Approach

Optic neuritis (ON) diagnosis is made clinically and there is no established diagnostic criteria.[3] In an acute setting, a clinician’s primary predicament is identifying if the cause is infectious or systemic (usually monophasic), or if it is autoimmune (usually relapsing). However, this can overlap.

A careful history with both ophthalmologic and neurologic exams are important, taking into account current and previous symptoms. Clinical presentation will likely differ depending on when the patient is seen so it is important to clarify if a patient is in acute (<7 days), subacute (1 week to 3 months), or chronic phase (>3 months), and if this is a first or recurrent attack.[3] A first attack of ON may be linked to 60 or more different disorders or ON may occur at any time during other disorders.[3] Many causes of monocular visual loss can mimic ON which can lead to wrong and delayed treatment causing catastrophic visual outcome.[3][19]

The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) describes a diagnostic approach focusing on the following factors in the history and examination when considering a diagnosis of ON:[12]

History:

Acute visual loss (typically progressive over <7 days)

Monocular (typically)

Periorbital pain (initially, in majority), often increased with eye movement (resolves in 1-2 weeks)

Demyelinating symptoms or known MS diagnosis (possibly)

Clinical features:

Decreased visual acuity

Decreased color vision (often out of proportion to acuity loss)

Visual field defect (diffuse, altitudinal, cecocentral or other)

Relative afferent pupillary defect (if unilateral or asymmetric)

⅔ normal disc appearance (retrobulbar), ⅓ disc edema (bulbar or papillitis); if present, disc edema is typically mild without hemorrhage or exudates

History

ON classically presents as painful monocular visual impairment or loss coming on over several days and reaches a nadir at 1 to 2 weeks. Pain is periorbital and worsened by eye movement; it is more common when ON is retrobulbar. Patients may describe Uhthoff phenomenon (worsening of symptoms with increases in body temperature, e.g., while jogging) or Pulfrich phenomenon (altered depth perception of moving objects). Phosphenes (positive visual phenomena) may be reported, especially in the acute phase.

In the diagnosis of ON, it is important to elicit any personal history of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), sarcoidosis, and Behcet disease. It is also important to inquire about history of infectious diseases: in particular, Lyme disease or syphilis. A history of inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis is also important, in particular with regard to prior treatment due to the rare occurrence of ON in recipients of anti-TNF biologicals.

Most importantly, the patient should be asked about prior episodes of ON and about prior neurologic symptoms compatible with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (MS). Previous similar ophthalmologic events may represent prior attacks of ON but need not be of similar intensity and may not be given much attention at the time. Previous neurologic events should not be given in an open-ended question to the patient but a list of possible symptoms offered, including sensory, balance, gait, motor, or sphincter disturbances. This will help determine whether the ON is a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) or part of MS.

Importance should be given to the timing and severity of ON symptoms. Recent events such as viral infection or vaccination must be noted.

Physical exam

Ophthalmologic exam shows various degrees of decreased visual acuity, color perception, contrast sensitivity, and visual field. There is a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) in more than 90% of cases. RAPD is an asymmetry of pupillomotor input between the 2 eyes. It is detected clinically by alternating a light between the eyes and observing a decrease in the direct light reaction of the affected eye. RAPD represented a diagnostic criterion for the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial (ONTT).[20] In about one third of cases there is swelling of the optic disk on fundoscopy (papillitis), while in the remaining two-thirds the disk looks normal. Pallor of optic disk indicating optic atrophy is a sign of previous ON. In the ONTT, one third had visual acuities of 20/200 or worse, 10% 20/20 or better, and the rest had values in between. More detailed ophthalmologic exam may reveal perivenous retinal sheathing. Visual field defects can take any form, with diffuse defects being most commonly encountered and the classically described central or centrocecal scotoma being present in only 8% of cases.[2]

Neurologic exam may be normal in cases of ON occurring in isolation (CIS), or may show subtle abnormalities such as mild sensory loss or internuclear ophthalmoplegia when the CIS has polysymptomatic presentation. More obvious neurologic deficits may be noted on neurologic examination when the ON is part of established MS.

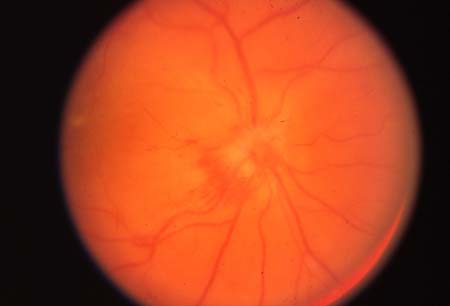

Rarely, ON is a manifestation of other systemic inflammatory diseases, and the examination needs to be context-specific, looking for evidence of other manifestations of diseases such as SLE, sarcoidosis, or Lyme disease.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Papillitis in optic neuritisFrom the personal collections of Dr Cris S. Constantinescu and Dr Thomas M. Bosley [Citation ends].

Clinical investigations

Advances in investigations for ON are related to an increased precision of autoantibody related diagnosis, improved accuracy of neuroimaging, and increased recognition of the value of retinal optical coherence tomography (OCT) for diagnosis and monitoring.[3]

Clinicians should be aware of unilateral or bilateral conditions which mimic acute ON and consider the use of multimodal retinal imaging (e.g., high-resolution OCT) to rule out other diagnoses.[21] Any mismatch from what is expected from the natural disease course needs to be explained, requires additional investigation, noting red flags for alternative diagnosis or urgent treatment. This will help with working out which ON subtypes are present.[3]

If the patient has an existing MS diagnosis and the ON case is typical, no further testing is usually required.[12]

MRI

MRI can provide prognostic information in monosymptomatic or clinically isolated syndrome cases (first episode of demyelination) and future risk of MS.[12]

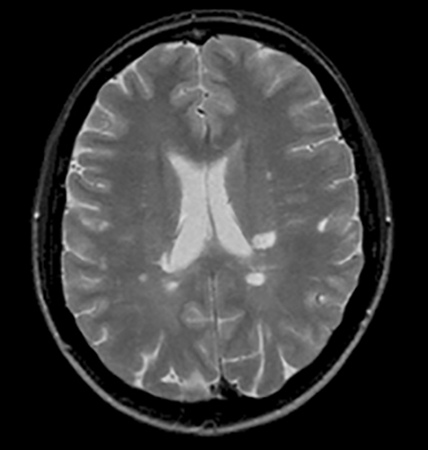

In acute ON, gadolinium-enhanced MRI shows enhancing lesions in the optic nerve. The optic nerve may show various degrees of swelling.[22] When in the context of MS, typical white matter hyperintense lesions in the brain parenchyma, with a predominantly periventricular location, may reflect the established diagnosis of MS. When such lesions are seen in a patient whose ON is the first neurologic event (CIS), there is a substantial risk of recurrence and thus conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis (CDMS).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Transverse MRI showing typical white matter periventricular hyperintense lesions in the brain parenchymaFrom the personal collections of Dr Cris S. Constantinescu and Dr Thomas M. Bosley [Citation ends].

Other investigations

In addition to MRI, CBC, ESR, C-reactive protein, VDRL, uric acid, serum angiotensin-converting enzyme, ANA, B12, and folate, aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibody, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody, and collapsin response mediator protein 5 (CRMP5) antibody are routinely done at the time of the initial presentation, to rule out causes other than idiopathic demyelinating ON.

Other optional testing that may be done, based on the clinical presentation and degree of uncertainty regarding the diagnosis of ON (and MS), includes:

Lyme titer testing for Borrelia burgdorferi should be ordered in endemic areas or otherwise in special circumstances (e.g., history of tick bite, erythema chronicum migrans).

Visual-evoked potentials (VEP) of the affected eye show delayed latency of the P100 wave (the first positive wave of the VEP, which appears normally with a latency of about 100 ms) compared to the unaffected eye. P100 latency remains prolonged for a long time, even after color vision and visual fields normalize, making VEP useful for the retrospective diagnosis of past ON.[23] Multifocal VEPs are also helpful in distinguishing ON as part of CDMS from ON in patients with conditions other than MS, as they tend to be more abnormal in CDMS-associated ON.[24]

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis may help diagnostically in ruling out other causes of optic neuropathies and establishing the inflammatory nature of an optic neuropathy. Prognostically, positive oligoclonal bands or high IgG index help in establishing the risk of conversion to CDMS after a CIS of ON; however, CSF analysis is usually not necessary for predicting conversion to CDMS.[25][26] It should be noted that CSF analysis is a sensitive but not highly specific test for primary demyelinating disease, and that conversely the CSF is normal in 10% to 20% of MS cases. Due to the invasive nature of lumbar puncture, all other noninvasive tests should be pursued first.[27]

Fluorescein angiography may show leakage of fluorescein from the affected optic disk or retinal vessels, denoting some degree of papillitis or retinal vasculitis.

OCT is a technique that quantifies the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness. The peripapillary RNFL (pRNFL) is particularly relevant. This is a good measure of axonal integrity, and axonal loss in acute ON predicts the degree of visual recovery.[28] MS patients have reduced RNFL thickness even in the absence of previous ON. This can be monitored over time. The thickness of the macular ganglion cell/inner plexiform layer (mGCIPL) also seems to be a good prognosis indicator for outcome.[29]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer