Approach

A careful history, a meticulous physical examination, and a peripheral white blood cell karyotype are crucial in making an accurate diagnosis of Turner syndrome.

History

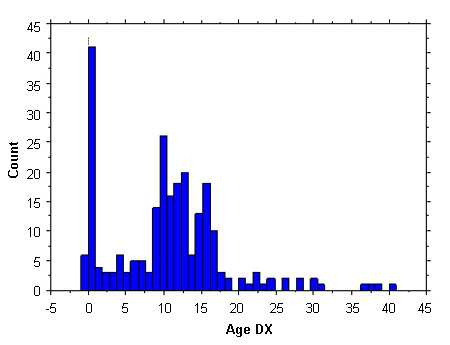

Age at diagnosis

Relatively few patients are diagnosed during early childhood. The largest proportion of detection is aged from 10-16 years, owing to a combination of marked short stature and delayed puberty. Less than 10% of cases are diagnosed antenatally, and a further 20% are detected in infancy, owing to the presence of lymphoedema, neck webbing, and/or congenital heart defects. Another 10% are diagnosed in adulthood, owing to secondary amenorrhoea. The ascertainment profiles in Europe and the US are similar.[9][10]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ascertainment profile data of Turner syndrome; 300 females; Age DX, age (in years) at diagnosisFrom the personal collection of Carolyn Bondy, MS, MD (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development natural history study 2001-2007); McCarthy K, et al. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2008;3:771-775 [Citation ends].

Birth history

Approximately 10% of newborns with Turner syndrome clinically manifest severe congenital heart disease, such as aortic stenosis, aortic coarctation, or left heart hypoplasia. However, many more have defects that are clinically silent or subtle, such as bicuspid aortic valve or partial anomalous pulmonary venous connections.[23] The diagnosis may be obvious at birth, occasionally owing to cardiac features or to lymphoedema (puffy dorsum of the feet) or neck webbing.

Short stature

Poor growth is often the primary symptom. Girls with Turner syndrome are relatively small from infancy and usually fall below the fifth percentile for height on age- and sex-specific growth charts by 10 years of age. Height can also be evaluated using Turner-specific parameters. Magic Foundation: growth charts Opens in new window

The growth history of the child should therefore be taken, focused on potential causes of short stature in childhood. A detailed history of family stature (parents, siblings) should also be obtained. Serial measurements may reveal a downward crossing of percentiles, suggesting an abnormally low growth velocity.

Length should be measured supine in infants until 2 years of age, then measured standing thereafter. Short stature is proportionate, involving both the torso and the lower extremities equally.

A child's growth is related strongly to his or her genetic potential, and the growth deficit has to be assessed using the mid-parental height prediction to identify the girl's genetic growth track. The mid-parental height in a girl is calculated as follows:

(height of mother in centimetres + height of father in centimetres)/2.0 to 6.4 cm [(height of mother in inches + height of father in inches)/2.0 to 2.5 inches].

Delayed puberty

Approximately 15% of girls continue to have functional ovarian tissue and spontaneous puberty, although the majority present with delayed puberty and primary amenorrhoea. Almost all girls experience premature menopause.[7]

Other medical history

Unusually severe or frequent bouts of otitis media in childhood.

Poor social skills.

Physical examination

General examination may reveal pathognomonic dysmorphic features:

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pathognomonic features of Turner syndromeFrom the personal collection of Carolyn Bondy, MS, MD (with data from Ullrich O. Z. Kinderheilk. 1930;49:271-76 and Turner HH. Endocrinology. 1938;23:566-74) [Citation ends].

Other features include:

Down-sloping eyes, ptosis, or hooded eyes

Multiple melanocytic naevi

Dystrophic, hyper-convex nails

Scoliosis.

Pubertal status

Sexual hair is typically sparse and pubertal development minimal.

Cardiovascular examination

Murmur or a click is suggestive of aortic valve disease.

BP should be measured in all extremities, and the femoral pulses should be palpated. Hypertension in one or both upper extremities suggests aortic coarctation.

Prevalence of congenital heart disease is much higher in those with clear evidence of fetal lymphoedema, which can be described as swelling of tissues, especially of the head and neck, due to impaired lymphatic development. The common postnatal manifestations are neck webbing with low-set ears and hairline.

Comorbidities/complications observed frequently with Turner syndrome are shown below.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Association of cardiovascular defects with neck webbingCompiled data from Sachdev V, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1904-1909, and Loscalzo ML, et al. Pediatrics. 2005;115:732-735 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comorbidities and complications in girls with Turner syndrome; diagnosis of congenital heart defects was made by echocardiogram and cardiac magnetic resonance angiography; renal and hepatic imaging was done by ultrasound; hypertension was determined by ambulatory BP monitoring using height-based standards; *includes partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, elongated transverse arch of the aorta, right aortic arch; ** >10% elevation of ALT and/or ASTMcCarthy K, et al. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2008;3:771-775 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comorbidities and complications in girls with Turner syndrome; diagnosis of congenital heart defects was made by echocardiogram and cardiac magnetic resonance angiography; renal and hepatic imaging was done by ultrasound; hypertension was determined by ambulatory BP monitoring using height-based standards; *includes partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, elongated transverse arch of the aorta, right aortic arch; ** >10% elevation of ALT and/or ASTMcCarthy K, et al. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2008;3:771-775 [Citation ends].

Karyotype

The gold standard for diagnosis for the past three decades has been the cytogenetic analysis of a peripheral blood karyotype, and this test underlies most clinical observations and prognostic information. Newer, molecular testing methods using DNA sequencing or microarray analyses have been advanced in recent years but are not yet widely available.[24][25]

A peripheral white blood cell karyotype with 30 cells examined is the standard test for diagnosis.[26] More than 10% of cells miss all or a significant part of a sex chromosome. This test identifies 10% mosaicism or greater with 95% confidence. It is indicated in:[27]

A female with one of the following clinical features:

Fetal cystic hygroma or hydrops, especially when severe

Idiopathic short stature

Characteristic facial features

Obstructive left-sided congenital heart defects

Unexplained delayed puberty or menarche

Couple with unexplained infertility

A female with at least two of the following clinical features:

Renal anomaly (horseshoe, absence, or hypoplasia)

Madelung deformity

Neuropsychological problems or psychiatric issues

Multiple typical or melanocytic nevi

Dysplastic or hyperconvex nails

Other congenital heart defects

Age <40 years with hearing impairment and short stature.

It is recommended that the test should be repeated in the following instances:[5]

Infants diagnosed antenatally should have a postnatal karyotype to confirm the diagnosis

Individuals diagnosed by buccal swab only

Individuals with a karyotype performed in the distant past

When the original report is not available for review.

A 15-mL blood sample, collected using sterile technique and kept at room temperature, is sent to the genetic laboratory within 24 hours. A minimum of 20 cells need to be scored for chromosome number according to the American College of Medical Genetics when looking for possible sex chromosome abnormalities in which mosaicism is common. The analysis is complete if mosaicism is confirmed. If one cell with a sex chromosome loss, gain or re-arrangement is observed within the first 20 cells analysed, a minimum of 10 additional cells should be evaluated.[28][29]

In patients with a strong suspicion of the diagnosis, if the test proves <10% of cells to be abnormal, more metaphases need to be counted along with fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH), or other cell types may be analysed with interphase FISH, in consultation with a geneticist and/or cytogeneticist.[30] Based on the cytogenetics, patients with Turner syndrome can be classified as:

Non-mosaic 45,X

Single X chromosome in all somatic cells (monosomy X); comprises about 60% of patients with Turner syndrome.

Fragmented X or Y

Xp deletions (46,X,delXp), isoXq chromosomes (46,X,iXq), Xq deletions, and ring X or Y chromosomes with substantial interstitial deletions. The isoXq chromosome, consisting of deletion of Xp and fusion of two long arms, is the most common structural anomaly associated with Turner syndrome. Deletion of major portion of Xp is also associated with the syndrome. Often the abnormal sex chromosome is lost in some cells during embryonic development, resulting in a mosaicism of a 45,X cell line in addition to the 46,X, fragX line (see figure A below).

Detection of a small ring or marker chromosome will need further analysis with FISH with Y-specific markers. Those with a clear Y chromosome need further assessment in view of the risk of gonadoblastoma.

Mosaic 45,X

Two types of mosaicism exist.

Loss of a sex chromosome during early embryonic cell divisions may result in a mixture of normal 46,XX cells and 45,X cells in variable proportions throughout body tissues, and includes about 15% of patients with Turner syndrome; for example, 45,X (50%)/46,XX (50%) (see figure B i. below). The relative proportion of normal cells in different tissues will influence the phenotype.

By contrast, formation of a 46,X,abnX embryo is often accompanied by loss of the fragmented X during some embryonic cell divisions, resulting in mosaicism for a monosomic, 45,X cell line along with a cell line containing a fragmented X; for example, iXq (see figure B ii. below). This individual has no normal cells, and the full phenotype is expected.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: X chromosome abnormalities in Turner syndrome; see text for explanationFrom the personal collection of Carolyn Bondy, MS, MD [Citation ends].

Subsequent investigations

Bone age

Radiography is the method of assessing skeletal maturation. Typically, it shows mild delay (2 years less than chronological age). Assessing potential for growth is recommended in all pre-pubertal girls with the syndrome.

Serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH)[5]

Elevated FSH and very low or undetectable AMH predicts complete ovarian failure. However, ovarian potential cannot be predicted with certainty in young girls, as FSH levels elevate into the menopausal range only at the age of normal puberty in those with ovarian failure.

Pelvic ultrasound

Identifies an immature uterus and small streak ovarian morphology.

Performed in older girls and women.

The ovaries form normally in 45,X female fetuses, although most demonstrate accelerated oocyte death and ovarian degeneration into fibrous streaks.[21]

Skeletal survey

Performed in childhood at 5-6 years and 12-14 years to evaluate associated anomalies, such as wrist deformities and scoliosis.[5]

Madelung deformity (prominent distal ulna) is found in only approximately 5% of patients, but lesser degrees of wrist anomalies that can lead to functional problems are common.

Baseline blood tests to screen for comorbidities/complications[5]

Thyroid function tests (TFTs) for autoimmune thyroid disease in all patients at diagnosis. Antithyroid antibodies may be measured if TFTs are abnormal.

LFTs to rule out 'Turner hepatitis' if aged 10 years or older.

Fasting glucose and HbA1c to identify risk of diabetes if aged 10 years or older.

Serum lipids for evidence of dyslipidaemia if aged 18 years or older, and if there is at least one risk factor for cardiovascular disease (check also regional recommendations).

IgA level and tissue transglutaminase IgA to screen for coeliac disease if aged 2 years.

Vitamin D levels checked after the age of 9 years.

Additionally, at the time of diagnosis, the following should be carried out:

Screening for conductive and/or sensorineural hearing loss[5]

A formal audiologic assessment should be performed to assure early and adequate technical and other rehabilitative measures.

Screening for refractive errors and visual abnormalities[5]

Strabismus, amblyopia, hyperopia and myopia, ptosis and colour blindness have all been reported. Females with Turner Syndrome have an epicanthal fold (upper eyelid fold that covers inner corner of eye) and hypertelorism (increased distance between eyes). A comprehensive ophthalmological examination should be performed between aged 12 and 18 months or at the time of diagnosis, if at an older age.

Screening for congenital renal anomalies

A renal ultrasound should be done to assess the presence of structural abnormalities, such as horseshoe kidney, renal agenesis, and duplicated collecting system, which affects approximately 25% of patients with Turner syndrome.[3][4][5] Renal function is usually normal, but obstruction of the collecting system is associated with urinary infection and may need correction.

Screening for congenital cardiovascular defects

At the time of diagnosis no matter what age, a comprehensive cardiovascular evaluation should be done by a consultant in congenital heart disease.[27]

Visualisation of the aortic valve, thoracic aorta and pulmonary veins should be attempted by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) in infants or by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging or CT in older children and adults. CMR requires sedation in young patients and thus, if clinical and echocardiographic evaluations appear normal, it is reasonable to wait until the child is old enough to co-operate without sedation (usually 9-10 years) to perform a screening CMR.

An ECG should be done to assess for potential conduction and repolarisation abnormalities.

If congenital defects are found, follow-up and treatment are dictated by the individual defect.[27] Children with cardiovascular defects should be transitioned to an adult congenital heart disease surgery because they are at continued risk for aortic complications during adult years.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cardiac MRI revealing normal aortic arch in ‘candy cane’ configuration on the left, compared with a previously undiagnosed aortic coarctation, just after the origin of the left subclavian artery (arrow), detected by MRI in an adult woman with Turner syndrome with severe upper body hypertensionFrom the personal collection of Carolyn Bondy, MS, MD (NIH study) [Citation ends].

Aortic coarctation and bicuspid aortic valves are the most common abnormalities. Other abnormalities include partial anomalous pulmonary veins, left heart hypoplasia, and a dilated aorta. Prevalence of cardiovascular defects is much higher in those with clear evidence of fetal lymphoedema, such as neck webbing. A functionally bicuspid valve as a result of complete or partial fusion of the right and left coronary leaflets is seen in 30% of asymptomatic patients, and poses a risk for infection, valve deterioration, and aortic dilation and dissection.[18] Congenital cardiovascular defects constitute the major source of premature mortality in Turner syndrome. Two genes,TIMP1 and TIMP3, which are both located on the short arm of the X chromosome when hemizygous increase the risk of aortopathy with an odds ratio of 12.86.[19] An aortic coarctation, on MR angiography (MRA), will be revealed as a focal narrowing as opposed to a normal aortic appearance of a smooth, 'candy cane'-shaped aortic arch.

Algorithms based on the American Hear Association's guidelines for cardiovascular health in TS will aid in the investigation and follow-up.[27]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Algorithm for screening and monitoring congenital cardiovascular disease in Turner syndrome in girls aged <15 yearsAdapted from: Gravholt CH, Andersen NH, Conway GS, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: proceedings from the 2016 Cincinnati International Turner Syndrome Meeting. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177(3):G1-G70. [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Algorithm for screening and monitoring congenital cardiovascular disease in Turner syndrome in women and girls aged >15 years. (CHD, congenital heart disease; AV, aortic valve; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; PAPV, partial anomalous pulmonary veins; Coarc, coarctation; ACH, adult congenital heart; CVS, cardiovascular system; HTN, hypertension)Adapted from: Gravholt CH, Andersen NH, Conway GS, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: proceedings from the 2016 Cincinnati International Turner Syndrome Meeting. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177(3):G1-G70. [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer