Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Assess the patient using the Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach.[31] Involve the multidisciplinary team (including thoracic or general surgeons, orthopaedic and orthogeriatric input if the patient is older and/or frail, and anaesthetists for pain management).

Treat pain immediately and reassess regularly.[36] Ensure a range of analgesia is available, including regional nerve blocks (e.g., serratus anterior or erector spinae blocks) or thoracic epidural anaesthesia, and use an agreed analgesia protocol.[36][39]

Managing pain improves pulmonary function; decreases the risk of pulmonary complications such as atelectasis, poor oxygenation, and respiratory compromise; and can prevent respiratory failure.[39]

Refer unstable patients to critical care for further treatment and mechanical ventilation.

Seek advice early on with the appropriate specialist if the patient has complications, such as pneumothorax, haemopneumothorax, pulmonary contusions, pneumonia, and flail chest, or associated injuries, such as significant head injury or intra-abdominal organ injury.

Older patients and those with >2 rib fractures are at a higher risk of pulmonary complications.

Surgical stabilisation in patients with flail chest should be considered by specialists on a case-by-case basis.[46][47]

Arrange chest physiotherapy and encourage mobility to improve mucus and secretion clearance.[36][48]

Consider the underlying cause, such as malignancy, osteoporosis, or non-accidental injury.

In patients with major chest trauma, the main treatment goals are to:[32]

Control pain

Protect the underlying lung

Maintain adequate ventilation and oxygenation

Prevent infection.

Once associated injuries have been assessed and managed the aims are pain management, prevention of complications, and rehabilitation.

Management of the patient with rib fractures will depend on the patient’s age, the number of ribs fractured, and concomitant injuries. A patient with multiple injuries should be evaluated by the appropriate specialists.

In a patient with blunt chest wall trauma, management should be directed by a consultant-led trauma team.

The most important aspects of management are multimodal analgesia and ventilatory support (see below).[32]

A displaced fracture may cause a pleural tear, or there may be distortion to the thorax or deformity of the chest wall, all of which may have an adverse effect on ventilation.

Pain from the fracture may limit chest wall movement, leading to reduced tidal volumes, or an inability to cough.[32]

Admit patients with respiratory compromise for pain control, mucus and secretion clearance, deep breathing, early mobilisation, and observation.[27][36][48] Transfer to a centre that has either a pulmonary critical care or trauma team because of the increased morbidity and mortality in this patient group.

Many rib fractures are to a single rib and are of low severity, requiring minimal intervention from medical teams. Use a pain score and monitor it regularly, along with a validated scoring system for assessing acute deterioration, such as the National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2).[39] Use pain control, physiotherapy, and mobilisation to manage single rib fractures without associated injuries. It is important to remember than even single rib fractures can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in frail, elderly patients.[49]

Treat stress fractures, which often occur in athletes, with periods of rest, analgesia, and activity modification until symptoms resolve.[50]

There are scoring systems used to stratify patients and determine treatment. These are often based on the patient’s age and the number of fractures; however, there is no single universally accepted system.[32]

Analgesia

Treat the patient’s pain immediately and reassess regularly.[36] Managing pain is imperative as it improves pulmonary function; decreases the risk of pulmonary complications such as atelectasis, poor oxygenation, and respiratory compromise; and can prevent respiratory failure.[39]

Individualise analgesia based on the patient’s age, their level of pain, and the extent of the injury.[39][51]

Ensure a range of analgesia is available, including regional nerve blocks (e.g., serratus anterior or erector spinae blocks) or thoracic epidural anaesthesia, and use an agreed analgesia protocol.[36][39]

Start oral analgesics, such as paracetamol or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID).[32]

Consider titrated intravenous morphine initially, with a range of follow-up regimens including paracetamol, an NSAID, and an oral opioid, or patient-controlled analgesia, or referral to anaesthetics for epidural anaesthesia or a nerve block.[32][39]

There are many options for regional anaesthesia, which can be tailored to the patient.[32]

Consider transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for pain management of uncomplicated rib fractures.

TENS was found in a randomised controlled trial to be more effective than NSAIDs for relieving pain in patients with minor rib fractures following blunt chest trauma.[52]

Ventilatory support

Provide supplementary oxygen to treat hypoxia.[32] Use high-flow nasal cannulae or non-invasive ventilation for patients with significant hypoxia, with or without hypercarbia.[32][53]

Refer unstable patients to critical care for further treatment and mechanical ventilation.[53] Severity of the injuries may indicate invasive ventilation is required.[32] Isolated rib fractures rarely require mechanical ventilation unless associated with other injuries, such as pulmonary contusion.[54]

For patients with flail chest, mechanical ventilation is needed only if they present with shock, head injury, severe pulmonary dysfunction, or deteriorating respiratory status, or if surgery is required immediately.[54]

Consider internal fixation of ribs or flail chest in patients who fail to wean from the ventilator, or when thoracotomy is required for other reasons.[55]

Systematic reviews have reported an association between operative management of rib fractures in flail chest and reduced ventilator requirements, as well as earlier discharge from intensive care.[56][57][58] This effect may be less in the presence of pulmonary contusion.[56]

Respiratory hygiene

Deep breathing exercises assessed with incentive spirometry and assisted coughing may help prevent complications.[32][36][48][53]

Chest physiotherapy and mobilisation

Arrange chest physiotherapy and encourage mobility to improve mucus and secretion clearance.[36][48]

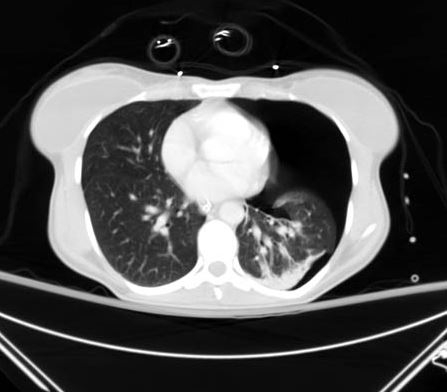

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing large left-sided pneumothoraxFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR depicting the same pneumothorax as shown on CTFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR depicting the same pneumothorax as shown on CTFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

Management of complications

Seek advice early on with the appropriate specialist if the patient has complications, such as pneumothorax, haemopneumothorax, pulmonary contusions, pneumonia, and flail chest, or associated injuries, such as significant head injury or intra-abdominal organ injury.

Rib fractures can impair adequate ventilation, resulting in atelectasis, poor oxygenation, and respiratory compromise. Impaired oxygenation can be due to impaired chest wall movement following chest wall pain or be indicative of underlying pneumothorax, haemothorax, or pulmonary contusion.

Pneumothorax occurs in about 14% to 37% of rib fractures, haemopneumothorax in 20% to 27%, pulmonary contusions in 17%, and a flail chest in up to 6%.[8][9][10] Traumatic injuries to the first rib have a 3% risk of concomitant great-vessel injury.[23]

A flail segment, fracture of the sternum or scapula, multiple displaced rib fractures, and fractures of ribs 1 to 3 all suggest a significant amount of force has been transmitted across the thorax, which increases the likelihood of associated injuries and damage to major intrathoracic structures.[32]

See Complications.

Surgical stabilisation of rib fractures is not required in most patients with simple rib fractures. However, it may be indicated in patients with multiple severely displaced rib fractures (flail chest).[46][47]

Consider surgical stabilisation in patients with flail chest on a case-by-case basis.[46][47] Suitable patients should be selected by critical care specialists, chest physicians, and thoracic surgeons with appropriate training and experience.[47]

Indications for considering surgical stabilisation include:[32]

Severe chest wall injuries, including flail chests

Injuries causing respiratory compromise

Pain control cannot be achieved

Weaning from the ventilator has failed in an intubated patient

The patient is undergoing a thoracotomy for an associated thoracic injury.

A co-existing injury that causes a prolonged period of mechanical ventilation to be necessary is a contraindication to surgical stabilisation.[32]

There is a lack of evidence on the timing of surgery and the methods used.[32]

More information: surgical stabilisation

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence states that evidence on insertion of metal rib reinforcements to stabilise a flail chest wall is limited but consistently shows efficacy, and that there are no safety concerns in the context of patients who have had severe trauma with impaired pulmonary function.[47]

Surgical stabilisation is associated with reductions in:[47][58][59][60]

Number of days spent on mechanical ventilation

Length of hospital stay

Length of intensive care stay

Rate of pneumonia

Need for tracheostomy

Degree of chest wall deformity

Cost of treatment.

A small randomised trial has shown better rates of return to employment following surgical fixation compared with non-operative management.[61]

A Bayesian meta-analysis of 18,018 patients across 39 studies found that surgical stabilisation of rib fracture was associated with lower pulmonary complications and mortality for adults with traumatic rib fractures, compared with non-operative management.[62]

However, any effect on mortality remains uncertain.[58] In addition, the quality of the evidence upon which these recommendations are based is relatively poor.[46]

The procedure should be undertaken by surgeons and anaesthetists experienced in the management of chest injuries and fracture surgery.

Postoperative care should be on a specialist thoracic surgery ward, if not critical care, with continued input from specialist nursing, physiotherapy, pain management, and surgical teams.

Surgical stabilisation of fractures is now included within standard treatment and requires ongoing trials in expert centres.

Refer patients with rib fracture due to underlying primary bone tumours or metastases to the appropriate specialist.

Metastasis from lung, prostate, breast, and liver cancer can involve the ribs, accounting for 12.6% of metastatic lesions.[15] Furthermore, there are numerous primary bone tumours that can present as pathological rib fractures, including osteochondroma, enchondroma, plasmacytoma, chondrosarcoma, and osteosarcoma. About 37% of these lesions are malignant.[16] These should be managed with appropriate specialist referral and treatment.

Identify and treat patients with osteoporosis. See Osteoporosis. As age increases, the absolute risk of sustaining a fragility fracture is inversely proportional to the patient's bone mineral density, with about 27% of these fractures occurring in the ribs.[4]

Consider the causes of falls in older adults. These may be inter-related and multifactorial. See Assessment of falls in the elderly.

Non-accidental injury

Suspect child maltreatment if a child has 1 or more fractures in the absence of a medical condition that predisposes to fragile bones and without a suitable explanation for the injury.[36][37] Follow your local safeguarding protocol or consult with child protective services. See Child abuse.

The presence of rib fractures without associated trauma has the highest probability of being attributed to non-accidental injury when compared with all other fractures.[14]

Among infants aged younger than 12 months presenting with rib fractures, as many as 82% sustained these injuries non-accidentally (i.e., through physical abuse).[2][3] Consult with child protective services for children with suspected physical abuse.

Remember to consider an assessment for vulnerable adults, such as those with dementia, after a traumatic injury. Take into account known or suspected non-accidental injury.[36] Follow local safeguarding protocol if you have any concerns.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer