It is important to detect neck pain caused by significant causes (e.g., primary or metastatic cancer) and neck pain associated with neurologic compromise. The diagnostic approach to neck pain has not been as well studied as back pain, but a similar approach is recommended.

Traumatic neck pain: initial evaluation and imaging

The risk for cervical spine injury needs to be assessed in patients presenting acutely with neck pain following trauma. The presenting clinical features and mechanism of injury should be considered when assessing risk for cervical spine injury. High risk criteria include the following:[34]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: acute spinal trauma. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69359/Narrative

[50]Stiell IG, Clement CM, McKnight RD, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. N Engl J Med. 2003 Dec 25;349(26):2510-8.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa031375

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14695411?tool=bestpractice.com

[51]Vandemark RM. Radiology of the cervical spine in trauma patients: practice pitfalls and recommendations for improving efficiency and communication. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990 Sep;155(3):465-72.

https://www.ajronline.org/doi/abs/10.2214/ajr.155.3.2117342

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2117342?tool=bestpractice.com

Age >65 years

Paresthesias in extremities

Altered mental status

Multiple fractures

Drowning or diving accident

Significant head or facial injury

Dangerous mechanism,” defined as: a fall from an elevation of 3 feet (90 cm) or more, or 5 stairs; axial load to the head (e.g., diving), motor vehicle collision at high speed (>60 mph or >100 km/h) or with rollover or ejection; collision involving a motorized recreational vehicle; or a bicycle collision.

Immobilization of the cervical spine must be maintained in all patients with suspected cervical spine injury until cleared either clinically or radiologically. In trauma patients who have their necks stabilized with a cervical collar, hypotension, tachycardia, and hypoxia are signs of significant trauma and should be evaluated thoroughly.

Screening imaging must be done before any neck movement exam. A cervical spine computed tomography (CT) scan is the study of choice for suspected cervical spine injury in the setting of multisystem trauma or with a high-risk mechanism.[34]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: acute spinal trauma. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69359/Narrative

[41]Cain GS, Shepherdson J, Elliott V, et al. Imaging suspected cervical spine injury: plain radiography or computed tomography? systematic review. Radiography. 2010;16(1):68-77.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1078817409000698

[52]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

Cervical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be ordered in addition to cervical CT scan when ligamentous injury is suspected, or if neurologic signs and symptoms referable to the cervical spine are present.[34]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: acute spinal trauma. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69359/Narrative

[52]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

[53]Schoenfeld AJ, Bono CM, McGuire KJ, et al. Computed tomography alone versus computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the identification of occult injuries to the cervical spine: a meta-analysis. J Trauma. 2010 Jan;68(1):109-13;discussion 113-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20065765?tool=bestpractice.com

Guidelines advise that cervical spine CT scan alone can be used to exclude cervical spine injuries in obtunded or intubated patients without neurologic evidence to the contrary.[54]Plumb JOM. Clinical review: Spinal imaging for the adult obtunded blunt trauma patient: update from 2004. Intensive Care Med. 2012 May;38(5):752-71.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22407141?tool=bestpractice.com

[55]Panczykowski DM, Tomycz ND, Okonkwo DO, et al. Comparative effectiveness of using computed tomography alone to exclude cervical spine injuries in obtunded or intubated patients: meta-analysis of 14,327 patients with blunt trauma.J Neurosurg. 2011 Sep;115(3):541-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21619408?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]British Orthopaedic Association. BOAST - cervical spine clearance in the trauma patient. May 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.boa.ac.uk/resource/boast-cervical-spine-clearance-in-the-trauma-patient.html

Cervical spine x-rays may be performed in patients rather than CT scan following trauma when the injury is less severe, high risk criteria are not met, and there are no other features making exam findings less reliable (e.g., alcohol intoxication, painful distracting injuries). No further imaging is required in the following cases:[41]Cain GS, Shepherdson J, Elliott V, et al. Imaging suspected cervical spine injury: plain radiography or computed tomography? systematic review. Radiography. 2010;16(1):68-77.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1078817409000698

Clinical decision rules have been proposed to help physicians working in emergency care settings be more selective about when to use cervical spine radiography to assess alert and stable trauma patients.

Canadian C-spine rule

Applied in less severely injured patients, and may eliminate the need for any radiography. The rule must be properly applied and it does not pertain to a patient over the age of 65.[57]Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen KL, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA. 2001 Oct 17;286(15):1841-8.

https://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/286/15/1841

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11597285?tool=bestpractice.com

There is insufficient evidence to determine whether it can be used safely in children.[58]Tavender E, Eapen N, Wang J, et al. Triage tools for detecting cervical spine injury in paediatric trauma patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024 Mar 22;3(3):CD011686.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011686.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38517085?tool=bestpractice.com

The Canadian C-spine rule comprises 3 sets of questions:

Is there any high-risk factor present that mandates radiography (i.e., age ≥65 years, dangerous mechanism, or paresthesias in extremities)?

Is there any low-risk factor present that allows safe assessment of range of motion (i.e., simple rear-end motor vehicle collision, sitting position in emergency department, ambulatory at any time since injury, delayed onset of neck pain, or absence of midline C-spine tenderness?

Is the patient able to actively rotate neck 45° to the left and right?

Imaging is indicated for any trauma patient identified by the Canadian C-spine rule as having:

a high-risk factor for cervical spine injury or

a low-risk factor for cervical spine injury, and they are unable to actively rotate their neck 45° to both left and right.

NEXUS criteria

Intended to help physicians identify which patients need cervical spine radiography following blunt trauma. Five criteria must be met in order for the patient to be classified as having a low risk of cervical spine injury, as follows:[59]Hoffman JR, Mower WR, Wolfson AB, et al. Validity of a set of clinical criteria to rule out injury to the cervical spine in patients with blunt trauma. National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jul 13;343(2):94-9.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJM200007133430203?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10891516?tool=bestpractice.com

No tenderness at the posterior midline of the cervical spine

No focal neurological deficit

Normal level of alertness

No evidence of intoxication

No clinically apparent, painful injury that might distract the patient from the pain of a cervical spine injury.

Evidence from some retrospective studies suggests there is a risk of false-negative results when using the NEXUS criteria alone in children.[58]Tavender E, Eapen N, Wang J, et al. Triage tools for detecting cervical spine injury in paediatric trauma patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024 Mar 22;3(3):CD011686.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011686.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38517085?tool=bestpractice.com

Further evidence is needed to determine whether it is an appropriate tool for the clearance of cervical spine following blunt trauma in pediatric trauma care.

Nontraumatic neck pain: clinical features of concern

The presentation of a patient with neck pain with no history of trauma can vary considerably, and the pain may be acute or chronic in nature. It is important to be aware of features that increase the risk of a more ominous cause.

Fever in a patient with new neck pain

In these patients, neck pain should be assumed to be secondary to an infection until proven otherwise.

Patients with an infectious cause may be hypotensive or tachycardic.

There may be a history of recent infection (especially skin or urinary tract), immune compromise, or intervention associated with infection, such as surgery, trauma, or intravenous (IV) drug use.

Cervical osteomyelitis and cervical epidural abscesses arise from hematogenous spread in most cases. About one third of cases of cervical epidural abscesses arise from contiguous spread from the skin.[24]Darouiche RO. Spinal epidural abscess. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 9;355(19):2012-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17093252?tool=bestpractice.com

The most common symptoms are pain, fever, and neurologic compromise.

Patients with meningitis may also have nuchal rigidity.

A history of, or symptoms suggestive of, cancer

In a patient with a history of cancer, the etiology of neck pain should be assumed to be from cancer until this is ruled out.

Cancers that may cause neck pain include pharyngeal cancer and those that are more likely to metastasize to the cervical spine, such as thyroid cancer.

Tumor-related neck pain is more commonly unrelenting pain that is often worse at night (this symptom is unusual in most other causes of neck pain).[23]Abdu WA, Provencher M. Primary bone and metastatic tumors of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998 Dec 15;23(24):2767-77.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9879102?tool=bestpractice.com

Other signs and symptoms of cancer include unexplained weight loss, fatigue, or an unusual lump or swelling.

Neurologic symptoms or deficits

Investigations should be expedited in patients presenting with pain radiating from the neck into the arm, numbness in the arms, weakness, loss of coordination, changes in gait, and change in bowel or bladder function. All are indicative of possible neurologic compromise.

Symptoms suggestive of stroke or transient ischemic attack could indicate cervical artery dissection.

Ipsilateral headache, eye pain, Horner syndrome, cranial nerve palsies, hemiplegia, hemisensory loss, neglect, and homonymous hemianopia can occur in carotid artery dissection, while vertigo, ataxia, dysarthria, and headache can occur in cases of vertebral artery dissection.[32]Gottesman RF, Sharma P, Robinson KA, et al. Clinical characteristics of symptomatic vertebral artery dissection: a systematic review. Neurologist. 2012 Sep;18(5):245-54.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3898434

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22931728?tool=bestpractice.com

Nontraumatic neck pain: further history

Occupational history should be considered. Neck pain is prevalent among workers in the construction industry and in the agricultural sector.[60]Umer W, Antwi-Afari MF, Li H, et al. The prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms in the construction industry: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2018 Feb;91(2):125-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29090335?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Jackson JA, Liv P, Sayed-Noor AS, et al. Risk factors for surgically treated cervical spondylosis in male construction workers: a 20-year prospective study. Spine J. 2023 Jan;23(1):136-45.

https://www.thespinejournalonline.com/article/S1529-9430(22)00872-5/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36028215?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Czępińska A, Zawadka M, Wójcik-Załuska A, et al. Association between pain intensity, neck disability index, and working conditions among women employed in horticulture. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2023 Sep 28;30(3):531-5.

https://www.aaem.pl/Association-between-pain-intensity-neck-disability-index-and-working-conditions-among,162028,0,2.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37772530?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Fethke NB, Merlino LA, Gerr F, et al. Musculoskeletal pain among Midwest farmers and associations with agricultural activities. Am J Ind Med. 2015 Mar;58(3):319-30.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25345841?tool=bestpractice.com

[64]Scutter S, Türker KS, Hall R. Headaches and neck pain in farmers. Aust J Rural Health. 1997 Feb;5(1):2-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9437926?tool=bestpractice.com

Office workers and computer users are also at risk for neck pain.[65]Ye S, Jing Q, Wei C, et al. Risk factors of non-specific neck pain and low back pain in computer-using office workers in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017 Apr 11;7(4):e014914.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/7/4/e014914

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28404613?tool=bestpractice.com

[66]Côté P, van der Velde G, Cassidy JD, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in workers: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 Feb 15;33(4 suppl):S60-74.

https://journals.lww.com/spinejournal/fulltext/2008/02151/the_burden_and_determinants_of_neck_pain_in.11.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18204402?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]Mazaheri-Tehrani S, Arefian M, Abhari AP, et al. Sedentary behavior and neck pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2023 Oct;175:107711.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37775083?tool=bestpractice.com

A history of mental stress, perceived inadequacy, and previous injury has been found to be associated with neck pain. Psychological and psychosocial factors, such as anxiety, catastrophizing, hypervigilance, and limited health literacy, may be important in predicting those who will go on to develop chronic neck pain.[9]Kazeminasab S, Nejadghaderi SA, Amiri P, et al. Neck pain: global epidemiology, trends and risk factors. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022 Jan 3;23(1):26.

https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-021-04957-4

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34980079?tool=bestpractice.com

[68]Verwoerd M, Wittink H, Maissan F, et al. Consensus of potential modifiable prognostic factors for persistent pain after a first episode of nonspecific idiopathic, non-traumatic neck pain: results of nominal group and Delphi technique approach. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020 Oct 7;21(1):656.

https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-020-03682-8

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33028268?tool=bestpractice.com

These factors may also lead to decreased compliance with exercise secondary to concern over injury or worsening the injury.[69]van der Donk J, Schouten JS, Passchier J, et al. The associations of neck pain with radiological abnormalities of the cervical spine and personality traits in a general population. J Rheumatol. 1991 Dec;18(12):1884-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1795327?tool=bestpractice.com

[70]Makela M, Heiliovaara M, Sievers K, et al. Prevalence, determinants, and consequences of chronic neck pain in Finland. Am J Epidemiol. 1991 Dec 1;134(11):1356-67.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1755449?tool=bestpractice.com

A previous history of injury, such as whiplash injury, may predispose to cervical facet syndrome.[71]Schofferman J, Bogduk N, Slosar P. Chronic whiplash and whiplash-associated disorders: an evidence-based approach. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007 Oct;15(10):596-606.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17916783?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with neck pain secondary to rheumatoid arthritis have often had the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis for several years by the time cervical spine involvement presents.[72]van Eijk IC, Nielen MM, van Soesbergen RM, et al. Cervical spine involvement is rare in early arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Jul;65(7):973-4.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1798217/?tool=pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16769788?tool=bestpractice.com

Neck pain typically radiates upward to the head.

Nontraumatic neck pain: physical exam

Neck exam

Includes assessment of outward appearance, palpation for tenderness, and assessment of range of motion (ROM).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Patient with severe left torticollis (note hypertrophy of right sternocleidomastoid muscle)From the personal collection of David B. Sommer, MD, MPH [Citation ends].

In general, abnormal appearance, abnormal ROM, and a tender cervical spine are nonspecific and indicate only that there is cervical spine disease, not a specific cause.

Apart from other systemic signs, patients with meningitis may have nuchal rigidity.[26]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Meningitis (bacterial) and meningococcal disease: recognition, diagnosis and management. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng240

[35]Durand ML, Calderwood SB, Weber DJ, et al. Acute bacterial meningitis in adults: a review of 493 episodes. N Engl J Med. 1993 Jan 7;328(1):21-8.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199301073280104#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8416268?tool=bestpractice.com

This is demonstrated by the inability of the patient to touch his/her chin to the chest with passive or active flexion of the neck. Kernig sign (painful/resisted extension of leg bent at hip and knee) and Brudzinski sign (reflective flexion of the knees when patient is on his/her back and the neck is bent forward) are tests used to demonstrate nuchal rigidity. The sensitivity and negative predictive value of Kernig and Brudzinski sign is low in the diagnosis of meningitis.[27]van de Beek D, Cabellos C, Dzupova O, et al. ESCMID guideline: diagnosis and treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016 May;22 Suppl 3:S37-62.

https://www.clinicalmicrobiologyandinfection.com/article/S1198-743X(16)00020-3/fulltext

Examination of the upper extremities

Neurologic exam

Includes careful evaluation for evidence of any:

decrease in sensation or strength, or abnormal reflexes, in the upper extremities

increased tone or spasticity, and abnormal reflexes, in the lower extremities.

Abnormal reflex responses include:

hyperreflexia or positive Babinski sign (hallux dorsiflexes with other toes fanning out)

positive Hoffman sign (involuntary flexion and adduction of the thumb and flexion of the index finger when the nail of the middle finger is flicked downwards), or

positive clonus (a rhythmic, oscillating, stretch reflex in response to rapid dorsiflexion of the ankle).

The hallmark clinical manifestations of cervical radiculopathies are pain, sensory loss, and motor weakness in the distribution of the affected nerve root.[73]Polston DW. Cervical radiculopathy. Neurol Clin. 2007 May;25(2):373-85.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17445734?tool=bestpractice.com

The most commonly affected nerve roots are C7 (50% to 70%), C6 (>20%), C8 (10%), and C5 (2% to 10%).[73]Polston DW. Cervical radiculopathy. Neurol Clin. 2007 May;25(2):373-85.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17445734?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis may present with uncomplicated neck pain, which may progress to myelopathy due to cervical spine subluxation. Painless sensory loss in the hands and feet may be present. With cervical subluxation, there may be extremity weakness or spasticity. Deep tendon reflexes are also increased.

Assess for hemiplegia, hemisensory loss, cranial nerve palsies, visual field defects, and cerebellar dysfunction if cervical artery dissection is suspected.

Skin inspection

Central nervous system (CNS) infections (e.g., due to Neisseria meningitidis) can cause skin manifestations such as petechiae and palpable purpura.

A papulovesicular rash in a dermatomal distribution indicates herpes zoster infection.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Zostiform vesicular eruption within the D8 dermatome on the leftBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2006.114116. Copyright © 2011 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].

Provocative tests

Spurling, shoulder abduction, and upper limb tension tests may be performed to test for cervical radiculopathy.[74]Bono CM, Ghiselli G, Gilbert TJ, et al; North American Spine Society. An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cervical radiculopathy from degenerative disorders. Spine J. 2011 Jan;11(1):64-72.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21168100?tool=bestpractice.com

These tests should not be performed in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, infection, or possible neck injury.

To perform the Spurling maneuver, while sitting, the patient's neck is slightly flexed to the side of pain and downward pressure is applied to the top of the head. The test is positive if pain radiates into the limb on the side that the head is rotated to. A positive test is highly suggestive of cervical radiculopathy.[75]Tong HC, Haig AJ, Yamakawa K. The Spurling test and cervical radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002 Jan 15;27(2):156-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11805661?tool=bestpractice.com

The test has low sensitivity (30%) using electrodiagnostic studies as reference, but high specificity (93%).[75]Tong HC, Haig AJ, Yamakawa K. The Spurling test and cervical radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002 Jan 15;27(2):156-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11805661?tool=bestpractice.com

Nontraumatic neck pain: laboratory investigations

There is no evidence that routine laboratory testing is helpful in the evaluation of neck pain. However, the following tests are indicated if there is suspicion of serious etiology, such as infection, malignancy, or inflammatory arthritis:

If there is a concern for meningitis or encephalitis

Lumbar puncture should be performed, and the following cerebrospinal fluid investigations requested:[26]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Meningitis (bacterial) and meningococcal disease: recognition, diagnosis and management. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng240

Fungal and viral cultures can be ordered if the patient is immunocompromised and there is concern for these infections. Acid-fast bacilli stain and smear is ordered if there is any history of tuberculosis exposure or if the patient is purified protein derivative positive.[76]Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention clinical practice guidelines: diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Jan 15;64(2):e1-33.

https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/64/2/e1/2629583

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27932390?tool=bestpractice.com

If there is concern for cervical spine infection

Blood cultures should be drawn upon presentation if a patient is febrile and is suspected of having a cervical spine infection.

If vertebral osteomyelitis is suspected, and a microbiologic diagnosis for a known associated organism has not been established by blood cultures or serologic tests, a biopsy of the vertebra(e) thought to be infected should be sent for Gram stain and cultures with sensitivity.[77]Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, et al. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Sep 15;61(6):e26-46.

https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/61/6/e26/452579

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26229122?tool=bestpractice.com

Nontraumatic neck pain: imaging

Cervical spine x-ray

Indicated in patients ages >50 years with new neck pain, or constitutional symptoms such as signs of infection. In cases of infection such as diskitis, endplate destruction at the level of infection may be seen.[1]Guzman J, Haldeman, S, Carroll LJ, et al. Clinical practice implications of the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders: from concepts and findings to recommendations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 Feb 15;33(4 suppl):S199-213.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18204393?tool=bestpractice.com

However, a negative cervical spine x-ray in a patient with fever is not sensitive enough to rule out infection; an MRI should be considered in those patients.[37]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging, Ortiz AO, Levitt A, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria: suspected spine infection. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Nov;18(11S):S488-501.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00724-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34794603?tool=bestpractice.com

The recommended imaging of the cervical spine is an x-ray with anterior-posterior, lateral, and open mouth views. Flexion/extension radiographs have limited value in degenerative disease.[78]White AP, Biswas D, Smart LR, et al. Utility of flexion-extension radiographs in evaluating the degenerative cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007 Apr 20;32(9):975-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17450072?tool=bestpractice.com

Cervical spondylosis (osteoarthritis of the spine, which includes the spontaneous degeneration of either disc or facet joints) is an almost universal finding with increasing age.[15]Theodore N. Degenerative cervical spondylosis. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 9;383(2):159-68. Only a subset of patients present with axial neck pain; many patients are asymptomatic.[16]Binder AI. Cervical spondylosis and neck pain. BMJ. 2007 Mar 10;334(7592):527-31.[17]Kelly JC, Groarke PJ, Butler JS, et al. The natural history and clinical syndromes of degenerative cervical spondylosis. Adv Orthop. 2012;2012:393642.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2012/393642

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22162812?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal lateral cervical spine x-rayWith permission of the University of Colorado Department of Radiology [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: C3-4 diskitis with endplate destructionWith permission of the University of Colorado Department of Radiology [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral facet dislocationWith permission of the University of Colorado Department of Radiology [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral facet dislocationWith permission of the University of Colorado Department of Radiology [Citation ends].

Cranial CT imaging

Indicated in patients with suspected bacterial meningitis when it is associated with one or more of the following: immunocompromised state, history of CNS disease, new-onset seizure, papilledema, abnormal level of consciousness, or focal neurologic deficit.[27]van de Beek D, Cabellos C, Dzupova O, et al. ESCMID guideline: diagnosis and treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016 May;22 Suppl 3:S37-62.

https://www.clinicalmicrobiologyandinfection.com/article/S1198-743X(16)00020-3/fulltext

[36]Hasbun R, Abrahams J, Jekel J, et al. Computed tomography of the head before lumbar puncture in adults with suspected meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2001 Dec 13;345(24):1727-33.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa010399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11742046?tool=bestpractice.com

Cervical spine MRI

Definitive test to evaluate patients for cervical radiculopathy or cervical myelopathy.[42]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: cervical pain or cervical radiculopathy. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69426/Narrative

[79]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: myelopathy. 2020 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69484/Narrative

Should be ordered if the patient with neck pain has neurologic symptoms and signs of cord compression (cervical myelopathy), progressive neurologic dysfunction (especially weakness) and lack of response to conservative therapy.[40]Carette S, Fehlings MG. Clinical practice. Cervical radiculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jul 28;353(4):392-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16049211?tool=bestpractice.com

MRI is not indicated as first-line imaging for patients with chronic, uncomplicated neck pain.[42]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: cervical pain or cervical radiculopathy. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69426/Narrative

MRI is the imaging study of choice for patients with suspected local infection.[37]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging, Ortiz AO, Levitt A, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria: suspected spine infection. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Nov;18(11S):S488-501.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00724-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34794603?tool=bestpractice.com

It is the recommended exam when there is evidence of bone or disk margin destruction. If an epidural abscess is suspected, MRI should be performed without and with IV contrast.[37]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging, Ortiz AO, Levitt A, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria: suspected spine infection. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Nov;18(11S):S488-501.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00724-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34794603?tool=bestpractice.com

The use of an IV contrast agent not only increases lesion conspicuity, but also helps to define the extent of the infection process.[37]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging, Ortiz AO, Levitt A, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria: suspected spine infection. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Nov;18(11S):S488-501.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00724-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34794603?tool=bestpractice.com

[80]Diehn FE. Imaging of spine infection. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012 Jul;50(4):777-98.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.rcl.2012.04.001

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22643395?tool=bestpractice.com

Cervical spine MRI should be used to evaluate neck pain in patients with a history of cancer.[42]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: cervical pain or cervical radiculopathy. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69426/Narrative

Cervical MRI should document encroachment of the cervical root(s) suspected by history and physical exam.

Anatomic abnormalities such as disk protrusion (herniation/bulge) have been reported in 57% of patients (ages >64 years) with asymptomatic degenerative disk disease.[81]Teresi LM, Lufkin RB, Reicher MA, et al. Asymptomatic degenerative disk disease and spondylosis of the cervical spine: MR imaging. Radiology. 1987 Jul;164(1):83-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3588931?tool=bestpractice.com

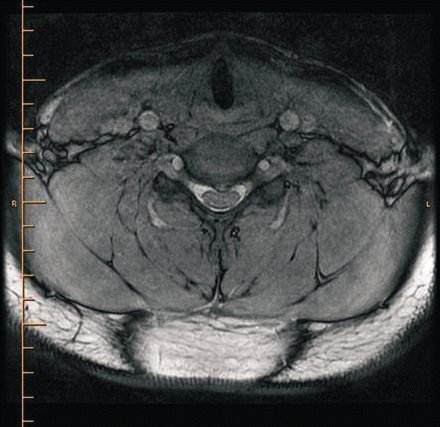

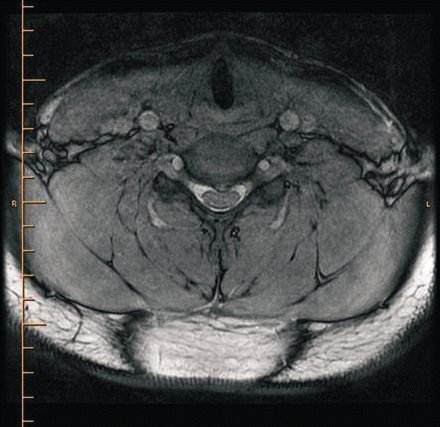

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI cervical spine. Axial three-dimensional cosmic at C5/C6 with anterior indentation of the thecal sacBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0573. Copyright © 2011 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI cervical spine. Sagittal T1, SE with a central disc at C5/C6 indenting the thecal sacBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0573. Copyright © 2011 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI cervical spine. Sagittal T1, SE with a central disc at C5/C6 indenting the thecal sacBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0573. Copyright © 2011 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].

Cervical spine CT scan and CT myelography

CT imaging may be indicated if MRI cannot be performed.[42]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: cervical pain or cervical radiculopathy. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69426/Narrative

CT myelography is used to visualize neurologic encroachment, as with MRI. It requires invasive placement of radiologic contrast into the epidural space and the use of radiation (and is therefore only recommended when cervical MRI is contraindicated).

Bone scan

Patients with new neck pain and a history of cancer, no matter how remote, should be evaluated for recurrence of their cancer with a bone scan to look for metastatic disease.[82]Canale ST, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell's operative orthopaedics. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

Cervical facet injection and arthrography

Evidence to support use of cervical facet/medial branch nerve blocks to identify the origin of a patient’s pain is inconsistent.[83]Hurley RW, Adams MCB, Barad M, et al. Consensus practice guidelines on interventions for cervical spine (facet) joint pain from a multispecialty international working group. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022 Jan;47(1):3-59.

https://rapm.bmj.com/content/47/1/3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34764220?tool=bestpractice.com

Image-guided medial branch nerve blocks may, however, be the most efficacious way of isolating a specific facet joint as the origin of pain.

When selecting targets for blocks, levels should be determined based on clinical presentation (tenderness on palpation, preferably performed under fluoroscopy, and pain referral patterns).[83]Hurley RW, Adams MCB, Barad M, et al. Consensus practice guidelines on interventions for cervical spine (facet) joint pain from a multispecialty international working group. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022 Jan;47(1):3-59.

https://rapm.bmj.com/content/47/1/3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34764220?tool=bestpractice.com

History and physical exam cannot reliably identify painful atlantooccipital and atlantoaxial joints, but can guide injection decisions.[83]Hurley RW, Adams MCB, Barad M, et al. Consensus practice guidelines on interventions for cervical spine (facet) joint pain from a multispecialty international working group. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022 Jan;47(1):3-59.

https://rapm.bmj.com/content/47/1/3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34764220?tool=bestpractice.com

Use of a single diagnostic block is recommended.[83]Hurley RW, Adams MCB, Barad M, et al. Consensus practice guidelines on interventions for cervical spine (facet) joint pain from a multispecialty international working group. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022 Jan;47(1):3-59.

https://rapm.bmj.com/content/47/1/3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34764220?tool=bestpractice.com

Dual blocks increase false-negative diagnoses (but can reduce the rate of false-positive diagnoses and enhance radiofrequency treatment success rates).[83]Hurley RW, Adams MCB, Barad M, et al. Consensus practice guidelines on interventions for cervical spine (facet) joint pain from a multispecialty international working group. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022 Jan;47(1):3-59.

https://rapm.bmj.com/content/47/1/3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34764220?tool=bestpractice.com

[84]Cohen SP, Huang JH, Brummett C. Facet joint pain-advances in patient selection and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013 Feb;9(2):101-16.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23165358?tool=bestpractice.com

Cervical diskography

CT angiography (CTA) and MR angiography (MRA)

Can identify cervical artery dissections.[29]Yaghi S, Engelter S, Del Brutto VJ, et al. Treatment and outcomes of cervical artery dissection in adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2024 Mar;55(3):e91-106.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000457

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38299330?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Hanning U, Sporns PB, Schmiedel M, et al. CT versus MR techniques in the detection of cervical artery dissection. J Neuroimaging. 2017 Nov;27(6):607-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28574627?tool=bestpractice.com

The sensitivity and specificity of CTA is similar to digital subtraction angiography (the historical gold standard for diagnosis of cervical artery dissection).[29]Yaghi S, Engelter S, Del Brutto VJ, et al. Treatment and outcomes of cervical artery dissection in adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2024 Mar;55(3):e91-106.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000457

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38299330?tool=bestpractice.com

CTA involves the administration of IV contrast. CTA is better than MRA in identifying pseudoaneurysms, intimal flaps, and high-grade stenosis. MRA may perform better in identifying small intramural hematomas.[29]Yaghi S, Engelter S, Del Brutto VJ, et al. Treatment and outcomes of cervical artery dissection in adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2024 Mar;55(3):e91-106.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000457

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38299330?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Hakimi R, Sivakumar S. Imaging of carotid dissection. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019 Jan 19;23(1):2.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30661121?tool=bestpractice.com

American Heart Association guidelines advise that either CTA or MRA can be used to evaluate patients with suspected extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease.[29]Yaghi S, Engelter S, Del Brutto VJ, et al. Treatment and outcomes of cervical artery dissection in adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2024 Mar;55(3):e91-106.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000457

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38299330?tool=bestpractice.com

[86]Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013 Jan 1;81(1):E76-123.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ccd.22983

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23281092?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral facet dislocationWith permission of the University of Colorado Department of Radiology [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral facet dislocationWith permission of the University of Colorado Department of Radiology [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI cervical spine. Sagittal T1, SE with a central disc at C5/C6 indenting the thecal sacBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0573. Copyright © 2011 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI cervical spine. Sagittal T1, SE with a central disc at C5/C6 indenting the thecal sacBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2008.0573. Copyright © 2011 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].