Approach

Initial assessment should include the following:

Vital signs.

Patient history.

Physical examination, with attention to signs and symptoms of hypoxaemia, dehydration, sepsis, or shock.

In patients with suspected infection or other complications: full blood count (FBC) and basic metabolic panel (BMP). Prothrombin time (PT)/international normalised ratio (INR) and/or activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT) should be checked in patients on anticoagulation or with suspected coagulopathy.

In patients where chest discomfort/pain is a complaint, cardiac enzymes and a baseline ECG should be obtained to rule out a cardiac aetiology of symptoms.

Conventional radiography of the chest/abdomen.

Risk assessment. The patient's age, clinical condition, and comorbidities, as well as foreign body size, composition, and anatomical localisation of the object, may help to differentiate low-risk from high-risk patients and determine if an endoscopic procedure needs to be performed as an emergency (within 2-6 hours)[34] or urgently (within 24 hours of admission).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Diagnostic and treatment algorithm for foreign body ingestionFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz [Citation ends].

Urgent diagnostic considerations

The initial diagnostic evaluation involves an assessment of haemodynamic stability and resuscitative treatment if necessary. ABC (airway, breathing, circulation) should be implemented, with resuscitative measures administered as required.

Cultures should be obtained in patients with signs or symptoms of septicaemia or elevated white blood cell count at presentation.

History and clinical presentation

Once the patient is stabilised, a complete history should be obtained in order to determine the object ingested, severity of symptoms, history of similar events in the past, medications, concurrent medical problems, and previous surgical interventions. The clinical presentation will vary depending on where the object is localised.

Oropharyngeal foreign bodies

Diagnosis and management in most children is challenging because of the intrinsic complexity of communication and physical examination. Young children often put any object they find into their mouth and may accidentally swallow them. Parents usually bring their children to the accident and emergency department or primary doctor's clinic with no clear history of foreign body ingestion. They may present with respiratory symptoms such as stridor, wheezing, and pneumonia that may indicate an impacted foreign body in the hypopharynx, oesophagus, or respiratory tree.[1][2] Adults normally present at the accident and emergency department or primary doctor's clinic with a foreign body sensation that something has become trapped in their throat, resulting in dysphagia or pain on swallowing, especially after eating. They are usually able to point towards the area of sensation at this level (well-innervated area). The level of discomfort may vary. The signs of occlusion may vary from minor to more severe, such as drooling, and inability to swallow solids and liquids. On rare occasions, patients may have airway compromise (stridor and wheezing) if large objects are trapped in this area of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Most oropharynx foreign bodies can be detected using selective soft tissue neck x-ray, chest x-ray, tongue depressor, and transnasal laryngoscopy.[13]

Choking while consuming food, the 'cafe coronary syndrome', is a type of upper airway obstruction caused by a food bolus at the level of the hypopharynx and can lead to death. This is more likely to occur in individuals who eat too fast or chew their food improperly, those with dentures, psychiatric patients, individuals who use drugs or consume alcohol, and those who are laughing or talking simultaneously while eating.[31]

Oesophageal foreign bodies

The classic presentation of an adult patient with an oesophageal foreign body is a patient with a prior history of minor recurrent swallowing problems (potentially due to an underlying mechanical, inflammatory, or functional obstruction), or a lack of teeth or unfitted dentures, who presents with a sensation that something became trapped after a meal (patients usually point towards the lower chest or upper abdominal area: the 'steak-house syndrome'), with or without the ability to handle secretions (partial or complete obstruction). The most common cause of upper GI foreign bodies in adults involves a bolus of food (common causes include pork or chicken meat) that does not pass through the oesophagus because of underlying anatomical, inflammatory, or functional oesophageal pathology. Patients with oesophageal foreign body obstruction should be asked about alcohol intake, use of sedatives or hypnotic agents, dentures, underlying oesophageal disease, previous endoscopies or surgeries (e.g., Nissen's fundoplication), and circumstances surrounding the ingestion. Signs or symptoms that suggest potential perforation include fever, tachycardia, peritonitis, subcutaneous crepitus, and swelling of the neck, chest, or abdomen.

In children with an ingested foreign body, the classic symptoms include gagging, vomiting, and pain in the neck and/or throat. The presentation can be less specific and may include irritability, poor feeding, failure to thrive, fever of unknown origin, non-specific pulmonary symptoms, recurrent pneumonia, or asthma attack. Diagnosis in these cases requires a high index of suspicion. Up to one third of the children with an oesophageal foreign body are asymptomatic and the foreign body could be an incidental finding.

Stomach/small intestine foreign bodies

Patients may present with a history of swallowing an object or a history of recent placement of an oesophageal or gastric prosthesis such as a self-expandable plastic stent (SEPS) or a fully covered self-expandable metal stent (SEMS). They may present with vague symptoms such as fever, abdominal pain, early satiety, nausea, and vomiting or be completely asymptomatic (foreign body found incidentally during radiological evaluation). People with psychiatric pathologies or who have an intellectual disability may swallow a wide variety of objects, including multiple, large, or unusual items. Prisoners may swallow objects either to hide them from the authorities or to seek medical care. People who smuggle drugs may swallow multiple condoms (usually double wrapped) filled with cocaine or heroin. They may present with acute abdominal pain or, if the condoms rupture, with an acute intoxication.

Large intestine/rectum foreign bodies

Large bowel impacted objects may result from migration down from the upper GI tract. However, this is rare and typically requires the presence of a stricture in the colon or rectum. More commonly, large bowel impacted objects result from the insertion of an object via the rectum. In rare situations, the object may cause a penetrating injury.[35][36][37][38]

A colorectal foreign body that causes a perforation in an extraperitoneal segment of the colon or rectum may not initially present with severe physical findings. A strong index of suspicion should be maintained for perforation of the extraperitoneal colon (e.g., lower rectum below the peritoneal fold), especially if the patient has a delay in presentation to medical care.

Physical examination

Delayed presentations are most common in children and people who have an intellectual disability. Whenever there is a history of foreign body ingestion, a complete physical examination - including visualisation of the nares, ear canals, and oropharynx - should be performed. Signs of upper GI obstruction can be non-specific, and can include intercostal musculature retraction, tachypnoea, stridor, wheezing, cyanosis, abdominal tenderness, salivation/drooling, and inability to swallow. Patients with rectal foreign bodies may or may not present with haematochezia.

It is also important to keep in mind that patients can ingest more than one object, and the search for foreign bodies should not be suspended just because one object has been found. Children, people who have an intellectual disability, prisoners, and patients with psychiatric pathologies are especially prone to ingesting multiple foreign bodies. Occasionally, a foreign body in the oropharynx can be visualised during the physical examination and can be removed at the time. The oral cavity and oropharynx can be examined with the help of a tongue depressor.[13]

Initial investigations

Most patients with GI foreign bodies do not require any laboratory tests. However, in patients with signs and symptoms consistent with infection or other complications, the following tests are recommended: FBC and BMP.

Blood type and antibody testing should be obtained if blood transfusions are needed. PT/INR and/or activated PTT should be checked in patients on anticoagulation or with suspected coagulopathy.

ECG and cardiac enzymes (e.g., troponin) should be checked in patients with co-existing chest pain.

Imaging

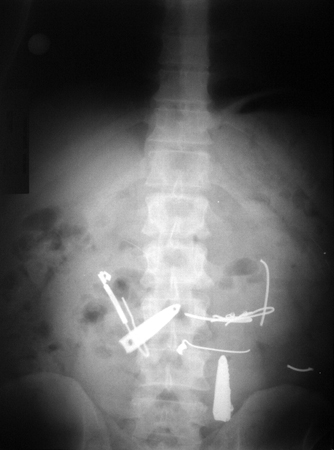

Plain film imaging (x-ray) [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plain abdominal radiology showing foreign body in the stomach lumenFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plain abdominal x-ray showing multiple foreign bodies. There were no signs of intestinal obstruction or perforationFrom: Canda AE. BMJ Case Reports. 2009;2009:bcr12.2008.1354 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plain abdominal x-ray showing multiple foreign bodies. There were no signs of intestinal obstruction or perforationFrom: Canda AE. BMJ Case Reports. 2009;2009:bcr12.2008.1354 [Citation ends].

In children, people who have an intellectual disability, and patients with psychiatric pathologies, a mouth-to-anus radiograph should be obtained (x-ray of the neck, chest, and abdomen/pelvis).

In those with suspected upper GI foreign body, a neck x-ray, selective lateral soft tissue neck x-ray, chest x-ray (including a posteroanterior and lateral view), and abdominal x-ray should be part of the initial diagnostic evaluation.

In those patients with a suspected rectocolonic foreign body, a plain film abdominal x-ray (including a flat and upright film) should be obtained to identify objects and rule out pneumoperitoneum.

Flat objects such as coins are usually seen in a coronal alignment on anteroposterior or frontal x-rays.[39] If the foreign body is in the trachea, it presents in a sagittal orientation because the tracheal rings are incomplete in the posterior wall.

Food impaction is not seen in plain radiography; however, embedded bony fragments can sometimes be seen. Radiography does not always reliably detect radiolucent foreign bodies, especially fish bones. Even when bones are sufficiently radiopaque to be visualised on radiography, the large body habitus in an obese patient can sometimes make it difficult to detect them.

Metallic objects (except aluminium), most animal bones (except some fish bones, such as those of trout, mackerel, and herring), and glass materials are opaque on x-rays. Most plastic and wooden materials are not opaque on x-ray.[40]

Retained objects in the rectum can also ascend higher into the colon (hepatic flexure). Occasionally, the object can perforate the colon and lodge in the retroperitoneum or may lie free within the peritoneum, induce a contained abscess, or travel to a distant part of the body.[41][42]

Computed tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is indicated when x-rays and/or endoscopy fail to localise a foreign body. This includes situations where there is suspicion for a non-metallic foreign body (e.g., plastic or wooden object, or fish bone) or perforation. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy clinical guideline recommends a CT scan in all patients with a suspected perforation or other complication that may require surgery.[34] Some paediatric guidelines suggest considering CT for radiolucent foreign bodies.[43]

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging may reveal non-metallic foreign bodies but is contra-indicated if ingestion of a magnet or other metal is suspected.

Oesophagram with barium or gastrografin

The general consensus is that oesophagography with barium or gastrografin does not add to the evaluation for ingested foreign bodies and delays definitive treatment. Moreover, there is a risk of pulmonary complications if the contrast medium is aspirated and the contrast can limit endoscopic visualisation. Barium is contraindicated in cases in which oesophageal perforation is suspected; however, gastrografin may be used if a study is needed to localise the level of perforation.

Endoscopy

Endoscopy is generally the first-line modality for the extraction of foreign bodies within the GI tract (from oesophagus to anus).[44][45][46] The hypopharynx and posterior third of the tongue can be assessed by indirect transnasal laryngoscopy.[13]

However, endoscopic evaluation is contraindicated in certain circumstances. Absolute contraindications include severe hypotension/shock, acute perforation, acute myocardial infarction, peritonitis, and ingestion of drug (cocaine) packets (due to the increased risk of rupture during attempted endoscopic removal). Relative contraindications include poor patient cooperation and cardiac arrhythmias or recent myocardial ischaemia.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic photograph of a food impaction in the lower oesophagus with evident concentric mucosal ring suggesting eosinophilic oesophagitisFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Impacted food bolus removed from lower oesophagusFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Impacted food bolus removed from lower oesophagusFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscope view showing foreign bodies in the stomach lumenFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscope view showing foreign bodies in the stomach lumenFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Foreign bodies removed from the stomachFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Foreign bodies removed from the stomachFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: (A) Endoscopic view of impacted nail-clipper in the duodenum. (B) Endoscopic removal of tie-clipFrom: Canda AE. BMJ Case Reports. 2009;2009:bcr12.2008.1354 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: (A) Endoscopic view of impacted nail-clipper in the duodenum. (B) Endoscopic removal of tie-clipFrom: Canda AE. BMJ Case Reports. 2009;2009:bcr12.2008.1354 [Citation ends].

Other devices

A hand-held metal detector is an accurate, radiation-free, cost-effective, non-invasive screening tool that is useful in identifying and localising metal items such as coins ingested by children.[47][48][49][50][51]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer