH. Hyperkalemia: a prognostic factor during acute severe hypothermia. JAMA. 1990 Oct 10;264(14):1842-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2402043?tool=bestpractice.com

Distal renal tubule defects that affect potassium excretion.[16]Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Hyperkalemia across the continuum of kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Jan 6;13(1):155-7.

https://www.doi.org/10.2215/CJN.09340817

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29114006?tool=bestpractice.com

Take a careful drug history. Ask about current drugs, any recent changes to drugs, and use of over-the-counter drugs or supplements (such as intake of high doses of potassium supplements).[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

Treatment with RAASi, aldosterone antagonists, or trimethoprim is strongly associated with hyperkalaemia.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Bandak G, Sang Y, Gasparini A, et al. Hyperkalemia after initiating renin-angiotensin system blockade: the Stockholm creatinine measurements (SCREAM) project. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017 Jul 19;6(7):e005428.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5586281

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28724651?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Parving HH, Brenner BM, McMurray JJ, et al. Cardiorenal end points in a trial of aliskiren for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012 Dec 6;367(23):2204-13.

https://www.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1208799

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23121378?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, et al. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013 Nov 14;369(20):1892-903.

https://www.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1303154

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24206457?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]ONTARGET Investigators; Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008 Apr 10;358(15):1547-59.

https://www.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0801317

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18378520?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Vukadinović D, Lavall D, Vukadinović AN, et al. True rate of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists-related hyperkalemia in placebo-controlled trials: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2017 Jun;188:99-108.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2017.03.011

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28577687?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Velázquez H, Perazella MA, Wright FS, et al. Renal mechanism of trimethoprim-induced hyperkalemia. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Aug 15;119(4):296-301.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8328738?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2022 May 3;145(18):e895-1032.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35363499?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 11. Chronic kidney disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes - 2022. Diabetes Care. 2022 Jan 1;45(suppl 1):S175-84.

https://www.doi.org/10.2337/dc22-S011

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34964873?tool=bestpractice.com

However, many other drugs can cause hyperkalaemia, particularly when taken in combination with RAASi or aldosterone antagonists, and if there is concurrent kidney dysfunction. These include, but are not limited to:

Arginine[56]Cremades A, Del Rio-Garcia J, Lambertos A, et al. Tissue-specific regulation of potassium homeostasis by high doses of cationic amino acids. Springerplus. 2016;5:616.

https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2224-3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27330882?tool=bestpractice.com

Azole antifungals (e.g., ketoconazole)[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Beta-blockers (non-cardioselective)[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., ciclosporin, tacrolimus)[4]Clase CM, Carrero JJ, Ellison DH, et al. Potassium homeostasis and management of dyskalemia in kidney diseases: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2020 Jan;97(1):42-61.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.09.018

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31706619?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Hoorn EJ, Walsh SB, McCormick JA, et al. The calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus activates the renal sodium chloride cotransporter to cause hypertension. Nat Med. 2011 Oct 2;17(10):1304-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21963515?tool=bestpractice.com

Digoxin[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Heparin[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Baird DP, Hunter RW, Neary JJ. Hyperkalaemia on the surgical ward. BMJ. 2015 Oct 21;351:h5531.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26489645?tool=bestpractice.com

Isoflurane[4]Clase CM, Carrero JJ, Ellison DH, et al. Potassium homeostasis and management of dyskalemia in kidney diseases: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2020 Jan;97(1):42-61.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.09.018

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31706619?tool=bestpractice.com

Lithium[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Mannitol[57]Fanous AA, Tick RC, Gu EY, et al. Life-threatening mannitol-induced hyperkalemia in neurosurgical patients. World Neurosurg. 2016 Jul;91:672.e5-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2016.04.021

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27086258?tool=bestpractice.com

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Penicillins[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Pentamidine[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Potassium-sparing diuretics (e.g., amiloride, triamterene)[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Somatostatin[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Suxamethonium.[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

In particular, certain drugs (e.g., mannitol, arginine, suxamethonium, digoxin) cause hyperkalaemia due to cellular redistribution. This list is not exhaustive and you should consult your local drug formulary for more information.

Physical examination

In general, there are no specific features on physical examination alone that lead to the diagnosis of hyperkalaemia. However, always be alert to the diagnosis if there is severe bradycardia, which results from heart block. Other features may include:

Extrasystoles and cardiac pauses

Tachypnoea, which is due to respiratory muscle weakness

Skeletal muscle weakness or flaccid muscle paralysis with depressed or absent deep tendon reflexes

Hypoactive or absent bowel sounds if ileus is present.

Initial investigations

Serum potassium

Order serum potassium in all patients.[12]Rossignol P, Legrand M, Kosiborod M, et al. Emergency management of severe hyperkalemia: guideline for best practice and opportunities for the future. Pharmacol Res. 2016 Nov;113(pt a):585-91.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.09.039

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27693804?tool=bestpractice.com

In an emergency setting, measure potassium using arterial or venous blood gas while waiting for the results from formal laboratory measurement.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

There is no universally accepted definition of hyperkalaemia. However, many guidelines use a threshold of serum potassium ≥5.5 mmol/L (≥5.5 mEq/L) and the European Resuscitation Council classification of severity of hyperkalaemia, which is as follows:[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Lott C, Truhlář A, Alfonzo A, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation. 2021 Apr;161:152-219.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.011

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33773826?tool=bestpractice.com

5.5 to 5.9 mmol/L (5.5 to 5.9 mEq/L): mild

6.0 to 6.4 mmol/L (6.0 to 6.4 mEq/L): moderate

≥6.5 mmol/L (≥6.5 mEq/L): severe.

Note that Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) uses a similar scale but also adds ECG changes to categorise severity; according to the KDIGO scale, mild hyperkalaemia with ECG changes increases the severity level to moderate, and moderate hyperkalaemia with ECG changes increases the severity level to severe.[4]Clase CM, Carrero JJ, Ellison DH, et al. Potassium homeostasis and management of dyskalemia in kidney diseases: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2020 Jan;97(1):42-61.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.09.018

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31706619?tool=bestpractice.com

It is useful to know whether serum or plasma was used for potassium measurement. Plasma potassium concentrations are on average usually 0.1 to 0.4 mmol/L (0.1 to 0.4 mEq/L) lower than serum levels due to release of potassium from platelets during coagulation.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

If serum potassium is elevated, exclude pseudohyperkalaemia (due to potassium released from blood cells during in vitro coagulation or errors in sample collection and/or storage) and cellular redistribution of potassium.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

Assess the probability of these by reviewing the medical history (e.g., for diabetes, heart failure, chronic kidney disease), drug history, and other blood results (e.g., full blood count), as well as repeating the serum potassium level.[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

See Differentials.

12-lead ECG

Obtain an urgent 12-lead ECG in all hospitalised patients with a serum potassium level of ≥6.0 mmol/L (≥6 mEq/L; or use the threshold in your local protocol) to assess for changes associated with hyperkalaemia, which can help to determine the urgency and type of treatment required.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

Note that the ECG is often normal in hyperkalaemia.[4]Clase CM, Carrero JJ, Ellison DH, et al. Potassium homeostasis and management of dyskalemia in kidney diseases: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2020 Jan;97(1):42-61.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.09.018

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31706619?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Rossignol P, Legrand M, Kosiborod M, et al. Emergency management of severe hyperkalemia: guideline for best practice and opportunities for the future. Pharmacol Res. 2016 Nov;113(pt a):585-91.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.09.039

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27693804?tool=bestpractice.com

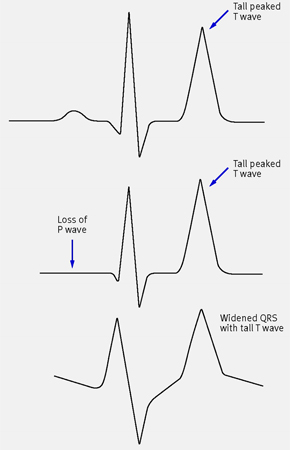

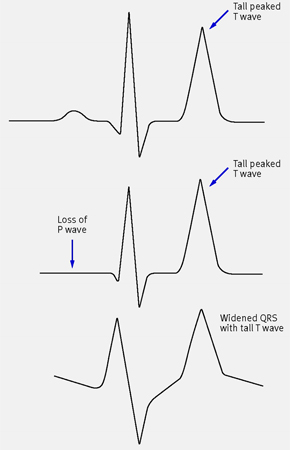

ECG changes may progress from peaked T waves to prolonged PR interval and progressive widening of QRS complex, followed by sine wave patterns, ventricular fibrillation, and asystole.[4]Clase CM, Carrero JJ, Ellison DH, et al. Potassium homeostasis and management of dyskalemia in kidney diseases: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2020 Jan;97(1):42-61.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.09.018

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31706619?tool=bestpractice.com

If hyperkalaemia-related changes are present, they may correlate with the severity and rate of rise of serum potassium.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

However, be aware that ECG changes are dependent on a variety of other factors (e.g., concurrent electrolyte abnormalities, acid-base status, prior cardiac injury), and relying on or expecting progressive ECG changes with increasing severity of hyperkalaemia may be misleading and potentially dangerous.[2]Rafique Z, Peacock F, Armstead T, et al. Hyperkalemia management in the emergency department: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021 Oct;2(5):e12572.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12572

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34632453?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG changes in people with hyperkalaemiaBMJ 2009; 339:b4114. Copyright ©2009 by the BMJ Publishing Group [Citation ends].

Other blood tests

Renal chemistry (includes, in addition to potassium as discussed above, sodium, chloride, bicarbonate, urea, and creatinine): order to check for kidney dysfunction as a cause of hyperkalaemia, and to exclude cellular redistribution of potassium.

Plasma glucose: order to exclude hyperglycaemia, which causes cellular redistribution of potassium. This is useful in patients with known or suspected diabetes and when diabetic ketoacidosis is likely.

Serum calcium: order to check for hypocalcaemia as this will potentiate the toxicity of hyperkalaemia. Calcium will also be low in rhabdomyolysis, which is a cause of hyperkalaemia.

FBC: order (or review a recent FBC) if pseudohyperkalaemia is suspected to exclude a haematological disorder.[1]Alfonzo A, Harrison A, Baines R, et al; UK Kidney Association (formerly the Renal Association). Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults. June 2020 [internet publication].

https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/RENAL%20ASSOCIATION%20HYPERKALAEMIA%20GUIDELINE%20-%20JULY%202022%20V2_0.pdf

Hyperkalaemia in the setting of significantly elevated white cell count or platelet count with no obvious risk factor for hyperkalaemia indicates pseudohyperkalaemia.

Other investigations

Consider other investigations depending on the suspected underlying cause. These include:

Uric acid and phosphorus if tumour lysis syndrome is suspected.

Creatine kinase if rhabdomyolysis is suspected.[64]Poels PJ, Gabreëls FJ. Rhabdomyolysis: a review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1993 Sep;95(3):175-92.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/0303-8467(93)90122-w

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8242960?tool=bestpractice.com

[65]Knochel JP. Rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinuria. Annu Rev Med. 1982;33:435-43.

https://www.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.33.020182.002251

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6282181?tool=bestpractice.com

Serum digoxin level if the patient is taking digoxin or if suicide is known to have been attempted with digoxin ingestion.

Cortisol and aldosterone levels if mineralocorticoid deficiency is suspected (e.g., primary adrenal insufficiency [Addison's disease]) and other potential causes of hyperkalaemia have been excluded. See Primary adrenal insufficiency.

Urine pH if renal tubular acidosis is suspected.[66]Morris RC Jr. Renal tubular acidosis. Mechanisms, classification and implications. N Engl J Med. 1969 Dec 18;281(25):1405-13.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4901460?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]Rodríguez Soriano J. Renal tubular acidosis: the clinical entity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002 Aug;13(8):2160-70.

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/01.asn.0000023430.92674.e5

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12138150?tool=bestpractice.com

[68]Batlle D, Moorthi KM, Schlueter W, et al. Distal renal tubular acidosis and the potassium enigma. Semin Nephrol. 2006 Nov;26(6):471-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17275585?tool=bestpractice.com

See Renal tubular acidosis.

Plasma renin activity if pseudohypoaldosteronism is suspected.

24-hour urine potassium excretion to distinguish renal from extrarenal causes of hyperkalaemia.

Plasma and urine potassium and osmolality to calculate transtubular potassium gradient, if values from 24-hour urine potassium secretion are difficult to interpret or to identify impaired distal tubular secretion of potassium due to hypoaldosteronism or aldosterone resistance.