Etiology

Rabies is caused by various negative-sense RNA viruses of the Lyssavirus genus, which belongs to the Rhabdoviridae family. The genus is composed of 17 recognized species: rabies virus, Lagos bat virus, Mokola virus, Duvenhage virus, Aravan virus, Irkut virus, Khujand virus, European bat lyssavirus types 1 and 2, West Caucasian bat virus, Australian bat lyssavirus type 1, Shimoni bat virus, Ikoma virus, Bokeloh bat lyssavirus, Gannoruwa lyssavirus, Bat lyssavirus, and Taiwan bat lyssavirus.[18][19][20]

Rabies is usually transmitted to humans following a bite from an infected animal including bats, foxes, raccoons, jackals, and mongooses. Dogs are the most common source globally, while bats are the major source in the US and the Americas. Nonbite exposures are also possible and include being scratched, being licked over an open wound or mucous membrane, or being exposed to infected brain tissue or CSF.

There are reported cases of rabies being transmitted by organ transplantation.[21][22][23][24]

Rabies has been reported in an anteater (tamandua) which was translocated from Virginia to Tennessee. All exposed people received postexposure vaccination and no human cases occurred. This case demonstrates the possibility of rabies translocation by human movement of captive mammals, including species in which rabies has not been previously reported.[25]

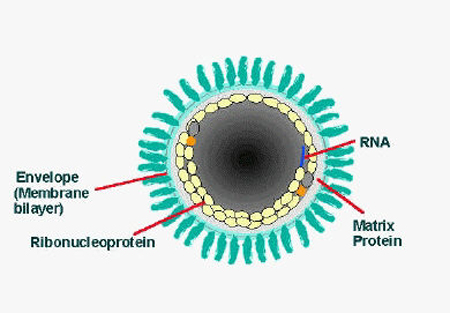

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Illustration of rabies virus in longitudinal sectionCDC [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Illustration of rabies virus in cross-section. Concentric layers: envelope membrane bilayer, M protein, and tightly coiled encased RNACDC [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Illustration of rabies virus in cross-section. Concentric layers: envelope membrane bilayer, M protein, and tightly coiled encased RNACDC [Citation ends].

Pathophysiology

The incubation period is variable. It is usually 2 weeks to 3 months but with a range from 5 days to 7 years (very rare). Shorter incubation periods are associated with severe bites and bites to the head and face.

The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at the motor end plate mediates virus entry to myocytes, where initial replication takes place.[26] The virus enters the nervous system through unmyelinated sensory and motor terminals and is transported by fast retrograde axonal transport, crossing new synapses roughly every 12 hours. Once the virus has entered the central nervous system, it is sequestered from the immune system and immunization will not be effective. In vitro studies have shown evidence of oxidative stress caused by mitochondrial dysfunction in neurons and other cells of the CNS.[27] Clinical symptoms begin once the virus infects the spinal cord and progress rapidly as the virus spreads through the CNS.[28] The rabies virus exits the CNS through motor, sensory, and autonomic nerves, and replicates locally in salivary and lacrimal glands in order to be transmitted to the next host.

Many aspects of rabies pathophysiology remain a mystery. It is unclear how rabies causes paralysis.[29] The pathophysiologic differences between the encephalitic and paralytic forms of rabies may involve differences in the host inflammatory response.[30] The cause of death in rabies is unknown because wild-type viruses are not cytopathic, apoptotic, or inflammatory.

Atypical, less severe forms of neurological illness are beginning to be reported, suggesting a continuum of rabies severity.[2][3][4][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: This transmission electron micrograph reveals the presence of Lagos bat virus virions and an intracytoplasmic inclusion body in this tissue sampleCDC; Dr Fred Murphy; Sylvia Whitfield [Citation ends].

Classification

Clinical classification

Encephalitic (furious) rabies

A febrile prodrome is followed by behavioral changes, including alternating agitation and normalcy, insomnia, and hallucinations. Paresthesias and paralysis may occur. Coma and death follow.

Paralytic rabies

A febrile prodrome is followed by rapid progression to flaccid paralysis. Behavioral changes occur late.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer