Approach

Elevation of liver tests can be seen during biochemical investigations for suspected or known liver disease. Alternatively, abnormalities may be incidentally noted. The clinical presentation of patients with liver dysfunction may vary from no symptoms to multiple symptoms (e.g., due to the various complications of cirrhosis). The pattern of liver chemistry studies may reflect the probable aetiology, and history and examination can be tailored to them. However, in view of overlap of presentation of different diseases, it is prudent to consider other causes of liver test abnormalities until a definitive diagnosis is achieved.

In adults, a standard liver aetiology screen should include abdominal ultrasound scan, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C antibody (with follow-on polymerase chain reaction if positive), anti-mitochondrial antibody, anti-smooth, muscle antibody, anti-nuclear antibody, serum immunoglobulins, simultaneous serum ferritin, and transferrin saturation.[53] [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Possible diagnosis for underlying cause of different patterns of liver test abnormalitiesCreated by the BMJ Group [Citation ends].

Predominantly hepatocellular pattern

The liver injury predominantly affects hepatocytes, causing an elevation of aminotransferases (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine aminotransferase [ALT]). ALT is a cytosolic enzyme. AST is a mitochondrial (80%) and cytosolic (20%) enzyme, which is also present in heart, skeletal muscle, kidney, brain, and red blood cells (RBCs). ALT is a more specific marker of hepatic injury than AST.[3] Rapid hepatocellular injury could result in deteriorating functional capacity of the liver (acute liver failure).

Predominantly cholestatic pattern

The pattern of abnormality is a predominant elevation of alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Diseases associated with a cholestatic pattern predominantly affect the hepatobiliary system. ALP is a canalicular enzyme, which is also present in bone, intestine, and placenta. A cholestatic pattern is seen in patients with primary biliary cholangitis or primary sclerosing cholangitis, and in intra- or extrahepatic cholestatic diseases, including cholelithiasis, cholangiocarcinomas, and pancreatic malignancies.

When all liver tests are normal except for elevated ALP, the following tests may help determine whether the abnormality is due to liver dysfunction.

Gamma glutamyl transferase (gamma-GT): this enzyme catalyses the transfer of the gamma-glutamyl group from peptides to other amino acids. It is clinically useful only in cases where there is an isolated elevation of ALP. In this scenario, an elevated gamma-GT confirms that the elevated ALP is of hepatic origin.[3]

5'-nucleotidase: this is present in liver associated with canalicular and sinusoidal plasma membranes, and is also present in the intestines, brain, heart, RBCs, and endocrine pancreas. It is clinically useful only in cases where there is an isolated elevation of ALP.

Predominantly infiltrative pattern

Focal or diffuse infiltration of the liver produces abnormal liver tests in an infiltrative pattern as follows:

ALP is elevated

ALT and AST are frequently normal or minimally elevated

Bilirubin elevation is a late manifestation.

Liver test abnormalities in infiltrative disorders are quite similar to those seen with a cholestatic pattern. Conditions causing this pattern of changes include granulomatous and infiltrative diseases such as tuberculosis (TB) and lymphomas.

Bilirubin elevation

Bilirubin occurs in two forms:

Conjugated bilirubin (also called direct-reacting bilirubin)

Unconjugated form (also called indirect-reacting bilirubin).

Unconjugated bilirubin elevation usually occurs when production of bilirubin is increased by breakdown of cells (e.g., RBCs), haemoglobin, or myoglobin, which is beyond the capacity of liver conjugation. This pattern is seen in certain congenital diseases (e.g., Gilbert's syndrome, sickle cell anaemia, haemoglobinopathies) and other causes of haemolysis.

Predominantly, conjugated bilirubin elevation occurs due to liver disease and biliary disease when the flow of bilirubin is obstructed.[3] This pattern of bilirubin elevation can be seen in primary sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cholangitis, HIV cholangiopathy, infiltrative liver disease (intrahepatic cholestasis), extrahepatic obstructions (e.g., cholelithiasis, choledocholithiasis, cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic malignancies, and other obstructions of biliary systems), and advanced chronic liver disease with cirrhosis and liver failure.[4]

Cirrhosis

It is not possible to differentiate cirrhosis by patterns of liver test abnormalities. Patients with cirrhosis may have a hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed pattern of liver test abnormality, or may have normal liver tests.

The presence of thrombocytopenia (platelet count <150,000/microlitre) is the most sensitive and specific laboratory finding for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in the setting of chronic liver disease and results from portal hypertension with hypersplenism and platelet sequestration.[54] Liver biopsy remains the most specific and sensitive test for the diagnosis of cirrhosis. In addition to confirming the diagnosis, liver biopsy may help to determine the aetiology of the underlying liver disease, although this is not always possible. Liver biopsy is not necessary in patients with advanced liver disease and typical clinical, laboratory, and/or radiological findings of cirrhosis, unless there is a need to determine the degree of inflammation.

Serological and indirect markers of fibrosis have a good negative predictive value for cirrhosis, and are often used in community settings to risk stratify patients with risk factors for liver disease. These non-invasive of liver elasticity include serum markers such as the AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) or fibrosis-4 score (Fib-4) and imaging techniques (transient elastography, acoustic radiation force impulse imaging).[55][56][57]

In adults with chronic liver disease, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends against using the currently available serum markers or thrombocytopenia alone for the detection of clinically significant portal hypertension; rather they suggest using a combination of non-invasive imaging techniques and platelet count.[58]

Non-hepatic causes of abnormal liver tests

Possible non-hepatic sources should be considered.

Bilirubin elevation: the source may be RBCs (e.g., with haemolysis, intra-abdominal bleeds, or haematomas). The most common cause of mild bilirubin elevation is Gilbert's syndrome. In this condition, the other liver tests are normal and ≥90% of bilirubin is unconjugated. Gilbert's syndrome is not a disease but rather a physiological variant and is entirely benign.

AST: the source may be skeletal or cardiac muscle.

ALP: the source may be bone, placenta, kidney, or intestines. Elevated ALP may be physiological during the third trimester of pregnancy.[6]

Gamma-GT: the source may be the heart or RBCs.

History

A focused history, eliciting the risk factors related to various aetiologies of liver disease, should be obtained. Specific questioning may be directed toward the suspected cause, based on the duration and pattern of liver test abnormality seen. General symptoms detected from the history that may be associated with various patterns of liver test abnormalities include:

Fatigue

Anorexia

Pruritus

Weight loss

Nausea and vomiting

Right upper quadrant pain

Fever (may be a misinterpreted sign in acute alcoholic hepatitis)

Abdominal distension

Leg swelling

Haematemesis or melaena.

Questions to specifically consider in a patient with a hepatocellular pattern of liver test abnormality may include the following.

The amount of alcohol used. CAGE (an acronym of the four questions in the questionnaire) and AUDIT-C (alcohol use disorders identification test) scores help in assessing the risk for alcohol misuse (increasing with higher scores). An AUDIT-C test has a higher sensitivity and specificity than CAGE questions in diagnosing potential alcohol use disorder.[59] The Center for Quality Assessment and Improvement in Mental Health: AUDIT-C overview Opens in new window Although the CAGE score and AUDIT-C tool are helpful resources, it is important to remember that not all people with alcohol use disorder have liver disease. The four questions that make up the CAGE score are:[60]

C: Have you ever felt you needed to CUT down on your drinking?

A: Have people ANNOYED you by criticising your drinking?

G: Have you ever felt GUILTY about drinking?

E: Have you ever felt you needed a drink first thing in the morning ('EYE-OPENER') to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover?

The presence of risk factors for viral hepatitis infection, including history or presence of travel abroad, blood and blood products transfusion, recreational drug usage, high-risk sexual exposure, tattoos, body piercings, needlestick exposures, scarifications, close contact with people known to have viral hepatitis, or known community outbreaks.

Specific features of other infections, such as sore throat and lymphadenopathy with cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infection; night sweats with HIV or TB infection.

Other past medical history and family history.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) should be considered in people with risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, cardiac disease, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, sleep apnoea, or a family history of MASLD, in the absence of excessive alcohol intake (<112 g or 14 units/week). Lean MASLD should be diagnosed in people with MASLD and body mass index <25 kg/m² (non-Asian) or body mass index <23 kg/m² (Asian).[29][32]

The presence of autoimmune diseases and/or a positive family history of autoimmune disease may suggest autoimmune hepatitis as a cause.

A history of a condition that may be associated with hypotensive episodes, such as recent anaesthesia or surgery, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, sepsis, haemorrhage, or a risk factor for venous thrombosis, may indicate a condition with a cardiovascular aetiology.

A family history of a condition associated with liver dysfunction, joint and cardiac symptoms, diabetes mellitus (e.g., with haemochromatosis), neurological symptoms (e.g., with Wilson's disease), or respiratory symptoms (e.g., with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency) may indicate a hereditary cause.

Current pregnancy. Pregnancy-related liver dysfunction (e.g., intrahepatic cholestasis; acute fatty liver of pregnancy; or haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets [HELLP] syndrome) should also be considered.

Drug and medication history including exposure to toxins, all prescription and non-prescription medications, their dosage, and duration of use. The history should cover any medication, herbal or dietary supplements taken within 180 days before presentation, due to occasional long latency intervals between ingestion and liver injury.[20] It is important to enquire about a history of herbal and dietary supplements.[20] Paracetamol overdose is the most common cause of acute liver failure in the UK and US.[61][62]

Questions to specifically consider in a patient with a cholestatic and infiltrative pattern of liver test abnormality may include the following.

Presence of pain. Usually present with mechanical obstruction of the cystic duct or common bile duct, particularly when the obstruction is acute (e.g., a common duct stone) or there is an associated infection (ascending cholangitis). Pain can be absent in extrahepatic malignancies; biliary and pancreatic cancer is frequently painless.

Age. Primary biliary cholangitis typically presents in middle-aged women and is often asymptomatic. Abdominal pain may occur, but is most commonly absent.

Specific features of tuberculosis (e.g., fever, night sweats, weight loss), which may cause this pattern of liver test abnormality.

Past medical history. There may be a history of inflammatory bowel disease, particularly ulcerative colitis, with primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Current pregnancy. Pregnancy-related liver dysfunction should be considered in the history.

Drug and medication history, herbal supplement use, and history of exposure to toxins. Various drug treatments may cause this pattern of abnormality.

Physical examination

A complete physical examination is necessary, including measurement of vital signs, brief assessment of mental state, and level of consciousness. A rapid deterioration in mental status may indicate acute liver failure, sepsis, or shock.

Important specific features to note during general physical examination include:

Needle marks or tattoos (viral hepatitis B and C, and HIV infection)

Dupuytren's contractures, spider angiomas ('spider naevi' or telangiectasias) [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Dupuytren's contractureFrom the collection of Craig M. Rodner, MD, University of Connecticut Health Center/New England Musculoskeletal Institute, CT [Citation ends].

Skin discoloration, joint swelling, signs of diabetes mellitus and/or cardiac disease (haemochromatosis)

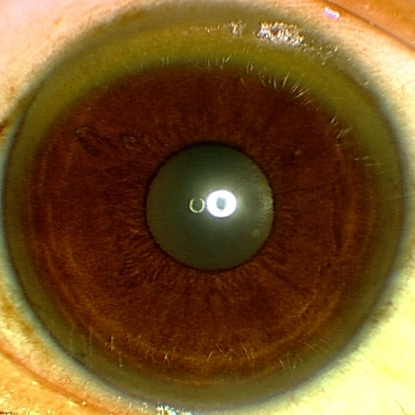

Kayser-Fleischer ring on eye examination. Patients with liver dysfunction due to Wilson's disease may have Kayser-Fleischer rings, as copper usually accumulates in the eye first. A slit-lamp examination may be required to assess for this finding[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Eye demonstrating Kayser-Fleischer ringAdapted from BMJ (2009), used with permission; copyright 2009 by the BMJ Publishing Group [Citation ends].

Xanthelasma, tendon xanthomas, skin pigmentation (primary biliary cholangitis)

Obesity, hypertension, xanthomas, xanthelasma, and arcus senilis; or acanthosis nigricans and diabetic ulcers (MASLD)[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Acanthosis nigricans involving the axilla of an obese white womanFrom the collection of Melvin Chiu, MD, UCLA [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plantar ulcer in a patient with type 1 diabetesFrom the collection of Rodica Pop-Busui, MD, PhD, University of Michigan, MI [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plantar ulcer in a patient with type 1 diabetesFrom the collection of Rodica Pop-Busui, MD, PhD, University of Michigan, MI [Citation ends].

Signs of infection (e.g., rash, fever)

Pregnancy, which in the presence of HELLP syndrome may be associated with hypertension, oedema, and brisk reflexes.

Other signs that may be found in people with chronic liver disease include:

Skin changes: palmar erythema, spider angiomas, petechiae, jaundice (when jaundice is present, there may be skin excoriations from scratching pruritic skin)

Head and neck: parotid swelling

Abdomen: abdominal distention, prominent abdominal veins, flank fullness and dullness, ascites, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly (if the liver is palpable, it is important to palpate for a tumour mass)

General: muscle wasting, gynaecomastia, pedal and ankle oedema

Signs of increased bleeding tendency, such as ecchymoses.

Hepatic encephalopathy, which may occur in acute liver failure or decompensated cirrhosis with portal hypertension, may be graded using the West Haven criteria as follows.[63][64]

Minimal (covert): psychometric or neuropsychological alterations of tests exploring psychomotor speed/executive functions or neurophysiological alterations without clinical evidence of mental change

Grade 1 (covert): trivial lack of awareness, euphoria or anxiety, shortened attention span, impairment of addition or subtraction, altered sleep rhythm

Grade 2 (overt): lethargy or apathy, disorientation for time, obvious personality change, inappropriate behaviour, dyspraxia, asterixis

Grade 3 (overt): somnolence to semi-stupor, responsive to stimuli, confused, gross disorientation, bizarre behaviour

Grade 4 (overt): coma.

Tests: hepatocellular pattern with acute liver failure

Further investigations following the discovery of an abnormality on blood liver tests are based on the pattern of abnormality noted, clinical history, and physical examination findings. Acute liver failure is characterised by rapid-onset, progressive symptoms (onset of encephalopathy, coagulopathy, and possibly jaundice) and evidence of a hepatocellular pattern of liver injury (acute elevation of aminotransferases) in the absence of known underlying liver disease.

Conditions responsible for acute liver failure with a hepatocellular pattern of abnormality on liver tests include:

Drugs and other toxins (e.g., paracetamol poisoning)

Viral hepatitis (e.g., hepatitis A, B, or E)

Autoimmune hepatitis

Vascular causes (e.g., Budd-Chiari syndrome [hepatic outflow tract obstruction], shock liver [ischaemic hepatitis])

Wilson's disease

Pregnancy-related liver injuries.

These patients should be evaluated for coagulopathy (prothrombin time and international normalised ratio [INR]), metabolic changes (arterial pH and lactate), and renal function (urea and serum creatinine).

Other tests that may be helpful during initial evaluation include:

FBC

Drug and toxicology screen (with a history of or suspected drug overdose)

Paracetamol level (with a history of or suspected drug overdose). This should be checked 4 hours after ingestion, or as soon as possible in patients presenting after the 4-hour period. The combination of time after the overdose and level provides a guide to evaluating hepatotoxicity. FDA: acetylcysteine/interpretation of acetaminophen assays Opens in new window However, in repeated supratherapeutic overdose, paracetamol levels may be low or undetectable: this should not preclude initiation of acetylcysteine in suspected cases of overdose. These cases are challenging and discussion with a toxicologist is strongly advised.

Salicylate levels (with a history of or suspected drug overdose if unable to rule out salicylate overdose).

Hepatitis viral antibodies (particularly if there are risk factors for hepatitis infection). Laboratory assessment for acute disease includes antibody to hepatitis A IgM (for hepatitis A), antibody to hepatitis B core IgM (for hepatitis B), antibody to hepatitis E IgM (for hepatitis E), and a nucleic acid amplification test for hepatitis C RNA (for hepatitis C, although presentations with acute hepatitis C are very uncommon). Additional viral serologies may be considered, including cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and herpes simplex virus.

Auto-antibodies and serum quantitative IgG levels (if considering autoimmune hepatitis).

Levels of ALP are frequently normal or low relative to bilirubin in people with Wilson's disease, such that an ALP:bilirubin ratio of <4 has a high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing acute liver failure secondary to Wilson's disease.[65]

Imaging studies such as abdominal ultrasound scan with Doppler or contrasted computed tomography (CT) scan (choice of test is based on body habitus, presence of other comorbidities, and clinical and biochemical parameters required to evaluate the liver adequately).[66] Imaging to assess hepatic vasculature is essential to diagnose Budd-Chiari syndrome.

CT imaging of the head should be considered in patients presenting with altered mentation indicating onset of encephalopathy.

Liver biopsy (not always necessary, but in some conditions confirms the diagnosis, such as autoimmune hepatitis, pregnancy-related intrahepatic cholestasis, acute fatty liver of pregnancy). In the setting of severe hepatic dysfunction, a transvenous approach for liver biopsy may be preferred, particularly in patients with coagulopathy, ascites, or increased bleeding risk. In the presence of coagulopathy, the need for liver biopsy and the approach used should be carefully considered based on the risk and the diagnostic need for the procedure.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (if there is evidence of acute bleeding, possibly due to oesophageal varices).

Tests: hepatocellular pattern without acute liver failure

When AST and ALT elevations are predominant, and the condition is not acute liver failure, the following conditions are considered as possible diagnoses:

Acute or chronic alcohol-related liver disease

MASLD

Viral hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis

Haemochromatosis

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

Wilson's disease

Drug-induced liver injury.

Investigations to consider include:

INR. Elevated INR may indicate a decline in hepatic synthetic function due to parenchymal liver disease, but may also be present in people with alcohol-related liver disease as a result of dietary vitamin K deficiency.

Bilirubin level and prothrombin time. The degree of bilirubin elevation and prothrombin time prolongation help gauge the severity of acute alcoholic hepatitis.

Ratio of AST to ALT. A ratio of >2:1 suggests alcohol-related liver disease. This ratio also underpins a number of simple non-invasive algorithms used to stratify disease severity in chronic liver diseases, such as the AST to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) score, the Fib-4 score, and the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score.[67][68][69][70] [ NAFLD Fibrosis Score Opens in new window ]

Degree of elevation of aminotransferases or ALP change. People with chronic alcohol-related liver disease, including those with severe acute alcoholic hepatitis, typically have a modest elevation of AST and ALT (AST <400 units/L, with relatively mild elevations in ALT). Levels of ALP are frequently normal or low in people with Wilson's disease.

Hepatitis viral serology (particularly if there are risk factors for hepatitis infection).

Specific blood tests for other suspected infections (e.g., HIV, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus).

Copper studies

Serum ceruloplasmin: elevated in many liver diseases as an acute-phase reactant, but low or low-normal in people with cirrhosis and poor hepatic synthetic function or in those with Wilson's disease.

24-hour urine copper: usually elevated in Wilson's disease.

Serum copper: usually reduced in people with Wilson's disease, due to depressed copper-carrying protein (ceruloplasmin). Serum copper may be normal or elevated in patients with Wilson's disease with liver injury.[71]

Phenotypic markers of iron overload (serum iron, total iron binding capacity, serum ferritin, serum transferrin saturation, and/or hepatic iron concentration). This should be part of the evaluation of nearly every patient with chronically abnormal liver tests. Elevated transferrin saturation ≥45% can be used as an initial screening test with high sensitivity in cases of suspected hereditary haemochromatosis.[72] If transferrin saturation is ≥45%, and serum ferritin is elevated, gene testing should be performed. Higher levels of serum ferritin increase the likelihood of fibrosis in patients with haemochromatosis.[38] Serum ferritin may be elevated in the absence of iron overload in acute liver injury of any type because ferritin is an acute-phase reactant.

Genetic tests

When iron overload is confirmed, genetic causes need to be considered, especially hereditary haemochromatosis (HFE) proteins. Hereditary haemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disease: two abnormal alleles are present (C282Y-C282Y; or C282Y-H63D). If the index case has one of these genotypes, relatives are screened.[38][72] Many patients with haemochromatosis do not have aberrant HFE proteins, and not all with HFE proteins have (or will develop) iron overload.

If the diagnosis of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is considered (e.g., in patients with a family history, or with liver or lung disease in patients aged <40 years), determining the protease inhibitor phenotype (Pi) is superior to measuring total serum alpha-1 antitrypsin levels. The usual Pi MM phenotype is replaced, most often by the ZZ phenotype, sometimes by others. Although two aberrant alleles are usually required for expression of disease, the MZ phenotype may be associated with otherwise unexplained liver disease and an increased risk of cirrhosis in the setting of other chronic liver diseases (such as MASLD).

Anti-smooth muscle antibody, antinuclear antibody, and serum immunoglobulins for suspected autoimmune hepatitis.[73]

Upper endoscopy to evaluate for varices. This may be performed in people with chronic liver diseases, either as an urgent test if the patient presents with melaena or haematemesis, or as a screening test in the presence of cirrhosis of any cause.

Liver biopsy

May be required to establish a diagnosis if this is not apparent on clinical assessment and a screen of tests for viral, metabolic, and autoimmune causes.

Often required to establish the diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and to stage the severity of hepatic fibrosis.[29]

Usually required to diagnose autoimmune hepatitis.

May help stage disease severity in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis with a serum ferritin of >2247 picomols/L (>1000 nanograms/mL), or with abnormal iron indices without HFE C282Y homozygosity, particularly with concomitant risk factors such as excessive alcohol intake, obesity, or diabetes, to assess for evidence of liver iron overload or fibrotic liver disease.[38][72]

May not always be required in other conditions (e.g., viral hepatitis) but may prove helpful after diagnosis, to stage the level of disease activity and fibrosis.[4] Liver biopsy may not be required in all patients with chronic hepatitis B, but may be required especially in immune-tolerant and in chronic disease with persistent elevation of ALT, to assess disease activity. Non-invasive tests of liver fibrosis with ultrasound shear wave elastography or magnetic resonance elastography, which can estimate stage of disease, reducing the need for liver biopsy, are increasingly used and included in guidance for viral hepatitis and MASLD.[29][57][70][74][75][76][77]

If Wilson's disease is strongly considered, and all initial investigations are negative, tissue copper measurement by dry weight (e.g., liver biopsy) helps in the diagnosis.[71] A diagnostic algorithm for Wilson disease based on the Leipzig Score for a range of clinical and laboratory findings provides good diagnostic accuracy.[78]

Imaging studies (abdominal ultrasound, CT with contrast, abdominal magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] with contrast).[66] These may help to confirm a diagnosis of MASLD, evaluate for vascular or biliary abnormalities, and assess for features of portal hypertension. Abdominal ultrasound scan findings in many of these conditions are non-specific. It may be performed for surveillance for other conditions such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

International diagnostic criteria for autoimmune hepatitis.[79] The sensitivity of this criteria for definite or probable autoimmune hepatitis is 89.9%. However, this scoring system is cumbersome and not frequently used.

Alcoholic hepatitis risk stratification scales

Scoring scales have been developed to assess the severity of alcoholic hepatitis. These include the Maddrey discriminant function, the Glasgow alcoholic hepatitis score, the Child-Turcotte-Pugh index, and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD).[80][81] A MELD score >20 can be used to stratify disease severity, predict the risk of short-term mortality, and guide the use of corticosteroid therapy.[18]

The Lille score risk-stratifies patients with alcoholic hepatitis who have received up to 7 days of corticosteroid therapy. A score >0.45 at day 7 indicates high risk of mortality.[82] The Lille score at day 4 of corticosteroid therapy has been shown to be as accurate as day 7 Lille score in predicting the outcome and response to treatment.[18][83][84]

Tests: cholestatic/mixed pattern

When there is a cholestatic/mixed pattern abnormality on the liver test, imaging studies of the gallbladder and biliary tree (e.g., abdominal ultrasound scan) are performed.[66] If biliary duct dilation or stricture is considered because of a suggestive history, and liver test results demonstrate a cholestatic pattern or there are suggestive findings on ultrasound imaging, then magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) should be considered.[46] When performed by people experienced in these techniques, ERCP and MRCP are equally sensitive for the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis.[85] With widespread availability of MRCP, use of more invasive ERCP should usually be limited to relieving biliary obstruction (stricture or stones).

Dynamic contrast imaging study (with abdominal CT scan or MRI) should be considered to assess liver nodules. The diagnosis can be confirmed if required by image-guided liver biopsy. ERCP and brushings (if positive on cytology) can confirm a diagnosis of biliary malignancy.[86] A tissue sample for confirmation can also be obtained if required by endoscopic ultrasound scan. Specific conditions may require particular additional tests to confirm the diagnosis, as follows.

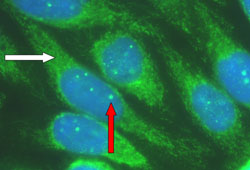

Primary biliary cholangitis (elevated ALP and bilirubin). Anti-mitochondrial antibody is positive in 95% of cases, usually with a high titre (>1:160). Antinuclear antibody and smooth muscle antibody can be positive. Liver biopsy can confirm the diagnosis and determine the degree of fibrosis but is not required to establish diagnosis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic auto-antibody patterns in primary biliary cholangitis. White arrow: anti-mitochondrial staining; red arrow: multiple nuclear dot ANA stainingFrom the collection of David E.J. Jones, BA, BM, BCh, PhD, FRCP, University of Newcastle, UK [Citation ends].

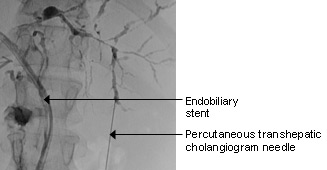

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (elevation of bilirubin exceeds ALP). Perinuclear anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody may be positive; imaging studies with MRCP or ERCP can be diagnostic; liver biopsy also helps stage disease severity.[87][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Typical ERCP findings in a patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis: multi-focal strictures of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ductsFrom the collection of Kris V. Kowdley, MD, University of Washington, WA [Citation ends].

Malignancy: many hepatic malignancies are metastatic from another site. Dynamic contrast imaging studies can be diagnostic‚ or can help in achieving a diagnosis‚ of HCC.[88] One meta-analysis reported that MRI has higher sensitivity than CT for the diagnosis of HCC (82% vs. 66%), with similar specificity (92% vs. 91%).[89] The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases does not recommend MRI and CT for the diagnosis of HCC.[88] The choice of study depends on patient and organisational factors. Significant elevation of alpha-fetoprotein (>400 microgram/L [>400 nanograms/mL]) also suggests HCC. Image-guided liver biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis, but is not essential in patients with cirrhosis at high risk of HCC who meet stringent criteria on dynamic contrast imaging studies.[88] Key features include size ≥1 cm and arterial-phase hyper-enhancement; additional key features depend on the exact lesion size.[88]

Granulomatous and infiltrative diseases, such as Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (laboratory studies are non-specific; ALP and bilirubin may be elevated, with near-normal ALT and AST). Contrast imaging (CT/MRI) is suggestive, but liver biopsy can be diagnostic.

Tests: elevated bilirubin

When bilirubin is elevated and all other liver tests are normal, bilirubin needs to be fractionated to evaluate for the predominant component that is elevated (conjugated versus unconjugated bilirubin).[73] Liver diseases must be considered in cases where the contribution of conjugated bilirubin is significant (>10% of total bilirubin if conjugated portion is elevated), even if the other liver tests are normal.

Gilbert's syndrome

This is not actually a disease, and is the most common cause of mild bilirubin elevation. The other liver tests are normal and ≥90% of bilirubin is unconjugated. A fasting bilirubin test is rarely needed but demonstrates an elevation of bilirubin with 48 hours of fasting, with return to normal within 24 hours of eating a normal diet. A urine test for bilirubinuria is negative. The major differential diagnosis of unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia is haemolysis. Therefore, FBC, reticulocyte count, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), direct antiglobulin test, and blood smear are performed. A genetic test demonstrating homozygosity of TATA gene A(TA7)TAA alleles, instead of A(TA6)TAA, can confirm the diagnosis.[90]

Increased haemolysis

In patients with predominantly unconjugated bilirubinaemia (≥90% unconjugated [indirect]), the most common causes are associated with increased haemolysis. Blood tests should include haemoglobin, RBC count, reticulocyte count, LDH, blood peripheral smear, and direct antiglobulin test. Haemoglobin electrophoresis is also performed in patients with an ethnic background that increases the risk of disorders of haemoglobin (e.g., thalassaemia). These patients may also have increased risk for gallstones, and an imaging study of the abdomen may be required in appropriate clinical settings.

Large biliary duct obstruction

The most common initial imaging study is abdominal ultrasound. Based on the history, physical examination, and subsequent laboratory and ultrasound tests, further imaging studies may be required.[66] A contrast imaging study (CT/MRCP) is usually diagnostic in extrahepatic obstruction. ERCP can be therapeutic.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer