History and exam

Key diagnostic factors

common

family history of vision loss

Inherited retinal conditions should always be considered in a patient complaining of night blindness, especially when there is a family history of similar complaints.[4]

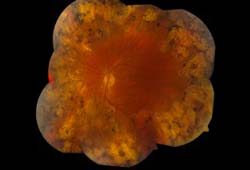

history of retinitis pigmentosa

Condition associated with night blindness. One of the most common inherited retinal disorders.[6][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Retinitis pigmentosa as seen on fundoscopyProvided by Hugh Harris, Sunderland Eye Infirmary, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

Patients can present complaining of night blindness at variable ages depending on the mode of inheritance.[3]

Retinitis pigmentosa can occur as part of systemic syndromes, such as Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome and Refsum disease. Dietary modifications, such as reduction of phytanic acid intake in Refsum disease, can slow the progression of the systemic and retinal disease seen in these syndromes.[8]

uncommon

congenital stationary night blindness

Comprises a group of inherited disorders that present in childhood and are characterized by poor night vision.[6]

past medical history of vitamin A deficiency or malignancy

Xerophthalmia refers to the spectrum of ocular manifestations due to vitamin A deficiency. Common ocular manifestations of vitamin A deficiency include conjunctival xerosis, bitot spots, corneal ulceration, and keratomalacia, with the most severe forms of keratomalacia including corneal edema and corneal melt. The xerophthalmic fundus may present with small, white, deep retinal lesions throughout the posterior pole.[25]

Night blindness is generally the earliest clinical manifestation of xerophthalmia and is both sensitive and specific for low serum retinol levels.[10]

Xerophthalmia is more common in resource-poor countries due to poor intake of vitamin A, with particularly high mortality rates in malnourished children.[11][12]

Conditions that may cause vitamin A deficiency include cystic fibrosis, pancreatic insufficiency, Crohn disease, and previous gastric surgery.[2] Certain medications, particularly retinoic acid derivatives, may also cause symptomatic vitamin A deficiency.[13]

A history of malignancy, particularly cutaneous malignant melanoma, should also be determined.

Other diagnostic factors

common

decreased visual acuity in dim light

Visual acuity should be checked using a Snellen chart. The level of acuity may vary depending on the underlying cause and the extent of retinal or choroidal disease.

variable pupillary responses (depending on underlying cause)

Pupil examination is a key part of the ophthalmic exam and should not be forgotten. Check pupillary responses in any patient complaining of visual disturbance. However, because pupil reflexes vary according to the condition and level of severity, expected responses cannot be specified.

retinal vascular attenuation

visual field loss

Constriction of the peripheral visual fields on confrontational testing may be present in patients complaining of night blindness.[3]

peripheral chorioretinal degeneration

Fundal examination may reveal peripheral retinal or choroidal changes found in inherited conditions that cause night blindness.[3]

uncommon

history of drugs that interfere with vitamin A metabolism

Drugs that interfere with vitamin A metabolism (e.g., retinoic acid derivatives) can cause night blindness.

Risk factors

strong

retinitis pigmentosa

A common inherited retinal disorder, retinitis pigmentosa can also occur as part of other systemic syndromes, including Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome and Refsum disease.[6] Retinitis pigmentosa can be inherited in an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked manner.[7] Genetic testing can be offered to patients for family planning.

Depending on the mode of inheritance, patients can present with night blindness at different ages.[3] Dietary modifications, such as reduction of phytanic acid intake in retinitis pigmentosa, can slow the progression of the systemic and retinal disease seen in these syndromes.[8]

congenital stationary night blindness

Congenital stationary night blindness is a nonprogressive condition. It comprises a group of inherited disorders that present in childhood and are characterized by poor night vision.[6] Patients may present with night blindness, nystagmus, normal vision, or poor vision (as low as 20/200). The fundi may appear normal or abnormal, and the diagnosis is usually confirmed by genetic testing and electroretinography.[9]

vitamin A deficiency

Xerophthalmia refers to the spectrum of ocular manifestations due to vitamin A deficiency. Night blindness is generally the earliest clinical manifestation of xerophthalmia, and is both sensitive and specific for low retinol levels.[10] Xerophthalmia is more common in resource-poor countries due to inadequate dietary intake of vitamin A, and is associated with high mortality rates in malnourished children.[11][12]

Conditions that may cause vitamin A deficiency include cystic fibrosis, pancreatic insufficiency, Crohn disease, and previous gastric surgery.[2] Certain medications, particularly retinoic acid derivatives, may also cause symptomatic vitamin A deficiency.[13] See Primary prevention.

weak

cancer-associated retinopathy

A rare autoimmune condition associated with several cancers, but particularly, small cell lung cancer. Patients may present with varying visual phenomena (e.g., flashes or scotomas) including night blindness.[5]

melanoma-associated retinopathy

This condition may present with night blindness in patients who have a history of cutaneous malignant melanoma.[14]

gyrate atrophy

An autosomal recessive condition in which progressive outer chorioretinal atrophy reduces night vision and progresses to blindness. Hyperornithinemia occurs in these patients, although the exact mechanism of chorioretinal atrophy is not fully understood.[15] An arginine-restricted diet and treatment with pyridoxine (vitamin B6) can help slow disease progression.[8]

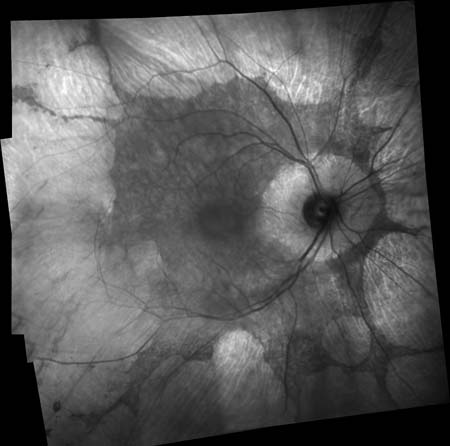

choroideremia

This X-linked recessive condition may present with variable visual symptoms including night blindness.[16][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Choroideremia as seen on fundoscopyProvided by Hugh Harris, Sunderland Eye Infirmary, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer