Anaphylactic reaction

Anaphylactic reaction is typically a rapid onset of an urticarial eruption within minutes to hours of exposure, most often relating to a drug, food allergy, or insect bite or sting.

A maculopapular-appearing eruption may occur initially before the development of clinically typical urticaria.

Skin changes are often the first feature of allergic reactions and are present in >80% of patients with anaphylaxis.[81]Alvarez-Perea A, Tomás-Pérez M, Martínez-Lezcano P, et al. Anaphylaxis in adolescent/adult patients treated in the emergency department: differences between initial impressions and the definitive diagnosis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2015;25(4):288-94.

https://www.jiaci.org/summary/vol25-issue4-num1245

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26310044?tool=bestpractice.com

[82]Braganza SC, Acworth JP, Mckinnon DR, et al. Paediatric emergency department anaphylaxis: different patterns from adults. Arch Dis Child. 2006 Feb;91(2):159-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16308410?tool=bestpractice.com

Most patients who present with an acute onset maculopapular eruption in response to an allergen, do not progress to anaphylaxis.[1]Resuscitation Council UK. Emergency treatment of anaphylactic reactions: guidelines for healthcare providers. May 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.resus.org.uk/library/additional-guidance/guidance-anaphylaxis/emergency-treatment

[2]Lott C, Truhlář A, Alfonzo A, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation. 2021 Apr;161:152-219.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.011

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33773826?tool=bestpractice.com

Skin changes without life-threatening airway/breathing/circulation problems are not considered anaphylaxis.

Life-threatening manifestations most often involve the respiratory tract (edema, bronchospasm) and/or the circulatory system (vasodilatory shock).[83]Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabañas JG, et al. Part 3: Adult basic and advanced life support: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020 Oct 20;142(16_suppl_2):S366-468.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000916

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33081529?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients may have wheezing, tachypnea, chest hyperinflation, use of accessory muscles, or inspiratory stridor. Hypotension and tachycardia are often present. The patient may be flushed or pale.

Neurologic symptoms include agitation, confusion, dizziness, visual disturbances, tremor, syncope, and seizures. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain are common.

Epinephrine is the cornerstone of treatment for anaphylaxis.[83]Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabañas JG, et al. Part 3: Adult basic and advanced life support: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020 Oct 20;142(16_suppl_2):S366-468.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000916

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33081529?tool=bestpractice.com

[84]Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis-a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 Apr;145(4):1082-123.

https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(20)30105-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32001253?tool=bestpractice.com

Important historical considerations include:

Prior episodes

Intake of new medications (often antibiotics, particularly penicillins; more common with parenteral administration rather than oral ingestion)

Foods (often nuts or shellfish).

Emergency intervention for anaphylaxis:[1]Resuscitation Council UK. Emergency treatment of anaphylactic reactions: guidelines for healthcare providers. May 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.resus.org.uk/library/additional-guidance/guidance-anaphylaxis/emergency-treatment

[2]Lott C, Truhlář A, Alfonzo A, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation. 2021 Apr;161:152-219.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.011

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33773826?tool=bestpractice.com

Call for help

Remove trigger if possible (e.g., stop any infusion)

Lie patient flat

Give intramuscular epinephrine

Establish airway

Give high flow oxygen

Apply monitoring: pulse oximetry, ECG, blood pressure

Repeat intramuscular epinephrine after 5 minutes

Give intravenous fluid bolus.

Severe cutaneous drug eruptions

Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome are severe generalized eruptions that are most often drug-induced.[19]Dodiuk-Gad RP, Chung WH, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015 Dec;16(6):475-93.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26481651?tool=bestpractice.com

These eruptions typically start 4 to 28 days after drug exposure.[21]Duong TA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, et al. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs. Lancet. 2017 Oct 28;390(10106):1996-2011.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28476287?tool=bestpractice.com

The presence of fixed, sometimes painful skin lesions, dusky lesions with early erosion, and mucous membrane involvement (ocular, oral, and genital) are some defining characteristics of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN). Nikolksky sign, where the epidermal layer easily sloughs off when lateral pressure is applied, can occur. The chance of secondary infection is high.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is milder than toxic epidermal necrolysis, though the mortality rate of Stevens-Johnson syndrome is about 5% to 30%. Common offending medications include:[23]Awad A, Goh MS, Trubiano JA. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023 Jun;11(6):1856-68.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36893848?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011 Jul;124(7):588-97.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21592453?tool=bestpractice.com

Hospital admission is recommended for people with Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. Patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis should be managed in a burns unit or intensive care unit with:

Airway protection

Fluid and electrolyte resuscitation

Intravenous antibiotics for infection

Withdrawal of the culprit drug and all nonessential medications

Pain management

Nutritional support (e.g., parenteral nutrition)

Thermoregulation

Wound care and surgical debridement (removal) of dead tissue

Possibly intravenous immunoglobulins, cyclosporine, or corticosteroids.[19]Dodiuk-Gad RP, Chung WH, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015 Dec;16(6):475-93.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26481651?tool=bestpractice.com

The presentation of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) resembles the morbilliform drug eruption, but the patient is more ill, often with fever, abdominal pain, and facial swelling.[21]Duong TA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, et al. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs. Lancet. 2017 Oct 28;390(10106):1996-2011.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28476287?tool=bestpractice.com

Organs are infiltrated with eosinophils or lymphocytes. About 80% of patients have hepatic involvement. Respiratory, cardiac, and renal inflammation can also occur. Immediate withdrawal of the culprit medication is essential. Supportive care includes skin moisturization.[21]Duong TA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, et al. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs. Lancet. 2017 Oct 28;390(10106):1996-2011.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28476287?tool=bestpractice.com

Mortality may be 5% to 10%, and there may be no predictive factors for serious outcomes.[21]Duong TA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, et al. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs. Lancet. 2017 Oct 28;390(10106):1996-2011.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28476287?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Awad A, Goh MS, Trubiano JA. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023 Jun;11(6):1856-68.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36893848?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011 Jul;124(7):588-97.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21592453?tool=bestpractice.com

Sepsis

Sepsis is a spectrum of disease, where there is a systemic and dysregulated host response to an infection.[85]Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4968574

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26903338?tool=bestpractice.com

Maculopapular rash may be a feature in patients with sepsis. Associated conditions include staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, toxic shock syndrome, and meningococcemia.

Presentation ranges from subtle, nonspecific symptoms (e.g., feeling unwell with a normal temperature) to severe symptoms with evidence of multi-organ dysfunction and septic shock. Patients may have signs of tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, fever or hypothermia, poor capillary refill, mottled or ashen skin, cyanosis, newly altered mental state, or reduced urine output.[86]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng51

Sepsis and septic shock are medical emergencies.

Risk factors for sepsis include: age under 1 year, age over 75 years, frailty, impaired immunity (due to illness or drugs), recent surgery or other invasive procedures, any breach of skin integrity (e.g., cuts, burns), intravenous drug misuse, indwelling lines or catheters, and pregnancy or recent pregnancy.[86]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng51

Early recognition of sepsis is essential because early treatment improves outcomes.[86]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng51

[87]Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021 Nov 1;49(11):e1063-143.

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005337

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34605781?tool=bestpractice.com

[Evidence C]4f7250d3-c115-43c3-b842-c21d8b92a391guidelineCWhat are the effects of early versus late initiation of empiric antimicrobial treatment in adults with or at risk of developing sepsis or severe sepsis?[86]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng51

[Evidence C]0fe7315e-0958-433a-966d-c17a41bf5801guidelineCWhat are the effects of early versus late initiation of empiric antimicrobial treatment in children with or at risk of developing sepsis or severe sepsis?[86]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng51

However, detection can be challenging because the clinical presentation of sepsis can be subtle and nonspecific. A low threshold for suspecting sepsis is therefore important. The key to early recognition is the systematic identification of any patient who has signs or symptoms suggestive of infection and is at risk of deterioration due to organ dysfunction. Several risk stratification approaches have been proposed. All rely on a structured clinical assessment and recording of the patient’s vital signs.[86]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng51

[88]Royal College of Physicians. National early warning score (NEWS) 2: standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. December 2017 [internet publication].

https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/national-early-warning-score-news-2

[89]American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Expert Panel on Sepsis. DART: an evidence-driven tool to guide the early recognition and treatment of sepsis and septic shock [internet publication].

https://poctools.acep.org/POCTool/Sepsis(DART)/276ed0a9-f24d-45f1-8d0c-e908a2758e5a

[90]Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Statement on the initial antimicrobial treatment of sepsis. Oct 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Statement_on_the_initial_antimicrobial_treatment_of_sepsis_V2_1022.pdf

[91]Schlapbach LJ, Watson RS, Sorce LR, et al. International consensus criteria for pediatric sepsis and septic shock. JAMA. 2024 Feb 27;331(8):665-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38245889?tool=bestpractice.com

It is important to check local guidance for information on which approach your institution recommends. The timeline of ensuing investigations and treatment should be guided by this early assessment.[90]Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Statement on the initial antimicrobial treatment of sepsis. Oct 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Statement_on_the_initial_antimicrobial_treatment_of_sepsis_V2_1022.pdf

Treatment guidelines have been produced by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign and remain the most widely accepted standards.[87]Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021 Nov 1;49(11):e1063-143.

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005337

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34605781?tool=bestpractice.com

[92]Surviving Sepsis Campaign. Hour-1 bundle: initial resuscitation for sepsis and septic shock. 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.sccm.org/sccm/media/PDFs/Surviving-Sepsis-Campaign-Hour-1-Bundle.pdf

Recommended treatment of patients with suspected sepsis is:

Measure lactate level, and remeasure lactate if initial lactate is elevated (>18 mg/dL [>2 mmol/L]).

Obtain blood cultures before administering antibiotics.

Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics early (with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] coverage if there is a high risk of MRSA) for adults with possible septic shock or a high likelihood for sepsis.

For adults with sepsis or septic shock at high risk of fungal infection, empiric antifungal therapy should be administered.

Begin rapid administration of crystalloid fluids for hypotension or lactate level >36 mg/dL (>4 mmol/L). Consult local protocols.

Administer vasopressors peripherally if hypotensive after fluid resuscitation to maintain mean arterial pressure ≥65 mmHg, rather than delaying initiation until central venous access is secured. Norepinephrine (noradrenaline) is the vasopressor of choice.

For adults with sepsis-induced hypoxemic respiratory failure, high-flow nasal oxygen should be given.

Ideally these interventions should all begin in the first hour after sepsis recognition.[92]Surviving Sepsis Campaign. Hour-1 bundle: initial resuscitation for sepsis and septic shock. 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.sccm.org/sccm/media/PDFs/Surviving-Sepsis-Campaign-Hour-1-Bundle.pdf

For adults with possible sepsis without shock, if concern for infection persists, antibiotics should be given within 3 hours from the time when sepsis was first recognized.[87]Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021 Nov 1;49(11):e1063-143.

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005337

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34605781?tool=bestpractice.com

For adults with a low likelihood of infection and without shock, antibiotics can be deferred while continuing to closely monitor the patient.[87]Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021 Nov 1;49(11):e1063-143.

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005337

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34605781?tool=bestpractice.com

For more information on sepsis, see Sepsis in adults and Sepsis in children.

Bacterial toxin-mediated erythemas

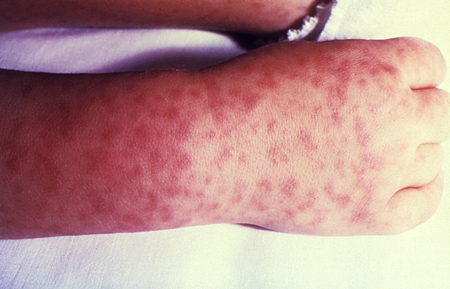

Toxin-mediated erythemas include staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, toxic shock syndrome, and scarlet fever.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Morbilliform rash (resembling measles) resulting from toxic shock syndromeCourtesy of the CDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and toxic shock syndrome

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is more likely in children ages 5 years or younger, while toxic shock syndrome is more common in postsurgical patients and occasionally is associated with menstruation.

Both are characterized by high fever, hypotension, and a desquamating macular rash. Erythema and edema of palms and soles, flexural accentuation of the rash, petechial hemorrhages, mucous membrane hyperemia, and strawberry tongue may also occur.[25]Drago F, Ciccarese G, Gasparini G, et al. Contemporary infectious exanthems: an update. Future Microbiol. 2017 Feb;12:171-93.

https://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/10.2217/fmb-2016-0147

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27838923?tool=bestpractice.com

The diagnosis is primarily clinical, as blood and fluid cultures are generally negative, though the clinical setting allows differentiation.

Management includes parenteral antibiotics and intensive supportive therapy.

Scarlet fever

Approximately 90% of scarlet fever cases occur in children under 10 years old.[61]UK Health Security Agency. Scarlet fever: symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. Mar 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/scarlet-fever-symptoms-diagnosis-treatment/scarlet-fever-factsheet

It is usually a mild illness, but is highly infectious.

Presents with a generalized, erythematous rash, which feels like sandpaper and is often preceded by a sore throat (pharyngitis, tonsillitis).

Pharyngeal erythema with exudates, palatal petechiae, and a red, swollen (strawberry) tongue are suggestive features.

Clinicians are advised to maintain a high index of suspicion, as early recognition and prompt initiation of specific and supportive therapy for patients with invasive group A streptococcal infection can be life-saving.

Prompt treatment of scarlet fever with antibiotics is recommended to reduce risk of possible complications, including invasive group A streptococcus, and to limit onward transmission.

In countries such as the UK, where rapid antigen detection tests (RADTs) for scarlet fever are not readily available, test confirmation of group A streptococcus infection is not required before starting antibiotics in patients with a clinical diagnosis of scarlet fever.[62]UK Health Security Agency. Guidance on scarlet fever: managing outbreaks in schools and nurseries. Apr 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/scarlet-fever-managing-outbreaks-in-schools-and-nurseries

In countries where RADTs for scarlet fever are available, a positive test result may be required before starting antibiotics (patients with clear viral symptoms don't need testing for group A streptococcal bacteria).[63]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Group A strep infection: clinical guidance for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/group-a-strep/hcp/clinical-guidance/strep-throat.html

If there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, obtain a throat swab prior to commencing antibiotics.[63]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Group A strep infection: clinical guidance for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Mar 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/group-a-strep/hcp/clinical-guidance/strep-throat.html

[64]UK Health Security Agency. Group A streptococcal infections: activity during the 2022 to 2023 season. Jun 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/group-a-streptococcal-infections-activity-during-the-2022-to-2023-season

[65]Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55(10):e86-102.

https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/55/10/e86/321183?login=false

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22965026?tool=bestpractice.com

[66]Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, et al. Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the Interdisciplinary Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and the Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2009 Mar 24;119(11):1541-51.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.191959

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19246689?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment of scarlet fever with antibiotics based on clinical diagnosis alone should follow in-country clinical guidelines.

According to the UK Health Security Agency, notifications of scarlet fever and invasive group A streptococcus (iGAS) disease in England were higher than expected from September 2022 to February 2023, with the peak observed in December 2022.[64]UK Health Security Agency. Group A streptococcal infections: activity during the 2022 to 2023 season. Jun 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/group-a-streptococcal-infections-activity-during-the-2022-to-2023-season

[67]UK Health Security Agency. Update on scarlet fever and invasive group A strep. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ukhsa-update-on-scarlet-fever-and-invasive-group-a-strep-1

The notifications have significantly reduced since then and are now in line with the expected number for the time of year.[64]UK Health Security Agency. Group A streptococcal infections: activity during the 2022 to 2023 season. Jun 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/group-a-streptococcal-infections-activity-during-the-2022-to-2023-season

Other countries experiencing an increased incidence of scarlet fever and iGAS disease during this period include France, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Sweden. The increase was particularly marked during the second half of 2022.[68]World Health Organization. Increased incidence of scarlet fever and invasive group A Streptococcus infection - multi-country. Dec 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON429

Meningococcemia

A maculopapular eruption may be an early presenting sign of meningococcemia and is distinct from the more classic petechial or coalesced purpuric eruption that is frequently found later in the disease process. The maculopapular eruption is transient, lasting for a few hours to no more than 48 hours, and resembles a wide variety of viral exanthems. Given the severity of this disease process it is important to consider early meningococcemia in the possible differentials when evaluating a patient with maculopapular eruption.

History factors to assess include:

Living conditions (more common in close living conditions such as college dormitories, prisons)

Immune status (prior immunization; people with immunization >10 years ago, young children, and older people may have inadequate immunity).

Fever and nuchal rigidity are generally present.

This infectious disorder is treated as an emergency with empiric antibiotic therapy and supportive therapy. The choice of antibiotic is guided by local susceptibility patterns, among other clinical factors.

Rickettsial infection (Rocky Mountain spotted fever)

Fever and generalized rash in the summer or fall is seen 1 week after outdoor activities in which a tick bite might occur.

Malaise, myalgia, and headache are common.

There is a generalized petechial rash involving the palms and soles. The rash characteristically starts on the wrists and ankles and spreads to the trunk.[70]Gottlieb M, Long B, Koyfman A. The evaluation and management of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the emergency department: a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2018 Jul;55(1):42-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29685474?tool=bestpractice.com

Approximately half of patients do not recall tick exposure.[70]Gottlieb M, Long B, Koyfman A. The evaluation and management of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the emergency department: a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2018 Jul;55(1):42-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29685474?tool=bestpractice.com

Serology can confirm the diagnosis.

Mortality is >20% in untreated cases.[93]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fatal cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in family clusters-three states, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004 May 21;53(19):407-10.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5319a1.htm

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15152183?tool=bestpractice.com

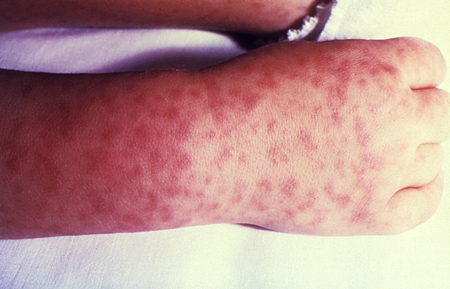

Patients are treated empirically with doxycycline (preferred).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic spotted rash of Rocky Mountain spotted feverCourtesy of the CDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

Kawasaki disease

Kawasaki disease (mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome) is an acute multisystem febrile disease that primarily affects children ages <5 years.[77]McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Apr 25;135(17):e927-99.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28356445?tool=bestpractice.com

The cause is unknown, though an infectious etiology is surmised.

The peak incidence is winter to late spring.

Diagnostic criteria include fever for 5 days plus at least four of the following five signs:[77]McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Apr 25;135(17):e927-99.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28356445?tool=bestpractice.com

[78]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng143

Conjunctival injection

Cervical lymphadenopathy, usually unilateral

Oropharyngeal changes (including hyperemia, oral fissures, cracked lips, and strawberry tongue)

Peripheral extremity changes (including desquamation of hands and feet, erythema, edema)

Polymorphous rash.

The rash is typically generalized and maculopapular, without petechiae; perineal erythema is particularly pronounced. The rash resembles a viral exanthem, though recognition is critical due to the possibly life-threatening complications of untreated Kawasaki disease:

Cardiac involvement (the most serious complication), including aneurysms in the coronary arteries (the most common cause of death), myocarditis, and congestive heart failure

Multi-organ involvement (common) affecting the central nervous system, eyes, kidney, and gastrointestinal system (including hydrops of the gallbladder).

Vasculitis of small and medium-sized vessels contributes to the pathology.

Diagnosis is made clinically, as no specific diagnostic test is available.[77]McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Apr 25;135(17):e927-99.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28356445?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment generally includes intravenous immune globulin and aspirin.[77]McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Apr 25;135(17):e927-99.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28356445?tool=bestpractice.com

Ebola virus

Maculopapular rash developed early in approximately 25% to 52% of patients in previous outbreaks,[45]Kortepeter MG, Bausch DG, Bray M. Basic clinical and laboratory features of filoviral hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(suppl 3):S810-16.

http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/204/suppl_3/S810.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21987756?tool=bestpractice.com

However, it only developed in 1% to 5% of patients in the 2014 outbreak.[46]Dallatomasinas S, Crestani R, Squire JS, et al. Ebola outbreak in rural West Africa: epidemiology, clinical features and outcomes. Trop Med Int Health. 2015 Apr;20(4):448-54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25565430?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]WHO Ebola Response Team. Ebola virus disease in West Africa: the first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. N Engl J Med. 2014 Oct 16;371(16):1481-95.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1411100#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25244186?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]Lado M, Walker N, Baker P, et al. Clinical features of patients isolated for suspected Ebola virus disease at Connaught Hospital, Freetown, Sierra Leone: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 Sep;15(9):1024-33.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26213248?tool=bestpractice.com

Frequently described as nonpruritic, erythematous, and maculopapular.

The eruption may begin focally, then become diffuse, generalized, and confluent.

Rash may become purpuric or petechial later on in the infection in patients with coagulopathy.[49]Nkoghe D, Leroy EM, Toung-Mve M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of filovirus infections. Int J Dermatol. 2012 Sep;51(9):1037-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22909355?tool=bestpractice.com

May be difficult to discern the rash in dark-skinned individuals.

The mainstay of treatment is early recognition of infection coupled with effective isolation and best available supportive care in a hospital setting.

Therapeutic antiviral monoclonal antibodies are available. The World Health Organization strongly recommends either atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab (also known as REGN-EB3) or ansuvimab (also known as mAb114) for patients with confirmed Zaire ebolavirus infection, and neonates ages ≤7 days with unconfirmed infection who are born to mothers with confirmed Zaire ebolavirus infection.[94]World Health Organization. Therapeutics for Ebola virus disease. Aug 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240055742

Dengue hemorrhagic fever

Mosquito-borne viral infection caused by any one of four closely related dengue viruses. Dengue has traditionally been classified as dengue fever (DF), dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), or dengue shock syndrome (DSS).[95]World Health Organization. Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. 2009 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547871

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23762963?tool=bestpractice.com

Dengue infection has three distinct phases:[95]World Health Organization. Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. 2009 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547871

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23762963?tool=bestpractice.com

Febrile

Critical

Convalescent.

The febrile phase is characterized by a sudden high-grade fever and dehydration that can last from 2 to 7 days.[95]World Health Organization. Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. 2009 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547871

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23762963?tool=bestpractice.com

The critical phase is characterized by plasma leakage, bleeding, shock, and organ impairment and lasts for approximately 24 to 48 hours. It usually starts around the time of defervescence (although this does not always occur), around days 3 to 7 of the infection. The following warning signs indicate that a patient with dengue infection is about to enter the critical phase of infection:[95]World Health Organization. Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. 2009 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547871

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23762963?tool=bestpractice.com

Abdominal pain or tenderness

Persistent vomiting

Clinical fluid accumulation (e.g., ascites, pleural effusion)

Mucosal bleeding

Lethargy/restlessness

Liver enlargement >2 cm

Laboratory: increase in hematocrit with rapid decrease in platelet count.

Patients with DHF/DSS go through all three stages; however, patients with DF bypass the critical phase.[95]World Health Organization. Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. 2009 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547871

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23762963?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with established warning signs, or in the critical phase of infection, with severe plasma leakage (with or without shock), severe hemorrhage, or severe organ impairment (e.g., hepatic or renal impairment, cardiomyopathy, encephalopathy, or encephalitis) require emergency medical intervention. Access to intensive care facilities and blood transfusion should be available. Rapid administration of intravenous crystalloids and colloids is recommended, according to algorithms produced by the World Health Organization.[95]World Health Organization. Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. 2009 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547871

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23762963?tool=bestpractice.com

[96]World Health Organization. Comprehensive guidelines for prevention and control of dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. 2011 [internet publication].

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204894

[97]World Health Organization. Handbook for clinical management of dengue. 2012 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241504713