Recommendations

Urgent

Make a working clinical diagnosis of STEMI and start treatment if the patient has signs and symptoms of myocardial ischaemia plus persistent/increasing ST elevation in two or more contiguous leads on the ECG.[2]

Do not wait for cardiac troponin levels to confirm a STEMI.

Give all patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome a single loading dose of aspirin as soon as possible, unless they have aspirin hypersensitivity. [75]

Check your local protocol or discuss the patient with a senior colleague if they have hypersensitivity to aspirin.

Perform all of the following in tandem as soon as a clinical diagnosis of STEMI has been made.[2][71][75]

Immediately assess the patient’s eligibility for coronary reperfusion therapy (irrespective of age, ethnicity, sex, or level of consciousness).[75]

For most patients the best option will be primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); fibrinolysis is reserved for those without access to timely primary PCI.[2][75]

Gain intravenous access and start continuous haemodynamic monitoring and pulse oximetry.[2]

Avoid placing a cannula that obstructs access to the right radial artery (the commonest entry site for primary PCI).

Give pain relief: an intravenous opioid (e.g., morphine, diamorphine) is recommended plus a concomitant intravenous anti-emetic to prevent vomiting.[82]

Give oxygen therapy only if oxygen saturation is <90%.[2]

Give dual antiplatelet therapy by adding a P2Y12 inhibitor to aspirin.[75]

If the patient is having primary PCI, use prasugrel if they are not already taking an oral anticoagulant, or clopidogrel if they are already taking oral anticoagulation.[75]

Consider an intravenous nitrate (e.g., glyceryl trinitrate, isosorbide dinitrate) if the patient has:[2][82]

Persistent chest pain despite administration of sublingual (or buccal) glyceryl trinitrate

Sustained hypertension

Clinical and/or radiographic evidence of congestive heart failure.

Do not give an intravenous nitrate if there is:

Hypotension secondary to any one of: right ventricular infarction (usually complicating an inferior or extensive anterior STEMI); severe aortic stenosis or left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; pre-existing cardiomyopathy

Persistent hypotension secondary to another cause

Use of a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (e.g., avanafil, sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenafil) for erectile dysfunction within the last 48 hours.

Seek immediate specialist input from the interventional cardiology team.[2]

If you are managing the patient at a non-PCI capable hospital, contact the interventional cardiology team at your designated PCI-capable hospital to discuss immediate transfer.

Do not give anticoagulant therapy if the patient is likely to be eligible for primary PCI.[2][71]

Anticoagulation will be started by the interventional cardiology team in the catheterisation laboratory.

If the patient is having fibrinolysis, start anticoagulation at the same time.[2][71][75] Select enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin (unless streptokinase is used for thrombolysis, in which case choose fondaparinux).[146]

Continue anticoagulation until revascularisation (if fibrinolysis is followed by PCI) or for the duration of hospital stay up to a maximum of 8 days.[2][71]

The optimal time delay between successful fibrinolysis and PCI has not been clearly defined; however, a time window for PCI of 2-24 hours after successful fibrinolysis is recommended.

In a patient who has had a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest:[2][147][148][149][150][151]

Primary PCI is the treatment of choice if there is ST-segment elevation on the post-ROSC ECG or life-threatening arrhythmia

If there is no ST-segment elevation on the post-ROSC ECG then:

Exclude non-coronary causes of cardiac arrest

Perform urgent echocardiography

Strongly consider a referral to cardiology for urgent angiography if there is a high index of suspicion of ongoing myocardial ischaemia despite no ST-segment elevation

When deciding whether to take a survivor of cardiac arrest (with or without ST-segment elevation) to the catheterisation laboratory for urgent angiography ± PCI:[2]

Consider each case on its individual merits and seek senior advice

Take account of factors associated with the cardiac arrest that will influence the chance of a good neurological outcome.

If a patient with STEMI has cardiogenic shock, seek urgent senior support – coronary angiography ± PCI is indicated.[2][75]

Key Recommendations

If there is a high clinical suspicion of STEMI or a clinical diagnosis of STEMI has been made, seek immediate specialist input from cardiology.

The established cornerstone of STEMI management is a combined strategy of:[2][75]

Coronary reperfusion therapy – primary PCI or fibrinolysis plus

Antithrombotic therapy – with dual antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation.

Choice of coronary reperfusion therapy

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Selection of the most appropriate reperfusion strategy. PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary interventionCreated by the BMJ Knowledge Centre [Citation ends].

For most patients with STEMI, primary PCI is the preferred reperfusion strategy provided it can be delivered within 120 minutes of the time when fibrinolysis could have been given.[75][81]

Multiple trials have shown it has better outcomes (in terms of reduced mortality, reinfarction, or stroke) and less intracranial bleeding than fibrinolysis if administered in a timely manner by an experienced team.

Select primary PCI as the preferred reperfusion strategy in patients with acute STEMI, if both the following apply:[75][81]

Symptom onset <12 hours ago AND

PCI can be delivered as soon as possible and at the latest within 120 minutes of the time when fibrinolysis could have been given.

Give fibrinolysis (unless contraindicated) if there is a lack of access to timely primary PCI.[2][75] Give anticoagulation at the same time as giving fibrinolysis. Give dual antiplatelet therapy immediately afterwards.[75]

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends a fibrin-specific drug such as alteplase or tenecteplase. It also recommends streptokinase (a non-fibrin-specific drug) as an option in some patients. Check local protocols for advice on choice of fibrinolytic drug.[152]

Fibrinolysis can be administered as part of the pre-hospital management of STEMI, in which case an intravenous bolus dose of tenecteplase (or reteplase if available) is preferred as the other drugs are administered by intravenous infusion.[2][152]

If your patient is not at a PCI-capable hospital, transfer them to one immediately after fibrinolysis has been given.

Assess the success of fibrinolysis with an ECG after 60-90 minutes.[75]

If primary PCI cannot be delivered within 120 minutes of STEMI diagnosis, seek a specialist cardiology opinion to support your choice of reperfusion strategy.[2][71][153]

The clinical efficacy of thrombolysis diminishes as the time from symptom onset increases.[72][154]

Therefore, the later the patient presents, the more consideration should be given to transferring for primary PCI instead, even if the delay is likely to exceed 120 minutes.[2][74]

If your patient experiences spontaneous resolution of ST-segment elevation and complete symptom relief after taking glyceryl trinitrate:[2]

Refer to cardiology

Aim for early inpatient coronary angiography within 24 hours.

Seek immediate specialist advice from cardiology for any patient with a working diagnosis of STEMI who presents >12 hours after symptom onset.

Coronary angiography ± primary PCI is recommended if there is:[2][75]

Evidence of continuing myocardial ischaemia

Haemodynamic instability or cardiogenic shock

Life-threatening arrhythmias.

A routine primary PCI strategy should be considered in STEMI patients presenting late (12-48 hours) after symptom onset (class IIa).[2]

If your patient has ongoing ischaemic symptoms suggestive of MI BUT no ST-segment elevation on the ECG, primary PCI should be considered if one or more of the following is present:[2]

Cardiogenic shock or haemodynamic instability

Acute heart failure presumed secondary to ongoing myocardial ischaemia

Recurrent or refractory chest pain despite medical treatment

Life-threatening arrhythmia

Signs and symptoms suggestive of mechanical complications of acute MI

Recurrent dynamic ST-segment or T-wave changes, especially intermittent ST-segment elevation.

Time targets for the management of STEMI

The benefits of reperfusion in reducing mortality and improving myocardial salvage decline rapidly with time.[2][75]

It is, therefore, vital to take every step possible to ensure the chosen reperfusion strategy (primary PCI or fibrinolysis) is delivered as quickly as possible.

The 2023 European Society of Cardiology acute coronary syndrome guideline sets widely accepted maximum time-to-treatment targets as follows.[2]

Interval | Target |

|---|---|

First medical contact to ECG and STEMI diagnosis | <10 minutes |

STEMI diagnosis to primary PCI | <120 minutes If this time target cannot be met, consider fibrinolysis |

STEMI diagnosis to primary PCI if the patient’s first medical contact is at a hospital | <60 minutes if the patient presents to or is in a PCI-capable hospital <90 minutes if the patient presents to or is in a non-PCI-capable hospital and needs transferring |

STEMI diagnosis to administration of a bolus/infusion of a fibrinolytic drug (if primary PCI cannot be accessed within 120 minutes) | <10 minutes |

Start of fibrinolysis to ECG assessment of its success or failure | 60-90 minutes |

If fibrinolysis is successful, time interval from starting fibrinolysis to early coronary angiography | 2-24 hours |

Long-term management of STEMI

Long-term management should include aspirin (plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for up to 12 months as part of dual antiplatelet therapy), an ACE inhibitor, a beta-blocker, and a statin, as well as cardiac rehabilitation and modification of risk factors for cardiovascular disease.[63][75][155]

The established cornerstone of STEMI management is a combined strategy of:[2][75]

Coronary reperfusion therapy – either primary percutaneous coronary intervention or fibrinolysis

AND

Antithrombotic therapy – with dual antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation.

The aim is to restore myocardial blood flow as quickly as possible and within guideline-mandated target times to:[2][71][73][74]

Achieve pain relief

Limit myocardial damage/necrosis

Reduce subsequent myocardial remodelling, which can have an adverse effect on predominantly left ventricular and overall function

Minimise morbidity and mortality by preventing or limiting the effect of both electrical and mechanical complications of acute MI.

Give all patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome a single loading dose of aspirin as soon as possible, unless they have aspirin hypersensitivity.[2][75]

Aspirin can be given orally (or via nasogastric tube if oral ingestion is not possible). An intravenous loading dose is used in some countries; however, this formulation is not available in the UK.

Check your local protocol or discuss the patient with a senior colleague if they have hypersensitivity to aspirin.

After the loading dose, continue with a lower maintenance dose of aspirin as part of ongoing dual antiplatelet therapy unless contraindicated.

Start treatment for STEMI immediately after making a clinical diagnosis – do not wait for cardiac troponin levels to confirm it.[2]

Make a clinical working diagnosis of STEMI based on a combination of:

Signs and symptoms of myocardial ischaemia, plus

Persistent or increasing ST elevation on the ECG.

Perform all of the following in tandem as soon as a clinical diagnosis of STEMI has been made.[2][71][75]

Immediately assess the patient’s eligibility for coronary reperfusion therapy.[2][75]

If eligible, take steps to ensure coronary reperfusion therapy is delivered as quickly as possible – see Choice of coronary reperfusion therapy below.

Do not allow the patient’s age, ethnicity, or sex to influence your assessment of their suitability for reperfusion therapy.[75] Evidence suggests that women tend to receive reperfusion therapy less frequently and/or in a more delayed fashion than men, and are less likely to receive cardiac rehabilitations and secondary prevention medications.[2]

Gain intravenous access and start continuous haemodynamic monitoring and pulse oximetry.[2]

Practical tip

When placing an intravenous cannula, avoid placing it in the right hand or right wrist area as the right radial artery is the usual route used to perform primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Titrated intravenous opioids (e.g., morphine, diamorphine) are the most commonly used option. Give an intravenous anti-emetic concomitantly to prevent vomiting.

Pain relief is important not just for the comfort of the patient but also because it may reduce myocardial and microvascular damage due to reduction of heart rate, cardiac workload, and oxygen consumption.[2]

Consider an intravenous nitrate (e.g., glyceryl trinitrate, isosorbide dinitrate).[2]

Routine use of an intravenous nitrate in STEMI is not recommended as there is no evidence to support its benefits. However, an intravenous nitrate may be useful in patients who have:[2]

Sustained hypertension

Clinical and/or radiographic evidence of congestive heart failure

Titrate the rate of infusion according to the patient’s blood pressure and wider clinical response

Persistent chest pain (residual angina) despite administration of sublingual (or buccal) glyceryl trinitrate (which the patient may have received before arriving at hospital).

Do not give an intravenous nitrate when there is hypotension or right ventricular infarction.

Give oxygen therapy only if saturations are <90% on pulse oximetry.[2]

Evidence: Oxygen therapy in patients with acute MI

There is no evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to support the routine use of inhaled oxygen in people with acute MI without hypoxia, but guidelines vary on their specific recommendations.

There are different recommendations in guidelines on the thresholds for starting oxygen therapy. Guidelines also vary on recommended upper limits for oxygen saturation once oxygen has been started.

The 2023 European Society of Cardiology guideline on the management of acute coronary syndromes recommends that routine oxygen is not given if the arterial oxygen saturation is ≥90%.[2] The evidence underpinning this recommendation includes the AVOID study, a Cochrane review, and the protocol for the DETO2X-AMI (all discussed below).[156][157][158] This guideline recommends oxygen therapy for hypoxic patients with an oxygen saturation <90% (based on limited evidence).

One 2018 BMJ Rapid Recommendation also recommends that oxygen therapy is not initiated in patients with acute MI if the oxygen saturation is ≥90%.[159] This is based on the findings from a large systematic review and meta-analysis that liberal oxygen therapy was associated with higher mortality than conservative oxygen therapy in adults with acute illness (see below).[160]

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline on chest pain of recent onset, last updated in 2016, recommends that supplemental oxygen is not routinely offered to patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome.[82] It recommends oxygen therapy if the patient has an oxygen saturation <94% and is not at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure, aiming for a saturation of 94% to 98%. For patients with COPD who are at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure, it recommends a target oxygen saturation of 88% to 92%, until blood gas analysis is available.[82]

The 2016 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guideline on acute coronary syndrome does not include a specific recommendation on the use of oxygen but does refer to a 2013 Cochrane review stating that it found no conclusive evidence to support the routine use of inhaled oxygen in patients with acute MI.[161][162]

There is a lack of evidence to support the routine use of oxygen in patients with acute MI when there is no hypoxia, although oxygen therapy has commonly been used as part of the initial management of patients with STEMI.

One 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis including seven randomised trials and a total of 7702 patients with acute MI without hypoxaemia found that routine supplemental oxygen did not reduce:[163]

Mortality

Arrhythmias

Heart failure

Recurrent ischaemic events.

The DETO2X-AMI multicentre RCT (published in 2017) compared supplemental oxygen therapy (6 L/minute) with ambient air in 6629 patients with suspected acute MI and an oxygen saturation level of ≥90% on pulse oximetry and found no significant difference in death from any cause at 1 year (hazard ratio 0.97; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.21; P=0.80).[164]

One 2016 Cochrane review including five RCTs compared oxygen with air in 1173 people within 24 hours of onset of suspected or proven acute MI (STEMI or non-STEMI). It found no difference in mortality, pain, or infarct size and the authors stated that they could not rule out a harmful effect.[158]

One 2015 RCT of 441 patients with proven STEMI (the AVOID study, included in the Cochrane review above) found that patients receiving oxygen (at 8 L/minute) had similar mean peak troponin levels but significantly increased creatine kinase levels compared with those receiving air.[156] Patients randomised to receive air were given oxygen via nasal cannula (4 L/minute) or face mask (8 L/minute) if their oxygen saturation fell below 94%, to maintain a target level of 94%. Infarction size on cardiac magnetic resonance at 6 months was increased in patients with oxygen therapy compared with air.[156]

Regarding the upper limit for target oxygen saturation once oxygen has been started, evidence from a large systematic review and meta-analysis on oxygen use in acutely ill adults not at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure (including those with MI) supports a 96% upper limit for target oxygen saturation.

One large systematic review (published in 2018) of 25 RCTs and over 16,000 patients, including a meta-analysis, found that in adults with acute illness (including MI, but also including sepsis, critical illness, stroke, trauma, cardiac arrest, and emergency surgery), liberal oxygen therapy (broadly equivalent to a target saturation >96%) is associated with higher mortality than conservative oxygen therapy (broadly equivalent to a target saturation ≤96%).[160]

In-hospital mortality was 11 per 1000 higher with liberal oxygen therapy versus conservative oxygen therapy (95% CI 2-22 per 1000 more). Mortality at 30 days was also higher with liberal oxygen (RR 1.14; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.29). Studies that were limited to people with chronic respiratory illness or psychiatric illness, on extracorporeal life support, receiving hyperbaric oxygen therapy, or having elective surgery were all excluded from the review.[160]

A lower target oxygen saturation of 88% to 92% is appropriate if the patient is at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure.[82][165]

Give a P2Y12 inhibitor in addition to aspirin given in the initial phase, as part of dual antiplatelet therapy.

Check your local protocol when deciding which P2Y12 inhibitor to use and the timing of this.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the following:[75]

If the patient is eligible for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), start dual antiplatelet therapy during PCI:

Prasugrel, in combination with aspirin, if the patient is not already taking an oral anticoagulant

For patients aged 75 years and over, the bleeding risk of using prasugrel needs to be weighed up against its effectiveness. If the bleeding risk from prasugrel is a concern in these patients, ticagrelor or clopidogrel may be used as alternatives

Clopidogrel, in combination with aspirin, if the patient is already taking an oral anticoagulant

If the patient is having fibrinolysis, start dual antiplatelet therapy immediately afterwards:

Ticagrelor, in combination with aspirin, unless the patient has a high bleeding risk

Clopidogrel, in combination with aspirin, or aspirin alone, for patients with a high bleeding risk.

Seek immediate specialist input from the interventional cardiology team.[2]

If you are managing the patient within a PCI-capable hospital, this team will be available on site. If not, call the interventional cardiology team at your designated PCI-capable hospital to discuss immediate transfer for coronary reperfusion therapy.[2]

Practical tip

Administration of an intravenous nitrate should not delay transfer to the catheterisation laboratory.

An intravenous nitrate can be given in the catheterisation laboratory by the interventional cardiology team, if needed.

Recanalisation of the occluded infarct artery is the most effective way of relieving refractory chest pain, so the priority is to get the patient to primary PCI as quickly as possible.

For most patients with STEMI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the preferred reperfusion strategy.[2][75][81]

Multiple randomised controlled trials have shown that primary PCI has better outcomes (in terms of reducing mortality, reinfarction, or stroke) and less intracranial bleeding than fibrinolysis provided it can be delivered in a timely manner by an experienced team.[166][167][168][169][170][171]

However, fibrinolysis may be more appropriate when there is a lack of access to timely PCI.[2][75]

The most appropriate coronary reperfusion strategy will depend on:[2][71][74]

Duration of ischaemic symptoms

Persistence or resolution of ST-segment elevation on serial ECGs

Availability of timely access to primary PCI

Whether a patient is first assessed in a PCI-capable or non-PCI-capable hospital

Estimated transfer time from a non-PCI-capable to a PCI-capable hospital

Whether there was a pre-hospital STEMI diagnosis made by trained and fully equipped paramedic team who can administer initial pharmacotherapy

The quality and expertise of the regional network infrastructure in place for STEMI management.

Many patients who present with STEMI are already taking long-term oral anticoagulation for various indications.[2]

This is a relative contraindication for fibrinolysis.

For any such patient, choose a primary PCI strategy for coronary reperfusion therapy, regardless of the anticipated time to access this intervention.

Concurrent anticoagulation and dual antiplatelet therapy is given alongside coronary reperfusion, regardless of whether primary PCI or fibrinolysis is used.

Seek specialist advice if the patient has a separate indication for ongoing oral anticoagulation.

Patients presenting <12 hours from symptom onset

Primary PCI

Select primary PCI as the preferred reperfusion strategy for any patient who had symptom onset <12 hours ago and has:[2][75][166][167][168][169][172]

Ongoing signs and symptoms of myocardial ischaemia, AND

Persistent (or increasing) ST-segment elevation on ECG.

Take steps to ensure that primary PCI will be delivered within 120 minutes of the time when fibrinolysis could have been given.[75][81]

Primary PCI involves immediate transfer to the catheterisation laboratory with the intention of opening the artery with stent placement. Drug-eluting stents are recommended by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines.[2][75] [

]

[

]

[  ]

]

Many hospitals have round-the-clock PCI capability. If yours does not, then arrange immediate transfer to your designated PCI-capable hospital.

If it is not possible to ensure primary PCI within 120 minutes of the time when fibrinolysis could be started, offer fibrinolysis (if not contraindicated) [75]

If your patient has STEMI with cardiogenic shock, seek urgent senior support. Coronary angiography ± primary PCI is indicated.[2][75]

If the patient’s coronary anatomy is unsuitable for PCI, or PCI fails, emergency coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) is recommended.[2]

For more information on supportive management, see Shock.

Practical tip

If your patient experiences a spontaneous resolution of ST-segment elevation, along with complete symptom relief, after taking glyceryl trinitrate, this is suggestive of coronary spasm with or without associated MI.[2]

Refer to cardiology.

Aim for early inpatient coronary angiography (within 24 hours).

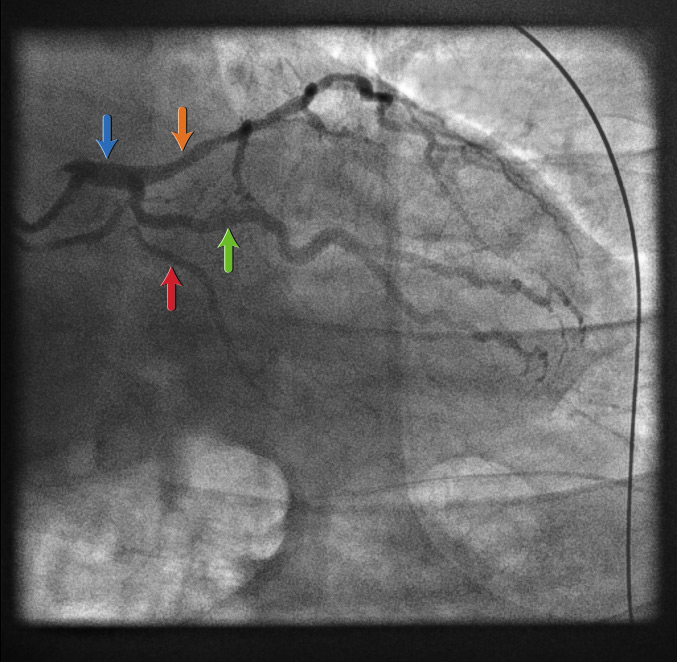

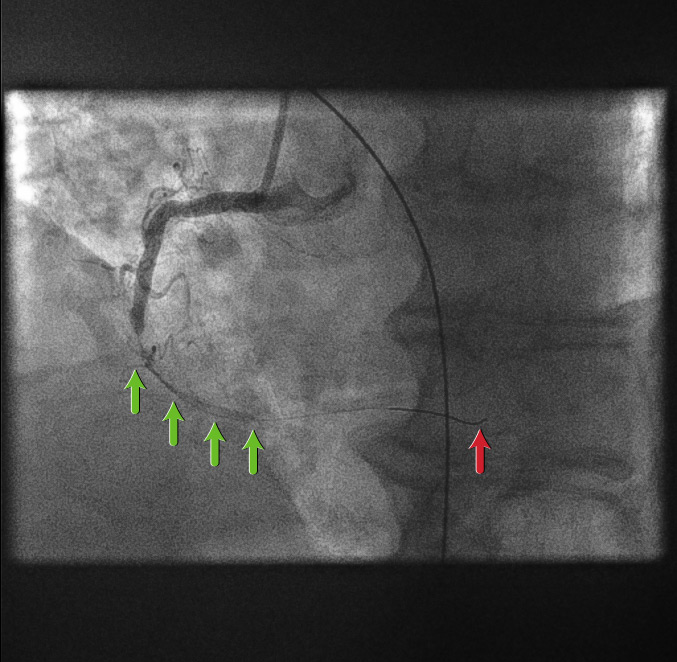

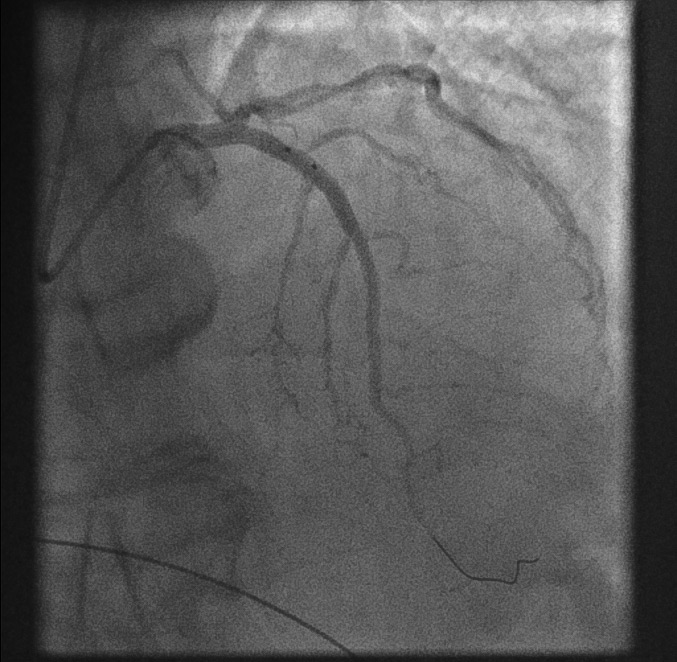

More info: PCI angiograms – inferior STEMI case example

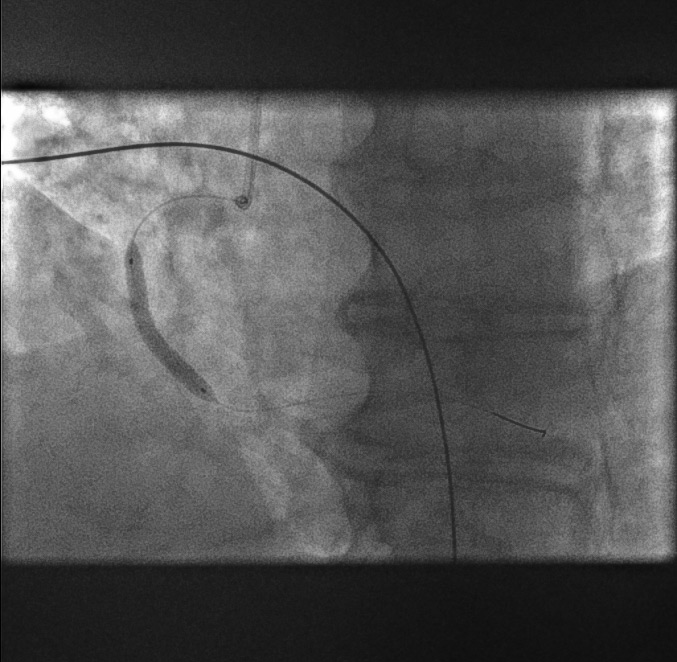

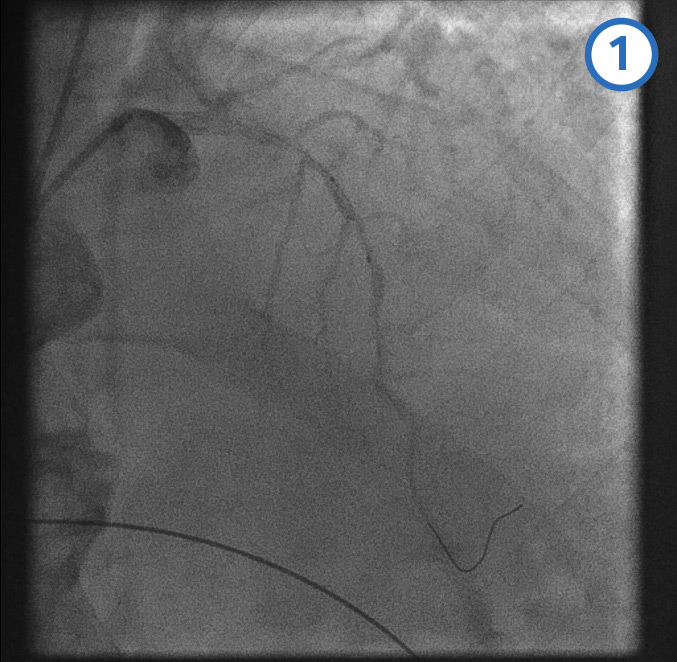

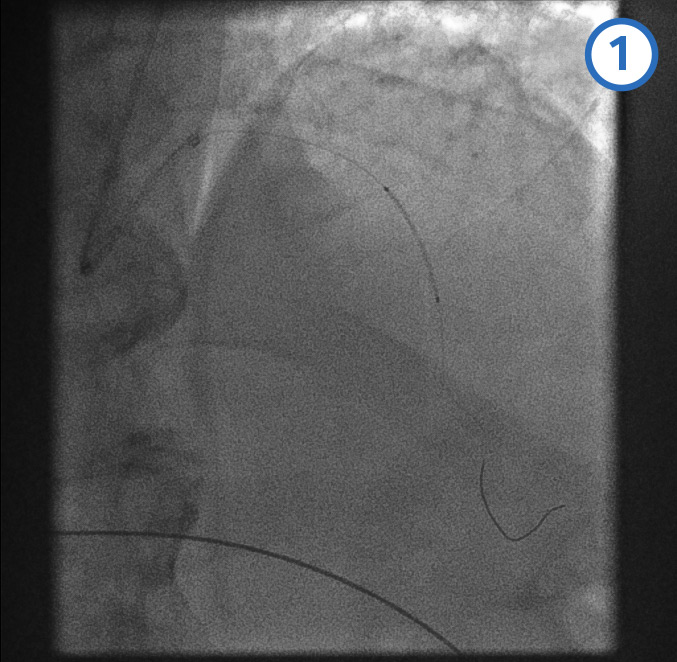

Left main coronary artery: right anterior oblique view[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left main coronary artery: right anterior oblique viewFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

70-year-old man admitted with crushing central chest pain

Inferior ST elevation on ECG

This would suggest a right coronary artery (RCA) occlusion so an angiogram of the left coronary artery system with a diagnostic catheter are taken first

Bear in mind an inferior STEMI can also be associated with a left circumflex (LCx) occlusion

This view allows you to see:

Left main stem (LMS) (blue arrow)

Proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery (orange arrow)

True atrioventricular circumflex (AVCx) (red arrow), which is a small vessel in this case

A large obtuse marginal (OM) branch artery of the LCx

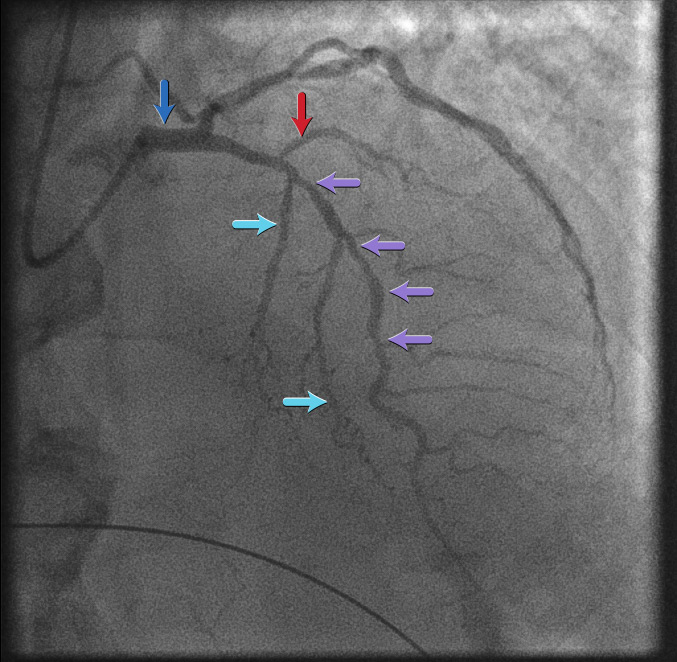

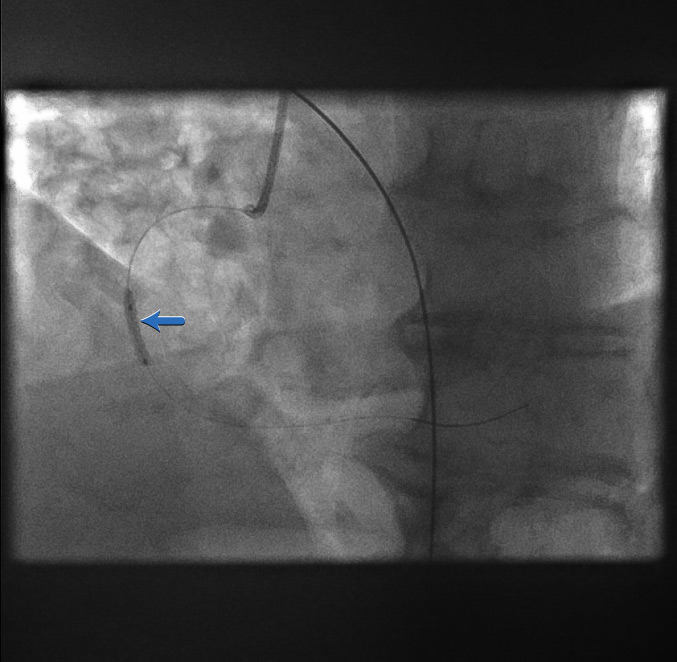

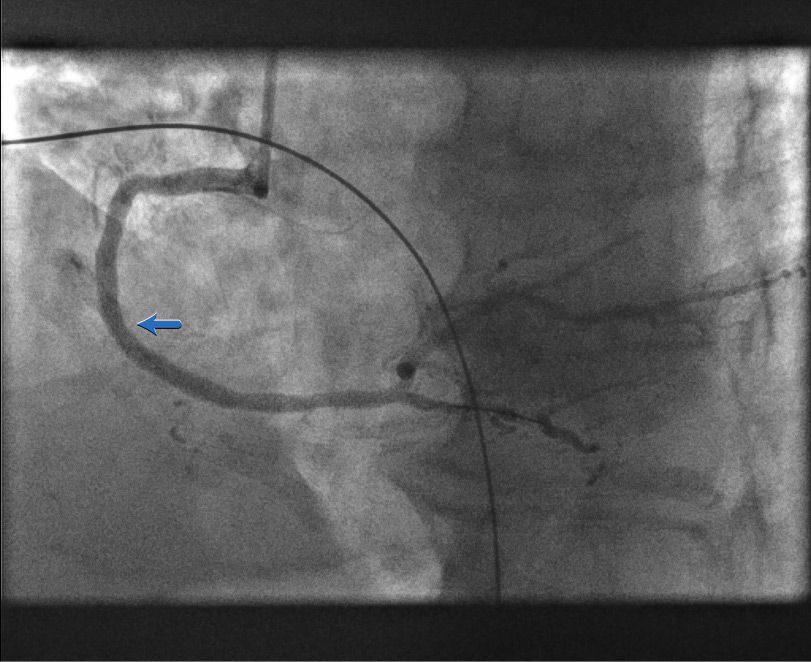

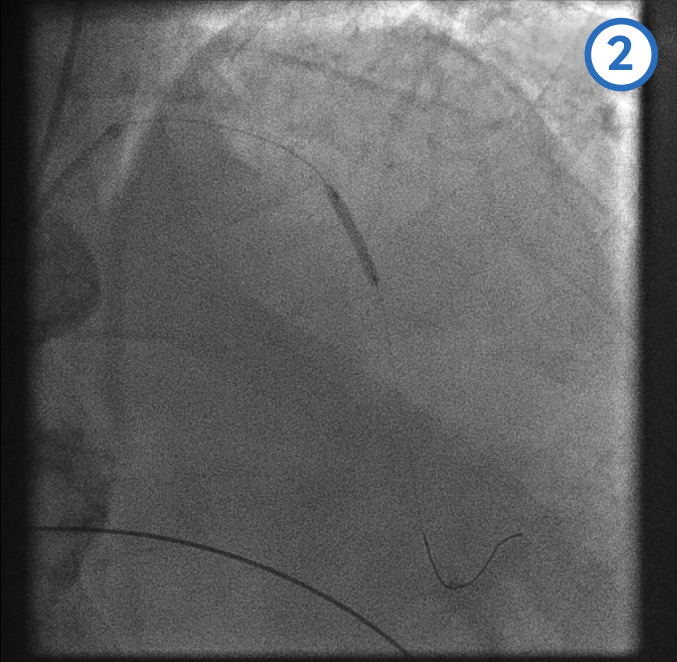

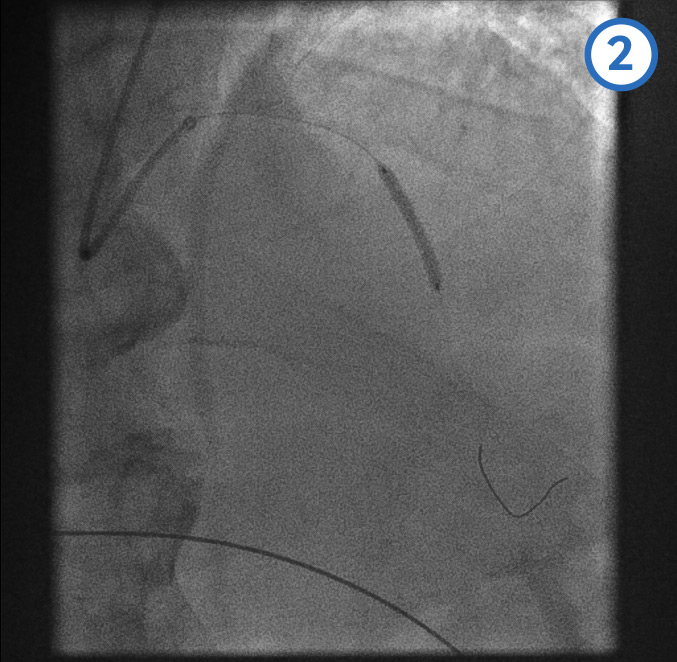

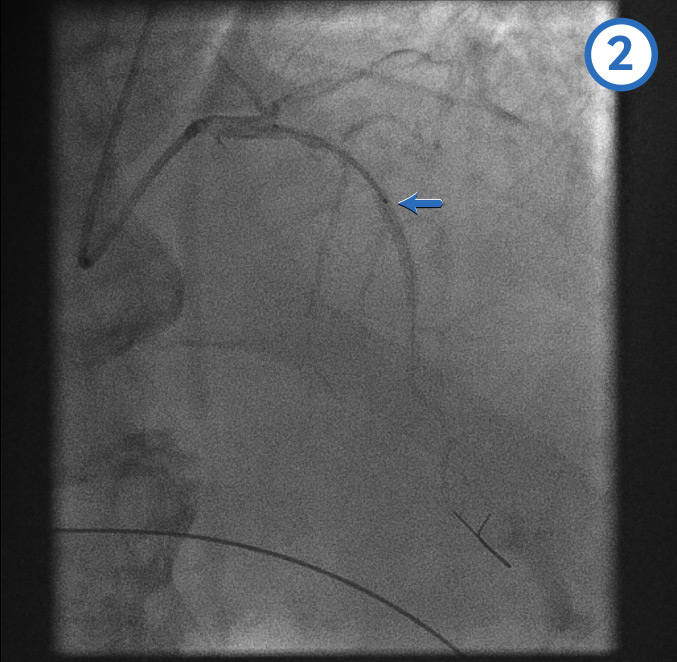

Left main coronary artery: posterior anterior cranial view[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left main coronary artery: posterior anterior cranial viewFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

This view shows the LAD artery

The LAD artery here is diffusely diseased throughout its mid course (purple arrows)

Septal branches of the LAD artery are indicated by the turquoise arrows

The red arrow corresponds to a diagonal branch of the LAD artery

The LMS is shown by the blue arrow

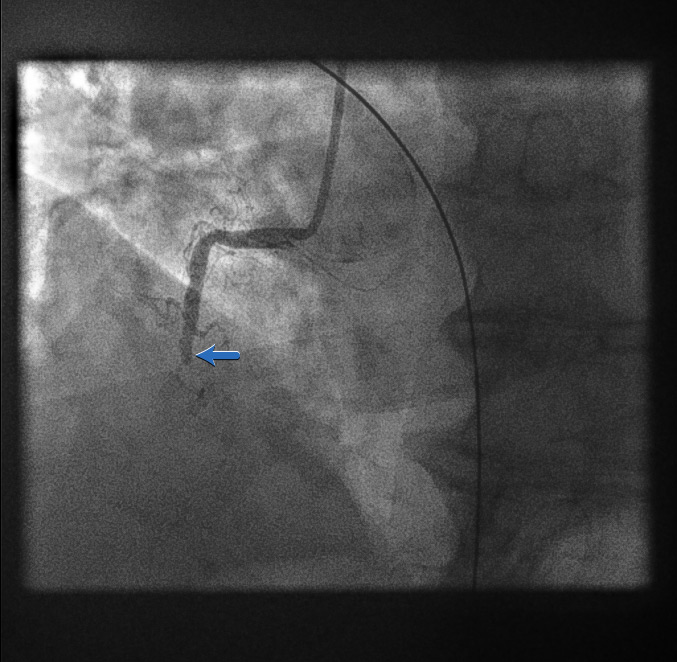

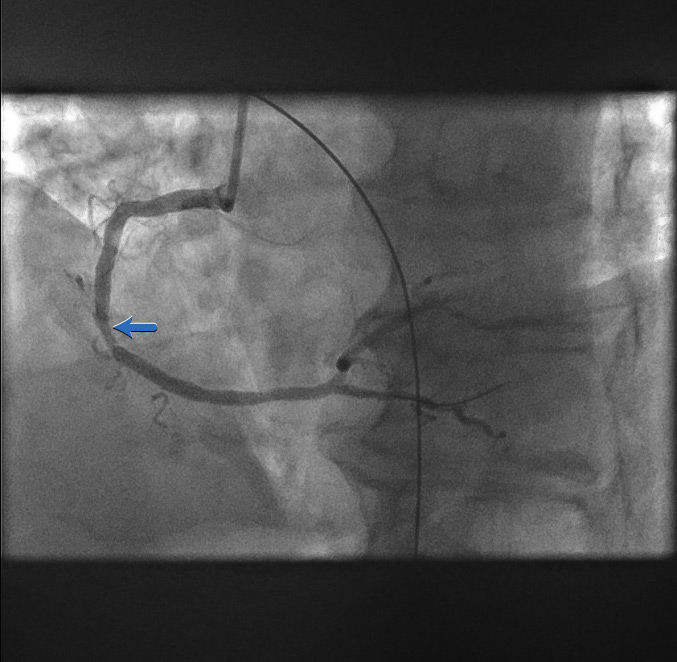

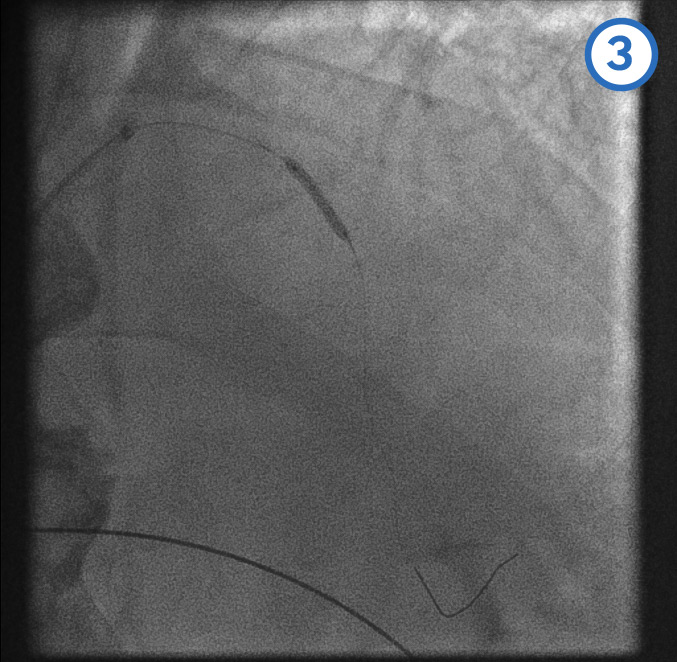

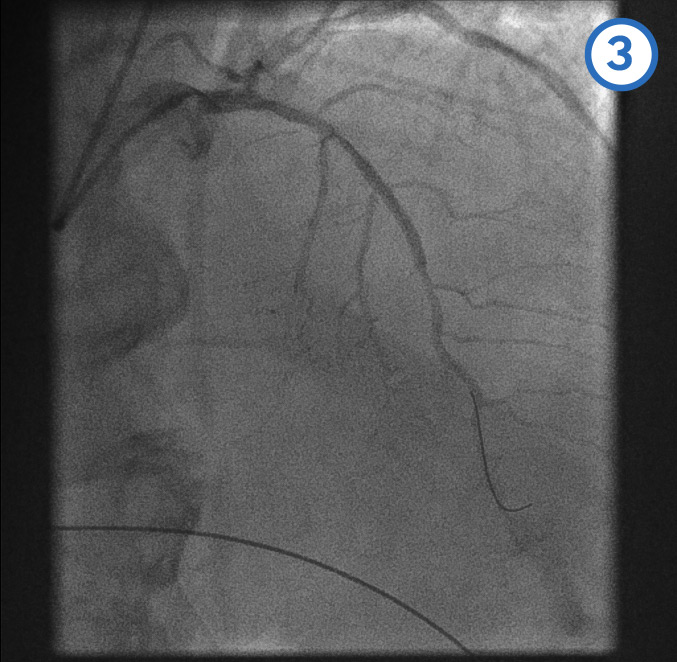

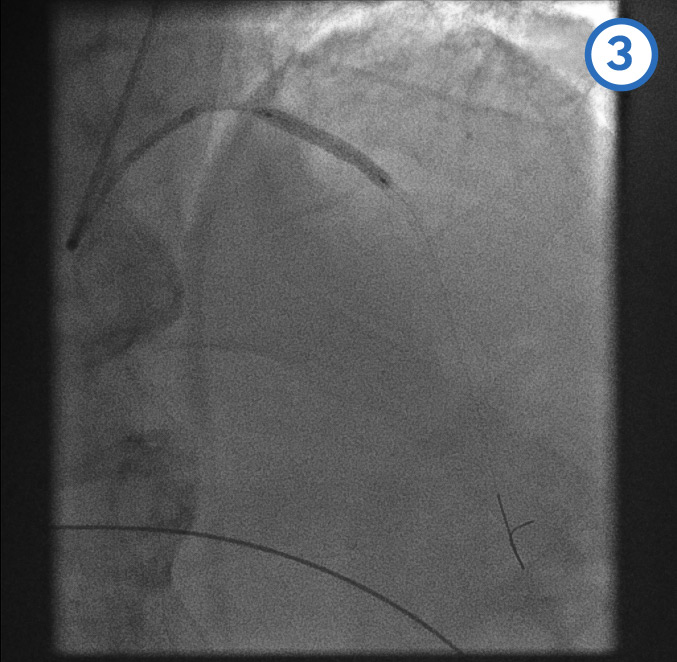

Right coronary artery: left anterior oblique view[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Right coronary artery: left anterior oblique viewFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

As the initial left coronary artery angiogram showed no occlusion, we would typically assume the occlusion is in the RCA

Therefore, a guide catheter (stiffer and larger calibre compared with a diagnostic catheter) would be used to intubate the RCA ostium

Here the initial angiogram confirms an acute total occlusion of the mid RCA (blue arrow)

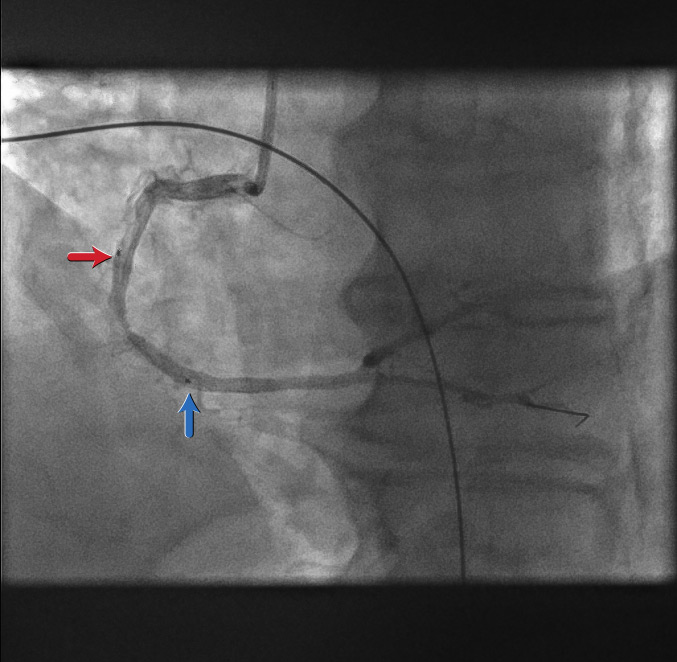

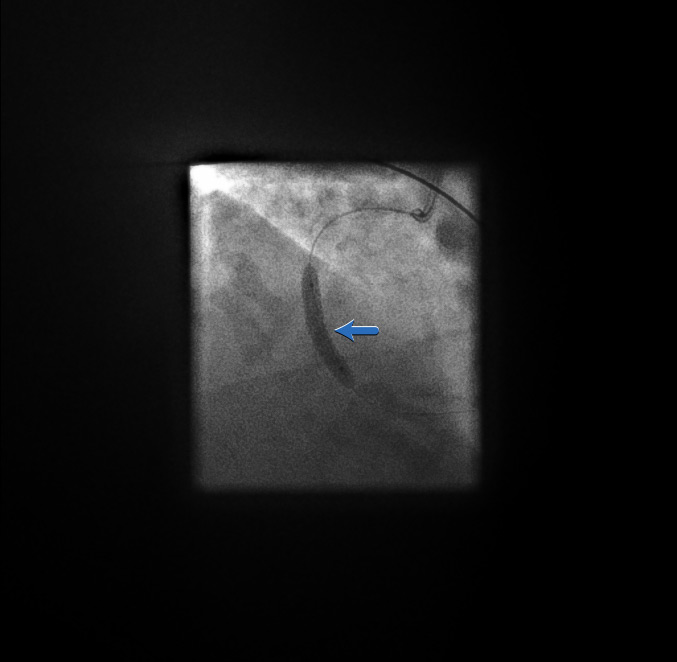

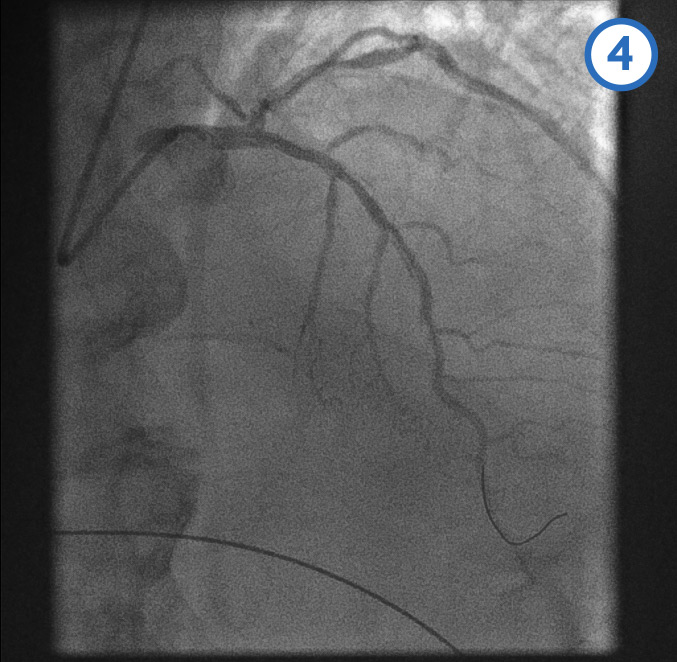

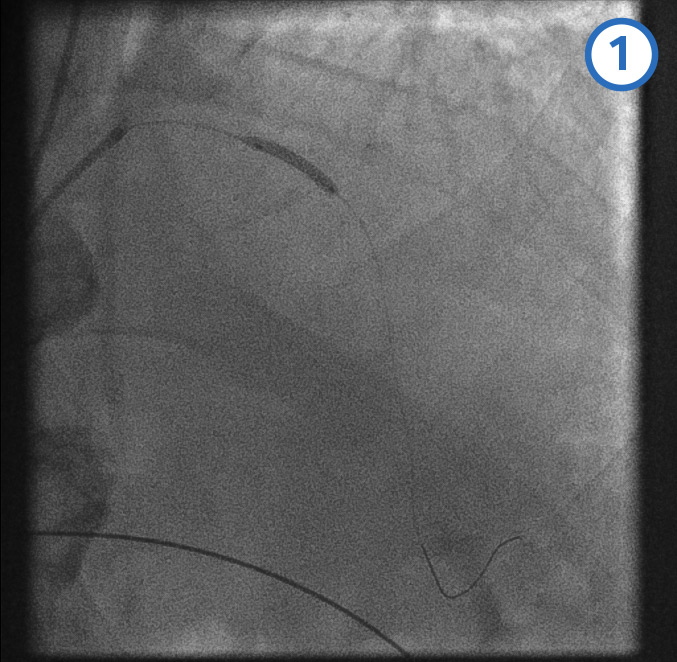

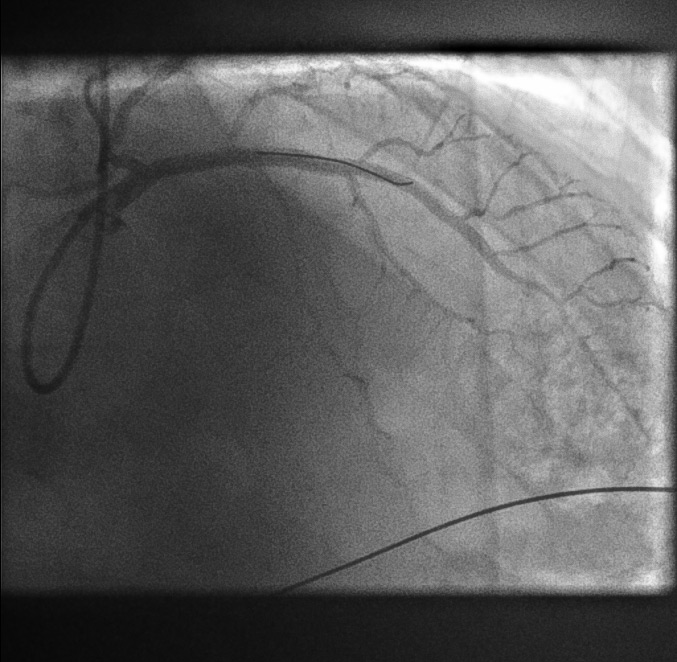

Coronary guidewire deployment[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Coronary guidewire deploymentFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

Before introducing any equipment into a coronary artery, the patient is given a bolus dose of unfractionated heparin anticoagulation, adjusted according to weight

A coronary guidewire is then deployed into the distal RCA (red arrow)

Introduction of the guidewire already starts to restore coronary flow (green arrows)

First balloon dilatation[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: First balloon dilatationFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

A balloon is passed over the coronary guidewire and inflated across the point of the original acute occlusion (blue arrow)

Restoration of coronary flow[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Restoration of coronary flowFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

The first balloon inflation restores flow to the RCA

Now the full outline of the artery can be seen

The area of stenosis and likely atherosclerotic plaque rupture is shown by the blue arrow

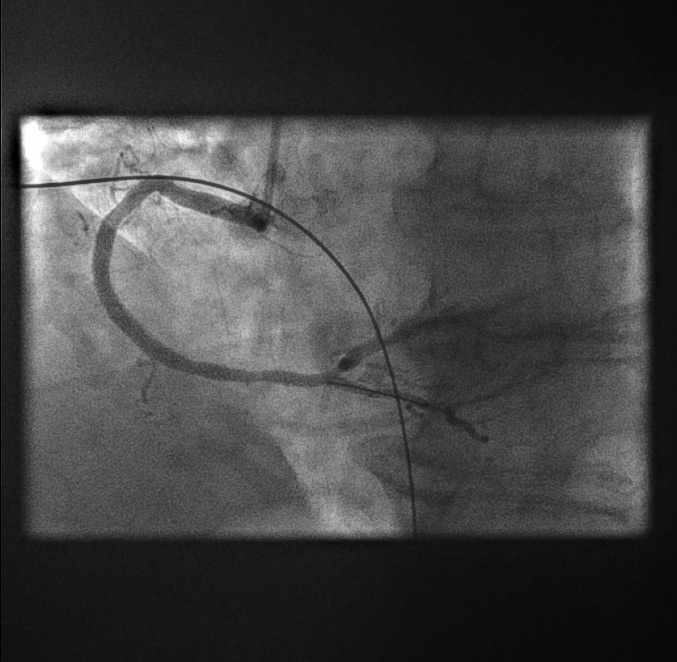

Stent positioning[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Stent positioningFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

The proximal (red arrow) and distal (blue arrow) stent markers are shown here

A decision has been made to stent from what is perceived to be ‘normal’ artery to ‘normal’ artery covering the culprit lesion

Stent deployed[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Stent deployedFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

The stent is sized according to diameter and length in millimetres

Stent deployment transiently re-occludes the vessel, which can cause pain for the patient and haemodynamic changes

After stent deployment[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: After stent deploymentFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

The stent is now expanded within the RCA

There remains an area of underexpanded stent as shown by the blue arrow

Underexpansion can be seen directly using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography (OCT)

Here the underexpansion assumption is based solely on angiographic appearance

Stent post-dilatation[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Stent post-dilatationFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

A post-stent balloon dilatation (blue arrow) is performed to ensure adequate stent expansion

Underexpansion of a stent can lead to acute stent thrombosis

RCA primary angioplasty: final result[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: RCA primary angioplasty: final resultFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

There is an excellent angiographic result

The stent appears fully expanded angiographically with reference to the proximal and distal vessel

Left anterior descending artery pre-dilatation[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left anterior descending artery pre-dilatation image 1From the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left anterior descending artery pre-dilatation image 2From the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left anterior descending artery pre-dilatation image 2From the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left anterior descending artery pre-dilatation image 3From the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left anterior descending artery pre-dilatation image 3From the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left anterior descending artery pre-dilatation image 4From the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left anterior descending artery pre-dilatation image 4From the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

Complete versus infarct-related artery-only (IRA) revascularisation in patients with multi-vessel disease during STEMI remains an area of open debate

The ESC acute coronary syndrome guideline advocates IRA-only revascularisation in patients with cardiogenic shock during the index procedure, with consideration for staged PCI of non-IRA stenoses[2]

For haemodynamically stable patients, the ESC recommends revascularisation of non-IRA lesions either during the index procedure or within 45 days[2]

In this case the decision was made to revascularise the LAD during the index procedure

A coronary guidewire is deployed in the distal LAD (image 1)

The mid (image 2) and proximal (image 3) LAD is then dilated with a balloon

Image 4 shows the LAD after the serial balloon dilatations

Mid-LAD artery stent deployment [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mid-LAD artery stent deployment image 1 - stent positioned in the mid-LAD arteryFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mid-LAD artery stent deployment image 2 - stent balloon inflatedFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mid-LAD artery stent deployment image 2 - stent balloon inflatedFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mid-LAD artery stent deployment image 3 - post mid-LAD stent deployedFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mid-LAD artery stent deployment image 3 - post mid-LAD stent deployedFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

Proximal LAD stent deployment[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proximal LAD stent deployment image 1 - following the mid-LAD stent deployment the proximal vessel is pre-dilatedFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proximal LAD stent deployment image 2 - proximal stent is positioned with the distal marker (blue arrow) overlapping/within the proximal end of the previously deployed mid-LAD stentFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proximal LAD stent deployment image 2 - proximal stent is positioned with the distal marker (blue arrow) overlapping/within the proximal end of the previously deployed mid-LAD stentFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proximal LAD stent deployment image 3 - proximal stent deployedFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proximal LAD stent deployment image 3 - proximal stent deployedFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

Post-dilatation of overlapping stents[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Post-dilatation of overlapping stentsFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

The same balloon of the proximal stent is then used to post-dilate the overlap between the proximal and mid-LAD stents

Final LAD stenting result[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Final LAD stenting result: posterior anterior cranial viewFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Final LAD stenting result: right anterior oblique cranial viewFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Final LAD stenting result: right anterior oblique cranial viewFrom the personal collection of Dr Aung Myat (used with permission) [Citation ends].

Conclusion:

The patient had complete coronary revascularisation with primary angioplasty to the occluded RCA and non-IRA angioplasty to the LAD artery. The patient made an excellent recovery and was discharged home 72 hours after admission.

Fibrinolysis

Give fibrinolysis (unless contraindicated) if primary PCI cannot be delivered within 120 minutes of the time when fibrinolysis could be given.[75][81]

The ESC recommends that fibrinolysis should be given within 10 minutes of making the clinical diagnosis of STEMI.[2]

Check your local protocols for advice on the preferred fibrinolytic drug and how it should be administered. See Choice of fibrinolytic drug below.

Start anticoagulation at the same time as giving fibrinolysis and start dual antiplatelet therapy immediately afterwards.[2][71][75] See Antithrombotic co-therapy given with fibrinolysis below.

If primary PCI cannot be delivered within 120 minutes of STEMI diagnosis, seek a specialist cardiology opinion to support your choice of reperfusion strategy.[2][71][153]

The greatest benefit of fibrinolysis is observed when given <2 hours after symptom onset. Its clinical efficacy diminishes as time from symptom onset increases.[72][154]

Therefore, the later the patient presents, the more consideration should be given to transferring for primary PCI instead – discuss the options with cardiology.[2][74]

If your patient is not already at a PCI-capable hospital, transfer them to one immediately after giving fibrinolysis.[2]

This is so that rescue PCI can be performed if fibrinolysis fails or angiography ± PCI can be arranged if fibrinolysis is effective.

Use an ECG 60-90 minutes after administering fibrinolysis to assess whether it has been successful.[2][75]

If fibrinolysis has failed (<50% ST-segment resolution at 60-90 minutes), offer immediate coronary angiography, with follow-on PCI if indicated. Do not repeat fibrinolytic therapy.[2][75]

If fibrinolysis is successful, consider angiography during the same hospital admission for patients who are clinically stable.[75]

The ESC guidelines recommend arranging angiography ± PCI of the infarct-related artery within 2-24 hours.[2]

Several randomised trials and two meta-analyses have shown that early routine angiography (with PCI if needed) after fibrinolysis reduces the rate of reinfarction and recurrent ischaemia compared with a watchful waiting strategy. The benefits of early routine PCI following fibrinolysis were seen across patient subgroups and without any increased risk of adverse events such as stroke or major bleeding.[173][174][175]

If the patient has recurrent myocardial ischaemia after fibrinolysis, seek immediate specialist advice from cardiology. PCI may be indicated.[75]

The ESC guideline recommends immediate rescue PCI if, at any time following fibrinolysis, the patient develops haemodynamic or electrical instability, worsening ischaemia, or persistent chest pain.[2]

Emergency angiography ± PCI is recommended if, at any time following fibrinolysis, the patient has:

Heart failure or cardiogenic shock[2]

Recurrent ischaemia or evidence of re-occlusion after initially successful fibrinolysis.[2][176][177]

Practical tip

The ESC acute coronary syndrome guideline lists the contraindications to fibrinolytic therapy as follows:[2]

Absolute contraindications

History of intracranial haemorrhage or stroke of unknown origin at any time

Ischaemic stroke in the last 6 months

Central nervous system damage, neoplasm, or arteriovenous malformation

Major trauma/surgery/head injury within the last 1 month

Gastrointestinal bleeding within the last 1 month

Bleeding disorder

Aortic dissection

Non-compressible punctures within the last 24 hours (e.g., liver biopsy, lumbar puncture)

Relative contraindications

Transient ischaemic attack in the last 6 months

Oral anticoagulant therapy

Pregnancy or within 1 week postnatal

Refractory hypertension (systolic BP >180 mmHg and/or diastolic BP >110 mmHg)

Advanced liver disease

Infective endocarditis

Active peptic ulcer

Prolonged or traumatic cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

If primary PCI is not available within 120 minutes but your patient has a contraindication to fibrinolysis:

Seek immediate advice from the interventional cardiology team

For a patient with an absolute contraindication to fibrinolysis, primary PCI will normally be the preferred management strategy despite the delay in accessing it.

Evidence: Role of fibrinolysis in STEMI

Fibrinolytic therapy remains an important evidence-based intervention in settings where primary PCI cannot be offered in a timely manner.

Several landmark studies demonstrated the benefits of fibrinolysis in patients with STEMI (prior to the advent of primary PCI).

The 1988 Second International Study of Infarct Survival (ISIS-2) proved that the benefits of aspirin and fibrinolytics (e.g., streptokinase) were additive and associated with improved 10-year survival following acute MI.[178]

The Fibrinolytic Therapy Trialists’ Collaborative Group (1994) demonstrated highly significant benefits in saving lives and helped to establish the time window when fibrinolytic therapy is most effective.[154]

The study demonstrated highly significant absolute mortality reductions from fibrinolysis of about:

30 per 1000 for those presenting within 0-6 hours of symptom onset

20 per 1000 for those presenting 7-12 hours after symptom onset.

There was a statistically uncertain benefit of about 10 per 1000 for those presenting at 13-18 hours (with more randomised evidence needed in this group to assess reliably the net effects of treatment).

The 1993 GUSTO trial compared different fibrinolysis strategies.[179][180]

It demonstrated a benefit of 14% reduction in mortality (95% CI, 5.9% to 21.3%) for an accelerated tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) versus streptokinase (the standard fibrinolytic treatment at the time). Alteplase (recombinant t-PA) was used in the trial.

The trial randomly assigned 41,021 patients with evolving acute MI to 4 different fibrinolytic strategies. The data for the primary end point of 30-day mortality for each treatment arm was as follows:

Streptokinase plus subcutaneous heparin = 7.2%

Streptokinase plus intravenous heparin = 7.4%

t-PA plus intravenous heparin = 6.3%

Streptokinase plus t-PA plus intravenous heparin = 7.0%.

A significant excess of haemorrhagic strokes was observed for accelerated t-PA (P = 0.03) and for the combination strategy (P <0.001), as compared with streptokinase only.

The 2013 STREAM trial provided further support for fibrinolysis as an appropriate reperfusion strategy for STEMI when primary PCI cannot be delivered in a timely manner – especially if followed by routine early angiography ± PCI (a 'pharmaco-invasive strategy').[171]

The STREAM trial was conducted at a time when primary PCI was established as the standard of care for STEMI.

In the trial, 1892 STEMI patients presenting within 3 hours of symptom onset but unable to have primary PCI within 1 hour were randomly assigned to:

Primary PCI or

Pre-hospital bolus tenecteplase (with a half-dose used in patients ≥75 years) plus clopidogrel plus enoxaparin before transport to a PCI-capable hospital

Patients had emergency angiography if fibrinolysis failed

If fibrinolysis was successful, patients had routine angiography within 6-24 hours after randomisation.

There was no significant difference between the primary PCI and fibrinolysis groups in the primary composite end point of death, shock, congestive heart failure, or reinfarction within 30 days.

More intracranial haemorrhages occurred in the fibrinolysis group.

The ESC guideline recommendation is that fibrinolysis should be given within 10 minutes of STEMI diagnosis.[2]

The extent to which the delay-to-PCI time diminishes the advantages of primary PCI over fibrinolysis has been widely debated, and more research is needed.

It is clear that if delay to treatment is similar, primary PCI is superior to fibrinolysis in reducing mortality, reinfarction, or stroke.[2]

However, fibrinolysis can be administered expeditiously and the longer the delay to primary PCI, the lower the benefits over fibrinolysis. The exact cut-off point at which the delay to access PCI makes fibrinolysis the better reperfusion strategy is based on weak evidence.

Multivariate meta-analyses provide further evidence to support a pharmaco-invasive strategy, suggesting it is safer and more effective than facilitated PCI or fibrinolysis, where primary PCI is not available in a timely fashion.[181]

Patients presenting >12 hours from symptom onset

Seek immediate specialist advice from cardiology to discuss management options for any STEMI patient who presents >12 hours after symptom onset.

Coronary angiography ± primary PCI is recommended if there is:

If your patient has ongoing ischaemic symptoms suggestive of MI but no ongoing ST-segment elevation on the ECG, primary PCI should be considered if one or more of the following is present:[2]

Cardiogenic shock or haemodynamic instability

Acute heart failure presumed secondary to ongoing myocardial ischaemia

Recurrent or refractory chest pain despite medical treatment

Cardiac arrest or life-threatening arrhythmia

Signs and symptoms suggestive of mechanical complications of acute MI

Recurrent dynamic ST-segment or T-wave changes, especially intermittent ST-segment elevation.

Discuss urgently with cardiology any patient who presents >12 hours after symptom onset but has no ongoing symptoms.[2][182]

Routine primary PCI strategy should still be considered in patients presenting between 12 and 48 hours after symptom onset. However, if the time since symptom onset is >48 hours and the patient is now asymptomatic, routine PCI of an occluded infarct-related artery is not recommended.[2]

Fibrinolysis is not indicated.

Survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

Primary PCI is the treatment of choice for any patient in whom a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is achieved after cardiac arrest and who has:[2][147][148][149][150][151]

ST-segment elevation on their post-ROSC ECG.

In a patient who has been resuscitated from cardiac arrest but has no ST-segment elevation on their post-ROSC ECG:[2]

Exclude non-coronary causes of cardiac arrest:

Non-cardiogenic shock

Respiratory failure

Cerebrovascular event

Pulmonary embolism

Intoxication/poisoning

Perform urgent echocardiography[2]

Assess left and right ventricular function

Identify other mechanical complications of acute MI

Consider referral to cardiology for urgent angiography if there is a high index of suspicion of ongoing myocardial ischaemia despite no ST-segment elevation, for example:

Chest pain prior to cardiac arrest

Presence of cardiac risk factors

Established coronary artery disease or previous myocardial infarction

Ambiguous or abnormal post-ROSC ECG.

To make a decision on whether to take a survivor of cardiac arrest (with or without ST-segment elevation) to the catheterisation laboratory for urgent angiography ± PCI:[2]

Consider each case on its individual merits and seek senior advice

Take account of factors associated with a greater chance of a good neurological outcome, including:[183]

A witnessed cardiac arrest

Immediate bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation and/or early arrival of emergency medical services (<10 minutes)

An initial shockable rhythm

Sustained ROSC achieved within 20 minutes.

The European Society of Cardiology recommends that, in general, patients with ROSC and persistent ST-segment elevation should undergo angiography ± PCI. Although there is a lack of dedicated trials, registry reports suggest good outcomes for PCI in these patients, particularly for those who are non-comatose at initial assessment.

See Cardiac arrest.

The benefits of reperfusion in reducing mortality and improving myocardial salvage decline rapidly with time.[2][75]

It is, therefore, vital to take every step possible to ensure the chosen reperfusion strategy (primary percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] or fibrinolysis) is delivered as quickly as possible.

The 2023 European Society of Cardiology acute coronary syndrome guideline sets widely accepted maximum time-to-treatment targets as follows:[2]

Interval | Target |

|---|---|

First medical contact to ECG and STEMI diagnosis | <10 minutes |

STEMI diagnosis to primary PCI | <120 minutes If this time target cannot be met, consider fibrinolysis |

STEMI diagnosis to primary PCI if the patient’s first medical contact is at a hospital | <60 minutes if the patient presents to or is in a PCI-capable hospital <90 minutes if the patient presents to or is in a non-PCI-capable hospital and needs transferring |

STEMI diagnosis to administration of a bolus/infusion of a fibrinolytic drug (if primary PCI cannot be accessed within 120 minutes) | <10 minutes |

Start of fibrinolysis to ECG assessment of its success or failure | 60-90 minutes |

If fibrinolysis is successful, time interval from starting fibrinolysis to early coronary angiography | 2-24 hours |

Choice of antiplatelet therapy for patients undergoing primary PCI

Give any patient who will undergo primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) dual antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor plus aspirin.[75]

After the initial aspirin loading dose, reduce the aspirin to a lower daily maintenance dose.

Check your local protocol when deciding which P2Y12 inhibitor to use, the timing of this, and the recommended initial loading and ongoing daily doses.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the following:[75]

Prasugrel, in combination with aspirin, if the patient is not already taking an oral anticoagulant

For patients aged 75 years and over, the bleeding risk of using prasugrel needs to be weighed up against its effectiveness. If the bleeding risk from prasugrel is a concern in these patients, ticagrelor or clopidogrel may be used as alternatives

Clopidogrel, in combination with aspirin, if the patient is taking an oral anticoagulant.

The European Society of Cardiology guideline recommends prasugrel or ticagrelor (in combination with aspirin) for patients undergoing primary PCI. Prasugrel should be considered in preference to ticagrelor, but clopidogrel is only indicated when neither of these drugs is available or they are contraindicated.[2]

Cangrelor is a reversible intravenous P2Y12 inhibitor that can be considered if the patient is unable to ingest an oral drug.[2] NICE has yet to make any recommendation on the use of cangrelor.

Always follow your local protocol for P2Y12 inhibitor selection and timing.

Practical tip

Do not use ticagrelor in patients who:

Have active bleeding or a history of intracranial haemorrhage.

Prasugrel is:

Contraindicated in patients with active bleeding or a history of previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack

Not generally recommended in patients aged ≥75 years or those with body weight <60 kg[2][75]

Do not give a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor or fibrinolytics prior to primary PCI.[75]

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (e.g., eptifibatide, tirofiban, abciximab) may be used by the interventional cardiology team during the PCI procedure to tackle a high thrombus burden or no-reflow phenomenon. Abciximab is not currently available in the UK, and shortages in other countries have been reported.

Evidence: Choice of P2Y12 inhibitor for patients undergoing PCI

Third-generation P2Y12 inhibitors prasugrel and ticagrelor are preferred to clopidogrel as part of a dual antiplatelet therapy regimen with aspirin for the treatment of STEMI in patients undergoing primary PCI who are not already on oral anticoagulation.

In November 2020 the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) updated its acute coronary syndromes guidance. This included a network meta-analysis of dual antiplatelet therapy that found prasugrel and ticagrelor were more effective than clopidogrel at both 30 days and 1 year. Although there was some uncertainty at 30 days, prasugrel was more effective than ticagrelor at 1 year, especially for reducing all-cause mortality and reinfarction.[75] These results were driven by 3 large trials, as follows.

In the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial, 13,608 acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients awaiting PCI were randomised to loading and maintenance doses of prasugrel versus clopidogrel.

There was a significant reduction in favour of prasugrel in the combined primary end point of cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal MI, or non-fatal stroke (9.9% vs. 12.1%; hazard ratio [HR] 0.81, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.90; P <0.001).[185]

The PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial randomised 18,624 patients admitted to hospital with an ACS (with or without ST-segment elevation) to loading and maintenance doses of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel.

There was a significant reduction in favour of ticagrelor in the 12-month primary efficacy end point of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke (9.8% vs. 11.7%; HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.92; P <0.001).

Of note, the ticagrelor group also had significantly lower all-cause mortality (4.5% vs. 5.9%, P <0.001).[186]

The ISAR-REACT 5 trial, in which 4018 ACS patients awaiting PCI were randomised to ticagrelor versus prasugrel.

There was a significant reduction in favour of prasugrel in the 12-month primary efficacy end point of all-cause mortality, MI, or stroke (9.3% with ticagrelor vs. 6.9% with prasugrel; HR 1.36, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.70; P = 0.006).[187]

The faster onset of action and greater antiplatelet potency of prasugrel and ticagrelor (compared with clopidogrel) means they carry a greater risk of bleeding. Therefore, clopidogrel is preferred in people already taking an oral anticoagulant.

In the TRITON-TIMI trial, the prasugrel group had a higher risk of life-threatening bleeding versus the clopidogrel group (1.4% vs. 0.9%; P = 0.01).[185]

In the PLATO trial, ticagrelor was associated with a higher rate of major bleeding unrelated to coronary artery bypass grafting compared with clopidogrel (4.5% vs. 3.8%).[186]

In the ISAR-REACT 5 trial there was no significant difference in major bleeding between ticagrelor versus prasugrel (HR 1.12, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.51).[187]

The evidence is less certain for people aged 75 years and over and a reduced dose of prasugrel or alternative treatment should be considered on an individual basis.

NICE noted that the TRITON-TIMI trial adverse events, including major bleeding, were more common with prasugrel than with clopidogrel in people aged 75 years and over. Subsequent trials used a reduced dose of prasugrel in this age group and did not find an increased risk of bleeding.

NICE also stated that more research is required comparing the efficacy of prasugrel, ticagrelor, and clopidogrel in people aged 75 years and over.[75]

The European Society of Cardiology guideline recommends prasugrel or ticagrelor (with preference for prasugrel) in combination with aspirin for patients undergoing primary PCI, with clopidogrel only indicated when neither of these drugs is available or they are contraindicated.[2]

Choice of anticoagulant therapy for patients undergoing primary PCI

Anticoagulation is routinely given during primary PCI.

This will be started by the interventional cardiology team in the cardiac catheterisation laboratory.

Therefore, do not start anticoagulation if your patient is likely to be eligible for primary PCI.

Unfractionated heparin is recommended first line for intravenous anticoagulation.[2][75] Alternatives include:

Bivalirudin (a direct thrombin inhibitor) for patients with a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

Enoxaparin.

Fondaparinux is not recommended as an adjunctive anticoagulant during primary PCI.[2]

It was associated with catheter thrombosis at the time of primary PCI in the OASIS-6 trial.[188]

Routine post-procedural anticoagulation is not required after primary PCI unless there is a separate indication for it, for example:[188]

Full-dose anticoagulation:

Atrial fibrillation

Mechanical heart valve

Left ventricular thrombus

Prophylactic-dose anticoagulation:

Patients at high risk of venous thromboembolism.

If the delay to primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) means fibrinolysis is selected as the most appropriate reperfusion strategy, check your local protocols regarding the choice of fibrinolytic drug.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends a fibrin-specific drug such as alteplase or tenecteplase.[152] It also recommends streptokinase (a non-fibrin-specific drug) as an option in some patients.[152]

The European Society of Cardiology guideline recommends the same drugs plus reteplase (no longer available in the UK).[2] According to these guidelines, you should consider a half-dose of tenecteplase if the patient is aged 75 years or older.[2]

When choosing a fibrinolytic drug take account of:[152]

Balancing the benefit and harm (e.g., stroke risk) of each drug for the individual patient

The importance of avoiding giving streptokinase to a patient who has received it in the past (patients treated with streptokinase may develop antibodies that neutralise the drug if repeat treatment is given)

Your local hospital protocol for reducing delays in the administration of thrombolysis.

To shorten the time to treatment, fibrinolysis can be administered as part of the pre-hospital management of STEMI.[2][152]

This may be part of the emergency care treatment pathway where geographical considerations mean the anticipated time to primary PCI will be >120 minutes.

In such cases, a bolus dose of tenecteplase ( or reteplase if available) is preferred for the sake of practicality as the other fibrinolytic drug options are administered by intravenous infusion.

Transfer to a PCI-capable hospital is indicated in all patients immediately after administration of fibrinolysis.

Antithrombotic co-therapy with fibrinolysis consists of a combination of:

Dual antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor, in addition to aspirin given in the initial phase

Parenteral anticoagulation.

Give any patient having fibrinolysis anticoagulation at the same time as giving fibrinolysis and start dual antiplatelet therapy immediately afterwards (see below). [75]

The choice of parenteral anticoagulation can be:[2]

Enoxaparin – an intravenous bolus dose initially, followed by subcutaneous dosing in patients <75 years of age (patients ≥75 years of age are given subcutaneous dosing only). The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guideline recommends this as the first-choice anticoagulant for patients undergoing fibrinolysis[2][189][190][191]

Unfractionated heparin – a weight-adjusted intravenous bolus followed by an intravenous infusion, recommended by ESC when enoxaparin is not available

Fondaparinux (only if streptokinase is used for fibrinolysis) – an intravenous dose initially, followed by the first subcutaneous dose given 24 hours later.[192]

Ensure anticoagulation co-therapy for any patient undergoing fibrinolysis continues:[2][71]

Up to the point of coronary revascularisation with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI; if performed), or

For the duration of the hospital stay to a maximum of 8 days in total if revascularisation is not performed.[2]

If a pharmaco-invasive strategy is adopted (fibrinolysis followed by angiography ± PCI), then one regimen that is supported by robust data is composed of:[2][171][176][193][194]

Fibrinolysis with intravenous tenecteplase, plus

Oral aspirin and clopidogrel, plus

Intravenous enoxaparin at the time of fibrinolysis, plus

Subcutaneous enoxaparin until the time of revascularisation by PCI.

Give the patient dual antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor plus aspirin immediately after giving fibrinolysis.[75]

After the initial aspirin loading dose, reduce the aspirin to a lower daily maintenance dose.

Check your local protocol when deciding which P2Y12 inhibitor to use, the timing of this, and the recommended initial loading and ongoing daily doses.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends the following:[75]

Ticagrelor, in combination with aspirin, unless the patient has a high bleeding risk

Clopidogrel, in combination with aspirin, or aspirin alone for patients with a high bleeding risk.

The ESC guideline recommends clopidogrel (in combination with aspirin) as the preferred agent.[2]

Evidence: Choice of P2Y12 inhibitor for patients not undergoing PCI

Ticagrelor, a third-generation P2Y12 inhibitor, is preferred to clopidogrel as part of a dual antiplatelet therapy regimen with aspirin for the treatment of STEMI in patients who are not undergoing PCI.

In November 2020 the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) updated its acute coronary syndromes guidance. This included a network meta-analysis of dual antiplatelet therapy.[75]

As prasugrel is only licensed for patients undergoing primary PCI the guideline committee considered the evidence for ticagrelor versus clopidogrel for patients not undergoing PCI.

Most of the evidence was from patients with unstable angina or non-STEMI, as the majority of people with STEMI are managed with PCI; however, this mostly indirect population was felt to be appropriate due to similarities in the basic pathophysiology and the consistent benefits of ticagrelor over clopidogrel in all patients not undergoing PCI.

Ticagrelor reduced reinfarction at 30 days and 1 year. There was some uncertainty around mortality at 30 days but ticagrelor reduced all-cause and cardiac mortality at 1 year.

Ticagrelor also reduced the need for revascularisation at 30 days and 1 year, and stent thrombosis events at 1 year.

Overall, the evidence did not show a clinically important harm with ticagrelor over clopidogrel in terms of bleeding (major or minor) at 30 days or 1 year.

There was a possible increased risk of stroke with ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel, but the absolute difference in number of events was small and the confidence intervals were wide.

Breathing adverse events (e.g., shortness of breath) were more common with ticagrelor at 30 days and 1 year. However, the guideline committee considered these to be mostly reversible.

NICE reported a cost-effectiveness analysis study that showed in medically managed people ticagrelor was cost-effective compared with clopidogrel.

The faster onset of action and greater antiplatelet potency of ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel means it may carry a greater risk of bleeding.

In the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial, ticagrelor was associated with a higher rate of major bleeding unrelated to coronary artery bypass grafting compared with clopidogrel (4.5% vs. 3.8%).[186]

The NICE guideline committee noted that most other studies excluded older people or other groups of people at higher risk of bleeding, and was concerned about the trade off between benefit and harm in these subgroups.

Therefore, the committee agreed that clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin alone may be more appropriate for people with a higher risk of bleeding.[75]

Offer conservative medical management to any patient who is ineligible for any reperfusion therapy.[75]

Ensure the patient still receives dual antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation, and all appropriate secondary prevention therapies.[2][75]

Check your local protocol when deciding which P2Y12 inhibitor to use and the timing of this.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends the following options for dual antiplatelet therapy in patients who are not treated with percutaneous coronary intervention:[75]

Ticagrelor, in combination with aspirin, unless the patient has a high bleeding risk

Clopidogrel, in combination with aspirin, or aspirin alone for patients with a high bleeding risk.

Arrange echocardiography assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction for all STEMI patients.[75]

Ensure all patients are given the following (while taking into account any contraindications).

Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor (unless the patient has a separate indication for anticoagulation - seek specialist advice).[75] Continue the P2Y12 inhibitor used in the acute phase for up to 12 months (unless contraindicated).[75] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK recommends:[75]

For patients who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI):

Prasugrel in those not taking an oral anticoagulant. However, follow your local protocol. Consider ticagrelor or clopidogrel in patients aged 75 years or older if the bleeding risk from prasugrel is a concern.

Clopidogrel in those taking an oral anticoagulant.

For patients who had fibrinolysis:

Ticagrelor unless the patient has a high bleeding risk

Clopidogrel or aspirin alone if the patient has a high bleeding risk.

The European Society of Cardiology recommends 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy as the default strategy, although alternate regimes can be considered in certain circumstances depending on bleeding and ischaemic risks:[2][195]

Single antiplatelet therapy (preferably with a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor, e.g., ticagrelor) for patients who are event-free after 3-6 months of dual antiplatelet therapy, and who are not at high ischaemic risk[196][197][198][199][200][201]

Aspirin or P2Y12 receptor inhibitor monotherapy after 1 month of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with high bleeding risk.[202]

De-escalation of antiplatelet therapy in the first 30 days is not recommended. However, beyond 30 days after an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), de-escalation of P2Y12 receptor inhibitor therapy may be considered as an alternative strategy in those at high bleeding risk.[2] Theoretically, by identifying patients who are unlikely to have a response to clopidogrel by genetic/platelet function testing, there is potential for personalised antiplatelet therapy.[203] However, it is unclear whether de-escalation guided by platelet function testing or genetic testing improves clinical management and outcomes, and such a strategy based on platelet function testing or genetic testing should be prospectively tested in patients who may benefit from de-escalating antithrombotic therapy.[2]

Continue aspirin indefinitely unless the patient has hypersensitivity.

Practical tip

Evidence on the selection and duration of antiplatelet therapy following coronary revascularisation is evolving rapidly, with studies showing potential benefits from different strategies.[204][205]

In the UK, you should check the patient’s clinical report for an individualised plan written by the interventional cardiology team. This should specify what antiplatelet therapy is advised for long-term management, based on current evidence, individual patient factors, and the specific interventions undertaken for each patient.

More info: Antiplatelet therapy for patients with a separate indication for anticoagulation

Seek specialist advice when deciding the duration and type (dual or single) of antiplatelet therapy in the 12 months after STEMI for patients with a separate indication for anticoagulation (e.g., in patients with ongoing atrial fibrillation).

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK recommends taking account of all of the following when deciding about the duration and type (dual or single) of antiplatelet therapy in patients with a separate indication for anticoagulation:[75]

Bleeding risk

Thromboembolic risk

Cardiovascular risk

Patient's wishes.

Be aware that long-term continuation of aspirin, clopidogrel, and oral anticoagulation (triple therapy) significantly increases bleeding risk.

For patients already on anticoagulation who had PCI:[75]

Continue anticoagulation and clopidogrel for up to 12 months

If the patient is taking a direct oral anticoagulant, adjust the dose according to bleeding risk, thromboembolic risk, and cardiovascular risk.

For patients with a new indication for anticoagulation who had PCI:[75]

Offer clopidogrel (to replace prasugrel or ticagrelor) for up to 12 months and an oral anticoagulant licensed for the indication, which best matches the patient's bleeding risk, thromboembolic risk, cardiovascular risk, and wishes.

For patients already on anticoagulation, or those with a new indication, who did not have PCI:[75]

Continue anticoagulation and, unless there is a high risk of bleeding, consider continuing aspirin (or clopidogrel for patients with contraindication for aspirin) for up to 12 months.

Do not routinely offer prasugrel or ticagrelor in combination with anticoagulation in patients with a separate indication for anticoagulation.[75]

An ACE inhibitor

Start this as soon as the patient is haemodynamically stable and continue it indefinitely. Complete upwards dose titration within 4-6 weeks of hospital discharge.[75]

Offer an angiotensin-II receptor antagonist as an alternative if the patient is intolerant to an ACE inhibitor.[75]

Measure renal function, serum electrolytes, and blood pressure before starting an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin-II receptor antagonist.[75] In practice, if the patient has abnormal renal function or blood pressure, start with a low dose and titrate this carefully with close monitoring.

A beta-blocker

Start this as soon as the patient is haemodynamically stable.[75]

Continue the beta-blocker for at least 12 months if the patient does not have reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).[75][206]

Continue the beta-blocker indefinitely if the patient has reduced LVEF.[75]

Evidence shows that a beta-blocker may reduce the short-term risk of a reinfarction and the long-term risk of all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction.[155][207][206][208]

High-intensity statin therapy.[45][63][75]

Non-adherence to statin therapy and failure to achieve lipid targets is associated with an increased cardiovascular mortality following acute MI.[209] Patients should be counselled on the importance of medication adherence.

Target low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol is <1.4 mmol/L (<55 mg/dL) and a ≥50% LDL-cholesterol reduction from baseline. If these targets are not achieved on maximal statin therapy, add ezetimibe.[2][63]

A proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor monoclonal antibody (e.g., evolocumab, alirocumab) may be added to statin and ezetimibe therapy if LDL-cholesterol targets are not achieved despite maximal statin and ezetimibe therapy.[2][63][210][211][212] Treatment can be started during ACS admission or at outpatient follow-up 4-6 weeks later.

Give an aldosterone antagonist (e.g., eplerenone, spironolactone) to any patient with signs or symptoms of heart failure and reduced LVEF.[75]

Start this within 3-14 days of a STEMI and preferably after starting an ACE inhibitor.[75]

Give a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor (e.g., dapagliflozin, empagliflozin) to patients with heart failure when they are clinically stable, regardless of their LVEF.[213][214][215]

Calcium-channel blockers and potassium-channel activators

Do not routinely give calcium-channel blockers.[75]

Consider a non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker, such as verapamil, in a patient without pulmonary congestion or reduced LVEF who has a contraindication to beta-blockers (or when these need to be discontinued).[75]

Do not offer nicorandil (a potassium-channel activator).

Offer cardiac rehabilitation to all patients. This should include an exercise component, health education, stress management, and psychological and social support.

[  ]

Advise all patients on lifestyle changes such as:[2][75]

]

Advise all patients on lifestyle changes such as:[2][75]

Changes to diet

Reduction of alcohol consumption

Smoking cessation

Weight management

Physical exercise

Reduced sedentary time.

Patients without any pre-existing risk factors for cardiovascular disease are at increased risk of early mortality; even patients who are deemed low risk require prompt initiation of evidence-based pharmacotherapy post ACS.[216]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer