Approach

Do not wait for diagnostic test results if you suspect plague. Never delay or withhold treatment pending test results. The decision to initiate antibiotic therapy should be based on clinical signs and symptoms and the patient history (e.g., recent flea bite, exposure to areas with rodents, contact with a sick or dead animal).[26] Timely, appropriate antibiotic therapy reduces mortality.

Yersinia infection is a notifiable disease in most countries. Diagnosis may be suggested by characteristic clinical findings together with a history of potential exposure in an endemic area. Plague is a potential biological weapon, and cases of pneumonic plague occurring outside endemic areas should raise suspicion of accidental or deliberate release of aerosolised Yersinia pestis. Yersiniosis is generally self-limiting but invasive disease may occur.

Clinical presentation

Plague

The classic presentation in humans is bubonic plague, in which patients present with sudden onset of fever, malaise, prostrations, and painful swelling of lymph nodes possibly with necrotic areas (buboes) draining the bitten area. Fever is almost always present.[27]

Patients with septicaemic plague also present with systemic features but without clinically detectable lymph node involvement. They may present with meningeal symptoms.

Primary pneumonic plague has a short incubation period (from a few hours to 2-3 days). The onset of symptoms is rapid and may include pleuritic chest pain, haemoptysis, and dyspnoea. Secondary pneumonic plague results from systemic infection and develops in a few patients. Patients with signs of pneumonic plague should be isolated immediately and placed on droplet precautions.

Plague meningitis typically occurs as a complication of delayed or inadequate treatment of another clinical form of primary plague and is characterised by fever, nuchal rigidity, and confusion.

Patients with pharyngeal plague may present with pharyngeal inflammation and inflamed anterior cervical nodes; however, this form is uncommon.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Axillary buboFrom the image collection of the CDC; used with permission [Citation ends].

Yersiniosis

Enterocolitis is the most common syndrome of Yersinia enterocolitica infection in young children and may cause bloody stools. Older children may develop terminal ileitis and mesenteric adenitis, and the clinical presentation may be indistinguishable from acute appendicitis. Adults generally present with diarrhoea and abdominal pain, which may last for ≥3 weeks. Invasive infection is more likely to occur in patients with diabetes, chronic liver disease, alcoholism, or iron-overload syndromes.[4]

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection most commonly causes mesenteric adenitis. Enteritis is infrequent. Invasive infection is not common but may be seen in patients with chronic liver disease or haemochromatosis.[3]

Initial investigations

Plague is potentially hazardous to laboratory staff and must be handled in a biosafety cabinet. Laboratories must be made aware if samples potentially contain plague.

Microbiological testing for plague

Blood cultures should be sent together with other appropriate clinical samples, ideally before antibiotics are given; however, treatment should not be delayed. Appropriate samples may include bubo aspirates (bubonic plague), sputum or bronchial/tracheal washing (pneumonic plague), a throat swab specimen (pharyngeal plague), and cerebrospinal fluid if meningeal symptoms are present (septicaemic plague).[26][28] Buboes are typically solid, and aspiration may require saline to be injected into the bubo and immediately re-aspirated.

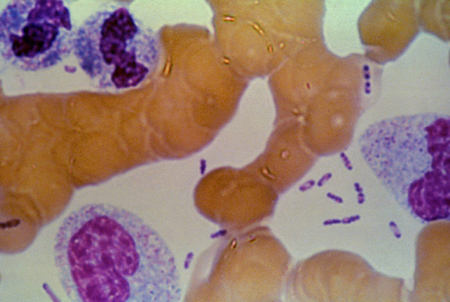

Clinical samples should be examined with Gram and Wright-Giemsa or Wayson stains and cultured in broth or on blood agar. Y pestis appears as gram-negative coccobacilli and as a light-blue bacillus with dark-blue polar bodies on Wright-Giemsa or Wayson stain. This 'safety pin' appearance is suggestive, but not pathognomonic, of plague but gives a rapid presumptive diagnosis.[26][28]

Reference laboratories use a specific bacteriophage to distinguish Y pestis from other Yersinia species.[29] Plague bacilli grow slowly, forming tiny colonies on blood agar at 24 hours, and are relatively inactive on biochemical testing. They express a unique envelope antigen (F1 antigen), and this is the target for a specific fluorescent antibody test.[28][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bipolar appearance with Wright stainFrom the image collection of the CDC; used with permission [Citation ends].

Microbiological testing for yersiniosis

Y enterocolitica and Y pseudotuberculosis can be isolated from clinical specimens such as stool on MacConkey agar. Cefsulodin-irgasan-novobiocin agar incubated at room temperature can be used as a selective agar if yersiniosis is suspected.[30]

Rapid antigen tests for plague

A rapid diagnostic test against the F1 antigen is available and is widely used in countries such as Africa and South America. A positive test is considered presumptive evidence of plague.[28]

The test is performed on sputum from patients with suspected pneumonic plague, or bubo aspirate from patients with suspected bubonic plague. The result is usually available within 15 minutes and is easy to interpret.[1]

These tests appear to be sensitive when compared to culture but poor specificity means false positive results are possible. The quality of evidence supporting the use of rapid diagnostic tests is low and culture is still necessary for diagnosis, as well as providing information on antimicrobial resistance and prevalent strains.[31]

The World Health Organization recommends using F1 rapid diagnostic tests in the following circumstances:[1]

People with suspected pneumonic or bubonic plague in endemic areas in order to rapidly detect disease and implement an immediate public health response (confirmatory testing is required before declaring an outbreak)

People with suspected pneumonic or bubonic plague during an outbreak to provide rapid diagnosis at the point of care (a confirmatory test should be carried out at the same time).

Other laboratory or imaging tests

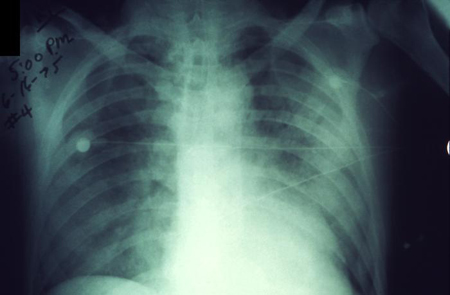

Routine tests are not specific enough to diagnose plague. White blood cell count is usually elevated 10,000 to 20,000 cells/mm³. There may be evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation. On a chest x-ray, pneumonic plague may appear as either unilateral or bilateral consolidation or alveolar infiltrates. Pleural effusion and hilar/mediastinal adenopathy have also been described.[32][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plague infection involving both lung fieldsFrom the image collection of the CDC; used with permission [Citation ends].

Subsequent investigations

Serological testing

Recommended for confirmation of diagnosis of plague, particularly if cultures are negative and plague is still suspected.[26][28] Acute and convalescent sera can be tested for antibodies to the F1 antigen of Y pestis by passive haemagglutination. Convalescent serum should be taken 4-6 weeks after disease onset. A fourfold increase between acute and convalescent titres is considered diagnostic.[26][28]

Serology testing for Y enterocolitica and Y pseudotuberculosis is used in Europe. Results may be difficult to interpret because of relatively high seropositivity in the general population and cross-reactivity with Salmonella, Brucella, and Rickettsia species.[33]

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer