Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Assess the patient using the Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach.[31] Involve the multidisciplinary team (including thoracic or general surgeons, orthopaedic and orthogeriatric input if the patient is older and/or frail, and anaesthetists for pain management).

Check for other injuries, including significant head injury and intra-abdominal organ injury. Arrange imaging as appropriate and inform the appropriate subspecialty team. See Assessment of acute traumatic brain injury and Assessment of abdominal trauma in adults.

Consider complications, such as pneumothorax (occurs in 14% to 37% of rib fractures), haemopneumothorax (20% to 27% of rib fractures), pulmonary contusions (around 17% of rib fractures), pneumonia (around 33% of patients aged over 65 years with rib fractures), and flail chest (around 6% of rib fractures) and refer to critical care and for surgical input as necessary.[8][9][10][32] See Pneumothorax and Overview of pneumonia.

Establish the cause, if possible.

Risk factors for sustaining rib fractures include blunt chest wall trauma (e.g., from motor vehicle accidents, falls, and industrial accidents), physical abuse, osteoporosis, secondary to cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and participation in sport.[4][6][12][13][30]

Assess the patient’s pain regularly using a pain scale suitable for the person's age, developmental stage, and cognitive function.[33][34][35][36]

Request imaging urgently.

Consider immediate erect chest x‑ray and/or extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (eFAST) to assess chest trauma in adults with severe respiratory compromise.[33]

Consider immediate computed tomography (CT) for adults with suspected chest trauma who can be adequately stabilised for safe transfer to the scanner.[33]

Consider chest x‑ray and/or ultrasound to assess chest trauma in children aged under 16 years. Do not routinely use CT to assess chest trauma in children.[33]

Suspect child maltreatment if a child has 1 or more fractures in the absence of a medical condition that predisposes to fragile bones and without a suitable explanation for the injury.[36][37] Follow your local safeguarding protocol or consult with child protection services. See Child abuse.

Patients typically present with a history of recent blunt thoracic trauma and pain at the site. Involve the multidisciplinary team (including thoracic or general surgeons, orthopaedic and orthogeriatric input if the patient is older and/or frail, and anaesthetists for pain management).

Consider complications, such as pneumothorax (occurs in 14% to 37% of rib fractures), haemopneumothorax (20% to 27% of rib fractures), pulmonary contusions (17% of rib fractures), pneumonia (around 33% of patients aged over 65 years with rib fractures), and flail chest (around 6% of rib fractures) and refer to critical care and for surgical input as necessary.[8][9][10][32] See Pneumothorax and Overview of pneumonia.

Establish the cause, if possible.

Risk factors for sustaining rib fractures include blunt chest wall trauma (e.g., from motor vehicle accidents, falls, and industrial accidents), physical abuse, osteoporosis, secondary to cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and participation in sport.[4][6][12][13][30]

In England, patients presenting with blunt chest wall trauma should be managed within a major trauma network, which may involve transfer to a trauma centre.[33]

Children and infants

Suspect child maltreatment if a child has 1 or more fractures in the absence of a medical condition that predisposes to fragile bones and without a suitable explanation for the injury.[36][37] Follow your local safeguarding protocol or consult with child protection services. See Child abuse.

Among infants aged younger than 12 months presenting with rib fractures, as many as 82% sustained these injuries non-accidentally.[2][3] Of all skeletal injuries, rib fractures have the highest likelihood of being the result of physical abuse.[14]

Practical tip

Checklist for injury in children

Is there an explanation for the injury?

Is the explanation compatible with the injury and the developmental stage of the child?

Is it consistent with the history given?

Has there been a delay in seeking help?

Is the parent’s or carer’s response unusual in any way?

Medical

Ask about pain.

Try to establish the cause.

Rib fractures are most commonly due to blunt chest wall trauma as a result of motor vehicle accidents, falls, physical assaults, and industrial accidents.[8]

Ask the patient or the emergency medical service personnel for information regarding the likely aetiology, such as blunt trauma in a car accident. Significant intrusion of the steering column can apply dramatic force to the thoracic cage.

Consider stress fractures to the ribs in people participating in sport involving repetitive activities, such as baseball, rowing, and golf.[21][22] Diagnosis is suggested by absence of trauma and continued pain.

Ask about osteoporosis.

Ask about malignancy.

Social

Consider the risks in a patient aged over 65/under 12 months.

Ask about the patient’s cigarette smoking history.

Ask about recurrent falls.

Ask about recent or regular alcohol consumption as it can increase the risk of falls and osteoporosis.

Establish usual mobility and activity levels.

Consider stress fractures in people participating in sport.

Ask about the patient’s social circumstances: for example, do they live independently or have a carer?

Complete a safeguarding assessment for vulnerable adults, such as those with dementia, after a traumatic injury. Take into account known or suspected non-accidental injury.[36]

Medication

Consider medications that may need to be reviewed or reversed prior to surgery, such as anticoagulants or oral hypoglycaemics and/or short-acting insulin.

Ask about drugs that increase the risk of fracture, such as drugs that affect bone mineral density, or increase the risk of falls, such as sedatives or antihypertensives.

Family

Ask whether there is a family history of fractures or osteoporosis.

Collateral

Ask about the mechanism of any fall or trauma, if known, and whether there was a loss of consciousness.

A relative or witness may give different answers to the patient.

Establish the patient’s baseline level of functioning:

How does the patient usually manage at home?

How independently can they walk, get undressed, or go to the toilet?

Is there any cognitive impairment?

Assess the patient using the Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach.[31]

Inspect the chest wall and abdomen to look for evidence of:

Chest wall bruising

Look for the ‘seat belt sign’ (bruising across the anterior chest wall); this may not be present acutely

A flail segment and paradoxical breathing, which characterises a flail chest

A flail chest results when multiple ipsilateral ribs are fractured in two or more places, resulting in an unstable segment of the chest wall. Flail chest is often accompanied by other injuries, and carries an increased risk of life-threatening pneumothorax, pulmonary contusion, and haemothorax, with an overall mortality of at least 5%[38]

Other chest wall deformities

Tachypnoea.

Examine the neck veins. Distended neck veins suggest a tension pneumothorax.

Assess tracheal position. The trachea deviates:

Away from tension pneumothorax and large pleural effusions

Towards lobar collapse.

Observe the patient’s colour and capillary refill time.

Palpate the chest for areas of tenderness or surgical emphysema (suggestive of an underlying pneumothorax).

Auscultate to assess whether there is normal air entry bilaterally. Reduced air entry indicates a pneumothorax or haemopneumothorax.

Percuss the patient’s lung fields: hyperresonance is suggestive of a pneumothorax and dullness is suggestive of a haemopneumothorax.

Monitor blood pressure and respiratory rate, looking for signs of tension pneumothorax or cardiac injury. See Pneumothorax and Assessment of chest pain.

Record the patient’s level of consciousness using AVPU (Alert, responds to Voice, responds to Pain, Unresponsive') or the Glasgow Coma Scale score. [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

Look for signs of general respiratory compromise, which can be caused by rib fractures.[39] Older patients and those with >3 rib fractures are at a higher risk of pulmonary complications such as atelectasis, poor oxygenation, and respiratory compromise.

Check for other injuries, including significant head injury and intra-abdominal organ injury (look for abdominal bruising and the ‘seatbelt sign’). Follow a thorough trauma examination process and examine all limbs for injury. See Assessment of acute traumatic brain injury and Assessment of abdominal trauma in adults.

Rib fractures are an indicator of severe trauma. The presence of multiple rib fractures correlates with an increased incidence of solid organ injury (about 35%).[40] Traumatic injuries to the first rib have a 3% risk of concomitant great-vessel injury.[23]

Practical tip

Do not dismiss chest wall injuries in older patients. Patients aged over 65 years have twice the morbidity and mortality compared with younger people; for every increase in the number of ribs fractured, mortality increases by 19% while the risk of pneumonia increases by 27%.[41]

Identify any complications that require urgent treatment, such as pneumothorax, haemopneumothorax, pulmonary contusions, pneumonia, and flail chest. See the Complications section and Pneumothorax and Overview of pneumonia.

Pneumothorax occurs in about 14% to 37% of rib fractures, haemopneumothorax in 20% to 27%, pulmonary contusions in 17%, and a flail chest in up to 6%.[8][9][10] Pneumonia occurs in around one third of patients aged over 65 years with rib fractures.[32]

Ensure there is sufficient analgesia for examination and investigations (see Management or analgesia recommendations).

Assess pain regularly using a pain scale suitable for the person's age, developmental stage, and cognitive function.[32][34][35][36]

Pain and dyspnoea are common. Chest wall pain reduces ventilation by impairing chest wall movement.

Older patients and those with cognitive deficits may perceive pain differently or be less able to communicate their response to it.[32]

Monitor oxygen saturation.[32]

Impaired oxygenation can also be indicative of underlying pneumothorax, haemothorax, or pulmonary contusion.

Rib fractures impair adequate ventilation, resulting in atelectasis, poor oxygenation, and respiratory compromise.

Perform an arterial blood gas for patients with low oxygen saturations.

Take bloods for routine tests, including full blood count and urea and electrolytes. Perform a coagulation screen if the patient is on oral anticoagulants.

Order blood type and cross-match for major trauma patients requiring surgery.

Request imaging urgently in patients with chest trauma as follows:[33]

Consider immediate erect chest x‑ray to assess chest trauma in adults with severe respiratory compromise

Consider immediate computed tomography (CT) for adults with suspected chest trauma who can be adequately stabilised for safe transfer to the scanner

In children aged under 16 years consider chest x‑ray and/or ultrasound first-line

Do not routinely use CT for first‑line imaging to assess chest trauma in children.

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends immediate extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (eFAST) in addition to or instead of chest x-ray in adults with severe respiratory compromise.[33] In practice, the role of point-of-care ultrasonography may be in the immediate assessment of a trauma patient; it is quick and easily performed at the bedside, and can be performed alongside resuscitation.[42] However, it is operator dependent, and more research is needed to confirm its accuracy in diagnosing thoracic trauma.[42]

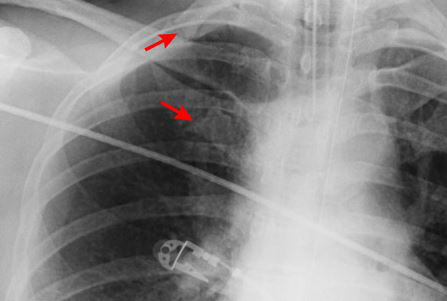

Chest x-ray

Consider immediate erect chest x-ray to assess chest trauma in adults with severe respiratory compromise.[33]

Chest radiography is a first-line imaging modality in any patient presenting with known trauma.[43]

It helps detect the rib fracture, but conventional chest x-rays can miss up to 50% of rib fractures.[44]

It is not usually necessary to perform dedicated rib radiography, in addition to chest radiography, for the diagnosis of rib fractures in adults after minor trauma.[43]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR showing right first rib fractureFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR showing multiple posterior left-sided rib fracturesFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Anteroposterior CXR multiple left-sided rib fractures with chest tube in placeFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Anteroposterior CXR multiple left-sided rib fractures with chest tube in placeFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

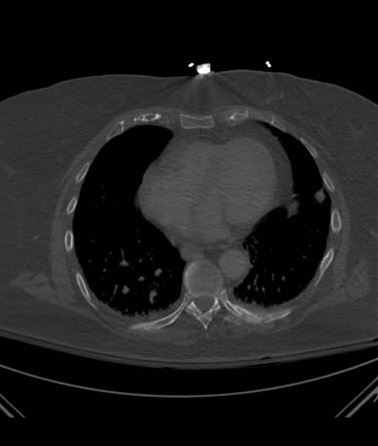

Also assess for pneumothorax, haemothorax, and aortic injury.

Practical tip

In practice, a single rib fracture with a clear history, such as a following a fall, might be made as a clinical diagnosis, even if no fracture is identified on a chest x-ray.

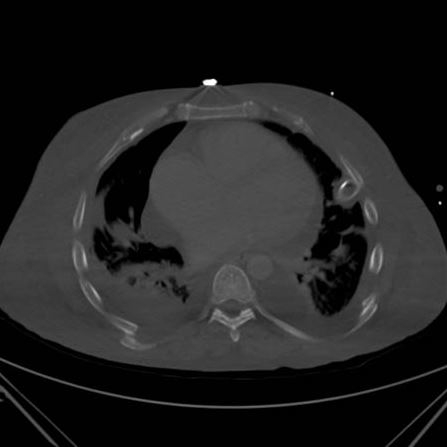

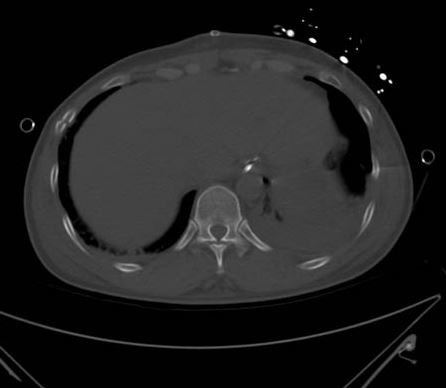

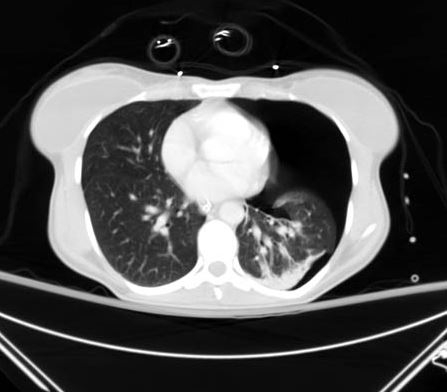

Computed tomography

Use an early CT scan with contrast in adults presenting with blunt chest wall trauma and for adults with suspected chest trauma without severe respiratory compromise who are responding to resuscitation or whose haemodynamic status is normal.[33] In practice, most patients can be stabilised sufficiently in order to receive a CT scan.

CT scan of the chest can improve the sensitivity in detecting rib fractures as well as other injuries.

Consider it if there are clinical features suggestive of rib fracture and there is the potential for improved patient care if rib fracture(s) are detected.

CT imparts significant radiation exposure to the patient and in a patient with minor trauma the increased sensitivity of CT does not necessarily alter management or clinical outcomes of patients who do not have associated injuries.[43]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing bilateral posterior rib fracturesFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT showing right anterolateral rib fractureFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT showing right anterolateral rib fractureFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT showing left posterior segmental rib fractureFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT showing left posterior segmental rib fractureFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing large left-sided pneumothoraxFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing large left-sided pneumothoraxFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR depicting the same pneumothorax as shown on CTFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR depicting the same pneumothorax as shown on CTFrom the collection of Dr Paul Novakovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

In a stable patient who has sustained a high-energy impact trauma, request a CT scan of the head, cervical spine, chest, abdomen, and pelvis to be performed in adults to rule out other injuries.

Do not routinely use CT for first‑line imaging to assess chest trauma in children.[33]

Other imaging

Consider immediate eFAST to assess chest trauma in adults with severe respiratory compromise.[33] In practice, this is likely to be if CT is unavailable.

Consider echocardiography in patients with a clinical or radiological suspicion of cardiac injury. It may reveal cardiac contusion, pericardial tamponade, or acute valvular injury, as a consequence of the fracture.

Skeletal survey in children and infants

Children with suspected maltreatment or non-accidental injury should be investigated according to local safeguarding policies.[36] This would include a skeletal survey in children aged under 2 years (and on a case-by-case basis in older children) and a CT head scan in children aged under 1 year or if there is external evidence of head trauma and/or abnormal neurological symptoms or signs.[45] This imaging should be requested by a senior clinician (usually a paediatrician).[45]

Consider urgent imaging that might be required for other injuries, such as CT of the head and neck.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer