Treatment algorithm

Please note that formulations/routes and doses may differ between drug names and brands, drug formularies, or locations. Treatment recommendations are specific to patient groups: see disclaimer

Look out for this icon: for treatment options that are affected, or added, as a result of your patient's comorbidities.

postoperative ileus

1st line – nothing by mouth (NPO) and intravenous hydration

nothing by mouth (NPO) and intravenous hydration

All patients with ileus should be made NPO and will require intravenous hydration.

The initial choice of intravenous solution will depend on the baseline hydration state of the patient and comorbidities.

A significantly hypovolemic patient may benefit from a bolus of several liters of normal saline.

Following this initial hydration, the maintenance intravenous solution should be physiologic and provide some glucose.

This rate should be tailored to the patient's urine output and hemodynamics.

Electrolytes should be monitored and replaced as necessary during this period.

Plus – reduction in opioid analgesia ± replacement with nonopioid analgesia

reduction in opioid analgesia ± replacement with nonopioid analgesia

Treatment recommended for ALL patients in selected patient group

Opioid analgesics have been shown to slow down bowel motility.[3]Wattchow D, Heitmann P, Smolilo D, et al. Postoperative ileus- an ongoing conundrum. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 May;33(5):e14046. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33252179?tool=bestpractice.com

Decreasing the use of systemically administered opioid analgesics has shown to help prevent the development of postoperative ileus.[28]Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(®)) Society recommendations: 2018. World J Surg. 2019 Mar;43(3):659-95. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00268-018-4844-y http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30426190?tool=bestpractice.com Patient-controlled opioid analgesia reduces the overall amount of opioid given compared with round-the-clock analgesic dosing administered by a nurse.[33]Chan KC, Cheng YJ, Huang GT, et al. The effect of IVPCA morphine on post-hysterectomy bowel function. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 2002 Jun;40(2):61-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12194392?tool=bestpractice.com

Useful adjuncts for pain management include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ketorolac, and other nonopioid analgesics such as acetaminophen.[38]Schlachta CM, Burpee SE, Fernandez C, et al. Optimizing recovery after laparoscopic colon surgery (ORAL-CS): effect of intravenous ketorolac on length of hospital stay. Surg Endosc. 2007 Dec;21(12):2212-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17440782?tool=bestpractice.com [39]Chen JY, Wu GJ, Mok MS, et al. Effect of adding ketorolac to intravenous morphine patient-controlled analgesia on bowel function in colorectal surgery patients: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005 Apr;49(4):546-51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15777304?tool=bestpractice.com [40]McNicol ED, Ferguson MC, Schumann R. Single-dose intravenous ketorolac for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 May 17;5(5):CD013263. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD013263.pub2/full http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33998669?tool=bestpractice.com [41]Bell S, Rennie T, Marwick CA, et al. Effects of peri-operative nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on post-operative kidney function for adults with normal kidney function. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Nov 29;11(11):CD011274. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011274.pub2/full http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30488949?tool=bestpractice.com [42]Chen JY, Ko TL, Wen YR, et al. Opioid-sparing effects of ketorolac and its correlation with the recovery of postoperative bowel function in colorectal surgery patients: a prospective randomized double-blinded study. Clin J Pain. 2009 Jul-Aug;25(6):485-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19542795?tool=bestpractice.com [85]Blank JJ, Berger NG, Dux JP, et al. The impact of intravenous acetaminophen on pain after abdominal surgery: a meta-analysis. J Surg Res. 2018 Jul;227:234-45. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29804858?tool=bestpractice.com [86]Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists' Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016 Feb;17(2):131-57. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26827847?tool=bestpractice.com

Local anesthetic administered via the epidural route is another alternative to opioid analgesia.[3]Wattchow D, Heitmann P, Smolilo D, et al. Postoperative ileus- an ongoing conundrum. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 May;33(5):e14046. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33252179?tool=bestpractice.com [34]Senagore AJ, Delaney CP, Mekhail N, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing epidural anaesthesia and patient-controlled analgesia after laparoscopic segmental colectomy. Br J Surg. 2003 Oct;90(10):1195-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14515286?tool=bestpractice.com [35]Marret E, Remy C, Bonnet F. Meta-analysis of epidural analgesia versus parenteral opioid analgesia after colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2007 Jun;94(6):665-73. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bjs.5825 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17514701?tool=bestpractice.com [36]Gendall KA, Kennedy RR, Watson AJ, et al. The effect of epidural analgesia on postoperative outcome after colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2007 Sep;9(7):584-98;discussion 598-600. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17506795?tool=bestpractice.com [37]Carli F, Trudel JL, Belliveau P. The effect of intraoperative thoracic epidural anesthesia and postoperative analgesia on bowel function after colorectal surgery: a prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001 Aug;44(8):1083-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11535845?tool=bestpractice.com [53]Guay J, Nishimori M, Kopp SL. Epidural local anesthetics versus opioid-based analgesic regimens for postoperative gastrointestinal paralysis, vomiting, and pain after abdominal surgery: a Cochrane review. Anesth Analg. 2016 Dec;123(6):1591-602. https://journals.lww.com/anesthesia-analgesia/fulltext/2016/12000/epidural_local_anesthetics_versus_opioid_based.33.aspx http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27870743?tool=bestpractice.com

For more information on perioperative measures to prevent postoperative ileus, see Prevention.

Primary options

acetaminophen: <50 kg body weight: 15 mg/kg intravenously every 6 hours when required, or 12.5 mg/kg intravenously every 4 hours when required, maximum 75 mg/kg/day; ≥50 kg body weight: 1000 mg intravenously every 6 hours when required, or 650 mg intravenously every 4 hours when required, maximum 4000 mg/day

OR

ketorolac: adults <65 years of age and/or ≥50 kg: 30 mg intramuscularly/intravenously every 6 hours when required, maximum 120 mg/day; adults ≥65 years of age and/or <50 kg: 15 mg intramuscularly/intravenously every 6 hours when required, maximum 60 mg/day

These drug options and doses relate to a patient with no comorbidities.

Primary options

acetaminophen: <50 kg body weight: 15 mg/kg intravenously every 6 hours when required, or 12.5 mg/kg intravenously every 4 hours when required, maximum 75 mg/kg/day; ≥50 kg body weight: 1000 mg intravenously every 6 hours when required, or 650 mg intravenously every 4 hours when required, maximum 4000 mg/day

OR

ketorolac: adults <65 years of age and/or ≥50 kg: 30 mg intramuscularly/intravenously every 6 hours when required, maximum 120 mg/day; adults ≥65 years of age and/or <50 kg: 15 mg intramuscularly/intravenously every 6 hours when required, maximum 60 mg/day

Drug choice, dose and interactions may be affected by the patient's comorbidities. Check your local drug formulary.

Show drug information for a patient with no comorbidities

Primary options

acetaminophen

OR

ketorolac

nasogastric (NG) decompression

Treatment recommended for ALL patients in selected patient group

The NG tube should be placed so the tip is in the stomach, secured, and connected to suction.

Gastric output should be measured and lost volume should be replaced with an intravenous physiologic saline solution.

The decision to remove the NG tube is based on measured gastric output over time and clinical resolution of ileus. The patient is assessed for absence of abdominal distention and cramping, decreasing NG tube output, and passage of flatus and stool with a view to removal of the NG tube. The NG tube may require reinsertion if the patient again displays evidence of ongoing ileus with abdominal distention and vomiting.

Studies have shown that routine NG decompression is unnecessary and may be detrimental. Therefore, NG decompression is reserved for selective use.[87]Nelson R, Edwards S, Tse B. Prophylactic nasogastric decompression after abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD004929. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004929.pub3/full http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17636780?tool=bestpractice.com

Often, orogastric decompression is performed intra-operatively, but the tube is removed at the completion of surgery.[28]Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(®)) Society recommendations: 2018. World J Surg. 2019 Mar;43(3):659-95. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00268-018-4844-y http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30426190?tool=bestpractice.com

nonsurgical cause

NPO and intravenous hydration

All patients with ileus should be made NPO and will require intravenous hydration.

The initial choice of intravenous solution will depend on the baseline hydration state of the patient and comorbidities.

A significantly hypovolemic patient may benefit from a bolus of several liters of normal saline.

Following this initial hydration, the maintenance intravenous solution should be physiologic and provide some glucose.

Fluids should be administered at a maintenance rate according to body weight. This rate should be tailored to the patient's urine output and hemodynamics.

In patients receiving pharmacologic treatment that may exacerbate ileus (e.g., opiates, anticholinergics), discontinuing or reducing such medications aids resolution of ileus.

Electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia, hypochloremia, alkalosis, and hypermagnesemia) may be a consequence of ileus or an exacerbating factor. Electrolytes should be monitored and replaced as necessary during this period.

management of the underlying condition(s)

Treatment recommended for ALL patients in selected patient group

Underlying conditions such as sepsis, intra-abdominal infections, or other systemic illnesses should be treated.

Systemic diseases associated with intestinal hypomotility include diabetes mellitus, Chagas disease, scleroderma, and neurologic diseases.

Chronic opioid use contributes to ileus, but cessation or reduction of opioids should be managed carefully in these patients due to the risk of withdrawal symptoms.[89]Cunningham C, Edlund MJ, Fishman M, et al. The ASAM national practice guideline for the treatment of opioid use Disorder: 2020 focused update. J Addict Med. 2020 Mar/Apr;14(2s suppl 1):1-91. https://journals.lww.com/journaladdictionmedicine/fulltext/2020/04001/the_asam_national_practice_guideline_for_the.1.aspx http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32511106?tool=bestpractice.com [90]Müller-Lissner S, Bassotti G, Coffin B, et al. Opioid-induced constipation and bowel dysfunction: a clinical Guideline. Pain Med. 2017 Oct 1;18(10):1837-63. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5914368 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28034973?tool=bestpractice.com

NG decompression

Treatment recommended for SOME patients in selected patient group

The NG tube should be placed so the tip is in the stomach, is secured, and is connected to suction.

Gastric output should be measured and lost volume should be replaced with an intravenous physiologic saline solution.

The decision to remove the NG tube is based on measured gastric output over time and clinical resolution of ileus. The patient is assessed for absence of abdominal distention and cramping, decreasing NG tube output, and passage of flatus and stool with a view to removal of the NG tube. The NG tube may require reinsertion if the patient again displays evidence of ongoing ileus with abdominal distention and vomiting.

Studies have shown that routine NG decompression is unnecessary and may be detrimental. Therefore, NG decompression is reserved for selective use.[87]Nelson R, Edwards S, Tse B. Prophylactic nasogastric decompression after abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD004929. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004929.pub3/full http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17636780?tool=bestpractice.com

ileus lasting longer than 3 days or prolonging the postoperative recovery

parenteral nutrition

These patients may be kept NPO for several weeks.

Parenteral nutrition is recommended for patients who do not have any oral intake for more than 7 days.[3]Wattchow D, Heitmann P, Smolilo D, et al. Postoperative ileus- an ongoing conundrum. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 May;33(5):e14046. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33252179?tool=bestpractice.com [78]Gero D, Gié O, Hübner M, et al. Postoperative ileus: in search of an international consensus on definition, diagnosis, and treatment. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2017 Feb;402(1):149-58. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27488952?tool=bestpractice.com It is beneficial in patients who are on bowel rest for more than 14 days or who have underlying malnutrition.[88]Sandstrom R, Drott C, Hyltander A, et al. The effect of postoperative intravenous feeding (TPN) on outcome following major surgery evaluated in a randomized study. Ann Surg. 1993 Feb;217(2):185-95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1242758 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8439216?tool=bestpractice.com Electrolytes should be checked daily to identify electrolyte abnormalities associated with postoperative intravenous feeding and the NPO state.

The benefits of starting parenteral nutrition earlier than 7 days are less than the risks associated with parenteral nutrition and central venous access.

In most patients the postoperative "starvation" state is not associated with increased morbidity or mortality.

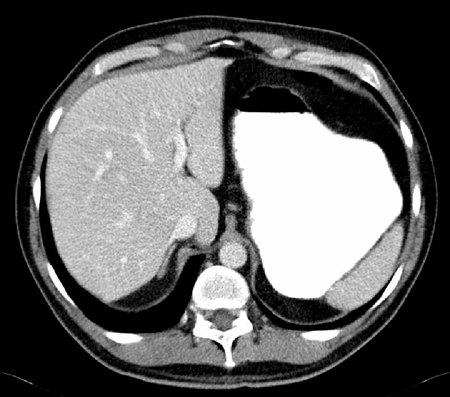

Insertion of a central venous line is associated with increased risk of iatrogenic injury to nearby vessels, pneumothorax, deep vein thrombosis, and central line-associated bacteremia. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing significantly dilated stomachFrom the personal collection of Dr Paula I. Denoya [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nasogastric tubeFrom the personal collection of Dr Paula I. Denoya [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nasogastric tubeFrom the personal collection of Dr Paula I. Denoya [Citation ends].

Choose a patient group to see our recommendations

Please note that formulations/routes and doses may differ between drug names and brands, drug formularies, or locations. Treatment recommendations are specific to patient groups. See disclaimer

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer