Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Suspect DVT based on the patient’s clinical presentation, and any risk factors for DVT.

Symptoms and signs of DVT are usually unilateral, and include:

Calf swelling (or, more rarely, swelling of the entire leg)

Localised pain along the deep venous system

Oedema

Dilated superficial veins over the foot and leg

Redness and warmth

Coolness

Blue discoloration (cyanosis).

Significant risk factors include:

Recently bedridden for 3 days or more, or major surgery within 12 weeks requiring general or regional anaesthesia[12][26]

Active cancer (treatment ongoing, within 6 months, or palliative)[12][24][25][26]

Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilisation of the lower extremities[12][18][26]

Hereditary thrombophilia (e.g., factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene G20210A mutation, protein C or protein S deficiency)

Presence of medical comorbidities

Certain drugs (e.g., oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives).

If you suspect phlegmasia cerulea dolens (marked swelling, significant pain, and cyanosis) start immediate treatment; do not wait for the results of investigations because this is a life- and limb-threatening emergency.[81] See Phlegmasia cerulea dolens under Management recommendations.

Assess the pretest probability of DVT using the 2-level Wells score (unless the patient is pregnant) to categorise the patient as ‘DVT likely’ (Wells score ≥2) or ‘DVT unlikely’ (Wells score <2).[12][26][27] Use the Wells score in combination with a diagnostic algorithm.[12][26][27] The National Health Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) recommends the following:[12]

If the patient is categorised as ‘DVT likely', organise a venous ultrasound, with the result available within 4 hours.[12][60] Start therapeutic anticoagulation if DVT is confirmed[12]

If the patient is categorised as ‘DVT unlikely’, order a D-dimer with the result available within 4 hours.[12]

Venous ultrasound is the first choice of imaging.[12][26][27] In the UK, different centres may use either proximal or whole-leg venous ultrasound. Check your local protocol to determine the recommended strategy. Consider using computed tomography (or magnetic resonance imaging) venography if venous ultrasound is not available or inconclusive (unless the patient is pregnant).[26][27]

Be aware that diagnosis of DVT is difficult in pregnancy; do not use the Wells score or D-dimer level to diagnose or exclude DVT in these patients.[26] Consider the diagnosis of DVT in a pregnant patient based on a high index of clinical suspicion and ensure close follow-up if DVT is confirmed.[26]

Confirm the diagnosis of DVT if imaging shows a blood clot in a deep vein in the leg, pelvis, or vena cava.[12][26][27]

Use a diagnostic algorithm to evaluate a patient with suspected DVT.

Algorithm for the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis Opens in new window

Symptoms of DVT are usually unilateral, and include:

Calf swelling (or, more rarely, swelling of the entire leg)

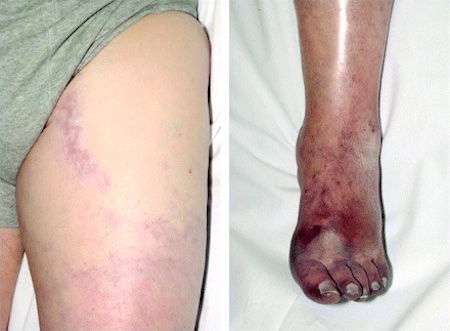

Significant swelling, particularly in combination with severe pain and cyanosis, is a symptom of phlegmasia cerulea dolens (PCD). PCD is a rare life-threatening complication that may lead to arterial ischaemia and can ultimately cause gangrene with high amputation and mortality rates.[81][82] If you suspect PCD, start immediate treatment and refer the patient to a vascular surgeon.[26][82] This is a life- and limb-threatening emergency; do not wait for the results of investigations to start treatment.[26][82] See Phlegmasia cerulea dolens under Management recommendations

Localised pain along the deep venous system

Pain is typically throbbing in nature, and comes on while walking or weight bearing[83]

Oedema

Dilated superficial veins over the foot and leg

Coolness

Redness and warmth[83]

Blue discoloration (cyanosis)

This is also a symptom of PCD.

Symptoms range from severe to very subtle, and patients can be asymptomatic.

Ask about significant risk factors, which include:

Recently bedridden for 3 days or more, or major surgery within 12 weeks requiring general or regional anaesthesia[12][26]

Active cancer (treatment ongoing, within 6 months, or palliative)[12][24][25][26][27]

Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilisation of the lower extremities[12][18][26][27]

Hereditary thrombophilia (e.g., factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene G20210A mutation, protein C or protein S deficiency)

Presence of medical comorbidities

Certain drugs (e.g., oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives).

Always ask about symptoms of concomitant pulmonary embolism.[26][27] See our topic Pulmonary embolism.

Assess unilateral leg swelling by measuring the circumference of the symptomatic leg 10 cm below the tibial tuberosity; compare this with the asymptomatic leg. Any difference between the symptomatic and asymptomatic leg increases the probability of DVT, and a difference of >3 cm between the extremities further increases the probability; these are also elements of the Wells score - see Assessment of pretest probability (Wells score) below.[12][26][27]

Examine the patient for:

Oedema and dilated collateral superficial veins on the affected side

Tenderness along the path of the deep veins (posterior calf compression, compression of the popliteal fossa, and compression along the inner anterior thigh from the groin to the adductor canal)

Coolness

Redness and warmth

Phlegmasia cerulea dolens (PCD); characterised by marked swelling, significant pain, and cyanosis.[81] PCD is a rare life-threatening complication that may lead to arterial ischaemia and can ultimately cause gangrene with high amputation and mortality rates.[81][82] If you suspect PCD, start immediate treatment and refer the patient to a vascular surgeon.[26][82] This is a life- and limb-threatening emergency; do not wait for the results of investigations to start treatment.[26][82] See Phlegmasia cerulea dolens under Management recommendations.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Phlegmasia cerulea dolens: swelling of the left leg and bluish discoloration of the footCooper RM, et al. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens, a rare complication of deep vein thrombosis. Emerg Med J. 2008 Jun;25(6):334 [Citation ends].

Always consider other causes for the patient’s presentation, including (see the Differentials section for more information):[84]

Large or ruptured popliteal cyst (Baker's cyst)

Cellulitis

Musculoskeletal trauma or injury (calf bleeding or haematoma, ruptured Achilles' tendon, or ruptured plantaris tendon).

Practical tip

Bear in mind that DVT may also co-exist with other conditions, particularly cellulitis or a musculoskeletal injury.

Always examine the patient for signs of concomitant pulmonary embolism; particularly aim to identify more subtle signs that may be easily missed (e.g., sinus tachycardia and tachypnoea).[26][27] See our topic Pulmonary embolism.

Assess the clinical probability of DVT using the Wells score (unless the patient is pregnant - see Suspected DVT in pregnancy below).[12][26][27] [ Modified Wells score for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) Opens in new window ]

There are several risk assessment models available to assess the clinical probability of DVT; however, the Wells score provides a reproducible method to determine the clinical probability of DVT and is the most widely accepted and validated pretest probability tool used in diagnostic algorithms for DVT.[26][85][86]

The two-level Wells score categorises patients as ‘DVT likely’ (Wells score ≥2) or ‘DVT unlikely’ (Wells score <2).[12][26][27]

A three-level iteration of the Wells score (where patients are categorised into low, moderate, or high clinical likelihood of DVT) is available but the two-level score is generally preferred in practice.[26][27]

Practical tip

The Wells score may underestimate the probability of DVT in certain patient groups, such as patients who misuse intravenous drugs.[87] In practice, categorise patients who inject drugs into a femoral vein as ‘DVT likely’.

Wells score elements | Score |

|---|---|

Active cancer (any treatment within past 6 months) | 1 |

Calf swelling where affected calf circumference measures >3 cm more than the other calf (measured 10 cm below tibial tuberosity) | 1 |

Prominent superficial veins (non-varicose) | 1 |

Pitting oedema (confined to symptomatic leg) | 1 |

Swelling of entire leg | 1 |

Localised pain along distribution of deep venous system | 1 |

Paralysis, paresis, or recent cast immobilisation of lower extremities | 1 |

Recent bed rest for >3 days or major surgery requiring regional or general anaesthetic within past 12 weeks | 1 |

Previous history of DVT or pulmonary embolism | 1 |

Alternative diagnosis at least as probable | -2 |

Clinical probability* | |

DVT unlikely | <2 (probability, 15%) |

DVT likely | ≥2 (absolute risk is approximately 40%) |

*Two versions of the risk assessment model have been validated: two categories (DVT unlikely or likely) or three categories (low, intermediate, or high clinical probability. The simplified version (producing two score categories) is presented as it is likely the easiest to use in clinical settings.

Use the Wells score in combination with a diagnostic algorithm - see Diagnostic algorithm above.[12][26][27] The National Health Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) recommends the following:[12]

If the patient is categorised as ‘DVT likely’, organise a venous ultrasound, with the result available within 4 hours.[12][60] Start therapeutic anticoagulation if proximal DVT is confirmed[12]

If the patient is categorised as ‘DVT unlikely', order a D-dimer with the result available within 4 hours.[12]

See Quantitative D-dimer level and Venous ultrasound below for next steps, or if the results of investigations aren’t available within 4 hours.

If a whole-leg ultrasound confirms distal (calf) DVT, check your local protocol for recommendations on whether and how to start anticoagulation; there is debate in the guidelines.

In the UK, common practice is to start anticoagulation unless the patient has a high risk of bleeding or the DVT is not extensive (<5 cm). Seek advice from a haematologist if the patient has a high bleeding risk or the DVT is not extensive. See Confirmed distal (calf) DVT under Management recommendations for more information.

Suitability of D-dimer testing depends on:[12][26][27]

Whether the patient’s Wells score has categorised the patient as ‘DVT likely’ (Wells ≥2) or ‘DVT unlikely’ (Wells <2)

AND

The availability of venous ultrasound.

If the patient is pregnant, do not use D-dimer testing (or the Wells score) to confirm or rule out DVT.[26][27] See Suspected DVT in pregnancy below for more information.

If D-dimer testing is indicated, consider:[12]

Fully quantitative point-of-care D-dimer testing if laboratory facilities are not available (e.g., in a primary care setting)

An age-adjusted D-dimer test threshold if the patient is aged over 50 years.

Practical tip

If D-dimer testing is required, always order this before giving anticoagulation; a false negative D-dimer result can occur if blood is drawn after giving anticoagulation.[26]

DVT likely (Wells ≥2)

Venous ultrasound is the first-line investigation for patients deemed ‘DVT likely’.[12][26][27] See Venous ultrasound below. However, request D-dimer testing if the result of venous ultrasound is:[12]

Negative

OR

Not available within 4 hours. After the D-dimer test, start interim therapeutic anticoagulation, and organise a venous ultrasound with the result available within 24 hours.[12]

DVT unlikely (Wells <2)

Request D-dimer testing for all patients categorised as ‘DVT unlikely’.[12][26][27]

If the D-dimer level has been taken but the result is not available within 4 hours, start interim therapeutic anticoagulation.

If the D-dimer level is elevated, organise:[12]

A venous ultrasound, with the result available within 4 hours

OR

Interim therapeutic anticoagulation, and a venous ultrasound with the result available within 24 hours.

A normal D-dimer level excludes the diagnosis of DVT; consider alternative causes.[12]

Practical tip

Be aware that an elevated D-dimer level is non-specific and is frequently abnormal in patients without DVT who are older, are acutely ill, have underlying hepatic disease, have an infection, or are pregnant.

More info: D-dimer

D-dimer is a breakdown product of cross-linked fibrin; if there is an acute clot, D-dimer level is likely to be elevated. A quantitative or highly sensitive D-dimer test is therefore a useful test to exclude the presence of an acute DVT.

There are many tests available for D-dimer, but the most reliable are highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay tests. Each of the multiple tests that are available on the market has its own normal cut-off value. D-dimer can be reported in different units, so the specific cut-off value for the test being used should be noted.[88]

D-dimer has a high negative predictive value, which can reduce the need for further imaging or immediate anticoagulation with its associated risks. However, D-dimer also has a low positive predictive value, regardless of the patient group.

Venous ultrasonography is the first-line method of imaging.[12][26]

Choose to use venous ultrasound based on whether the patient’s Wells score has categorised them as ‘DVT likely’ or ‘DVT unlikely’, and the result of D-dimer testing (if this is indicated).[12] A positive venous ultrasound confirms the diagnosis of DVT.[12][26][27]

In the UK, different centres may use either proximal or whole-leg venous ultrasound. Check your local protocol to determine the recommended strategy.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends using proximal venous ultrasound only.[12] However, the European Society of Vascular Surgery recommends whole-leg ultrasound if you suspect distal (calf) DVT.[26] Both strategies have advantages and disadvantages.

More info: Ultrasound approaches

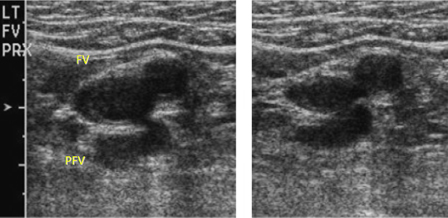

Diagnosis of DVT using B-mode ultrasound is based on the inability to completely collapse the walls of the vein in the transverse plane by pressing down on the vein with a transducer probe (the presence of thrombus prevents compression).

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Short-axis ultrasound view showing the femoral vein (FV) and profunda femoris vein (PFV) adjacent to the femoral artery before compression (left) and compressed (right)From the collection of Jeffrey W. Olin; used with permission [Citation ends].

There are two well-validated approaches to venous ultrasound of the leg: proximal and whole leg.

Proximal-leg ultrasound, recommended by UK-based NICE, assesses only the veins above the calf.[12] Proximal-leg ultrasound is a quick and simple investigation that doesn't require extensive training and therefore is more readily available than whole-leg ultrasound. However, it can miss a DVT that doesn't completely occlude the vein, or is situated in the iliac or calf veins. If the patient is categorised as ‘DVT likely' (Wells ≥2), proximal-leg ultrasound must be repeated after 6 to 8 days if the initial scan is negative, to exclude any undetected calf-vein DVTs that have propagated proximally.[12] Whole-leg ultrasound is recommended by the European Society of Vascular Surgery if you suspect distal (calf) DVT.[26]

Whole-leg ultrasound assesses the veins of both the upper leg and calf. It takes longer to perform, and is technically more demanding, than proximal-leg ultrasound. However, it is possible to reach a diagnostic conclusion in a single session of whole-leg ultrasound. Some UK centres advocate repeating the whole-leg ultrasound if the patient has a negative whole-leg ultrasound, and is categorised as ‘DVT likely’ or has a positive D-dimer. Whole-leg ultrasound can also identify calf-vein DVT. The usefulness of detecting a calf-vein DVT is debated because this might resolve without treatment (therefore its detection can lead to over-diagnosis and potentially over-treatment with anticoagulation, putting the patient at risk of possible bleeding complications).

The subsequent rate of VTE following a negative diagnostic evaluation does not appear to meaningfully differ between whole-leg ultrasound and serial proximal ultrasound.[89]

Colour flow ultrasound is sometimes performed in conjunction with B-mode image ultrasonography.[27]

Findings can include reduced or absent spontaneous flow, lack of respiratory variation, intraluminal echoes, or colour flow patency abnormalities.

A curvilinear probe may be used to attempt to visualise the iliac veins, but this modality does not allow for compression.

The absence of respiratory variations on colour flow ultrasound raises the suspicion of a proximal venous obstruction.

If a whole-leg ultrasound confirms distal (calf) DVT, check your local protocol for recommendations on whether and how to start anticoagulation; there is debate in the guidelines.

In the UK, common practice is to start anticoagulation unless the patient has a high risk of bleeding or the DVT is not extensive (<5 cm). Seek advice from a haematologist if the patient has a high bleeding risk or the DVT is not extensive. See Confirmed distal (calf) DVTunder Management recommendations for more information.

DVT likely (Wells ≥2)

Organise a venous ultrasound, with the result available within 4 hours.[12][60]

If the result of a proximal-leg ultrasound is negative, order D-dimer testing.[12] If the result of D-dimer testing is:[12]

Positive, organise a repeat venous ultrasound 6 to 8 days later but do not start interim therapeutic anticoagulation. If this repeat ultrasound is negative, consider alternative causes[12]

Negative, consider alternative causes.

If the result of a whole-leg ultrasound is negative:

Check your local protocol because recommendations vary

Some UK centres advocate a repeat ultrasound in this scenario

However, the European Society for Vascular Surgery does not recommend a repeat ultrasound, and advises to consider alternative causes.[26]

If the result of the venous ultrasound is not available within 4 hours:[12]

Order a D-dimer test and then offer interim therapeutic anticoagulation

Organise a venous ultrasound with the result available within 24 hours.

DVT unlikely (Wells <2)

If the patient has a positive D-dimer result, organise a venous ultrasound with the result available within 4 hours if possible.[12]

If the result will not be available within 4 hours, start interim therapeutic anticoagulation and organise a venous ultrasound with the result available within 24 hours.[12]

If the result of the venous ultrasound is negative, check your local protocol for advice on next steps because practice varies. NICE in the UK recommends stopping interim anticoagulation (if this has been started) and considering other causes.[12] However, some UK centres may consider repeating the ultrasound (even if whole-leg ultrasound has been used) to identify missed distal (calf) DVT that is extending proximally.

Baseline blood tests

Order the following baseline blood tests before starting anticoagulation:[12][26]

Full blood count

Urea and creatinine

Liver function tests

Clotting screen, which should include prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).

Do not wait for the results of these baseline blood tests before starting anticoagulation.[12] However, ensure you have reviewed (and acted on if necessary) the results within 24 hours of starting anticoagulation.[12]

Further imaging

Consider computed tomography (CT; or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) venography if venous ultrasound is not available or inconclusive.[26][27] Contrast venography (using x-ray) is now rarely used, except when other investigations are inconclusive, or catheter-based treatment is considered.[26]

Note that these recommendations don’t cover pregnant patients - see Suspected DVT in pregnancy below if your patient is pregnant.

Other indications for CT (or MRI) venography include:

Detection of more proximal thrombosis if this is clinically suspected or suggested by flow patterns on Doppler ultrasound[90]

Detection of other medical conditions that may be an alternative cause of the patient’s symptoms and/or increase the risk of DVT, such as extrinsic venous compression syndromes or pelvic malignancies[26][27]

Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism before insertion of filter devices (although this is not required in practice if anticoagulation has been started)[27]

Planned endovascular treatment.[27]

CT may also be more accurate than ultrasound at detecting thrombosis in larger veins of the abdomen and pelvis.[26][90] However, it requires the use of iodine contrast, and involves radiation exposure (a significant concern, particularly in younger patients).[26] MRI has shown similar sensitivity and specificity to venous ultrasound for diagnosis of DVT, but has been evaluated in far fewer studies, using a variety of different techniques.[27]

Consider the diagnosis of DVT in a pregnant patient based on a high index of clinical suspicion, and ensure close follow-up if DVT is confirmed.[26]

Diagnosis of DVT in pregnant patients is particularly challenging. This is due to several factors, including:

An overlap of the symptoms and signs associated with pregnancy and thrombosis

Higher prevalence of iliac vein thrombosis in pregnant patients compared with non-pregnant patients.[91] Iliac vein thrombosis is difficult to detect using venous ultrasound, particularly if proximal (rather than whole-leg) ultrasound is used

A physiological rise in D-dimer level with each trimester. This means that D-dimer plays a limited role in diagnosis of DVT in pregnant patients[92]

The Wells score not being validated in pregnant patients.[27] Do not use the Wells score to risk stratify a pregnant patient with suspected DVT. The LEFt (symptoms in the left leg [L]; calf circumference difference of cm or over [E for oedema]; presentation in the first trimester [Ft]) score is an alternative to Wells if there is low pre-test probability (based on clinical findings) of suspected DVT.[26][27] However, the LEFt score is not widely used in UK practice; always check your local protocols and seek advice from a senior colleague if you are unsure of the best approach for your patient.

Start interim therapeutic anticoagulation (unless contraindicated, and after taking baseline blood tests) if DVT is suspected while waiting for results from investigations.[26][27]

Use venous ultrasound as the initial investigation of choice.[26][27]

Repeat the venous ultrasound if you have high clinical suspicion of DVT but the initial venous ultrasound is negative, particularly if you suspect iliac vein thrombosis.[26][27]

Additional imaging (such as magnetic resonance imaging venography, or conventional contrast venography using x-ray) may be considered in some cases by a specialist, but these techniques may be associated with risks to the foetus.[26][27]

Before starting interim therapeutic anticoagulation for suspected DVT, order baseline blood tests including full blood count, renal and hepatic function, prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).[12][26]

However, do not wait for the results of these before starting anticoagulation.[12]

Review the results (and act on these if necessary) within 24 hours of starting anticoagulation.[12]

Practical tip

If D-dimer testing is required, always order this before giving anticoagulation; a false negative D-dimer result can occur if blood is drawn after the patient has started an anticoagulant.[26]

If possible, choose an interim anticoagulant that can be continued if DVT is confirmed.[12] See Management recommendations for more information about anticoagulation.

Start interim therapeutic anticoagulation (as long as there are no contraindications) if:[12]

The patient is categorised as ‘DVT likely’ (Wells score ≥2) and the result of venous ultrasound is not available within 4 hours

The patient is categorised as ‘DVT unlikely’ (Wells score <2) and:

The D-dimer level has been taken but the result is not available within 4 hours

OR

The D-dimer result is positive, and a venous ultrasound has been arranged with the result available within 24 hours

You suspect DVT clinically in a pregnant patient.[27] Do not wait for the results of imaging.[27]

Stop interim therapeutic anticoagulation if venous ultrasound is negative.[12]

An unprovoked DVT is a DVT in a patient who had no pre-existing, major, transient provoking risk factor in the prior 3 months.[12]

Major provoking risk factors include: major surgery; trauma; significant immobility (bedbound, unable to walk unaided, or likely to spend a substantial proportion of the day in bed or in a chair); pregnancy or puerperium; use of oral contraceptive/hormone replacement therapy).

An unprovoked DVT may be suggestive of an underlying condition so further investigations are sometimes warranted.

Undiagnosed cancer

In any patient diagnosed with unprovoked DVT who is not known to have cancer:[12]

Review medical history

Review baseline blood tests including full blood count, renal and hepatic function, prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT)

Offer a physical examination.[26]

Do not offer further investigations for cancer for patients with an unprovoked DVT unless they have relevant clinical symptoms or signs.[12] Occult cancer is present in approximately 3% to 5% of patients with an unprovoked DVT.[93]

These recommendations are from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK. However, note that the European Society for Vascular Surgery recommends clinical examination and sex-specific cancer screening (but without routine extensive screening for cancer) if the patient has an unprovoked DVT.[26]

Evidence: Cancer screening

The evidence supporting screening for undiagnosed cancer after unprovoked venous thromboembolism is inconclusive.

A screening strategy that was proposed in the SOMIT trial included pelvic and abdominal computed tomography combined with mammography and sputum cytology. This was recommended as the most effective and least harmful approach for patients.

However, no 5-year survival benefit was found when this approach was compared with basic clinical evaluation.[94][95]

Thrombophilia testing

Consider testing for hereditary thrombophilia in patients who don't have an identifiable risk factor and have a first-degree relative who has had a venous thromboembolism, if it is planned to stop anticoagulation.[12][26]

Do not routinely offer thrombophilia testing to first-degree relatives of people with a history of DVT and thrombophilia.[12]

Consider testing for antiphospholipid antibodies in patients who have had an unprovoked DVT if it is planned to stop anticoagulation treatment.[12][26] In practice, this is usually only done if the patient is under 50 years of age.

Practical tip

Be aware that tests for hereditary thrombophilia and antiphospholipid antibodies can be affected by anticoagulation; specialist advice may be needed.[12]

More info: Thrombophilia

Thrombophilia commonly refers to five hereditary conditions (factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene 20210A, deficiencies in antithrombin, protein C deficiency, and protein S deficiency) and antiphospholipid syndrome (an acquired condition). However, many gene variants and acquired conditions modify thrombosis risk.[96] Antiphospholipid antibodies may predict a higher risk of future thrombosis following an initial venous thromboembolism event, and may impact selection of anticoagulant therapy.[40]

If the patient has a confirmed DVT, do not routinely investigate for pulmonary embolism (PE) unless the patient has relevant symptoms or signs.[26]

If the patient has a confirmed proximal DVT, signs or symptoms of PE, and is haemodynamically stable, further investigation for PE is not needed because the patient will require anticoagulation regardless of whether they have PE.[27]

If the patient is haemodynamically unstable with signs of right ventricular dysfunction but PE is unable to be confirmed, diagnosis of a proximal DVT justifies thrombolysis.[27]

See our topic Pulmonary embolism for detailed information regarding diagnosis and management.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer