Approach

Cholangiocarcinoma usually presents late, with advanced disease. The clinical presentation depends largely on the location of the tumor: that is, intrahepatic or extrahepatic (perihilar and distal). Some cholangiocarcinomas are found unexpectedly as a result of an ultrasound scan or liver profile performed for a different reason. However, imaging alone is not sufficient to make a diagnosis. Pathologic diagnosis of operative specimens is required for a definitive diagnosis.[7]

History and physical examination

The typical patient is usually ages >50 years. Other key risk factors that should be elicited during history-taking include history of cholangitis, choledocholithiasis, cholecystolithiasis, other structural disorders of the biliary tract, ulcerative colitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, liver fluke infection, liver disease, hepatitis C virus, HIV infection, hepatitis B virus, and exposure to thorium dioxide or other toxins/medications (e.g., polychlorinated biphenyls [PCBs], isoniazid, oral contraceptive pills, and to chronic typhoid carriers).

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

Usually presents as a mass lesion; obstructive jaundice symptoms are rare. Some nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort, malaise, and nausea, can be present.

Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (perihilar and distal)

Usually presents with the symptoms of obstructive jaundice (around 90% of patients): pale stool, dark urine, and pruritus. During the early stages of the tumor, when the biliary tract has not been obstructed, some nonspecific symptoms including vague abdominal pain, nausea, and malaise can be present. In advanced disease, jaundice, pruritus, weight loss, anorexia, fatigue, abdominal mass, hepatomegaly, and Courvoisier sign (painless palpable gallbladder and jaundice) may be present.[3][30][31]

Laboratory investigations

No blood tests are diagnostic for cholangiocarcinoma. Liver function tests (LFTs) should be ordered, as liver biochemical abnormalities are consistent with obstructive jaundice. Certain serum tumor markers have shown some utility as an aid to other diagnostic tests; however, they are not used as a screening test because of the lack of sensitivity and specificity.

It is recommended that the following blood tests are ordered:

Bilirubin (conjugated bilirubin is elevated in obstructive jaundice)

Alk phos (usually elevated; suggests obstructive [or cholestatic] pattern of elevated LFTs)

Gamma-GT (usually elevated; suggests obstructive [or cholestatic] pattern of elevated LFTs)

Aminotransferase (may be minimally elevated)

Prothrombin time (usually increased)

CA 19-9 (elevated in up to 85% of patients)

CA-125 (elevated; detectable in up to 65% of patients)

CEA (elevated)

Imaging

A specific challenge in the management of cholangiocarcinoma is the lack of reliable imaging. No consensus exists about the various combinations of imaging modalities. Typically, ultrasound is followed by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). High-resolution cross-sectional imaging of the liver is essential for evaluation of the primary mass, presence of metastases, vascular invasion, resectability, and accurate staging.[7][32]

Abdominal ultrasound

The initial test to evaluate a patient with obstructive jaundice. This is because of the ubiquitous availability of this modality and the capacity to exclude common causes, such as choledocholithiasis. Ultrasound allows for the visualization of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary ducts, thus demonstrating the level of potential obstruction as well as the caliber and patency of the portal vasculature. However, the sensitivity of ultrasound in specifically detecting cholangiocarcinoma is low.[32] When additional criteria are employed, such as clinical history and presenting symptoms, a focused ultrasound to evaluate the biliary tree and portal venous structures can have a high sensitivity. However, used alone, ultrasound has a low level of accuracy in assessing any specific diagnoses.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gallbladder ultrasound of mass (arrows)From the collection of Dr Joseph Espat; used with permission [Citation ends].

Abdominal CT/MRI

Ultrasound is usually followed by an abdominal CT, which will confirm the presence of a mass and whether or not there is obstruction, manifested as intrahepatic or extrahepatic ductal dilation. Abdominal MRI is often utilized to differentiate between solid and cystic biliary contents. Furthermore, MRI can provide additional information regarding tumor size, extent of bile duct involvement, vascular patency, extrahepatic extension, nodal or distant metastases, and the presence of lobar atrophy. MRI diagnostic performance is comparable to CT.[33] Preoperative imaging with MR angiography is a noninvasive method for staging cholangiocarcinoma, and therefore also helps determine resectability.[34]

Cholangiography

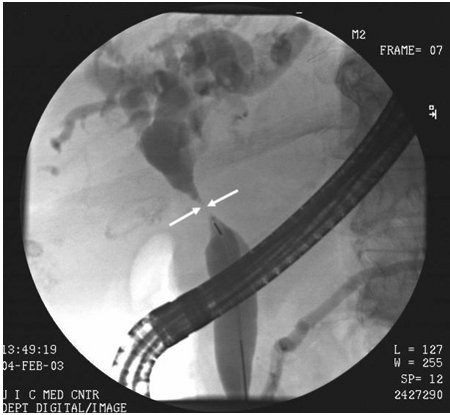

Imaging findings are then correlated with laboratory findings, and if a provisional diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma is made, the patient may have further imaging by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), or percutaneous transhepatic catheterization (PTC).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ERCP image of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Klatskin tumor with stricture of duct bifurcation (arrows)From the collection of Dr Joseph Espat; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ERCP image of hepatic duct cholangiocarcinoma with duct stricture (arrows)From the collection of Dr Joseph Espat; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ERCP image of hepatic duct cholangiocarcinoma with duct stricture (arrows)From the collection of Dr Joseph Espat; used with permission [Citation ends].

The procedure of choice in further evaluating a cholangiocarcinoma is dependent on the need for biliary decompression.[34] ERCP is both diagnostic and therapeutic (procedures such as biopsy and decompressive stent placement can be performed, and brushings can be taken to acquire samples for cytologic and immunohistochemical examination).[35] However, it also requires the ability to cannulate the ampulla of Vater. If cannulation of the ampulla is not possible and biliary drainage is needed, then PTC is the treatment of choice. MRCP is the recommended procedure if only anatomic visualization of the bile ducts distal to the stricture is required. The use of ERCP does not exclude MRCP. EUS allows examination of the extrahepatic bile duct and tissue acquisition by fine needle aspiration from the primary mass and lymph nodes.[7] There is currently no consensus in the literature with regard to choosing between these interventions.

ERCP is an endoscopic procedure. The endoscope is introduced into the second part of the duodenum, and contrast dye is injected into the bile ducts. If a tumor is present, a filling defect or area of narrowing will be seen on the x-ray. During the procedure, samples of the tumor can be taken by brush or biopsy. These should be sent to pathology for diagnosis. A bile sample can be sent for cytologic analysis. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy suggests using fluoroscopic-guided biopsy sampling in combination with brush cytology in patients with biliary strictures of undetermined etiology undergoing ERCP.[36] An ERCP also allows stent insertion for palliative purposes. The risks of ERCP include those associated with sedation, damage or perforation of the gut wall, bleeding, allergic reaction to the dye, and pancreatitis. Endoscopists performing such procedures should be aware of associated adverse-event rates and their risk factors to optimize the informed consent process and patient selection.[37]

MRCP can enable evaluation of the biliary tree proximal and distal to an obstruction. It can therefore provide the surgeon with valuable information, such as if there is local invasion of the surrounding structures by the tumor. MRCP has the advantage of being noninvasive and does not carry the risks that ERCP or PTC do. The main disadvantage of MRCP is that it is diagnostic only and no therapeutic options can be performed.

PTC is an invasive procedure that is used when the tumor causes complete obstruction of the biliary tree and ERCP is unable to assess the biliary tree proximal to the tumor. It is also the imaging modality of choice when the tumor is persistent or has recurred. If a tumor is found to be unresectable, a stent can be placed during the procedure for palliation purposes. A bile sample can be taken during the procedure and sent for cytologic analysis.[32] The risks of PTC are bleeding, infection, and temporary or permanent renal impairment. Endoscopic-ultrasound guided, or percutaneous, biopsies should be avoided in patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma who are potential transplant candidates, due to the risk of tumor dissemination.[7]

Positron emission tomography

Positron emission tomography (PET) is useful in the diagnosis of many cancers; however, current literature cautions against the use of PET for determining the malignant potential of primary liver cancers. Literature on PET more strongly supports the role of restaging of hepatobiliary malignancies and identifying metastatic disease.[7][38]

Immunostaining

Cholangiocarcinoma can present as mixed with hepatocellular cancer. These tumors are more aggressive. Immunostaining of pathologic specimens to detect markers of hepatocellular carcinoma (e.g., GPC3, HSP70, and glutamine synthetase) or progenitor cell features (e.g., K19, EpCAM) is recommended to distinguish intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma from mixed hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma if this information will change management.

Emerging tests

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) involves the use of infrared light to obtain scans that can correlate with histology. Peroral cholangioscopy is currently in development for diagnostic imaging and for pathologic diagnosis. Duodenoscope-assisted cholangioscopy evaluates the inside of the bile duct using the duodenal approach, as would be used for a stent placement.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer