Approach

Initial evaluation of patients with suspected essential thrombocythemia (ET) includes a history and physical exam to assess for signs and symptoms of thrombosis, and possible causes of thrombocytosis.

Diagnosis of ET is based on the World Health Organization classification and requires assessment of clinical and laboratory (blood and bone marrow) features, and exclusion of secondary or reactive causes of thrombocytosis (see Diagnostic criteria).[2]

Once a diagnosis of ET is made, it is important to establish each patient's risk of developing thrombotic complications or bleeding. This will enable the most appropriate preventative and therapeutic management.

History

A complete history should be taken, including history of recent surgery, trauma, malignancy, infection, prior splenectomy, and presence of iron-deficiency anemia. These factors may cause reactive or secondary thrombocytosis and need to be excluded.

Risk factors for thrombotic or hemorrhagic complications

A history of certain risk factors will determine whether patients are at low or high risk of thrombotic or hemorrhagic complications. These risk factors include presence of thrombotic or hemorrhagic comorbidity, as well as cardiovascular risk factors, including history of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke, or familial thrombophilia.

In pregnant women, history of previous pregnancies, miscarriages, bleeding, and fetal loss is important to determine. Among pregnant women, ET is associated with increased risk for spontaneous abortion.[10]

Signs and symptoms

Approximately 40% to 50% of patients with ET are asymptomatic at diagnosis, and thrombocytosis is an incidental finding on routine blood testing.[3][4]

Symptomatic patients commonly present with vasomotor symptoms or complications from thrombosis or bleeding.[3][5]

Vasomotor symptoms may include headache, lightheadedness, chest pain, paresthesia, vertigo, dizziness, and erythromelalgia (characterized by burning pain and dusky congestion of the extremities). Syncope, seizures, and transient visual disturbances are uncommon vasomotor manifestations. Vasomotor symptoms are not specific to ET and, regardless of cause, a high platelet count could be associated with these symptoms.

Thrombotic events may include stroke, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), retinal artery or venous occlusions, coronary artery occlusion, pulmonary embolism, hepatic or portal vein thrombosis, deep vein thrombosis, digital ischemia, and priapism (a rare complication related to corpus cavernosum thrombosis).[6] Digital ischemia may initially manifest as Raynaud phenomenon with pallor and/or cyanosis of the digits, but may progress to ischemic necrosis of the terminal phalanges. Patients with TIA should undergo carotid ultrasound to rule out carotid artery stenosis.

Bleeding events are usually mild and manifest as epistaxis or easy bruising. The gastrointestinal tract is the most common site of major bleeding.[7] Increased risk of bleeding is associated with extreme thrombocytosis (platelet count >1 million/microliter) and use of aspirin in doses of >325 mg/day.[34]

Physical examination

There are no signs specific to ET, but the absence of conditions that may cause secondary or reactive thrombocytosis, together with presence of splenomegaly, may suggest the diagnosis. Splenomegaly is present in approximately 10% to 20% of ET patients at diagnosis, and is usually modest in degree.[8][9]

Patients should be examined for signs of anemia, infection, malignancy, or a surgical scar consistent with splenectomy to rule out secondary causes of thrombocytosis.

Livedo reticularis (a purplish mottled discoloration of the skin, usually on the legs, typically described as lacy or net-like in appearance) may occur in ET, but is also seen in several connective tissue diseases (e.g., lupus, antiphospholipid syndrome, Sneddon syndrome). This may help establish the diagnosis of reactive thrombocytosis.

Initial laboratory tests

Initial laboratory tests include a complete blood count (CBC) (with differential), peripheral blood smear, and serum iron studies. Laboratory findings can help to rule out possible causes of reactive or secondary thrombocytosis (e.g., inflammatory or infectious conditions, splenectomy, and iron deficiency).

CBC

Patients with ET will have a persistent and unexplained elevated platelet count. Thrombocytosis is the hallmark of ET.

Platelet count can range from 450,000/microliter to >1 million/microliter. The degree of thrombocytosis cannot be used to predict the likelihood of ET; the platelet count may be elevated to the same range in people with reactive thrombocytosis. If thrombocytosis is reported in the initial study, it should be confirmed by repeat testing and examination of the peripheral blood smear.[35]

White blood cell count is usually normal, but can be mildly elevated in ET. Patients with reactive thrombocytosis caused by inflammatory or infectious conditions may have an elevated white blood cell count.

Peripheral blood smear

In patients with ET, peripheral blood smear will show thrombocytosis with varying degrees of platelet anisocytosis (ranging from normal size platelets with normal granulation, to large platelets [thrombocytes] that are hypogranular). Immature precursor cells (e.g., myelocytes, metamyelocytes) may also be seen.

Red blood cells (RBCs) on peripheral blood smear are usually normochromic and normocytic in patients with ET. Hypochromic and microcytic RBCs may indicate iron deficiency (a cause of reactive thrombocytosis).

Patients who have undergone splenectomy or have reduced splenic function (hyposplenism) may have a secondary thrombocytosis. Peripheral blood smear in these patients will show nuclear fragments (Howell-Jolly bodies) in RBCs, along with target cells and misshapen RBCs.

Serum iron studies

A low serum ferritin level (e.g., <12 nanograms/mL [varies between guidelines]) is diagnostic of iron deficiency, with a specificity approaching 100%.

Subsequent testing

Tests for specific causes of thrombocytosis should be directed by the suspected diagnosis from clinical evaluation.

Serum CRP, ESR, and fibrinogen testing

Serum C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and fibrinogen are acute phase reactants and markers for underlying inflammation. They are usually normal in ET, and increased in most cases of reactive thrombocytosis.

Bone marrow exam

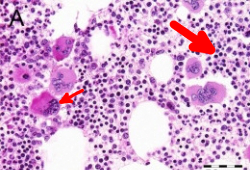

Indicated if there is evidence of thrombocytosis on CBC and peripheral blood smear without an identifiable cause. Bone marrow biopsy in patients with ET will show proliferation of the megakaryocyte lineage with increased numbers of enlarged, mature megakaryocytes with hyperlobulated nuclei. Furthermore, there will be no significant increase or left shift in neutrophil granulopoiesis or erythropoiesis, and no major increase in reticulin fibers. Minor (grade 1) increase in reticulin fibers may be seen, but is rare. A major increase in reticulin fibers would suggest prefibrotic/early primary myelofibrosis (prePMF). Distinguishing between ET and prePMF may be challenging.[36] It is critical to make this distinction on bone marrow biopsy as these two disorders have significantly different prognoses. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic bone marrow features of essential thrombocythemia in trephine biopsies stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Increase in cellularity (thick arrow) and increase in number of enlarged, mature megakaryocytes with hyperlobulated nuclei (thin arrow)Reproduced with permission from Michiels JJ, de Raeve H, Hebeda K, et al. Leuk Res. 2007 Aug;31(8):1031-8 [Citation ends].

Genetic mutation testing (JAK2 V617F, CALR, and MPL)

All patients with suspected ET should undergo molecular testing (on peripheral blood or alternatively bone marrow) for the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) V617F mutation initially. If negative, testing for calreticulin (CALR), and myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene (MPL) mutations should follow.[37] Alternatively, a next-generation sequencing panel comprising all three myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) driver mutations can be used.

Presence of a JAK2 V617F, CALR, or MPL mutation indicates an MPN, but these driver mutations are not specific for ET. JAK2 V617F, CALR, and MPL mutations are present in approximately 50% to 60%, 25% to 30%, and 3% to 11% of patients with ET, respectively.[18] Approximately 10% to 15% of patients with ET are negative for all three driver mutations (triple‐negative); therefore, absence of these mutations does not exclude the diagnosis.[18] JAK2 V617F, CALR, and MPL mutations may occur in other myeloproliferative neoplasms (polycythemia vera, primary myelofibrosis) and myeloid malignancies.

Driver mutation expression is often considered to be mutually exclusive in ET; however, there are reports of patients with coexisting JAK2 V617F and CALR, or JAK2 V617F and MPL, mutations.[19][20]

Treatment for ET may be individualized based on mutation status

JAK2 V617F mutation: associated with higher risk of thrombosis (particularly among homozygotes [>50% mutant allele burden] and those who are younger [ages <60 years]) and a lower risk of post-ET myelofibrosis.[26][27][28][29][30][38] Patients with JAK2 V617F mutation display higher leukocyte count and hemoglobin levels than those without the mutation.[28][31]

CALR mutation: associated with younger age, male sex, lower hemoglobin level, higher platelet count, lower leukocyte count, and lower risk of thrombosis, compared with JAK2 V617F-mutated ET.[38][39]

MPL mutation: inconsistently associated with older age, female sex, lower hemoglobin level, higher platelet count, and possible inferior myelofibrosis-free survival, compared with MPL wild-type ET.[38]

Cytogenetic and molecular testing: BCR::ABL1

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) should be carried out to detect BCR::ABL1 (Philadelphia chromosome).[37]

Absence of BCR::ABL1 helps rule out chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), a myeloproliferative neoplasm that can present initially with isolated thrombocytosis. It is important to rule out CML because prognosis and management of this condition is very different from that of ET.[40]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer