Tests

1st tests to order

flexible laryngoscopy

Test

Should be performed in all patients to assess laryngeal anatomy and related comorbidity (e.g., mucosal inflammation as evidence of GERD).

Topical anesthesia is applied to the nasal mucosa so the upper airway and larynx may be examined while the child is fully awake. This allows assessment of vocal cord movement. However, flexible laryngoscopy does not provide for a reliable assessment of the subglottis or more distal airway.

Laryngeal features may include an elongated or tubular epiglottis with collapse into the glottic airway on inspiration (12%).[22] The aryepiglottic folds may be short (15% of cases), with posterior angling of the epiglottis.[22][11] The arytenoids may also seem tall due to redundant mucosa with anterior and medial collapse of the arytenoids, cuneiforms, corniculate cartilage, or aryepiglottic folds into the airway (57%).[22]

These features may occur separately or in combination (15%).[22]

Result

dynamic collapse of the supraglottic tissues on inspiration; visible narrowing and obstruction of the supraglottic airway; anatomic anomalies; evidence of GERD

Tests to consider

rigid laryngobronchoscopy

Test

With flexible laryngoscopy, subglottic views cannot be reliably obtained to exclude synchronous airway pathology. Furthermore, LM can only be confirmed with dynamic views obtained during spontaneous respiration, under a general anesthetic, usually as the general anesthesia lightens.

Rigid laryngobronchoscopy can both confirm the findings of flexible laryngoscopy and reliably exclude coexisting airway lesions (e.g., tracheomalacia, subglottic stenosis, or vocal cord palsy). The incidence of second lesions has been reported to be between 12% and 64%.[22][8][23][24][25]

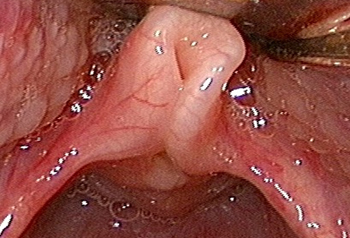

Some authors advise a full airway assessment in all patients with LM to ensure potentially life-threatening pathology is not overlooked, whereas others proceed with rigid endoscopy only if there is apnea, failure to thrive, or clinical suspicion of a second lesion.[22][24][26] The procedure is performed in all cases requiring endoscopic surgery for treatment of LM.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Typical example of laryngomalaciaFrom the personal teaching collection of Simone J. Boardman, MBBS, FRACS (OHNS) and C. Martin Bailey, BSc, FRCS, FRCSEd [Citation ends].

Result

collapse of the supralaryngeal tissues during inspiration is evident when the patient is breathing spontaneously; may show additional pathology

FEES testing

Test

Videofluoroscopic swallowing studies or functional endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) testing is used in assessing feeding problems to detect episodes of laryngeal penetration or aspiration.

Result

may reveal swallowing abnormalities

polysomnography

Test

May be considered to determine associated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Sleep studies assist in the ongoing management of patients with LM and OSA, particularly in following the progress and making management decisions for complex patients with multiple medical problems.

Result

variable; may show increased respiratory disturbance index (RDI)

chest x-ray

Test

May provide evidence of synchronous airway pathology or aspiration.

Result

variable; may show cavities or new infiltrate in dependent lung fields

lateral neck radiograph

ECG

Test

Order in patients with clinical findings suggestive of an underlying genetic syndrome (e.g., Down syndrome) associated with congenital heart disease.

Result

variable; may show evidence of congenital heart disease

echocardiogram

Test

Order in patients with clinical findings suggestive of an underlying genetic syndrome (e.g., Down syndrome) associated with congenital heart disease.

Result

variable; may show evidence of congenital heart disease

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer