Approach

Introduction

As an initial summary, we recommend the following key points when evaluating a patient with a thyroid mass:

Confirm whether the mass is intrathyroidal or extrathyroidal. Clues from the history, the physical examination, and imaging (ultrasound and/or CT) can help in differentiating between the two.

Cervical ultrasonography is the preferred initial test of choice for evaluating the structure and anatomical location of a neck mass, and for assessing the presence of features that may increase clinical suspicion about the mass.[2][38][33] It is cost-effective and does not expose the patient to ionising radiation.

Cervical lymph nodes should always be evaluated ultrasonographically when a thyroid nodule is being assessed.[1] If they have signs of malignancy (microcalcifications, cystic aspect, peripheral hypervascularity), ultrasound-guided needle aspiration biopsy should be performed.[1]

If the mass or nodule arises from the thyroid gland, assess whether the mass is hormonally active.[3] The history, physical examination, and paired free T4 and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) measurements are used to assess the functional status of the lesion.

Diffuse, non-nodular thyroid masses may be a result of thyroiditis or lymphoma and evaluation depends on the severity of symptoms, rate of progression, and sonographic appearance of the lesion.

Ultrasound features alone are not sufficient to exclude or confirm malignancy. For thyroid nodules that require definitive diagnosis, ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) should be performed when this knowledge would be clinically impactful. Appropriate subsequent management can be guided by cytology results. Current guidance discourages routine biopsy of thyroid nodules less than 1 cm.[1][2][18]

Diagnostic lobectomy (hemithyroidectomy) should be considered for definitive histological diagnosis following two or more unsatisfactory or indeterminate FNA biopsies; these patients have a higher risk of malignancy than the general rate for all thyroid nodules.[1]

The following sections explain the diagnostic approach in more detail.

History

Most thyroid nodules are asymptomatic. However, the patient should be evaluated for symptoms of hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism and for local compressive symptoms such as dysphonia, dysphagia, and dyspnoea.

Symptoms of hyperthyroidism include irritability, increased perspiration, heat intolerance, palpitations, tremors, anxiety, insomnia, fine brittle hair, frequent bowel movements, and weight loss. Symptoms of hypothyroidism include cold intolerance, constipation, weight gain, fatigue, and dry and itchy skin.

Factors that increase the likelihood of malignancy are the following:[39]

Male sex

Age at presentation <20 years or >60 years

History of rapid growth

Prior head and neck irradiation (therapeutic, industrial/occupational, or from environmental release from a nuclear accident)

Dysphonia/hoarseness

Familial history of medullary thyroid carcinoma, other thyroid cancer, multiple endocrine neoplasia, or Cowden's syndrome.

Physical examination

Physical examination involves performing a detailed assessment of the thyroid mass and any associated lymphadenopathy, evaluating whether the patient has signs of hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism and evaluating whether the surrounding structures (trachea and oesophagus) are compressed.

Examination must include inspection and palpation of the anterior and lateral aspects of the neck to assess for thyroid enlargement, presence of nodules, and lymphadenopathy. Asking the patient to swallow during palpation, which elevates the thyroid, can improve the palpation of the thyroid gland and detection of nodules. The signs of hyperthyroidism include tachycardia, arrhythmias, muscle wasting, tremor, brisk reflexes, and brittle hair. The signs of hypothyroidism include bradycardia, thickened and puffy appearance of skin (myxoedema), and delayed relaxation phase of reflexes.

Visualisation of vocal fold movement is very important if the patient presents with dysphonia. This can be done with a dental mirror and a headlight, an ultrasound examination, or with a flexible nasopharyngoscope (the definitive test).[40] A paralysed vocal cord ipsilateral to the thyroid mass is a concern for an invasive thyroid cancer. Current American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery guidelines recommend laryngeal examination for patients with a neck mass deemed at increased risk for malignancy.[41] This may involve referral to another clinician who is able to perform this targeted examination.

Physical characteristics of a thyroid nodule are poor predictors of malignancy; however, the following characteristics portend a higher risk of malignancy:[39]

Nodules >4 cm in size

Firmness on palpation

Fixation of the nodule to adjacent tissues

Cervical lymphadenopathy

Vocal cord paralysis

Examination findings of fibrosis, consistent with a history of ionising radiation to neck or upper chest.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: GoitreCourtesy of Mediscan/Alamy: used with permission [Citation ends].

Laboratory assessment

Patients presenting with thyroid nodules are usually euthyroid. This should be confirmed by a serum TSH level.[2][38] If the TSH is below normal (suppressed), further assessment with free thyroxine (FT4) and calculated or free triiodothyronine (FT3) should be performed to confirm hyperthyroidism. Some practitioners prefer to order TSH and FT4 as a paired set.

Consider asking patients about their biotin (vitamin B7) intake, as a high consumption from dietary supplements may lead to falsely high or low thyroid function test results.[38][42][43]

Hyperthyroidism in the setting of thyroid nodules may suggest the presence of one or more hyperfunctioning (autonomous) adenomas and the risk of malignancy in such nodules is very low.[2] If the thyroid is diffusely enlarged, Graves' disease or thyroiditis should be suspected. Radioactive iodine uptake and scan will typically differentiate between these conditions and should be withheld until FT4/TSH is first tested.[36] If the TSH is elevated, further assessment with FT4 and autoantibodies (with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis being considered) should be performed.

Serum calcium (total and ionised) and intact parathyroid hormone levels may be assessed if the imaging characteristics of the nodule or neck mass are suggestive of an enlarged parathyroid gland.[2] Serum calcitonin levels should be obtained in patients with a family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma and multiple endocrine neoplasia type II. However, checking calcitonin for the routine evaluation of thyroid nodules has not been routinely recommended.[1][34][44]

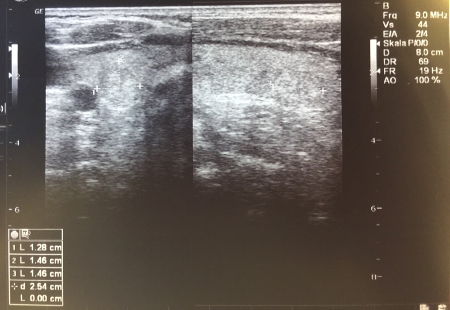

Ultrasonography

Cervical ultrasonography is the initial imaging study of choice for thyroid nodules as well as many other anatomical lesions in the neck.[33] Ultrasonography can detect and characterise nodules too small to be palpable, and provide exact dimensions to facilitate serial monitoring.[2] Ultrasonography is used extensively in the assessment of central or lateral neck lymphadenopathy.[2][34]

Frequently, inflammation (e.g., subacute thyroiditis, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and chronic thyroiditis) may lead to a heterogeneous echotexture of the thyroid gland that may, in conjunction with associated lymphadenopathy, be suggestive of the diagnosis. Inflammation may also lead to the formation of pseudonodules, which are indistinctly demarcated areas that arise due to focal heterogeneity but are not true nodular lesions. These lesions disappear on ultrasound when the transducer is turned 90 degrees to where the pseudonodule is visualised. Pseudonodules do not require FNA and in the setting of thyroiditis should be followed expectantly to see if they regress once the thyroiditis resolves.

Size and sonographic features of the nodule determine whether further evaluation with FNA is warranted.[35][45] Malignancy cannot be definitively diagnosed or excluded with ultrasonography. However, the presence of the ultrasonographic features noted below should raise the level of suspicion about malignancy and the need for FNA biopsy:[45]

Presence of a solid component

Microcalcifications

Irregular margins

Taller than wide shape

Hypoechoic sonographic appearance relative to thyroid parenchyma.

Threshold size for FNA depends on the sonographic characteristics, but usually exceeds 1 cm. FNA biopsy of smaller nodules should be considered if there is a high-risk history or suspicious sonographic appearance. Observation of some of these lesions may merit discussion between the physician and the patient in selected cases.

FNA biopsy of palpable and incidentally discovered solid thyroid nodules without high-risk history of sonographic features should be considered if the size is ≥1 cm. Mixed cystic and solid nodules with no suspicious features and spongiform nodules ≥2 cm should be evaluated with FNA.[1] A nodule that has been biopsied previously but has increased in size >50% on a follow-up study should also be considered for re-biopsy.[1]

All lymph nodes suspicious for locally metastatic thyroid cancer should be biopsied if that will change the treatment plan, as should lymph nodes in a location close to the trachea or carotid artery that may present a risk for complication if left untreated. However, in some circumstances, lymph nodes may just be observed.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nodule sonographic characteristics and threshold size for fine needle aspiration (FNA).Created by the BMJ Knowledge Centre and Dr B.C. Stack Jr; adapted from Haugen BR, Alexander EK et al. Thyroid 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ultrasound image of thyroid noduleCourtesy of Getty images; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ultrasound image of thyroid noduleCourtesy of Getty images; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: TI-RADS calculator: chart showing five categories on the basis of the ACR Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS) lexicon, TR levels, and criteria for fine-needle aspiration or follow-up ultrasoundAdapted from Tessler FN et al. J Am Coll Radiol 2017 May;14(5):587-95 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: TI-RADS calculator: chart showing five categories on the basis of the ACR Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS) lexicon, TR levels, and criteria for fine-needle aspiration or follow-up ultrasoundAdapted from Tessler FN et al. J Am Coll Radiol 2017 May;14(5):587-95 [Citation ends].

The American College of Radiology (ACR) Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS) lexicon categorises the ultrasound features as benign, minimally suspicious, moderately suspicious, or highly suspicious for malignancy. This helps guide the decision as to whether follow-up ultrasound or FNA is required.[45]

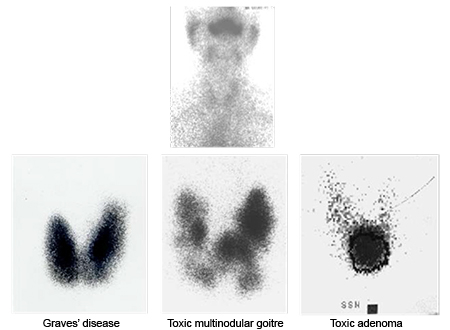

Radioisotope imaging

If TSH is suppressed, radioisotope imaging should be performed to identify autonomously hyperfunctioning ('hot') nodules and to distinguish between Graves' disease and thyroiditis. A thyroid nodule that exhibits focally increased radioisotope uptake with suppression of the surrounding thyroid parenchyma has a risk of malignancy of less than 2%.[3] A radioisotope scan showing such a 'hot' nodule obviates the need to perform FNA if there are no other suspicious features or history.[2] The use of radioisotope scanning for identification of 'cold' nodules as a means of risk stratification is no longer recommended because it does not offer additional advantages over ultrasound and FNA in differentiating malignant from benign lesions.[46]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Iodine uptake scans: typical appearances of absent uptake in thyroiditis (top panel); diffuse increased uptake in Grave’s disease (lower left panel); areas of increased and decreased uptake in toxic multinodular goitre (lower middle panel); single area of increased uptake in a toxic adenoma (lower right panel)Courtesy of Dr Petros Perros [Citation ends].

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Neither CT nor MRI (cross-sectional imaging) has a primary role in the initial evaluation of a thyroid nodule; however, they can be used for accurate measurement and assessment of the size of large substernal goitres and they may identify lymph nodes that cannot be visualised by ultrasound.[2] They are also helpful in cases of large goiters with posterior extension and diffuse bulky adenopathy.

Administration of iodinated contrast for CT scanning should be carefully considered because it often prevents subsequent diagnostic and therapeutic use of radioactive iodine for 4 to 8 weeks or longer. Iodinated contrast can also induce the Jod-Basedow effect (iodine-induced hyperthyroidism) and exacerbate hyperthyroidism in the presence of underlying Graves' disease or toxic adenoma(s). If there is concern about therapeutic use of radioactive iodine following administration of iodinated contrast for CT, a 24-hour urine collection can be performed and urine iodine measured.

Positron emission tomography (PET)

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET scans appear to have relatively high sensitivity but low specificity for malignancy, and results vary.[47] Therefore, FDG-PET is not recommended during the initial evaluation of a nodule. However, any FDG-avid thyroid nodule found incidentally deserves a thorough evaluation for malignancy.[48][49][50] The evaluation should include neck ultrasonography followed by FNA if indicated, based on patient's history and the nodule imaging characteristics.[51] Homogeneous diffuse PET uptake by the thyroid gland rarely indicates thyroid cancer: it is usually seen in chronic lymphocytic (Hashimoto's) thyroiditis.[36]

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy

Following ultrasonography, ultrasound-guided FNA is the procedure of choice for evaluation of suspicious thyroid nodules.[34] Cytology and adjunctive molecular genetic testing may determine whether surgery is indicated. The procedure is well tolerated and carries a very low risk of complications. Local pain and haematoma are the most common complications, while serious adverse events are rare.[52] FNA allows for improved diagnostic accuracy, a higher malignancy yield at the time of surgery, and significant cost reductions.[53] Use of ultrasound guidance for needle localisation has been shown to decrease the rate of inadequate specimens compared with unguided FNA.[54]

High-quality cytology smears are essential for diagnosis and must be technically adequate with well-prepared cellular material and colloid for a satisfactory evaluation. Cytopathology from the FNA is reported as either unsatisfactory, benign, indeterminate, suspicious, or malignant. Approximately 10% to 20% of cytology results are reported as unsatisfactory or inadequate, 60% to 75% are reported as benign, and 6% to 10% are reported as suspicious or malignant.[55][56] The exact terminology varies among pathology departments. This prompted the development of the Bethesda classification system, which is commonly used, and was updated in 2017. The Bethesda classification system includes recommended diagnostic categories, implied risk of malignancy, and recommended clinical management. The categories are designated as: non-diagnostic or unsatisfactory; benign; atypia of undetermined significance or follicular lesion of undetermined significance; follicular neoplasm or suspicious for a follicular neoplasm; suspicious for malignancy; and malignant.[57] Actual management may depend on other factors (e.g., clinical, sonographic) besides the FNA interpretation.[57][58]

Unsatisfactory cytology results require repeat FNA. A second attempt at ultrasound-guided FNA will produce a satisfactory diagnostic specimen in up to 75% of solid nodules and 50% of cystic nodules.[59] If the results are still unsatisfactory after 2 attempts, consideration should be given to observation or a diagnostic lobectomy (hemithyroidectomy).

Cytologically benign, non-cystic lesions on FNA may still have up to a 5% risk of malignancy that may be even higher in nodules ≥4 cm (probably from sampling error). Such nodules therefore still require follow-up with annual neck examination and neck ultrasonography.[60]

Aspirated cyst contents often produce cytological results interpreted as inadequate or indeterminate because of the lack of cellular content and absence of colloid. Most cystic nodules are complex (solid-cystic). Pure cysts do not generally need FNA unless symptomatic, because the risk of malignancy is extremely low, but where an unsatisfactory or indeterminate cytological aspirate is obtained from a pure cyst it may be managed conservatively and further intervention is not usually required.

Nodules with a Bethesda criteria cytological diagnosis of atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance or equivalent may be considered for repeat FNA after 4 to 6 weeks to allow for healing of the previous FNA tract.[61] Patients with follicular neoplasms suspicious for malignancy or malignant cytology should be referred to an experienced endocrine or head and neck surgeon for further management.

Classification systems are also available from the American Thyroid Association and the British Thyroid Association and map to the Bethesda categories.[1][62]

Use of molecular markers with FNA

Well-described point mutations, such as BRAF V600E, NRAS61, HRAS61, KRAS12/13, and RET/PTC and PAX8/PPARγ rearrangements, have been associated with thyroid cancer. The emerging use of molecular testing to assist in interpretation of FNA samples has been shown to increase the diagnostic accuracy and yield of the cytology results.[63]

When available, molecular testing is especially helpful in the evaluation of indeterminate cytology results where the presence of one of the above-noted mutations or rearrangements significantly increases the likelihood of malignancy.[57][64] The presence of a positive molecular test may, therefore, alter medical decision making in favour of upfront thyroidectomy as the most appropriate treatment choice. However, while most papillary and follicular thyroid cancers contain one of these mutations, the absence of a mutation cannot exclude malignancy.[1] If molecular testing is not available, a standard diagnostic approach typically involving diagnostic lobectomy (hemithyroidectomy) to resolve cytologically ambiguous or indeterminate cases is necessary.

Surgical diagnosis

Diagnostic lobectomy (hemithyroidectomy) should be considered for definitive histological diagnosis following two or more unsatisfactory or indeterminate FNA biopsies; these patients have a higher risk of malignancy than the general rate for all thyroid nodules.[1] Total thyroidectomy is recommended for some patients with malignant cytology depending on lesion size, lymphadenopathy, anticipated need for post-operative radioiodine, and other co-existing thyroid nodular disease.[1]

Nodules with indeterminate or suspicious cytology results should undergo a multidisciplinary evaluation by a surgeon and endocrinologist to determine optimal next steps.

Surgery is also indicated if a nodule is symptomatic because of compression of nearby structures such as the trachea or oesophagus. CT, MRI, and loop spirometry may be useful adjunctive methods for evaluation of the degree of compression. Removal of nodules of 4 cm or larger is recommended because the false-negative rate of FNA for detection of malignancy has been reported to be 13% from sampling error.[65] However, FNA may still be useful in evaluation of large nodules because pre-operative confirmation of malignant or suspicious cytology will enable optimal planning for the extent of surgery.

All patients undergoing thyroid surgery should have a pre-operative voice assessment; a pre-operative laryngeal examination is recommended for patients with pre-operative voice abnormalities.[1][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Algorithm for the evaluation of a thyroid massCreated by the BMJ Knowledge Centre and Dr B.C. Stack Jr (FNA, fine needle aspiration; PTH, parathyroid hormone; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone) [Citation ends].

Risk stratification

The concept of risk stratification of patients presenting with thyroid nodules that end in a malignant cytological diagnosis is key to understanding the management approach for thyroid cancer.[1][18][66] This can be achieved with pre-operative imaging or with additional data from post-operative pathology.[45] This process serves as an objective way of prescribing the level of vigilance and extent of surgical resection or ablation to patients with thyroid cancer, and has been illustrated based upon an escalating scale of known risks.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer