Approach

Characteristic history and examination findings are often insufficient for the diagnosis of angiodysplasias, and endoscopy is required for definitive diagnosis.

As gastrointestinal bleeding is a leading cause of hospitalization, prompt identification of the bleeding site is crucial to guide appropriate targeted therapy.

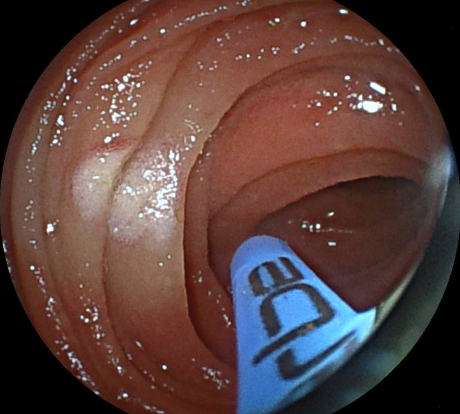

Small bowel capsule endoscopy should be the first-line modality to investigate recurrent anemia and chronic bleeding in the elective setting. In the context of brisk lower gastrointestinal bleeding, computed tomographic (CT) angiography would be the appropriate first test when there is hemodynamic compromise. Exams such as radionuclide scans, CT enterography, and transcatheter arteriography may be appropriate.[18][34]

Risk stratification tools such as the Oakland score can be used to identify patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding who can be managed on an outpatient basis or may be suitable for an early discharge.[35][36][37] The American College of Gastroenterology recommends that this tool should only be used as an adjunct to clinician judgement.[35]

History

The following factors have been associated with increased risk for, or higher frequency of, angiodysplasia: chronic renal failure/end-stage renal disease, von Willebrand disease, aortic stenosis, scleroderma, cardiovascular disease, and increasing age.

Patients are often ages >60 years and display chronic, painless, low-grade, intermittent bleeding, with either fresh rectal bleeding in lower gastrointestinal disease or melena in upper gastrointestinal disease. There may be long periods of time between bleeding episodes and symptoms of anemia, such as fatigue, weakness, pallor, and shortness of breath. In rare cases, patients may present with massive hemorrhage (hematochezia or hematemesis), and resulting postural hypotension and tachycardia.

Physical examination

A full physical assessment is recommended with evaluation of circulatory status including documentation of vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate). Rectal exam may demonstrate fresh red blood or melena.

Laboratory tests

On admission, a complete blood count is recommended to identify and quantify anemia (hemoglobin levels, microcytosis, and hypochromia). Blood chemistry is also completed to indicate any concomitant renal impairment. A high BUN may indicate upper gastrointestinal blood loss and, with a high BUN/Cr, dehydration.

Blood grouping and crossmatch are completed, if clinically indicated for a potential blood transfusion.

Endoscopy

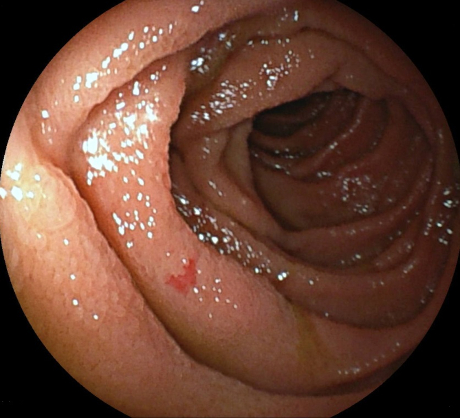

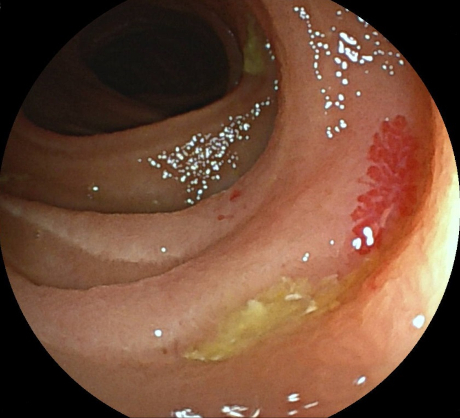

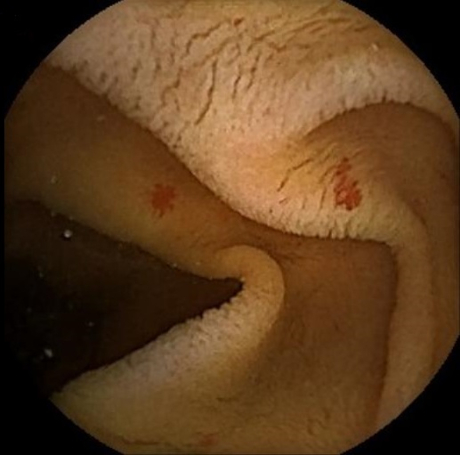

Imaging is often needed for diagnosis. Endoscopy, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy, is recommended initially to rule out an upper gastrointestinal bleed and to assess the lower gastrointestinal wall. Angiodysplasia is visualized as bright red lesions, 5 to 10 mm in diameter, with a branching surface network of fine, ectatic blood vessels arising from a central vessel. In hospitalized patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding, the American College of Gastroenterology and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommend a nonurgent inpatient colonoscopy, as rebleeding may be missed if an urgent colonoscopy is performed.[35][38]

Repeat testing may be necessary to identify some lesions, as poor bowel preparation or a transient decrease in mucosal blood flow due to sedative opioids can make identification difficult.[39] Injection of naloxone during the procedure may enhance visualization but must be balanced against the effect on patient comfort.[39] Second-look upper endoscopy may be required for patients with recurrent hematemesis or melena or for those who have had a previously inadequate exam.[8] Second-look colonoscopy may be rarely indicated in the setting of recurrent hematochezia or if a lower source of bleeding is suspected. A normal second-look exam warrants small bowel evaluation.[8]

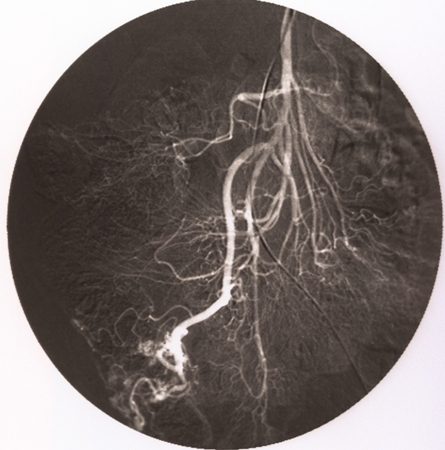

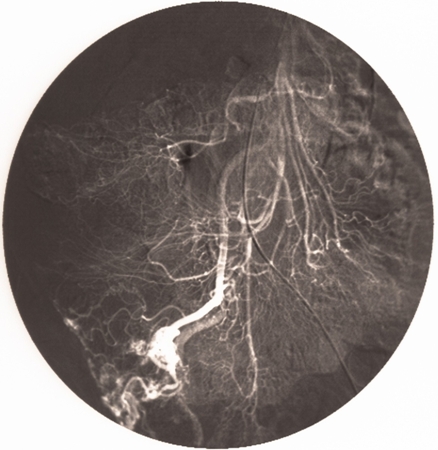

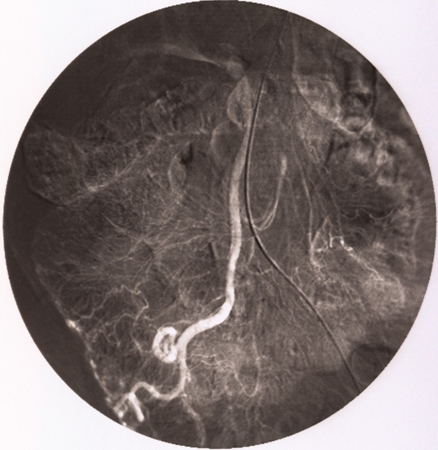

In patients with acutely bleeding lesions (equivalent to 3 units of blood loss per day) and non-diagnostic colonoscopy, CT angiography should be performed to assess the arterial anatomy and localize the bleeding point, followed by mesenteric angiography with a view to embolization.[40][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ileocolic artery on mesenteric angiogram. Vascular tufts and tangles from local mass of irregular vessels displayedImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ileocolic artery on mesenteric angiogramImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends].

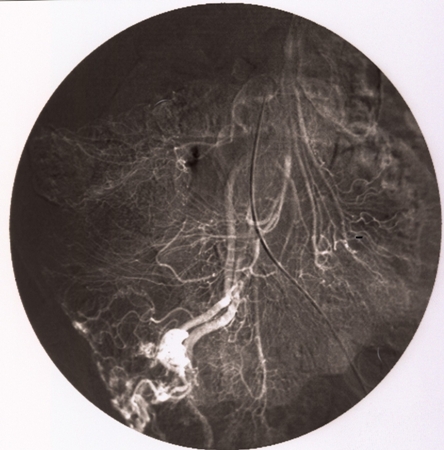

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ileocolic artery on mesenteric angiogramImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Early and intensely filling vein resulting from direct arteriovenous communicationImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends].

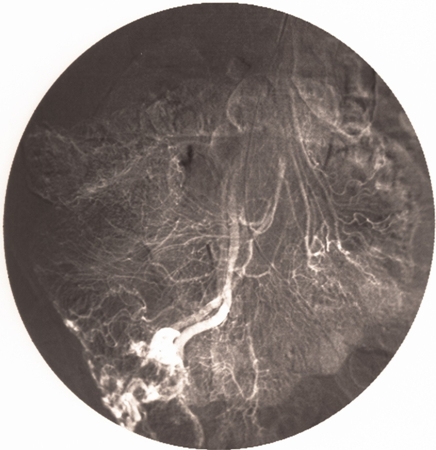

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Early and intensely filling vein resulting from direct arteriovenous communicationImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Persistent opacification beyond normal venous phaseImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Persistent opacification beyond normal venous phaseImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Persistent opacification beyond normal venous phaseImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Persistent opacification beyond normal venous phaseImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends].

Recommendations from the American Gastroenterological Association state that, when findings on standard examinations (EGD, colonoscopy, and mesenteric angiography) are negative, the small bowel may be assumed to be the source of blood loss.[40] Then, capsule endoscopy should be the next test in the evaluation of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding.[8][40][41] Capsule endoscopy allows wireless evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract.[9] It is typically performed in elective settings.

If the bleeding lesion is located to the proximal small bowel (and is not a mass), push enteroscopy may be used to reidentify and cauterize the lesion.[8] Push enteroscopy involves passing ("pushing") a long, fine endoscope (typically 2.6 m long, with a diameter of 11.2 mm) through the stomach, duodenum, and onward into the jejunum. If the bleeding lesion is located to the mid-distal jejunum or ileum, device-assisted enteroscopy, including single-balloon or double-balloon enteroscopy, may be performed, if available in the centre, to identify and treat the lesion.[42]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic (device-assisted enteroscopy) image of small bowel angiodysplasiaFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic (device-assisted enteroscopy) image of small bowel angiodysplasiaFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic (device-assisted enteroscopy) image of small bowel angiodysplasiaFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic (device-assisted enteroscopy) image of small bowel angiodysplasia after treatment with argon plasma coagulationFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic (device-assisted enteroscopy) image of small bowel angiodysplasia after treatment with argon plasma coagulationFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel angiodysplasia seen during small bowel capsule endoscopyFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel angiodysplasia seen during small bowel capsule endoscopyFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel angiodysplasia seen during small bowel capsule endoscopyFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel angiodysplasia seen during small bowel capsule endoscopyFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends].

Imaging

CT angiography is reported to improve the detection of gastrointestinal bleeding compared with colonoscopy and standard angiography.[43][44][45] In patients with overt lower gastrointestinal bleeding, CT imaging can determine the location, assess the intensity of the bleed, and identify the cause of bleeding.[18] CT angiography is rapid and noninvasive, but lacks therapeutic capability.

CT angiography should be performed as the first diagnostic study in emergency setting in patients with hemodynamic instability and can be considered as the initial diagnostic study in such patients when active bleeding is suspected.[18][35][38] Recommendations are against using CT angiography as a first-line test in hemodynamically stable patients in whom bleeding has subsided as the yield is low.[18] Radiation exposure and contrast allergy are potential concerns. In this setting, a capsule endoscopy may be more appropriate.

Radionuclide scans using technetium Tc-99m sulfur colloid or Tc-99m-labeled erythrocytes can be used to detect mild to moderate bleeding, although localization may be poor. Labeled erythrocytes have long intravascular half-life that enables continuous imaging of the gastrointestinal tract for several hours and, thus, are preferred for lower gastrointestinal bleeding imaging over Tc-99m sulfur colloid.[18]

The role of small bowel series, enteroclysis, cross-sectional imaging, and nuclear scans in the evaluation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding has declined substantially with the advent of capsule endoscopy because of their extremely low diagnostic yield.[40]

In the elective setting, when a patient presents with recurrent anemia and intermittent overt bleeding and EGD and colonoscopy are normal, capsule endoscopy should be the first-line investigation.[42] In patients with suspected small bowel bleeding and negative capsule endoscopy, multiphase CT enterography should be performed to locate the bleeding source, especially in those ages >40 years.[8][18]

In the acute setting, when a patient presents to hospital with suspected small bowel bleeding, the clinician needs to ensure that thorough investigation of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract has been previously performed before considering capsule endoscopy or CT angiography if there is evidence of hemodynamic compromise. These investigations can be performed together or sequentially depending on the urgency and hemodynamic status of the patient. In a patient with hemodynamic compromise and negative CT angiography findings, capsule endoscopy should still be carried out. The findings of capsule endoscopy would help direct if device-assisted enteroscopy to treat the lesion is needed.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer