Approach

Primary and secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) usually present with nephrotic syndrome, but can also be detected at an earlier stage if proteinuria is noted on routine urinalysis.[12][23] There are no specific clinical features; other causes of nephrotic syndrome should be considered and excluded. Patients should be referred to a nephrologist as a renal biopsy is necessary to establish the definitive diagnosis. Further investigations are required to exclude secondary causes of FSGS before the disease can be classified as primary FSGS.

History

Most patients present with symptoms of edema and foamy urine. Edema usually starts in the legs and then spreads to involve the whole body. As primary FSGS produces more severe podocyte injury than secondary FSGS, it is more likely to present with nephrotic syndrome. Secondary FSGS is more likely to present with asymptomatic subnephrotic proteinuria that is incidentally detected.

The aim of the history is to seek clues about the underlying etiology. Black people have a 4- to 7-fold greater risk than white or Asian people of developing FSGS-induced end-stage renal failure.[8][9] Males have a 1.5- to 2-fold greater risk than females.[8] Key features of the history include:[4]

Age of the patient: FSGS occurs predominantly in adults. Nephrotic syndrome in children is caused by minimal change disease in almost all cases.[23]

History of heroin use, which is a known cause.

Medications: interferon-alfa, lithium, sirolimus, and pamidronate are known causes.

Medical history: causes of secondary FSGS to be sought in the history include HIV and other relevant chronic infections, previous nephrectomy (or, rarely, renal agenesis), obesity, and reflux nephropathy. If the patient has diabetes mellitus, diabetic nephropathy is more likely than FSGS.

Family history: a positive family history may identify the rare familial cases of FSGS.

Physical exam

Patients usually have mild edema of the legs or severe edema affecting the whole body (anasarca). Facial edema is more commonly seen in nephrotic syndrome than in heart failure or liver disease. Patients may develop white banding on the nails due to hypoalbuminemia (Muehrcke lines) and cholesterol deposits in the skin (xanthomata or xanthelasmas) due to hypercholesterolemia. Hypertension is common. These features suggest the diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome but are not useful for elucidating the cause.

Examination may reveal features of the underlying cause, prompting consideration of secondary FSGS.

Obesity can be confirmed by determination of the body mass index (BMI) and is defined as BMI in the 95th percentile or greater.

Patients with HIV may have rashes or postinfective scars (especially shingles), oral lesions (ulcers, angular cheilitis, thrush, oral hairy leukoplakia, or oral Kaposi sarcoma), severe weight loss, wasting syndrome, or generalized lymphadenopathy.

A nephrectomy scar may be noted on an abdominal exam.

It is also important to be alert for signs suggesting medical conditions other than FSGS. These include diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), amyloidosis, and multiple myeloma.

A photosensitive rash may indicate SLE.

Easy bruising and neuropathy suggest amyloidosis.

Diabetic retinopathy in a patient with diabetes mellitus should prompt consideration of diabetic nephropathy.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Facial edema in a child with nephrotic syndromeFrom the collection of Dr M. Dixit, Medical Director, Florida Children's Kidney Centre; Dr R. Mathias, Chief, Pediatric Nephrology, Nemours Children's Clinic, Orlando, FL [Citation ends].

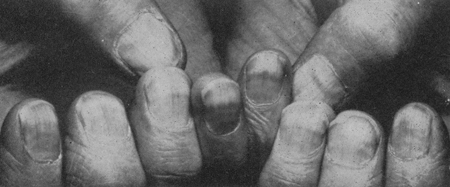

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Muehrcke lines in a patient with hypoalbuminemia due to nephrotic syndromeFrom Muehrcke RC. The finger-nails in chronic hypoalbuminaemia: a new physical sign. Br Med J. 1956 Jun 9;1(4979):1327-8 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Muehrcke lines in a patient with hypoalbuminemia due to nephrotic syndromeFrom Muehrcke RC. The finger-nails in chronic hypoalbuminaemia: a new physical sign. Br Med J. 1956 Jun 9;1(4979):1327-8 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Xanthomata in a patient with severe hyperlipidemiaFrom Watkins PJ. Cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and lipids. BMJ. 2003 Apr 19;326(7394):874-6 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Xanthomata in a patient with severe hyperlipidemiaFrom Watkins PJ. Cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and lipids. BMJ. 2003 Apr 19;326(7394):874-6 [Citation ends].

Laboratory investigations

The main aim of laboratory investigations is to assess the severity of the disease and identify causes of secondary FSGS.

Renal function should be assessed with serum BUN and creatinine, including estimation of the GFR.

Urinalysis and urine microscopy typically reveal oval fat bodies and fatty casts. Microscopic hematuria may be present but red cell casts are absent. The severity of proteinuria must be measured, either by urine protein-to-creatinine ratio or by 24-hour urine collection. Proteinuria ranges from <1 g/24 hours in asymptomatic patients to >3 g/24 hours in patients with nephrotic syndrome.

Serum albumin and cholesterol measurements are required to assess the severity of hypoalbuminemia and hypercholesterolemia.

Further laboratory investigations are used to identify known causes of secondary FSGS and exclude non-FSGS causes of nephrotic syndrome. Routine screening to detect genetic causes of primary FSGS is not required and should be considered only in rare cases where the family history strongly suggests familial FSGS. Secondary causes must be excluded before primary FSGS is diagnosed.

DNA polymerase chain reaction assays are useful to identify chronic parvovirus and cytomegalovirus infections. If the patient is HIV-positive, or is strongly suspected of being HIV-positive after assessment of risk factors and/or clinical features, HIV antibody testing, a CD4 count, and viral load studies are required. Hepatitis B and C serology to exclude chronic infection is also useful.

The following tests are useful to exclude non-FSGS causes of nephrotic syndrome:

Antinuclear antibody or anti-double-stranded DNA titers if clinical features suggest SLE.

Serum and urine protein electrophoresis if amyloidosis is suspected.

Imaging

Bilateral renal ultrasound is useful to assess the size of the kidneys but is not diagnostic. In the early stages, ultrasound exam reveals normal or large kidneys with increased echogenicity, suggesting diffuse intrinsic renal disease. In patients with advanced renal failure, kidneys are small and shrunken, indicating severe glomerular scarring and interstitial fibrosis.

Renal biopsy

The decision to perform a biopsy should be made by a nephrologist. A definitive diagnosis of FSGS can only be made based on findings from renal biopsy.

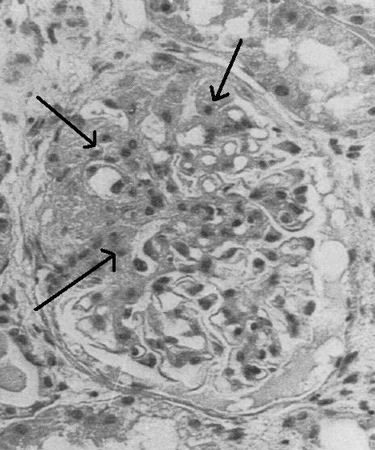

Light microscopy of the biopsy specimen reveals the characteristic pattern of focal and segmental sclerosis of the glomeruli that gives the condition its name. The disease is categorized morphologically as perihilar variant, cellular variant, collapsing variant, tip variant, or not otherwise specified.[2][3] Some variants are associated with specific causes, such as HIV which causes the collapsing variant. The morphologic types are not used to guide treatment but provide useful prognostic information.

Immunofluorescence microscopy is unremarkable in FSGS. Immune deposits are usually absent except for nonspecific binding of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and C3 deposits in sclerotic lesions. Very weak mesangial deposition of IgM may also be observed.

Electron microscopy can be used to distinguish primary and secondary FSGS. In primary FSGS, foot process fusion is diffuse and occurs throughout the glomeruli. In secondary FSGS, foot process fusion is mostly limited to the sclerotic areas.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Light microscopy of renal biopsy showing typical lesions of focal segmental glomerulosclerosisAdapted from Nagi AH, Alexander F, Lannigan R. Light and electron microscopical studies of focal glomerular sclerosis. J Clin Pathol. 1971 Dec;24(9):846-50 [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer