Recommendations

Urgent

Record and interpret a resting 12-lead ECG within 10 minutes of the point of first medical contact in any patient with suspected unstable angina (and other acute coronary syndromes [ACSs]).[1]

Discuss the patient immediately with the cardiology team and involve senior support if the ECG shows evidence of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) to activate your local STEMI protocol.[71] See ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

In practice, a diagnosis of unstable angina should be made by a cardiologist.

An initial working diagnosis of non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome is based on the presence of symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischaemia (e.g., acute chest pain) and ECG findings (no evidence of STEMI).[1]

A diagnosis of unstable angina can usually be made if subsequent dynamic troponin testing shows cardiac troponin remaining below the 99th percentile. Diagnostic imaging including invasive coronary angiography, functional (stress) testing, or coronary computed tomography angiography may be useful for patients in whom cardiac troponin and ECG results remain inconclusive.[1] Transthoracic echocardiography may also be of value in patients where there is diagnostic uncertainty, to identify signs of ongoing ischaemia or prior myocardial infarction and to make a swift assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction.[1]

In clinical practice these diagnostic investigations assist in making the diagnosis of unstable angina; however, they cannot exclude the diagnosis completely, merely render the diagnosis unlikely. This is highly likely in coronary vasospasm or with microvascular disease.

Suspect an acute myocardial infarction if the patient is clinically unstable and get urgent input from a senior colleague or cardiologist to arrange immediate invasive coronary angiography (with the intent to perform revascularisation); this is unlikely to be a feature of unstable angina. See ST-elevation myocardial infarction and Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

This includes any patient with:[71][72]

Ongoing or recurrent pain despite treatment

Haemodynamic instability (low blood pressure or shock) or cardiogenic shock; see Shock

Recurrent dynamic ECG changes

Acute left ventricular failure, presumed secondary to ongoing myocardial ischaemia; see Acute heart failure

A life-threatening arrhythmia (ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation) or cardiac arrest after presentation; see Sustained ventricular tachycardias[1]

Mechanical complications such as new-onset mitral regurgitation.[1]

In the community, refer all patients to hospital as an emergency if you suspect an ACS and they:[73]

Currently have chest pain

Are currently pain-free, but have had chest pain within the last 12 hours and a resting 12-lead ECG is abnormal or unavailable

Have had a recent ACS (confirmed or suspected) and develop further chest pain.

Key Recommendations

Consider ACS in any patient presenting with acute chest pain, which includes other areas (e.g., the arms, back, or jaw; epigastric or abdominal pain), especially if this is associated with nausea and vomiting, marked sweating, and/or breathlessness, or particularly a combination of these.[73]

Recognise that presentations where chest pain is not the predominant feature (chest-pain equivalent symptoms) are more common in older patients, women, and patients with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or dementia.[1] These include epigastric pain, indigestion-like symptoms, isolated dyspnoea, and syncope.[1] Women are also more likely to present with middle/upper back pain.

Take into account the history and character of the chest pain, risk factors for cardiovascular disease (particularly a history of ischaemic heart disease) and any previous treatment, and previous investigations for chest pain to determine whether ACS is likely.[73]

Be aware that physical examination may be normal in patients with unstable angina.[2]

Always order, in addition to a resting 12-lead ECG, the following investigations for all patients:

High-sensitivity troponin (within 60 minutes); use this in conjunction with a diagnostic algorithm to rapidly confirm or rule out a myocardial infarction (a summary of the pathway recommended by the European Society of Cardiology is below)[1][74]

Chest x-ray

Full blood count

Urea, electrolytes, and creatinine

Liver function tests

Blood glucose

C-reactive protein

Lipid profile

Coagulation profile

The European Society of Cardiology recommends that patients are classified into one of three pathways as per the results of their high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) values at 0 hour (time of initial blood test) and 1 hour or 2 hours later.

Rule-out pathway: for very low initial hs-cTn or no increase after 1/2 hours: these patients may be appropriate for early discharge and outpatient management.

Rule-in pathway: for high initial hs-cTN or an increase after 1-2 hours: most of these patients will require hospital admission and invasive coronary angiography.

Observe pathway: if neither of the above criteria is met: check hs-cTN at 3 hours and consider echocardiography.

In practice, patients with a raised hs-cTN presenting in the emergency department are often referred to cardiology before a second troponin test.

Suspect acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in any patient with acute chest pain, which includes pain in other areas (e.g., the arms, back, or jaw), that:[73]

Lasts longer than 15 minutes

Is associated with nausea and vomiting, marked sweating, breathlessness, or particularly a combination of these[1][73]

Is either new in onset or occurs as sudden worsening of known stable angina (i.e., recurrent episodes of chest pain lasting longer than 15 minutes that occur frequently and with little or no exertion, or decreasing efficacy of anti-anginal drugs).

In practice, a diagnosis of unstable angina should be made by a cardiologist.

An initial working diagnosis of non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome is based on:

The presence of symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischaemia (e.g., acute chest pain)

ECG findings (no evidence of ST-elevation myocardial infarction; may be normal or may show ST-segment depression, transient ST-segment elevation, or T-wave inversion).

A diagnosis of unstable angina can usually be confirmed if subsequent dynamic troponin testing shows cardiac troponin remaining below the 99th percentile. Diagnostic imaging including invasive coronary angiography, functional (stress) testing, or coronary computed tomography angiography may be useful for patients in whom cardiac troponin and ECG results remain inconclusive.[1] Transthoracic echocardiography may also be of value in patients where there is diagnostic uncertainty, to identify signs of ongoing ischaemia or prior myocardial infarction and to make a swift assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction.

In clinical practice those diagnostic investigations assist in making the diagnosis of unstable angina; however, they can not exclude the diagnosis completely, merely render the diagnosis unlikely. This is highly likely in coronary vasospasm or with microvascular disease.

Unstable angina is defined as myocardial ischaemia at rest or on minimal exertion in the absence of acute injury/necrosis.[1]

Suspect an acute myocardial infarction if the patient is clinically unstable and get urgent input from a senior colleague or cardiology to arrange immediate invasive coronary angiography (with the intent to perform revascularisation); this is unlikely to be a feature of unstable angina. See ST-elevation myocardial infarction and Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. This includes any patient with:[71][72]

Ongoing or recurrent pain despite treatment

Haemodynamic instability (low blood pressure or shock) or cardiogenic shock; see Shock

Recurrent dynamic ECG changes

Acute left ventricular failure, presumed secondary to ongoing myocardial ischaemia; see Acute heart failure

A life-threatening arrhythmia (ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation) or cardiac arrest after presentation; see Sustained ventricular tachycardias[1]

Mechanical complications such as new-onset mitral regurgitation.[1]

Practical tip

Patients may also describe chest pain as pressure, tightness, heaviness, or a burning sensation.[1]

Be aware of non-characteristic presentations such as epigastric pain, indigestion-like symptoms, isolated dyspnoea, or syncope. These are more common in older patients, women, and patients with diabetes.[1] Women are also more likely to present with middle/upper back pain and other non-characteristic symptoms.

In the community, refer all patients to hospital as an emergency if you suspect an ACS and they:[73]

Currently have chest pain

Are currently pain-free, but have had chest pain within the last 12 hours and a resting 12-lead ECG is abnormal or unavailable

Have had a recent ACS (confirmed or suspected) and develop further chest pain.

Practical tip

The European Society for Cardiology recommends to 'Think A.C.S.' at initial assessment of chest pain:[1]

Abnormalities or evidence of ischaemia on ECG assessment

Clinical context: take a targeted clinical history to assess the clinical context of the presentation

Stability: targeted clinical examination to assess for clinical and haemodynamic stability.

The admitting team can decide whether immediate invasive management is required based on this initial assessment.

Check immediately whether the patient currently has chest pain.[73]

If the patient is currently free from chest pain, ask when their last episode of pain occurred, particularly if they have had pain in the last 12 hours.[73]

Ask when the patient’s last episode of chest pain started because this will determine the timing of high-sensitivity troponin testing.[73]

Consider the following to determine whether the chest pain is likely to be cardiac:[73]

The history and character of the patient’s chest pain.[1][73] Useful points to cover include:

Whether the patient has experienced this type of pain before

The nature, severity, and duration of pain

Any associated symptoms[73]

The presence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease.[73] These include:

Diabetes[2]

Hyperlipidaemia[75]

Hypertension[75]

Metabolic syndrome

Renal impairment[2]

Peripheral arterial disease[2]

A history of ischaemic heart disease and any previous treatment[73]

Obesity

Advanced age

Cocaine use

Physical inactivity

Family history of premature coronary artery disease (<60 years of age)

Previous investigations for chest pain.[73]

Ask the patient about other important points:

Be aware that physical examination is generally normal in patients with unstable angina.[2]

Suspect an acute myocardial infarction if the patient is haemodynamically unstable (low blood pressure or shock), has evidence of left ventricular failure, or has a life-threatening arrhythmia (ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation); these are unlikely to be features of unstable angina.[71][72] See Shock, Acute heart failure, Sustained ventricular tachycardias, ST-elevation myocardial infarction, and Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Assess for any signs of active bleeding.

Practical tip

Always remain vigilant for alternate diagnoses.[77]

Examine for signs of aortic dissection (such as radio-radial delay); this is an important differential to consider. See Aortic dissection.

Fever may be suggestive of endocarditis or pneumonia.

Auscultate the lungs for abnormal lung sounds; this may reveal signs of pneumonia or pneumothorax.

Auscultate the heart for added sounds: a friction rub may suggest pericarditis; other murmurs may reveal signs suggestive of valvular stenosis or regurgitation, or endocarditis.

Immediate (within 10 minutes) in all patients

ECG

Record and interpret a resting 12-lead ECG within 10 minutes of the point of first medical contact.[1]

Discuss the patient immediately with the cardiology team and involve senior support if the ECG shows evidence of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) to activate your local STEMI protocol.[1] See ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Be aware that the ECG may be normal in more than 30% of patients.[1] Furthermore, unstable angina is generally not associated with ECG changes (based on the opinion of our experts).

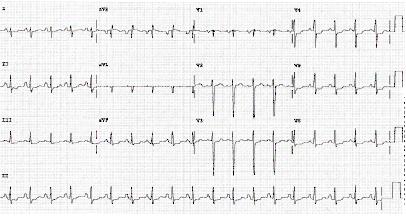

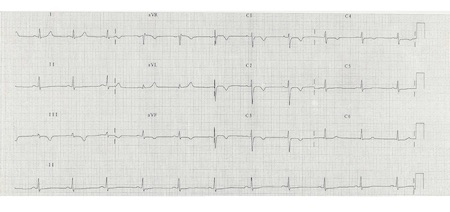

However, abnormal ECG findings that suggest non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (ACS) include:[1]

ST depression; this indicates a worse prognosis

Transient ST elevation

T-wave changes.

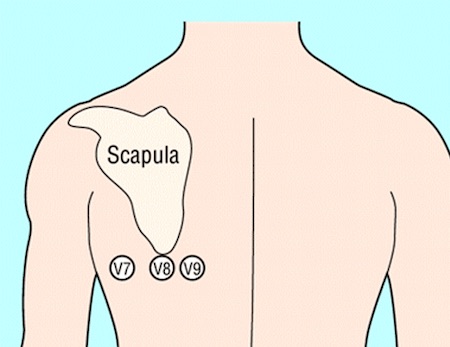

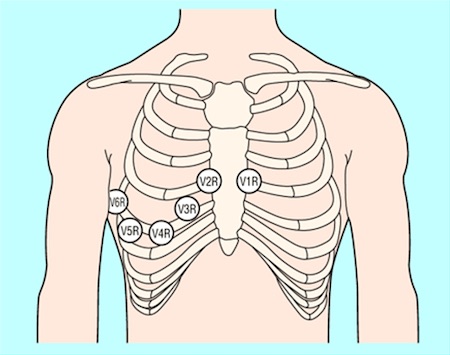

Record additional leads if the standard leads are inconclusive, if total vessel occlusion is suspected, or in cases of suspected inferior STEMI.[1]

Leads V7–V9 may detect left circumflex artery occlusion and leads V3R and V4R may detect right ventricular myocardial infarction.[1]

Order repeated resting ECGs if the patient has recurrent symptoms or you are unsure about the diagnosis.[1]

Always compare the current ECG with previous ECGs wherever possible.[1]

How to record an ECG. Demonstrates placement of chest and limb electrodes.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Position of ECG leads V7-V9Image used with permission from BMJ 2002;324:831 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Position of right precordial ECG leads V3R and V4RImage used with permission from BMJ 2002;324:831 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Position of right precordial ECG leads V3R and V4RImage used with permission from BMJ 2002;324:831 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing inferolateral ST depressionFrom the personal collection of Dr Syed W. Yusuf and Dr Iyad N. Daher, Department of Cardiology, University of Texas, Houston; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing inferolateral ST depressionFrom the personal collection of Dr Syed W. Yusuf and Dr Iyad N. Daher, Department of Cardiology, University of Texas, Houston; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing T wave inversion in leads V1-V4, III and aVF.BMJ Learning/Professor Kevin Tanner; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing T wave inversion in leads V1-V4, III and aVF.BMJ Learning/Professor Kevin Tanner; used with permission [Citation ends].

Acute (within 60 minutes) in all patients

High-sensitivity troponin

Measure high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) immediately after presentation and obtain results within 60 minutes in all patients with suspected ACS to rule out acute myocardial infarction; there will be no dynamic rise above the 99th percentile in patients with unstable angina.[1]

Use a diagnostic algorithm (ideally the 0/1 hour protocol recommended by the European Society of Cardiology, with blood draws at 0 hours and 1 hour) to measure hs-cTn over time in all patients except those who are clinically unstable. Cut-off values for hs-cTn are dependent on the assay used; check your local protocol.[1]

Use the algorithm in the context of other clinical criteria such as a detailed history of the chest pain and any ECG findings.[1]

Some patients may need an additional measurement of troponin at 3 hours (e.g., if the first two hs-cTn measurements of the 0/1 algorithm are inconclusive, and no alternative diagnoses explaining the condition have been made).[1]

Practical tip

Reassess the patient if they have a raised hs-cTn.

Troponin can be acutely raised due to other causes such as myocarditis, aortic dissection, or acute pulmonary embolism.[73]

Chronic elevation of high-sensitivity troponin is also common in patients with renal dysfunction and heart failure.[1][2]

Troponin levels may remain elevated for 1-2 weeks following recent myocardial infarction and/or percutaneous coronary intervention.

Interpret hs-cTn in the context of the clinical scenario.

Evidence: High-sensitivity troponin tests in early rule-out protocols

Use of high-sensitivity troponin allows for a rapid ‘rule-out’ of non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) using an accelerated diagnostic algorithm (e.g., high-sensitivity troponin at 0 and 1 hours).

The 2023 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guideline for the management of acute coronary syndromes recommends using a 0 and 1 hour rapid rule-out and rule-in protocol if a high-sensitivity troponin assay is available.[1] This recommendation was based on evidence of a reduced delay to diagnosis, which has been shown to decrease accident and emergency department stay and lower costs through identification of patients who can be discharged early and managed as outpatients. The second-best option was a 0 and 2 hour algorithm.

The very high safety and high efficacy of the ESC 0 and 1 hour algorithm has been confirmed in three real-life implementation studies (RAPID-CPU, High-STEACS, and RAPID-TnT), of which one, RAPID-TnT, was a randomised controlled trial.[78][79][80]

Both algorithms were developed in large derivation cohorts and then validated in large independent cohorts.

The guideline panel noted that these algorithms should always be integrated into a clinical pathway with clinical assessment and 12-lead ECG, and that repeat blood sampling is mandatory if the patient has ongoing or recurrent chest pain.

The ESC guideline panel selected optimal thresholds for rule-out to allow for a minimal sensitivity and negative predictive value for myocardial infarction of 99%, while optimal thresholds for rule-in allowed for a minimal positive predictive value for myocardial infarction of 70%.[1][81]

The 2015 ESC guideline had recommended a 0 and 3 hour algorithm. However, three subsequent large diagnostic studies suggested this algorithm performed less well in terms of efficacy and safety compared with more rapid protocols using lower rule-out concentrations.[79][82][83]

However, the 2023 guideline noted that with the rapid protocols the following patients may need additional cardiac troponin concentration at 3 hours:

If the first two hs-cTn measurements of the 0/1 algorithm are inconclusive and no alternative diagnoses explaining the condition have been made.

In 2020 the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published diagnostic guidance on the use of high-sensitivity troponin tests for the early rule-out of acute myocardial infarction in adults presenting with acute chest pain.[74]

Overall NICE concluded it is possible to rule out NSTEMI using a high-sensitivity troponin T or I assay if the levels are below the diagnostic threshold (99th percentile), or a threshold at or near the limit of detection of the assay, on arrival and at 30 minutes to 3 hours later. NICE recommended, in selected patients, that a single sample on presentation using a threshold at or near the limit of detection may be used to rule out NSTEMI.

The NICE recommendation was based on a systematic review and health economic analysis prepared by an external assessment group.[84]

NICE found no strong evidence to differentiate between high-sensitivity troponin tests, and when used in an early rule-out strategy all were cost-effective compared with the standard troponin assay. Therefore, NICE recommended a range of early rule-out strategies (both single and multiple sample) including the ESC 0 and 1 hour algorithm.

However, NICE did stipulate that further research is required to explore the optimal testing strategies for these assays in subgroups including sex, age, ethnicity, and renal function.

Chest x-ray

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends ordering a chest x-ray only if you suspect other diagnoses or to rule out complications of ACS.[73] However, in our expert’s opinion you should order a chest x-ray for all patients with acute chest pain to look for other causes such as pneumothorax or a widened mediastinum in aortic dissection, or complications of ACS such as pulmonary oedema due to heart failure.

Practical tip

Ensure an ECG is recorded and interpreted before considering a chest x-ray. If the ECG indicates STEMI, refer the patient immediately to cardiology for consideration of primary percutaneous coronary intervention to avoid the delay that may be associated with requesting a chest x-ray.

Full blood count

Check full blood count to evaluate:

Thrombocytopenia to estimate risk of bleeding; unstable angina treatment increases the risk of bleeding

Possible secondary causes of unstable angina (i.e., secondary blood loss, anaemia)

Anaemia is common in unstable angina and persistent or worsening anaemia in ACS is associated with increased mortality and major bleeding.[1]

Urea, electrolytes, and creatinine

Measure renal function to:

Determine serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate; these are key elements in assessing the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) risk score[1] [ GRACE Score for Acute Coronary Syndrome Prognosis Opens in new window ]

Determine the choice and dose of anticoagulant[1]

Prevent contrast-induced nephropathy if an invasive strategy is planned in a patient with chronic kidney disease.[1]

Be aware that a patient with chronic kidney disease may have a chronically raised troponin.[2] Patients with chronic kidney disease may also have electrolyte abnormalities that can cause ECG abnormalities.

Liver function tests

Measure liver function to include in the assessment of bleeding risk before starting anticoagulation.

Blood glucose

Check blood glucose in any patient with known diabetes or hyperglycaemia on admission to hospital regardless of a history of diabetes.[1]

Monitor blood glucose levels frequently if the patient has known diabetes or hyperglycaemia on admission.[1]

Manage hyperglycaemia in patients admitted with ACS by keeping blood glucose <11 mmol/L (<198 mg/dL) while avoiding hypoglycaemia.[71] See Management of hyperglycaemia under Management recommendations.

C-reactive protein (CRP)

NICE does not recommend using CRP to diagnose an ACS.[73] However, in our expert’s opinion, CRP is commonly ordered to rule out other causes of acute chest pain (e.g., pneumonia).

Lipid profile

Recommended for risk stratification. Target LDL <2.6 mmol/L (<100 mg/dL) if coronary artery disease present.

Coagulation profile

Recommended at baseline, as treatment options affect coagulation.

Consider in some patients

Echocardiography

Organise urgent echocardiography for any patient with signs of acute heart failure or haemodynamic instability or who is in cardiac arrest.[1] This should only be performed by those with consultant training.

Use a point-of-care transthoracic echocardiogram to:

Look for regional wall motion abnormalities of the left ventricle in patients with an atypical presentation or equivocal ECG.[1][2][85][86]

Look for mechanical complications of acute MI (see Acute MI complications - mechanical below):[86]

Left ventricular function

Right ventricular function

Ventricular septal rupture

Left ventricular free wall rupture

Acute mitral regurgitation

Pericardial effusion

Cardiac tamponade.

Suggest alternative aetiologies associated with chest pain (e.g., acute aortic disease, pulmonary embolism).[1][86]

A pre-discharge echocardiogram is indicated for all patients post-acute MI to assess left ventricular function after coronary reperfusion therapy and to guide prognostication.[71][87]

Invasive coronary angiography

Invasive coronary angiography (with or without revascularisation) may be considered by the cardiology team for a patient with suspected unstable angina (with a negative troponin test result) based on the risk assessment and clinical presentation.[71] Patients with unstable angina have a significantly lower risk of death compared with those with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction and get less benefit from an immediate invasive approach.[88] An inpatient invasive strategy (coronary angiography within 72 hours of admission, with follow-on percutaneous coronary intervention if indicated) is generally recommended for patients with a high index of suspicion for unstable angina, particularly for those who have an intermediate or higher risk of adverse cardiovascular events.[1][71]

Functional (stress) testing

Functional (stress) testing (e.g., stress echocardiography, perfusion/stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, myocardial perfusion scan) may be considered by the cardiology team as part of the initial work-up in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome but non-elevated (or inconclusive) high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn), no ECG changes, and no recurrence of pain.[1]

Coronary computed tomography angiography

Coronary computed tomography angiography may be considered by the cardiology team if the patient has no ischaemic changes on ECG and has been pain-free for several hours.[1]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer