History and exam

Other diagnostic factors

common

twin birth

unvaried supine sleep and resting position

Can perpetuate torticollis and plagiocephaly due to gravitational forces allowing head to fall to the side of the flattened occipital area, which is contralateral to the affected sternocleidomastoid.

decreased prone awake time

Children with CMT often dislike the prone position, but this position is important to prevent progression of CMT and plagiocephaly. Prone play also encourages elongation of both sternocleidomastoid muscles.[16]

head tilt

Head is tilted to the side of the affected sternocleidomastoid.

head rotated with decreased active rotation to affected side

Head typically rests in rotation contralateral to affected sternocleidomastoid. Active rotation to the affected side is limited.

decreased head righting to contralateral side

Head righting to the contralateral side is difficult, likely as the contralateral neck muscles become weakened due to persistent passive stretch.[16]

sternocleidomastoid mass

ipsilateral shoulder elevation

The ipsilateral shoulder may be elevated and the associated upper trapezius muscle may be taut.

plagiocephaly/craniofacial asymmetry

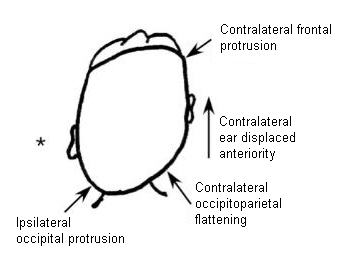

Associated plagiocephaly of varying degrees has been found in up to 90% of children with CMT.[2][8] Asymmetric occipital plagiocephaly is often the first deformity noted. Plagiocephaly and craniofacial asymmetry do not occur in isolation from each other, but severity does vary. Findings may also include ipsilateral occipital flattening, contralateral frontal protrusion, ipsilateral temporal protrusion, ipsilateral zygoma flattening, anterior displacement of the contralateral ear, inferior displacement of the ipsilateral orbit, and mandibular asymmetry.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vertex view of a head depicting typical findings of plagiocephaly associated with congenital muscular torticollis. Note the typical parallelogram shape due to asymmetric external compressive forces and associated growth. *Denotes the side of the shortened sternocleidomastoid and resultant torticollisPrepared by Dr Joyce L. Oleszek; used with permission [Citation ends].

uncommon

hypertropia on contralateral side

Present in superior oblique palsy, in which infants tilt their head away from the weak superior oblique muscle. This abnormality is not always obvious.

Risk factors

strong

plagiocephaly

Can develop at birth resulting from in utero or intrapartum molding, or postnatally resulting from lack of varied supine positioning.

If deformity perpetuates due to the supine position, gravity will force the head to turn to the side of the flattened occiput. Torticollis can then result from this persistent unidirectional positioning.

weak

breech delivery

cesarean section delivery

twin A (lower in utero)

complicated deliveries (forceps or vacuum)

birth trauma

Birth trauma theory proposes that a congenitally shortened sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle is torn at birth, with the formation of a hematoma and subsequent development of fibrous contracture.[19] However, hemorrhagic inflammatory reaction and myofiber disruption are not often found histologically in the SCM mass.[20]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer