The principles of care for patients with DMD also apply to patients with other muscular dystrophies. Some variations in care are described in this section, and guidelines are available for the care of patients with facioscapulohumeral, limb-girdle, and congenital muscular dystrophies, myotonic dystrophy, and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA).[3]Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Feb;28(2):103-15.

https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(17)31284-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29290580?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Ashizawa T, Gagnon C, Groh WJ, et al. Consensus-based care recommendations for adults with myotonic dystrophy type 1. Neurol Clin Pract. 2018 Dec;8(6):507-20.

https://cp.neurology.org/content/8/6/507

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30588381?tool=bestpractice.com

[13]Tawil R, Kissel JT, Heatwole C, et al. Evidence-based guideline summary: evaluation, diagnosis, and management of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Issues Review Panel of the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Neurology. 2015 Jul 28;85(4):357-64.

https://n.neurology.org/content/85/4/357

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26215877?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Narayanaswami P, Weiss M, Selcen D, et al. Evidence-based guideline summary: diagnosis and treatment of limb-girdle and distal dystrophies: report of the guideline development subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the practice issues review panel of the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Neurology. 2014 Oct 14;83(16):1453-63.

https://n.neurology.org/content/83/16/1453

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25313375?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]Kang PB, Morrison L, Iannaccone ST, et al. Evidence-based guideline summary: evaluation, diagnosis, and management of congenital muscular dystrophy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Issues Review Panel of the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Neurology. 2015 Mar 31;84(13):1369-78.

https://n.neurology.org/content/84/13/1369

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25825463?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Meyer OH, et al; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 2: pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Mar;28(3):197-207.

https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(17)31290-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29305137?tool=bestpractice.com

Multidisciplinary care

There is no cure for DMD. Multidisciplinary care is key, focusing on prolonging function, symptom management, and maintaining a good quality of life for as long as possible. The multidisciplinary team comprises a core team of clinical specialists in neuromuscular, orthopedic, cardiac, and respiratory medicine. It will also include physical therapists, speech therapists, and dietitians for symptom management, as well as occupational therapists, psychologists, and social workers for psychosocial support and to help maximize quality of life and participation. Care coordination (including with primary care providers) and advance planning of transition of care from adolescence to adulthood is vital.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]Duan D, Goemans N, Takeda S, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021 Feb 18;7(1):13.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41572-021-00248-3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33602943?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Fox H, Millington L, Mahabeer I, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. BMJ. 2020 Jan 23;368:l7012.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31974125?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[31]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2018 May;17(5):445-55.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5902408

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398641?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Quinlivan R, Messer B, Murphy P, et al; ANSN. Adult North Star Network (ANSN): consensus guideline for the standard of care of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(6):899-926.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34511509?tool=bestpractice.com

The physical management of DMD, and other muscular dystrophies, is best considered in three stages.

Ambulatory stage: goals include early diagnosis, preservation of muscle strength with the use of corticosteroids (glucocorticoids), reduction of musculotendinous contractures of the extremities, and taking suitable exercise.

Early nonambulatory stage: additional goals include maintenance of optimal nutrition and activities of daily living, and managing scoliosis.

Late nonambulatory stage (usually ventilator-supported): goals include inspiratory and expiratory muscle rest and support.

Common goals of all three stages are prevention of cardiac complications and respiratory management. Psychosocial support for the patient and their family throughout the disease course is essential.

Prevention of cardiac complications

All patients with DMD or Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) develop progressive cardiomyopathy.[33]Tamura T, Shibuya N, Hashiba K, et al. Evaluation of myocardial damage in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy with thallium-201 myocardial SPECT. Jpn Heart J. 1993 Jan;34(1):51-61.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8515572?tool=bestpractice.com

It can be difficult to assess cardiac effects in patients with DMD because the New York Heart Association classification of heart failure relies on reduced exercise tolerance; the signs and symptoms of heart failure in nonambulatory patients may be subtle and so overlooked.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Quinlivan R, Messer B, Murphy P, et al; ANSN. Adult North Star Network (ANSN): consensus guideline for the standard of care of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(6):899-926.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34511509?tool=bestpractice.com

Evidence favors the early treatment of patients with DMD and other dystrophinopathies, but whether such treatment should begin before onset of cardiac symptoms (e.g., reduced left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF]) or evidence of abnormality on imaging is debated.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]El-Aloul B, Altamirano-Diaz L, Zapata-Aldana E, et al. Pharmacological therapy for the prevention and management of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a systematic review. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017 Jan;27(1):4-14.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27815032?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Bourke JP, Bueser T, Quinlivan R. Interventions for preventing and treating cardiac complications in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy and X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct 16;(10):CD009068.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009068.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30326162?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]McNally EM, Kaltman JR, Benson DW, et al. Contemporary cardiac issues in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy. Circulation. 2015 May 5;131(18):1590-8.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.015151

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25940966?tool=bestpractice.com

One analysis of registry data reported that prophylactic ACE inhibitor treatment was associated with a significantly higher overall survival and lower rates of hospitalization for heart failure.[37]Porcher R, Desguerre I, Amthor H, et al. Association between prophylactic angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and overall survival in Duchenne muscular dystrophy - analysis of registry data. Eur Heart J. 2021 May 21;42(20):1976-84.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/42/20/1976/6179515

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33748842?tool=bestpractice.com

Starting patients with DMD on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin-II receptor antagonist by the age of 10 years has been recommended.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Quinlivan R, Messer B, Murphy P, et al; ANSN. Adult North Star Network (ANSN): consensus guideline for the standard of care of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(6):899-926.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34511509?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]McNally EM, Kaltman JR, Benson DW, et al. Contemporary cardiac issues in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy. Circulation. 2015 May 5;131(18):1590-8.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.015151

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25940966?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Feingold B, Mahle WT, Auerbach S, et al. Management of cardiac involvement associated with neuromuscular diseases: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Sep 26;136(13):e200-31.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000526

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28838934?tool=bestpractice.com

Pharmacologic therapy should always be started (if it has not been already) when a patient shows heart failure symptoms or signs of abnormalities on imaging. Typical treatment comprises an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin-II receptor antagonist plus a beta-blocker.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Quinlivan R, Messer B, Murphy P, et al; ANSN. Adult North Star Network (ANSN): consensus guideline for the standard of care of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(6):899-926.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34511509?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]McNally EM, Kaltman JR, Benson DW, et al. Contemporary cardiac issues in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy. Circulation. 2015 May 5;131(18):1590-8.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.015151

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25940966?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Feingold B, Mahle WT, Auerbach S, et al. Management of cardiac involvement associated with neuromuscular diseases: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Sep 26;136(13):e200-31.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000526

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28838934?tool=bestpractice.com

There is some evidence that adjunctive eplerenone (a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist) may provide additional benefit in patients with early cardiomyopathy.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Bourke JP, Bueser T, Quinlivan R. Interventions for preventing and treating cardiac complications in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy and X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct 16;(10):CD009068.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009068.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30326162?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Feingold B, Mahle WT, Auerbach S, et al. Management of cardiac involvement associated with neuromuscular diseases: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Sep 26;136(13):e200-31.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000526

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28838934?tool=bestpractice.com

[39]Raman SV, Hor KN, Mazur W, et al. Eplerenone for early cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2015 Feb;14(2):153-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4361281

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25554404?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Raman SV, Hor KN, Mazur W, et al. Eplerenone for early cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: results of a two-year open-label extension trial. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017 Feb 20;12(1):39.

https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-017-0590-8

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28219442?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with DMD in the late nonambulatory stage are at risk of rhythm abnormalities. These can be treated with standard antiarrhythmic medications or device management. There are no specific recommendations for DMD patients, but guidelines for adults with established heart failure recommend the use of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator for patients with LVEF below 35%.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Feingold B, Mahle WT, Auerbach S, et al. Management of cardiac involvement associated with neuromuscular diseases: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Sep 26;136(13):e200-31.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000526

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28838934?tool=bestpractice.com

Mechanical circulatory support, such as a left ventricular assist device, may be considered if maximal medical management is ineffective. Inherent risks (e.g., thromboembolism, bleeding, infection, device malfunction, right heart failure) and potential benefits must be carefully considered and discussed with the patient.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Feingold B, Mahle WT, Auerbach S, et al. Management of cardiac involvement associated with neuromuscular diseases: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Sep 26;136(13):e200-31.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000526

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28838934?tool=bestpractice.com

Respiratory management

It is rare, but not unheard of, for patients who are ambulatory to develop respiratory failure. Forced vital capacity (FVC) should be measured at least annually in all patients with DMD.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2023 Mar 13;S0012-3692(23)00353-7.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(23)00353-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36921894?tool=bestpractice.com

Soft-tissue contractures of the chest wall and lungs result in diminished lung expansion and, in turn, diminished cough flows, and higher risk of pneumonia and respiratory failure.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2023 Mar 13;S0012-3692(23)00353-7.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(23)00353-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36921894?tool=bestpractice.com

Lung volume recruitment ("air stacking") is indicated when FVC is 60% predicted or less. A self-inflating manual ventilation bag or a mechanical insufflation-exsufflation device is used to provide deep lung inflation beyond the patient's inspiratory capacity once or twice daily.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2023 Mar 13;S0012-3692(23)00353-7.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(23)00353-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36921894?tool=bestpractice.com

Manual and mechanically assisted cough is recommended when FVC is less than 50% predicted, peak cough flow is less than 270 L/minute, or maximum expiratory pressure is less than 60 cm H₂O. Care providers should be trained in these techniques.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Quinlivan R, Messer B, Murphy P, et al; ANSN. Adult North Star Network (ANSN): consensus guideline for the standard of care of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(6):899-926.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34511509?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2023 Mar 13;S0012-3692(23)00353-7.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(23)00353-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36921894?tool=bestpractice.com

During intercurrent respiratory tract infections, the patient's oxyhemoglobin saturation (measured using a pulse oximeter) is maintained above 94% by increasing the frequency of assisted coughing and using noninvasive ventilation as needed.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

Psychosocial support

Comprehensive, lifelong psychosocial care is essential for patients with DMD, other muscular dystrophies, and SMA. It should address social, emotional, and cognitive development, quality of life, and participation. Support for families (parents and siblings) and other caregivers should also be provided.[31]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2018 May;17(5):445-55.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5902408

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398641?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Quinlivan R, Messer B, Murphy P, et al; ANSN. Adult North Star Network (ANSN): consensus guideline for the standard of care of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(6):899-926.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34511509?tool=bestpractice.com

[42]Wang CH, Bonnemann CG, Rutkowski A, et al; International Standard of Care Committee for Congenital Muscular Dystrophy. Consensus statement on standard of care for congenital muscular dystrophies. J Child Neurol. 2010 Dec;25(12):1559-81.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5207780

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21078917?tool=bestpractice.com

People with DMD and other muscular dystrophies have higher rates of intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, depression, and anxiety than the general population, and all patients should be assessed for these conditions. Cognitive and behavioral interventions and medication should be offered as appropriate.[31]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2018 May;17(5):445-55.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5902408

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398641?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Quinlivan R, Messer B, Murphy P, et al; ANSN. Adult North Star Network (ANSN): consensus guideline for the standard of care of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(6):899-926.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34511509?tool=bestpractice.com

If there are concerns about a child's developmental progress, referral for comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation is required, for assessment of cognitive development, academic skills, social functioning, emotional adjustment, and behavioral regulation. Interventions should be offered as needed, with a formal education plan that is reassessed regularly to reflect the child's changing needs and progress.[31]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2018 May;17(5):445-55.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5902408

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398641?tool=bestpractice.com

For the younger child, support for the patient and family focuses on: encouraging goal-oriented activities; discouraging overprotection of the child; addressing possible sibling resentment; facilitating adherence by introducing and planning for future therapeutic options; and setting expectations that patients and their families will actively participate in decisions about their care and daily activities. Additional support may be needed during significant life changes, such as starting or changing school.[31]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2018 May;17(5):445-55.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5902408

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398641?tool=bestpractice.com

Adolescents with DMD have the additional extra burden of severe and progressive disability in addition to the psychological needs of adolescents in general. Patients may benefit from psychotherapy specifically tailored to them from psychologists specialized in their care.[31]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2018 May;17(5):445-55.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5902408

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398641?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]Barnett V, Bach JR. Psychological considerations in the treatment of individuals with generalized neuromuscular disorders. Semin Neurol. 1995 Mar;15(1):58-64.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7638459?tool=bestpractice.com

Adults with DMD (most of whom will be using assisted ventilation) will require ongoing psychosocial support, to maximize their independence, employment potential, and social integration.[31]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2018 May;17(5):445-55.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5902408

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398641?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Quinlivan R, Messer B, Murphy P, et al; ANSN. Adult North Star Network (ANSN): consensus guideline for the standard of care of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(6):899-926.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34511509?tool=bestpractice.com

Ambulatory stage

Early interventions for DMD include starting corticosteroid therapy in order to preserve muscle strength, interventions to prevent or reduce musculotendinous contractures of the extremities, and exercise.

Corticosteroid therapy

All patients with DMD should be offered a corticosteroid. Benefits of long-term corticosteroid therapy include: delaying loss of ambulation; preservation of respiratory function (delaying the need for mechanical ventilation); avoiding or delaying scoliosis surgery; delaying the onset of cardiomyopathy; preservation of upper limb function; and increased survival.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Gloss D, Moxley RT 3rd, Ashwal S, et al. Practice guideline update summary: corticosteroid treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2016 Feb 2;86(5):465-72.

https://n.neurology.org/content/86/5/465

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26833937?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Matthews E, Brassington R, Kuntzer T, et al. Corticosteroids for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 5;(5):CD003725.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003725.pub4/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27149418?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]McDonald CM, Henricson EK, Abresch RT, et al. Long-term effects of glucocorticoids on function, quality of life, and survival in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2018 Feb 3;391(10119):451-61.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29174484?tool=bestpractice.com

It is recommended that corticosteroid therapy is started in young children, before significant physical decline occurs.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]Zhang T, Kong X. Recent advances of glucocorticoids in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (review). Exp Ther Med. 2021 May;21(5):447.

https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/etm.2021.9875

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33777191?tool=bestpractice.com

Prednisone and deflazacort are most often used.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Gloss D, Moxley RT 3rd, Ashwal S, et al. Practice guideline update summary: corticosteroid treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2016 Feb 2;86(5):465-72.

https://n.neurology.org/content/86/5/465

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26833937?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Matthews E, Brassington R, Kuntzer T, et al. Corticosteroids for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 5;(5):CD003725.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003725.pub4/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27149418?tool=bestpractice.com

Deflazacort is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of DMD in patients ages 2 years and older. One review suggested that patients taking deflazacort experience similar or slower rates of functional decline compared with those taking prednisone.[48]Biggar WD, Skalsky A, McDonald CM. Comparing deflazacort and prednisone in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2022;9(4):463-76.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd210776

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35723111?tool=bestpractice.com

There is uncertainty about the optimal corticosteroid dosing regimen for patients with DMD. Some evidence suggests that a weekend-only prednisone regimen is as effective as daily prednisone, with fewer adverse effects.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Gloss D, Moxley RT 3rd, Ashwal S, et al. Practice guideline update summary: corticosteroid treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2016 Feb 2;86(5):465-72.

https://n.neurology.org/content/86/5/465

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26833937?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Matthews E, Brassington R, Kuntzer T, et al. Corticosteroids for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 5;(5):CD003725.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003725.pub4/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27149418?tool=bestpractice.com

Other dosing regimens for prednisone and deflazacort (e.g., every other day; intermittent) have been studied.[47]Zhang T, Kong X. Recent advances of glucocorticoids in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (review). Exp Ther Med. 2021 May;21(5):447.

https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/etm.2021.9875

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33777191?tool=bestpractice.com

A randomized controlled trial reported that daily prednisone or daily deflazacort resulted in significantly better outcomes than intermittent (10 days on/10 days off) prednisone after 3 years' follow-up.[49]Guglieri M, Bushby K, McDermott MP, et al. Effect of different corticosteroid dosing regimens on clinical outcomes in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022 Apr 19;327(15):1456-68.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2790925

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35381069?tool=bestpractice.com

Adverse effects of corticosteroids include truncal obesity and weight gain, osteoporosis and fractures, growth failure with short stature, delayed puberty, and cataracts.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Gloss D, Moxley RT 3rd, Ashwal S, et al. Practice guideline update summary: corticosteroid treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2016 Feb 2;86(5):465-72.

https://n.neurology.org/content/86/5/465

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26833937?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Matthews E, Brassington R, Kuntzer T, et al. Corticosteroids for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 5;(5):CD003725.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003725.pub4/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27149418?tool=bestpractice.com

Prednisone may be associated with greater weight gain than deflazacort, whereas fracture rate, growth failure, and cataract may be worse with deflazacort.[44]Gloss D, Moxley RT 3rd, Ashwal S, et al. Practice guideline update summary: corticosteroid treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2016 Feb 2;86(5):465-72.

https://n.neurology.org/content/86/5/465

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26833937?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]Biggar WD, Skalsky A, McDonald CM. Comparing deflazacort and prednisone in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2022;9(4):463-76.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd210776

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35723111?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients and families should be educated about these adverse effects and interventions to address them.

Before starting corticosteroid therapy, guidance for weight management should be provided. Supplements, especially vitamin D and calcium, should be added early in the course.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Quinlivan R, Messer B, Murphy P, et al; ANSN. Adult North Star Network (ANSN): consensus guideline for the standard of care of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(6):899-926.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34511509?tool=bestpractice.com

Corticosteroids have not been shown to be useful for other muscular dystrophies, but evidence is limited due to the rare nature of these disorders.[50]Quattrocelli M, Zelikovich AS, Salamone IM, et al. Mechanisms and clinical applications of glucocorticoid steroids in muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(1):39-52.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200556

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33104035?tool=bestpractice.com

Prevention or reduction of musculotendinous contractures

Ambulation is impaired by the combination of muscle weakness and musculotendinous contractures. To minimize joint contractures, a home stretching program focusing on the ankles, knees, and hips should be started, under the guidance of a physical therapist.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

Molded ankle-foot orthoses may be used for stretching at night.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

Surgery is recommended less frequently than it was in the past for treating contractures in patients with DMD. If a patient has substantial ankle contracture with good quadriceps and hip extensor strength, surgery on the foot and Achilles tendon is recommended to improve gait in carefully selected cases. Surgical interventions related to the hips and knees are not recommended.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

Surgical interventions may be more effective for prolonging brace-free ambulation for patients with milder muscular dystrophies, such as BMD and Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy.

Exercise

Regular submaximal aerobic activity or exercise is beneficial. Recommended exercise for people with DMD includes swimming and cycling (with assistance as needed). High-resistance exercise or strength training should be avoided, because of the risk of muscle damage and metabolic abnormalities. Exercise should be guided and monitored by a physical therapist.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

One Cochrane review concluded that evidence about the benefits of strength training and aerobic exercise interventions for improving muscle and cardiorespiratory function in DMD remains uncertain.[51]Voet NB, van der Kooi EL, van Engelen BG, et al. Strength training and aerobic exercise training for muscle disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Dec 6;(12):CD003907.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003907.pub5/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31808555?tool=bestpractice.com

For patients with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, aerobic exercise training may increase aerobic capacity.[51]Voet NB, van der Kooi EL, van Engelen BG, et al. Strength training and aerobic exercise training for muscle disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Dec 6;(12):CD003907.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003907.pub5/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31808555?tool=bestpractice.com

Muscular exercise was associated with modest improvements in endurance during walking in patients with facioscapulohumeral and myotonic dystrophy in one meta-analysis, but did not improve muscle strength.[52]Gianola S, Castellini G, Pecoraro V, et al. Effect of muscular exercise on patients with muscular dystrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Front Neurol. 2020;11:958.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2020.00958/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33281695?tool=bestpractice.com

Early nonambulatory stage

Corticosteroid therapy, physical therapy, and exercise (with assistance as needed) should continue.

Maintenance of activities of daily living (useful for all muscular dystrophies)

Assistive technology, adaptive devices, and mobility aids should be provided to help patients optimize function, and maintain activities of daily living, participation, and quality of life.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients benefit from the use of a standard and/or a motorized wheelchair.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

Standing motorized wheelchairs help maintain bone and articular integrity, and optimize psychological outlook. A trial of a standing motorized wheelchair is suitable for patients who are motivated to stand, have tolerance and comfort in supported standing for at least 10 minutes, and have ankle contracture of less than 10 degrees.[53]Schofield C, Evans K, Young H, et al. The development of a consensus statement for the prescription of powered wheelchair standing devices in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Disabil Rehabil. 2022 May;44(10):1889-97.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32878485?tool=bestpractice.com

Molded ankle-foot orthotics may be beneficial for stretching or positioning during the day, and decreasing the rate of musculotendinous contracture development.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

[54]Rose KJ, Burns J, Wheeler DM, et al. Interventions for increasing ankle range of motion in patients with neuromuscular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Feb 17;(2):CD006973.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006973.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20166090?tool=bestpractice.com

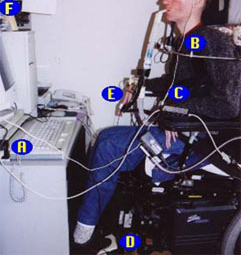

Robotic arms exist that are programmable, portable, and adaptable to various surfaces and applications. They can assist with most upper limb activities. Computers for environmental control and lower limb resting splints may be beneficial.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 47-year-old man with Duchenne muscular dystrophy showing use of a computer for environmental control: A) joystick adapter that lets patient use computer games; B) mini-joystick; C) device that allows patient to use 5 single switches to operate any device that accepts 1 multiple switch; D) platform switch activated by pressing down on raised pad; E) microlight activated by pressing on top surface with feather-light touch; F) head-pointing device that allows patient to move a cursor by moving their headFrom the collection of John R. Bach, MD, FAAPMR; used with permission [Citation ends].

Management of scoliosis

Patients treated with corticosteroids typically have milder spinal curvature than untreated patients, reducing the need for scoliosis surgery.[11]Duan D, Goemans N, Takeda S, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021 Feb 18;7(1):13.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41572-021-00248-3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33602943?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[55]Cheuk DK, Wong V, Wraige E, et al. Surgery for scoliosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Oct 1;(10):CD005375.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005375.pub4/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26423318?tool=bestpractice.com

However, spinal curvature should still be monitored regularly in all patients with DMD, as scoliosis can develop at a later age.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

If significant scoliosis is present, the patient may be referred for posterior spinal fusion. The decision whether or not to offer surgery will depend on factors such as the age, skeletal maturity, and general health of the patient, and the extent of the spinal curve and how quickly the scoliosis is worsening. Progression of scoliosis in patients on corticosteroids is less predictable, so observation for evidence of progression is reasonable before intervention.[11]Duan D, Goemans N, Takeda S, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021 Feb 18;7(1):13.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41572-021-00248-3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33602943?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

Spinal orthoses are not recommended.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

Late nonambulatory stage (usually ventilator-supported)

Ventilatory support for all muscular dystrophies

Patients in the late nonambulatory stage need assisted ventilation to prolong survival. Noninvasive ventilation is introduced for patients who are symptomatic for nocturnal hypoventilation with some combination of fatigue, morning headaches, daytime drowsiness, frequent nocturnal awakenings, and dyspnea. Some patients with DMD do not show symptoms of hypoventilation, so nocturnal noninvasive ventilation is also recommended when a patient has FVC below 50% predicted or maximum inspiratory pressure below 60 cm H₂O. Abnormal sleep studies (e.g., overnight oximetry, combination oximetry-capnography, and polysomnography with capnography) may also indicate a need for nocturnal ventilation. Nasal or oronasal noninvasive ventilation is used for nocturnal support.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2023 Mar 13;S0012-3692(23)00353-7.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(23)00353-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36921894?tool=bestpractice.com

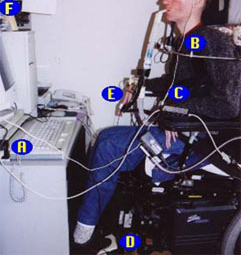

As patients require more ventilatory support, they extend noninvasive ventilation into daytime hours. Guidelines support the use of noninvasive assisted ventilation for up to 24 hours a day. Indications for daytime assisted ventilation include: blood oxyhemoglobin saturation by pulse oximetry (SpO₂) below 95%, partial pressure of CO₂ above 45 mmHg, or symptoms of dyspnea when awake. A mouthpiece is more commonly used during daytime hours, but nasal ventilation may be preferred by some patients, and is needed for patients whose lips cannot hold a mouthpiece.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2023 Mar 13;S0012-3692(23)00353-7.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(23)00353-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36921894?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 47-year-old man with Duchenne muscular dystrophy using a 15 mm angled mouthpiece for daytime ventilatory supportFrom the collection of John R. Bach, MD, FAAPMR; used with permission [Citation ends].

Combination of noninvasive assisted ventilation with manual and mechanically assisted cough as needed is highly effective at prolonging life, and tracheostomy is not usually required. Indications for tracheostomy include: patient preference, inability to use noninvasive ventilation (e.g., due to cognitive impairment), three failed extubation attempts during a critical illness despite optimum use of noninvasive ventilation and mechanically assisted cough, or failure of noninvasive methods of cough assistance to prevent aspiration.[30]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Apr;17(4):347-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889091

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395990?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2023 Mar 13;S0012-3692(23)00353-7.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(23)00353-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36921894?tool=bestpractice.com

Diaphragm pacing should not be used for patients with muscular dystrophies because it is ineffective and may be harmful.[56]Mahajan KR, Bach JR, Saporito L, et al. Diaphragm pacing and noninvasive respiratory management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Muscle Nerve. 2012 Dec;46(6):851-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23042087?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]DiPALS Writing Committee; DiPALS Study Group Collaborators. Safety and efficacy of diaphragm pacing in patients with respiratory insufficiency due to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (DiPALS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2015 Sep;14(9):883-92.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laneur/article/PIIS1474-4422(15)00152-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26234554?tool=bestpractice.com

Maintenance of optimal nutrition

An indwelling gastrostomy tube is required for patients who cannot swallow safely, or who cannot maintain adequate nutrition or hydration despite other interventions.[10]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Mar;17(3):251-67.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5869704

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29395989?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Quinlivan R, Messer B, Murphy P, et al; ANSN. Adult North Star Network (ANSN): consensus guideline for the standard of care of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(6):899-926.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34511509?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatments for SMA

Many of the principles for management of SMA are similar to those for managing muscular dystrophies. Several drugs are available.

Pharmacologic treatment

Nusinersen is an antisense oligonucleotide that can be used to treat patients with SMA. It is approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the FDA. One Cochrane review concluded that intrathecal nusinersen improves motor function in patients with SMA type 2, based on moderate‐certainty evidence.[58]Wadman RI, van der Pol WL, Bosboom WM, et al. Drug treatment for spinal muscular atrophy types II and III. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Jan 6;(1):CD006282.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006282.pub5/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32006461?tool=bestpractice.com

Subsequent studies reported improved or stabilized motor function in patients with SMA type 2 or 3 after 12-24 months of treatment with nusinersen.[59]Pane M, Coratti G, Pera MC, et al; Italian ISMAC group. Nusinersen efficacy data for 24-month in type 2 and 3 spinal muscular atrophy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022 Mar;9(3):404-9.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acn3.51514

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35166467?tool=bestpractice.com

[60]Coratti G, Pane M, Lucibello S, et al; iSMAC group. Age related treatment effect in type II spinal muscular atrophy pediatric patients treated with nusinersen. Neuromuscul Disord. 2021 Jul;31(7):596-602.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34099377?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Pechmann A, Behrens M, Dörnbrack K, et al; SMArtCARE study group. Improved upper limb function in non-ambulant children with SMA type 2 and 3 during nusinersen treatment: a prospective 3-years SMArtCARE registry study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022 Oct 23;17(1):384.

https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-022-02547-8

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36274155?tool=bestpractice.com

One Cochrane review concluded that nusinersen probably prolongs ventilation‐free and overall survival in infants with SMA type 1, and that a greater proportion of infants treated with nusinersen than with a sham procedure achieve motor milestones and may be classed as responders.[62]Wadman RI, van der Pol WL, Bosboom WM, et al. Drug treatment for spinal muscular atrophy type I. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Dec 11;(12):CD006281.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006281.pub5/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31825542?tool=bestpractice.com

Communicating hydrocephalus (not related to meningitis or bleeding) has been reported in some people during treatment with nusinersen. Most cases developed after 2-4 loading doses. The UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) recommends prompt investigation of any case suggestive of communicating hydrocephalus in patients treated with nusinersen, informing patients about the signs and symptoms of communicating hydrocephalus before starting treatment, and advising patients to seek urgent medical attention should any possible symptoms or signs develop.[63]Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Nusinersen (Spinraza▼): reports of communicating hydrocephalus; discuss symptoms with patients and carers and investigate urgently. Sep 2018 [internet publication].

https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/nusinersen-spinraza-reports-of-communicating-hydrocephalus-discuss-symptoms-with-patients-and-carers-and-investigate-urgently

Onasemnogene abeparvovec is a gene therapy for children under 2 years of age with SMA type 1. It is approved by the EMA and the FDA. A one-time intravenous administration of onasemnogene abeparvovec results in expression of the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein in a child's motor neurons, and has been reported to improve event-free survival, motor function, and motor milestone outcomes for up to 5 years.[64]Day JW, Finkel RS, Chiriboga CA, et al. Onasemnogene abeparvovec gene therapy for symptomatic infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy in patients with two copies of SMN2 (STR1VE): an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021 Apr;20(4):284-93.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33743238?tool=bestpractice.com

[65]Mendell JR, Al-Zaidy SA, Lehman KJ, et al. Five-year extension results of the phase 1 START trial of onasemnogene abeparvovec in spinal muscular atrophy. JAMA Neurol. 2021 Jul 1;78(7):834-41.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/fullarticle/2780250

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33999158?tool=bestpractice.com

[66]Mercuri E, Muntoni F, Baranello G, et al; STR1VE-EU study group. Onasemnogene abeparvovec gene therapy for symptomatic infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (STR1VE-EU): an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021 Oct;20(10):832-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34536405?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]Blair HA. Onasemnogene abeparvovec: a review in spinal muscular atrophy. CNS Drugs. 2022 Sep;36(9):995-1005.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40263-022-00941-1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35960489?tool=bestpractice.com

[68]Weiß C, Ziegler A, Becker LL, et al. Gene replacement therapy with onasemnogene abeparvovec in children with spinal muscular atrophy aged 24 months or younger and bodyweight up to 15 kg: an observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022 Jan;6(1):17-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34756190?tool=bestpractice.com

There is a risk of hepatotoxicity and thrombotic microangiopathy. Fatal cases of acute liver failure have been reported, and liver function should be monitored before and after treatment.

Risdiplam is an SMN2-directed RNA splicing modifier for the treatment of SMA in adults and children. It is approved by the EMA and the FDA. It is the first orally administered treatment that patients can take at home. In trials including patients from age 1 month, risdiplam was associated with clinically meaningful improvements in motor function and achievement of developmental milestones in patients with SMA type 1, 2, or 3 , and increased expression of functional SMN protein in patients with SMA type 1.[69]Baranello G, Darras BT, Day JW, et al; FIREFISH Working Group. Risdiplam in type 1 spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2021 Mar 11;384(10):915-23.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2009965

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33626251?tool=bestpractice.com

[70]Mercuri E, Deconinck N, Mazzone ES, et al; SUNFISH Study Group. Safety and efficacy of once-daily risdiplam in type 2 and non-ambulant type 3 spinal muscular atrophy (SUNFISH part 2): a phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022 Jan;21(1):42-52.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34942136?tool=bestpractice.com

Improvements for patients with SMA type 1 have been recorded over 24 months.[71]Masson R, Mazurkiewicz-Bełdzińska M, Rose K, et al; FIREFISH Study Group. Safety and efficacy of risdiplam in patients with type 1 spinal muscular atrophy (FIREFISH part 2): secondary analyses from an open-label trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022 Dec;21(12):1110-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36244364?tool=bestpractice.com

Symptom management

The different forms of SMA have different degrees of severity, and guidelines provide recommendations for nonsitters, sitters, and walkers.[3]Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Feb;28(2):103-15.

https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(17)31284-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29290580?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Meyer OH, et al; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 2: pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Mar;28(3):197-207.

https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(17)31290-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29305137?tool=bestpractice.com

Stretching and positioning: modalities include using orthoses, splints, active-assistive and passive methods, supported supine/sitting/standing frames, serial casting, and use of postural supports.[3]Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Feb;28(2):103-15.

https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(17)31284-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29290580?tool=bestpractice.com

Airway clearance is by manual chest physical therapy plus mechanical insufflation-exsufflation. Noninvasive ventilation is recommended for all symptomatic nonambulatory children. It is also recommended for nonsitters before signs of respiratory failure are apparent.[29]Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Meyer OH, et al; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 2: pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Mar;28(3):197-207.

https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(17)31290-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29305137?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2023 Mar 13;S0012-3692(23)00353-7.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(23)00353-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36921894?tool=bestpractice.com

Mobility and exercise: power assist and manual wheelchairs with postural support maximize mobility. Exercise is tailored to the ability of the patient, and may include aquatic therapy, aerobic and general conditioning exercise with and without resistance, and balance exercise.[3]Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Feb;28(2):103-15.

https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(17)31284-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29290580?tool=bestpractice.com

One Cochrane review concluded that it is uncertain whether combined strength and aerobic exercise training is beneficial or harmful for people with SMA type 3.[72]Bartels B, Montes J, van der Pol WL, et al. Physical exercise training for type 3 spinal muscular atrophy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Mar 1;(3):CD012120.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD012120.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30821348?tool=bestpractice.com

Management of spine deformity and contractures: scoliosis is common in patients with SMA type 1 or 2. Spinal orthoses may be used initially, but surgery is often required. Contractures are managed with stretching and orthoses.[3]Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Feb;28(2):103-15.

https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(17)31284-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29290580?tool=bestpractice.com

Other complications of SMA that may require management include cardiac symptoms, dysphagia, weight control, and growth failure.[3]Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Feb;28(2):103-15.

https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(17)31284-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29290580?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Meyer OH, et al; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 2: pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Mar;28(3):197-207.

https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(17)31290-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29305137?tool=bestpractice.com

Palliative and end-of-life care

Early neuropalliative care consultation is recommended. Patients should be supported using the principles of palliative care and, in particular, the use of a holistic approach to support patients and their families throughout the illness course. Key components of palliative care include informed goals-of-care discussions, advance directive planning, symptom management, and end-of-life support.[22]Fox H, Millington L, Mahabeer I, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. BMJ. 2020 Jan 23;368:l7012.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31974125?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Meyer OH, et al; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 2: pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Mar;28(3):197-207.

https://www.nmd-journal.com/article/S0960-8966(17)31290-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29305137?tool=bestpractice.com

[31]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2018 May;17(5):445-55.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5902408

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398641?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Quinlivan R, Messer B, Murphy P, et al; ANSN. Adult North Star Network (ANSN): consensus guideline for the standard of care of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021;8(6):899-926.

https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-neuromuscular-diseases/jnd200609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34511509?tool=bestpractice.com

[73]Taylor LP, Besbris JM, Graf WD, et al. Clinical guidance in neuropalliative care: an AAN position statement. Neurology. 2022 Mar 8;98(10):409-16.

https://n.neurology.org/content/98/10/409

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35256519?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Andrews JG, Wahl RA. Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy in adolescents: current perspectives. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2018 Mar 15;9:53-63.

https://www.dovepress.com/duchenne-and-becker-muscular-dystrophy-in-adolescents-current-perspect-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-AHMT

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29588625?tool=bestpractice.com

Advance directives and wishes for end-of-life care should be discussed with the patient and family/caregivers as early as possible, long before hospice care is needed, and should be an ongoing conversation.[31]Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al; DMD Care Considerations Working Group. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 3: primary care, emergency management, psychosocial care, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2018 May;17(5):445-55.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5902408

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29398641?tool=bestpractice.com

[73]Taylor LP, Besbris JM, Graf WD, et al. Clinical guidance in neuropalliative care: an AAN position statement. Neurology. 2022 Mar 8;98(10):409-16.

https://n.neurology.org/content/98/10/409

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35256519?tool=bestpractice.com