Approach

Both conditions may present for the first time to emergency and acute medical settings, as well as to primary care. It is important to establish rapport with patients by showing genuine interest and concern; thorough physical and neurologic exam is vital. Assess for associated comorbid psychiatric conditions, as treatment of such comorbidities benefits overall functioning and recovery. Consider the complete differential diagnosis, including biologic, psychological, and social explanations. Include functional neurologic or somatic symptom disorders in the differential diagnosis before proceeding with the workup, rather than after medical exam to rule out other medical problems.[64]

Use medical tests judiciously, but at initial presentation, patients should have laboratory testing to rule out a reasonably broad differential diagnosis. Explain that normal test results do not mean that nothing is wrong, but that specific other worrisome illnesses in the differential diagnosis have been excluded, or that sometimes abnormalities may be found that are clinically insignificant. Neuropsychological evaluation typically includes both cognitive and personality testing, but it is not necessary for all patients.

History

Being attentive to how patients report their histories will help guide diagnosis and point to common risk factors of alexithymia (difficulty identifying and describing feelings) and neuroticism (lifelong tendencies to experience negative affect and distress).[60][61][62] Emotional processing problems are typical in both disorders, either due to an inability to be aware of emotions or a tendency to suppress and avoid emotions, or due to high neuroticism and emotional reactivity.

The clinician should consider whether patients describe specific symptoms in detail, or whether they focus on how their symptoms have affected their quality of life.

Presentation of somatizing patients may appear vague, dramatic, or odd.[63]

Functional neurologic disorder

Risk factors for functional neurologic disorder are heterogenous and nonspecific, and the underlying cause is still not fully understood. Although recent and remote psychological stressors can be important risk factors and may perpetuate symptoms, patients may present without identifiable stressors.[30] In some patients, symptoms are triggered by physical injury, surgery, or another neurologic disorder such as migraine.[31]

Use the biopsychosocial model as a framework for identifying predisposing vulnerabilities, acute precipitants, and perpetuating factors; pay particular attention to factors with prognostic and treatment implications, such as:[3]

Comorbid pain and fatigue

Psychiatric comorbidities

Active psychosocial stressors

Unhelpful behavioral responses

Unhelpful illness beliefs.

Acutely stressful life events that may precede onset include family/relationship problems and health problems.[32][65] More remote adverse life events (often in childhood) include physical and sexual abuse, as well as emotional neglect.[30] Although asking about adverse life events may help with treatment planning, be sensitive to the fact that it may cause distress and can be perceived as intrusive and inappropriate, especially if there is a history of previous interactions with healthcare professions that explored this and which were viewed negatively by the patient. Follow the patient's cues, and proceed sensitively; consider whether it may be better for this discussion to wait until a follow-up visit.[66]

Somatic symptom disorder

Somatic symptom disorder may begin without any single precipitant, and patients exhibit multiple illness behaviors. This includes behavior in response to feeling ill that is intended to relieve the illness symptoms and results in focusing attention on the illness: for example, going to the doctor or emergency department, avoiding perceived environmental triggers for the illness, and adjusting lifestyle to anticipate the illness. There is excessive time and energy devoted to somatic symptoms or health concerns. Although any one somatic symptom may not be continuously present, the state of being symptomatic is persistent (typically >6 months). A subset of somatic symptom disorder patients have predominantly pain symptoms (previously designated as pain disorder).

Other clues to the diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder on history-taking include:[2]

History of illness may be vague and/or inconsistent

Worries are not alleviated in spite of high utilization of medical care/reassuring investigation results

Patient describes frequently checking their own body

Patient attributes normal sensations to medical illness.

Many patients with somatic symptom or functional neurologic disorder also have cognitive complaints: for example, forgetting whole conversations, unintentionally using the wrong words, forgetting how to do basic activities or tasks that they should know, being unable to multitask, and having short-term memory problems. Patients with functional cognitive disorder may be misdiagnosed as having the early stages of a neurodegenerative disorder.[67][68][69]

Evaluating for comorbidities (in conjunction with relevant diagnostic criteria) is also necessary.[2] Typical comorbid diagnoses include mood disorders, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, dissociative disorders, social or specific phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and personality disorders.[4][5][6] Affective and anxiety disorders can present with somatic symptoms. Near relatives with psychiatric illness or severe somatic disease are also common.[4]

Throughout the history, it is important for physicians to acknowledge the reality of the patient's symptoms, and if relevant explain that presence of a psychiatric or neuropsychiatric disorder would not negate the reality of their physical and emotional suffering.[70]

Examination

In the first instance, carry out a full neurologic exam for patients with suspected functional neurologic disorder, and a full medical/neurologic/psychiatric exam for patients with suspected somatic symptom disorder. Expert consensus is that the formal diagnostic assessment for functional neurologic disorder should include a neurologist/neuropsychiatrist and/or another physician with neurologic exam expertise; therefore, specialist referral is typically required following an initial assessment in primary care.[3][71]

Functional neurologic disorder

Functional neurologic disorder is diagnosed based on positive clinical features that demonstrate impaired voluntary movement or sensation in the presence of intact automatic movement or sensation. In some cases, there is incongruency with pathophysiologic disease.[66] In general, functional movement disorders reveal variability in amplitude and frequency of movements, inconsistent movements, variable direction and pattern to the movements, suggestibility, distractibility, suppressibility, and active resistance to passive movement.[72]

Diagnosis of functional neurologic disorder is often based on one or more (often a combination) of positive physical clinical features, such as:[66]

Functional limb weakness

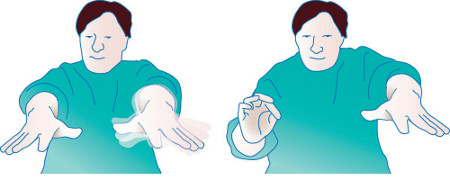

Hoover sign; weakness of hip extension returns temporarily to normal during contralateral hip flexion against resistance.

Hip abductor sign; weakness of unilateral hip abduction returns to normal with attempt at bilateral hip abduction.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: a) Hoover sign; hip extension is weak on direct testing (left) but strength becomes normal when there is contralateral hip flexion against resistance; b) Hip abductor sign; hip abduction is weak on direct testing (left) but strength becomes normal when there is contralateral hip abduction against resistance (right)Stone et al. BMJ. 2020 Oct 21;371:m3745; used with permission [Citation ends].

Functional tremor

Look for evidence of distractibility and/or entrainment with the "entrainment test." Ask the patient to copy rhythmic movements of varying speed made by the examiner between the thumb and forefinger using one hand, and then watch the response in the other hand. Suspect a functional tremor If the tremor in the other hand stops during the test, or if the tremor "entrains" to the same rhythmic pattern, or if the patient is unable to copy the movement.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Entrainment test": watch the other (patient's left) hand while the patient copies the examiner’s rhythmic pincer movements with their right hand; the functional tremor in the left hand stops during the taskStone et al. BMJ. 2020 Oct 21;371:m3745; used with permission [Citation ends].

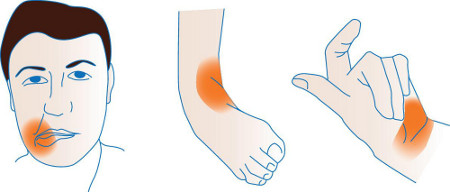

Functional dystonia

Usually presents as a fixed position, usually a clenched fist or inverted ankle (in contrast to other types of dystonia, which are usually mobile).

Functional facial dystonia usually presents with episodic contraction of the platysma or orbicularis.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Functional dystonia; orange shading shows typical areas of fixed muscular contraction in functional dystoniaStone et al. BMJ. 2020 Oct 21;371:m3745; used with permission [Citation ends].

Functional visual loss

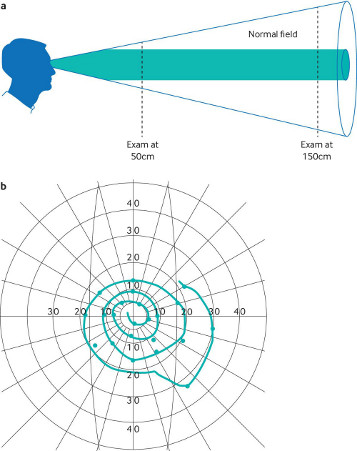

Suggestive features include tubular (as opposed to conical) vision; this means that the visual field at 150 cm distance is the same width as at 50 cm (whereas it would be expected to increase conically with distance).

Patients may also have "spiraling" on Goldmann perimetry, meaning that the longer the test goes on, the more constricted their visual field becomes.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: a) A tubular visual field defect at 150cm which is the same width as at 50cm; b) "Spiralling" on Goldmann perimetryStone et al. BMJ. 2020 Oct 21;371:m3745; used with permission [Citation ends].

Functional seizures[73][74][75][76]

Suggestive features include:

Typically spells have prolonged duration (>5 minutes)

Eyes may be tightly closed

Tearfulness

Hyperventilation during a seizure

Side-to-side head shaking

Can be asynchronous with stop/start quality

May involve back arching, pelvic thrusting, stuttering, flailing motor movements, and speaking in a whisper or baby voice

There may be an emotional or pain trigger.

A smartphone video taken by a friend or family member may help in diagnosis. Continuous video-electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring can be useful in establishing a diagnosis of functional seizures when typical spells are captured.

Other general clues to a functional neurologic etiology across a variety of different symptoms include:[2][66]

Distribution of motor or sensory deficits that does not conform to any nerve, root, truncal, or central distribution (e.g., sharp demarcation at the shoulder or groin, "splitting the midline")

Give-way weakness (when testing motor strength there is sudden collapse after several seconds of full resistance)

Inconsistent examination findings (e.g., severe leg weakness on strength testing in patients who are ambulatory, or patients who describe symptoms of visual impairment but who can avoid obstacles when walking)

Paradoxical sensory findings (midline sensory split and lateralization of the tuning fork)

Pseudoclonus

Convergence spasm

Distractible symptoms

Generalized seizure-like motor movements without loss of awareness

Astasia-abasia (paradoxical ability to use the legs normally except when standing or walking)

Cognitive complaints that are out of proportion for the possible neurologic or medical explanation of symptoms

Dissociative symptoms, such as depersonalization, derealization, and dissociative amnesia, especially at symptom onset or during attacks.

Functional neurologic disorder and neurologic disorders frequently coexist; examples include Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, and epilepsy.[8][9][10] Patients diagnosed with functional neurologic disorder can also later develop neurologic disorders. Therefore, if new symptoms arise, repeated neurologic exams are necessary. Likewise, in somatic symptom disorder, brief, regularly scheduled visits with the same primary physician are preferred to unnecessary workups and interventions.

Somatic symptom disorder

The aims of the physical exam are to assess for any general medical illness, and to monitor any changes over time. It may also provide the patient with reassurance that their concerns are being taken seriously.

Laboratory tests

When patients initially present with new physical symptoms, laboratory testing may be indicated to rule out potential medical or neurologic conditions. If the laboratory tests have already been done and there is no change in the symptoms it is usually not necessary to repeat them.

In established functional neurologic disorder or somatic symptom disorder, it is not necessary to repeat and exhaust all medical evaluations when there is clear evidence of functional neurologic or functional somatic symptoms (and no other indication of neurologic conditions) on neurologic exam. However, as neurologic disorders can coexist or develop later, when new symptoms arise, repeat laboratory evaluations may be necessary.[74] In somatic symptom disorder, unnecessary workups and interventions should also be avoided.

Screening instruments

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD)-7, and the PHQ-15 are brief, well-validated measures for detecting and monitoring depression, anxiety, and somatization.[77]

There are also multiple focused symptom inventories designed to objectively capture specific psychological symptoms or constructs. These include the Beck Depression Inventory-2 (BDI-2), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS).[78][79][80] These are brief self-report questionnaires designed to capture details of experiences of single psychological constructs, such as depression, anxiety, or alexithymia. The Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale (LEAS) is designed to measure a person's ability and capacity for emotional awareness.[81]

Psychological and personality testing

If physicians are interested in obtaining personality profiles for their patients, or if the need to refer for psychiatric evaluation is uncertain, psychological testing can be requested. This can reveal psychopathology or psychological traits that may be contributing to symptoms or that would be helpful to address in treatment. It can support the diagnosis of a somatic symptom or related disorder, although diagnosis cannot be made purely on the basis of psychological testing. Consultation with a psychologist or neuropsychologist is necessary for psychological and personality testing. Although these tests cannot confirm the diagnosis, they can be helpful in formulating positive hypotheses about the potential psychological or personality contributors to the development of somatic symptom or functional neurologic disorder. Standardized psychological testing provides descriptive information about specific personality features that may be helpful in treatment, the presence or absence of psychopathology (e.g., depression, anxiety), and current levels of cognitive functioning.

Comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation is helpful when patients present with cognitive complaints and there is uncertainty about whether psychological factors are contributing to symptoms (e.g., where there is suspected functional cognitive disorder).[67][68][69] It is also useful if there is concern about a differential diagnosis (e.g., epilepsy) that can have cognitive findings. Comprehensive neuropsychological assessment provides detailed evaluation of current cognitive abilities, comparison of abilities in reference to age-adjusted normal control groups, and information on cognitive strengths and weaknesses. Typical findings are either normal cognitive functioning or patterns of nonspecific cognitive abnormalities that differ from neurologic disease.[82] These cognitive findings may be related to multiple factors, including any relevant neurologic history (e.g., history of head injury, learning disability, or attention-deficit disorder), psychopathology or psychological distress, medication effects, and even level of task engagement during the evaluation itself.[82][83][84]

Personality assessment tools commonly used by psychologists include the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2), Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI), and Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-III (MCMI-III).[85][86][87] These are self-report questionnaires completed by patients and interpreted by psychologists with training in standardized assessment. Such assessments should be seen as complements to a comprehensive clinical psychiatric interview and other medical and historical information, as no indicator is 100% sensitive or 100% specific for functional neurologic or somatic symptom disorder.[88]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer