Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Follow your local protocol to quickly identify and manage patients with suspected acute upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding caused by an MWT.

Acute upper GI bleeding is a medical emergency requiring rapid intervention. In the UK, the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) has produced a consensus care bundle for the early management of acute upper GI bleeding.[31]

Suspect an MWT if the patient presents with small and self-limited episodes of haematemesis and/or melaena, and has a recent history of forceful or recurrent retching, vomiting, coughing, or straining.[1]

Haematemesis may vary from flecks or streaks of blood mixed with gastric contents and/or mucus, blackish or 'coffee grounds', to a bright-red bloody emesis.

Perform a risk assessment. If Glasgow-Blatchford score ≤1, consider managing the patient as an outpatient if safe and appropriate to do so.[31][32]

Refer all patients with suspected acute upper GI bleeding for upper GI endoscopy (i.e., gastroscopy).[31][32][33] Follow your local protocol for recommendations on the optimal timing of the procedure for your patient. Guidelines from the National Institute for Care and Health Excellence (NICE) in the UK and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), and a consensus care bundle led by the BSG, agree that endoscopy should always be performed early (i.e., within 24 hours of presentation) with suspected acute upper GI bleed. However, the exact timing of the procedure within the 24-hour period is controversial and specific recommendations from NICE, the BSG, and the ESGE differ.[31][32][33]

Before diagnostic endoscopy consider intubating the patient if needed (e.g., if there is haematemesis, or there is a perceived risk of a haemodynamically unstable patient having blood in the stomach, or if the patient presents with an altered mental status). Make sure the patient is appropriately resuscitated before undergoing diagnostic endoscopy.

Suspect an MWT (a longitudinal mucosal tear or laceration of the mucous membrane in the region of the gastroesophageal junction and gastric cardia) if the patient presents with small and self-limited episodes of haematemesis and/or melaena, and has a recent history of forceful or recurrent retching, vomiting, coughing, or straining.[1]

Haematemesis may vary from flecks or streaks of blood mixed with gastric contents and/or mucus, blackish or 'coffee grounds', to a bright-red bloody emesis.

Practical tip

Note that 'coffee ground' vomit is subjective. Perform a rectal examination to look for blood or signs of melaena, and calculate the Glasgow-Blatchford Score (GBS). If GBS ≤1, consider managing the patient as an outpatient if safe and appropriate to do so.[31][32] See Risk stratification below.

Follow your local protocol to quickly identify and manage patients with suspected acute upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding caused by MWT. Acute upper GI bleeding is a medical emergency requiring rapid intervention. In the UK, the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) has produced a consensus care bundle for the early management of acute upper GI bleeding.[31]

Bleeding caused by MWT is usually self-limiting but patients with active bleeding (particularly those with comorbidities) may be haemodynamically unstable. See Active non-variceal bleeding: resuscitation and initial management under Management recommendations.

Massive haemorrhage requiring blood transfusion and leading to death has been described in patients with MWT, but this is rare.[4][5][6]

Less common presenting symptoms of MWT include:

Dizziness, light-headedness

Syncope

Dysphagia

Odynophagia

Melaena

Hypotension

Haematochezia

Retrosternal, epigastric, or back pain.

Take a complete medical history to establish any precipitating factors. Be aware, however, that no precipitating factor is found in >40% of patients with MWT.[13]

Ask the patient about:

History of forceful or recurrent retching, vomiting, coughing, or straining

Haematemesis due to MWT usually occurs after a forceful or recurrent retching, vomiting, coughing, or straining

Retrosternal, epigastric, or back pain

Severe pain is unusual in patients with MWT. If the patient describes severe pain, consider whether this might be caused by a tear deeper than the mucous membrane; investigate accordingly. A deeper tear may indicate an intramucosal oesophageal haematoma or transmural oesophageal rupture. Suspect an oesophageal perforation if the patient has retrosternal or epigastric pain alongside interscapular radiation, dyspnoea, cyanosis, and fever

Dysphagia

Particularly in patients aged over 50 years with a new onset of dysphagia, patients who smoke and drink alcohol on a regular basis, patients with a long history of oesophageal reflux, and when it is progressive (for solid food first, then solid and liquids) in a short period of time (weeks or months)

Odynophagia

MWT can cause pain when swallowing food and/or fluids

Dizziness; light-headedness

Can be caused by a sudden drop in blood pressure associated with bleeding.

Ascertain whether the patient has any risk factors for MWT, with a focus on:

Heavy alcohol use

Alcohol use is present in 30% to 60% of patients[1]

Conditions that predispose to retching and vomiting. For example:

Food poisoning, gastroenteritis, or any gastrointestinal condition resulting in obstruction; hepatitis, gallstones, and cholecystitis; hyperemesis gravidarum; urinary tract infection, renal failure, and ureteropelvic obstruction; brain tumours, hydrocephalus, congenital disease, trauma, meningitis, pseudotumour cerebri, migraine headaches, and seizures; anorexia nervosa, bulimia, cyclic vomiting syndrome, toxins, polyethylene glycol lavage, chemotherapy agents, and post-anaesthesia or post-surgery; hiatal hernia and hiccups[6][11][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][27][28]

Chronic cough

May be associated with a number of conditions, including whooping cough, bronchitis, bronchiectasis, emphysema, COPD, or lung cancer[22]

Blunt abdominal trauma and cardiopulmonary resuscitation[29][30]

Mucosal tear or laceration during a routine endoscopy; although rare, this is the most common cause of iatrogenic MWT.[23][24]

Perform a full physical examination. Bear in mind that there are no specific physical signs to watch for in patients with MWT. The physical findings are linked to the underlying disorder causing the vomiting, retching, coughing, and/or straining.

Perform a rectal examination to check for signs of melaena or haematochezia.

Suspect upper gastrointestinal bleeding in any patient presenting with melaena.

Blood loss may be considerable in some patients with MWT. However, bleeding is self-limiting in 80% to 90% of patients and haematochezia is rare.[2] Haematochezia in MWT may occur if there is an actively bleeding lesion in which the rapidity of transit precludes any digestion of blood. Haemodynamically unstable patients with haematochezia and other historical factors suggesting upper gastrointestinal bleeding require urgent investigation and treatment. See Management recommendations.

Check for signs of internal bleeding such as:

Tachycardia

Postural or orthostatic hypotension

Seen in up to 45% of adults with MWT[13]

Dizziness, light-headedness

Due to a sudden drop in blood pressure caused by bleeding

Shock

Haemorrhage in MWT is self-limiting in 80% to 90% of patients.[2] Suspect a more serious underlying pathology, such as oesophageal varices, Dieulafoy's lesion, actively bleeding peptic ulcer disease, or aortoenteric fistula in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding and shock. See Differential diagnosis.

On presentation or admission, perform urgent observations on the patient with suspected acute upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding using a validated early warning score. A consensus care bundle for acute upper GI bleeding led by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) recommends the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) for patients with suspected acute upper GI bleeding.[31] Use NEWS2, or a similarly validated early warning score, to help determine how quickly the patient needs an endoscopy. NEWS2 Opens in new window

Use prognostic risk assessment scores, as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK, the BSG consensus care bundle, and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), in all patients with acute upper GI bleeding.[31][32][33] Use the scores to help decide which patients need urgent endoscopy (within the next 12 hours), which patients are stable enough to be admitted and have non-urgent endoscopy (within 24 hours), and which patients can be discharged from hospital.[34][35]

Use the Glasgow-Blatchford score at first assessment to identify patients with low-risk bleeds who can be safely discharged without undergoing endoscopy.[31][32][33] [ Blatchford Score for Gastrointestinal Bleeding Opens in new window ]

If Glasgow-Blatchford score ≤1, consider managing the patient as an outpatient if safe and appropriate to do so. This approach is supported by latest evidence and in line with recommendations from the BSG and ESGE.[31][32]

Evidence shows that a Glasgow-Blatchford score ≤1 identifies a significantly higher proportion of low-risk patients compared with a Glasgow-Blatchford score of 0.[36][37]

Bear in mind that discharge recommendations from NICE (early discharge for patients with a pre-endoscopy Blatchford score of 0) are based on older evidence and therefore do not reflect current practice.[33]

Use the full Rockall score after endoscopy as recommended by NICE.[33] [ Rockall Score for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Opens in new window ]

A score of ≤2 is associated with a low risk of further bleeding or death.

Refer all patients with suspected acute upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding for upper GI endoscopy (i.e., gastroscopy).[31][32][33] Follow your local protocol for recommendations on the optimal timing of the procedure for your patient. Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), and a consensus care bundle led by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG), agree that endoscopy should always be performed early (i.e., within 24 hours of presentation) with suspected acute upper GI bleed. However, the exact timing of the procedure within the 24-hour period is controversial and specific recommendations from NICE, the BSG, and the ESGE differ as follows.

The ESGE recommends early (≤24 hours from presentation) upper GI endoscopy following haemodynamic resuscitation. The ESGE does not recommend urgent (defined by the ESGE as ≤12 hours from presentation) endoscopy.[32]

NICE and the BSG care bundle recommend:[31][33]

Urgent endoscopy, immediately after resuscitation, if the patient is unstable with severe acute upper GI bleeding

Endoscopy within 24 hours of admission for all other patients with upper GI bleeding.

In the absence of data on urgent endoscopy for unstable and high-risk patients, the NICE guideline development group (GDG) based their recommendation for urgent endoscopy on consensus expert opinion of the GDG.[33] The BSG consensus care bundle acknowledges that endoscopy performed <12 hours after presentation in patients with acute non-variceal upper GI bleeding is controversial, and notes that several studies associate endoscopy performed <12 hours after presentation with adverse outcomes.[31][38][39][40][41] The ESGE also recognises that the evidence in the area is conflicting; the ESGE bases their recommendation on studies showing that urgent (defined by the ESGE as ≤12 hours from presentation) endoscopy is associated with worse patient outcomes or with no improvement in clinical outcomes compared with non-urgent early endoscopy.[40][42][43]

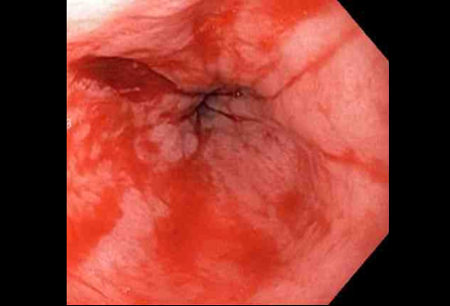

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Actively bleeding tear appears as a red longitudinal defect with normal surrounding mucosaFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends].

Gastroscopy is the test of choice for diagnosis and treatment.[32][33]

An MWT is usually seen at or below the gastro-oesophageal junction as a single linear defect, with normal surrounding mucosa.

An MWT typically varies in length from a few millimetres to several centimetres.

Co-existing lesions are common and may contribute to the bleeding process (e.g., peptic ulcer, erosive oesophagitis).

Practical tip

The tear is often, but not always, seen between 2 o’ clock and 6 o'clock at or below the gastro-oesophageal junction.

More info: Contraindications for upper GI endoscopy

Absolute contraindications for upper endoscopy include:

Severe hypotension/shock

Acute perforation

Acute myocardial infarction

Peritonitis.

Relative contraindications for upper endoscopy include:

Uncooperative patient

Coma (except those already intubated)

Cardiac arrhythmias

Myocardial ischaemia (recent event).

Consider a chest x-ray in patients suspected of having a complication such as an oesophageal perforation.[29] Consider an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan in patients with suspected peritonitis or perforation.

Consider a CT angiogram in patients with refractory bleeding requiring arterial embolisation. Use the CT angiogram to localise the bleeding site and define the arterial anatomy.

Request a full blood count, electrolytes, haematocrit, platelets, urea and creatinine, and liver function tests.

These are important in evaluating the severity of the bleeding and to monitor patients.

Send blood for typing and cross-matching.

Patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding can experience rapid clinical deterioration. Blood products may become necessary.

Candidates for blood transfusion include patients with anaemia at presentation or those with ongoing bleeding.

Order prothrombin time/international normalised ratio and activated partial thromboplastin time in all patients on anticoagulants or in those suspected of coagulopathy.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer