Approach

Bruxism can represent a normal variation of behavior in otherwise healthy individuals, as well as a phenomenon associated with a number of clinical problems. A certain amount of bruxism-related motor activity is not necessarily pathologic, though it may reflect the presence of one more underlying conditions or factors.[2][15][47]

Approaches for assessing bruxism can be noninstrumental (history and clinical exam) or instrumental (using investigations). Instrumental approaches for sleep bruxism (SB) involve polysomnography (PSG) or electromyography (EMG) recordings, while ecologic momentary assessment (EMA) is a promising approach to awake bruxism (AB) diagnosis.[1][9]

The early clinical diagnosis of possible and probable bruxism is primarily based on noninstrumental methods which do not allow for SB and AB to be accurately distinguished.[1] Validated research diagnostic criteria for a definite diagnosis exist only for SB and are based on PSG recordings.[48][49] However, it is important to note these criteria were validated in a small sample of carefully selected individuals who may not be representative of the full spectrum of people with bruxism. Furthermore, PSG/SB criteria may only provide a partial picture of the complex range of jaw-muscle activities incorporated within the construct of bruxism and so are further limited in this regard.[50] No definitive criteria have yet been established for AB.

The assessment and diagnosis of bruxism is challenging given the subjectivity of self-reports and the divergent diagnostic criteria and outcomes reported in clinical research studies. Tools for standardizing bruxism assessment are in development but require further testing and are yet to be validated.[51][52]

Noninstrumental approach: history

History taking via structured questionnaires, interviews, and more general self-reported measures is useful to gather preliminary information on bruxism activities, the presence of clinical consequences, and possible risk factors. This information is a subjective view, but informs the later steps of diagnosis.[53]

Bruxism activities

The history should explore behaviors of teeth grinding and/or clenching as well as jaw bracing and/or thrusting during sleep and wakefulness.

It may be helpful for the patient (and any bed partners) to keep a diary to note the nature and frequency of these activities. Parents/caregivers should also be advised to keep a record of these behaviors in children.

Nonfunctional oral habits

Habits such as biting activities (chewing gum, tooth-tapping, nail-biting, object-biting e.g., pencils), and movements involving soft-tissues (cheek-, lip-, or tongue-biting, grimacing, tongue pushing against teeth, licking lips, tongue protrusion) may be present.[54] Association of these habits with bruxism has been reported, especially in children and adolescents, and they may suggest an anxious personality that is also associated with awake bruxism.[55][56]

Functional symptoms

Functional symptoms should be elicited. Prolonged clenching may be a causative factor for some symptoms, such as the difficulty to open the mouth wide on awakening.[57] Prolonged bruxism overload may also increase the frequency and duration of lock episodes in people with intermittent locking.[58]

Pain

The relationship between bruxism and pain in the jaw muscles and/or temporomandibular joints (TMJ) is controversial.[6] However, the presence of jaw muscle pain and fatigue in the morning may lead to a suspicion of sleep-time teeth clenching.

A history of pain symptoms in the orofacial pain area should be collected including:

Tooth soreness and/or hypersensitivity

If bruxism-related attrition reaches the dentine, the tooth pulp may become more sensitive to cold air or liquids.[54] However, this phenomenon is not pathognomonic, because it can also be caused by other conditions (e.g., dental malocclusion). In addition to hypersensitivity, people with bruxism may experience tooth soreness, especially in the morning after prolonged sleep-time clenching.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bruxism-related attrition reaching the dentine may result in tooth soreness and hypersensitivityFrom the collection of Dr Alessandro Bracci [Citation ends].

Jaw muscle pain

Both SB and AB may be associated with jaw muscle pain. The relationship is not linear, and depends on several factors. There is some consensus that clenching-type activity during the day is associated more with jaw pain than tooth grinding during sleep. If present, pain is often worst upon awakening.[59]

Temporomandibular joint pain

Investigations based on self-reported or clinical bruxism diagnosis showed a positive association with TMJ pain, although studies based on more quantitative and specific methods to diagnose bruxism showed much lower association with temporomandibular disorder (TMD) symptoms in general.[6]

Headache

Empiric observations suggest that bruxism may be associated with temporal headaches. Literature on the topic is scarce and mainly based on observations in children.[60]

When pain is present, its location and perceived intensity can be assessed using visual analog scales or the McGill Pain Questionnaire. The psychosocial effects of the pain should also be explored.[61][62]

Family and personal history

The history should explore any relevant family history. Twin studies and analyses of familial distribution indicate a genetic determinant in sleep bruxism.[43] However, because bruxism is a complex motor behavior, it is unlikely to be explained by a single gene expression, and genetic-environmental interaction is likely to be involved.[44]

Personal history of bruxism activities should also be elicited as bruxism may sometimes persist from childhood into adulthood.[44]

Risk factors for bruxism

Specific factors may influence bruxism onset or exacerbation and should, therefore, also be explored as part of patient history.

Medication and illicit drug use: use of medications (selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors, dopamine antagonists) and illicit drugs (ecstasy, cocaine) can contribute to the development of bruxism and should be specifically elicited.[40][41][42]

Smoking, caffeine, and alcohol consumption: all of these factors can exacerbate SB, although the specific mechanisms are unclear.[34][35]

Sleep disorders: obstructive sleep apnea and snoring have been indicated as strong risk factors for SB.[36][37]

Stress and anxiety: assessment of stress and anxiety levels should be undertaken as part of the history. Psychosocial factors (i.e., stress sensitivity, anxious personality traits) and psychopathologic symptoms (e.g., neuroticism) are linked to bruxism.[21][22][23][63]

Neurologic diseases: bruxism may be part of the clinical picture of other well-known primary motor disorders, such as dystonia, dyskinesia, extrapyramidal disorders, and other neurologic conditions.[45]

Noninstrumental approach: clinical exam

The clinical assessment for the diagnosis of probable bruxism includes a complete dental examination, an inspection of the cheek and tongue mucosa, and evaluation of the jaw muscles and TMJ.[1] It is not possible to discriminate clinically between signs of past and ongoing bruxism.

Teeth and periodontium signs

Tooth wear

Tooth wear is considered the typical bruxism sign, but is not a reliable diagnostic factor because of the high prevalence of tooth wear in populations of non-bruxing people.[5][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tooth enamel chippings, cracks, and fractures of natural teeth together with attrition, abfraction, and abrasion due to ceramicsFrom the collection of Dr Alessandro Bracci [Citation ends].

Tooth wear has a multifactorial etiology including: dental attrition (intrinsic mechanical tooth wear caused by tooth-to-tooth contact), abrasion (extrinsic mechanical tooth wear caused by a foreign element, such as a hard bristle toothbrush, rubbing on the teeth), abfraction (intrinsic mechanical tooth wear caused by occlusal forces such as bruxism), and erosion (extrinsic and intrinsic chemical tooth wear).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bruxism-related attrition reaching the dentine may result in tooth soreness and hypersensitivityFrom the collection of Dr Alessandro Bracci [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Erosion lesionFrom the collection of Dr Alessandro Bracci [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Erosion lesionFrom the collection of Dr Alessandro Bracci [Citation ends].

Reliable discrimination between the different causes of tooth wear is challenging due to the difficulties of distinguishing between functional and nonfunctional tooth wear patterns. Moreover, some forms of bruxism may not cause clinically detectable tooth wear.

The location and amount of tooth wear should be recorded, especially if evaluation on dental casts is used.[64] A useful tool, the Tooth Wear Evaluation System (TWES) 2.0, has been proposed which has been shown to have acceptable reliability.[65][66]

In people with bruxism, tooth wear often presents as wear facets on canines and incisors. Findings suggestive of bruxism include tooth wear affecting at least 1 sextant of the dentition, with enamel reduction to dentine and some loss of crown height.[5]

Tooth enamel chippings, cracks, and fractures of natural teeth

Despite not being pathognomonic of bruxism, signs of tooth enamel chipping, teeth fractures, or cracks may indicate the presence of bruxism activities. In particular, enamel chippings may be clinically relevant when occurring on multiple teeth.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tooth enamel chippingsFrom the collection of Dr Alessandro Bracci [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tooth fractureFrom the collection of Prof Daniele Manfredini [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tooth fractureFrom the collection of Prof Daniele Manfredini [Citation ends].

Dental restoration failures

These range in severity from detachment of esthetic fillings with poor retention, to fractures of composites or ceramics. Chipping of restorations and de-cementation of crowns and bridges may also be observed in people with bruxism.

For dental implants, bruxism is unlikely to be a risk factor for biologic complications (e.g., implant survival, bone loss, gingival attachment loss), but may be a risk factor for mechanical complications (e.g., screw loosening, fractures of restorations).[67][68]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: An example of a fracture of dental implant componentsFrom the collection of Dr Alessandro Bracci; used with permission [Citation ends].

Periodontal problems

Based on literature findings, there is no evidence of a direct relationship between bruxism and periodontal status (e.g., bone loss, gingival attachment loss, inflammation); however, patients may present with periodontal problems on exam.[69][70]

Mucosal signs

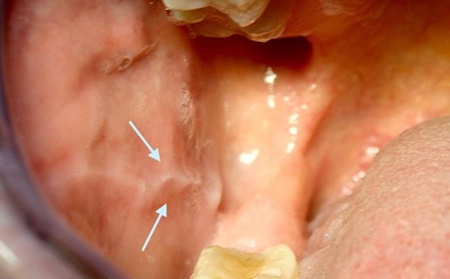

Linea alba (white line)

May be present. Linea alba is a hyperkeratosis of the oral mucosa in the cheeks, representing a sort of dental impression on the inside surface of the cheek. It is usually bilateral and is a common feature of patients with teeth clenching habits, such that it may be considered the main clinical marker of clenching-type bruxism. Its presence and severity depend, at least in part, on the teeth morphology. Intense and prolonged clenching may cause more marked signs on the cheek mucosa.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Linea alba (white line) is a hyperkeratosis of the oral mucosa in the cheeks, representing a dental impression on the inside surface of the cheekFrom the collection of Prof Daniele Manfredini [Citation ends].

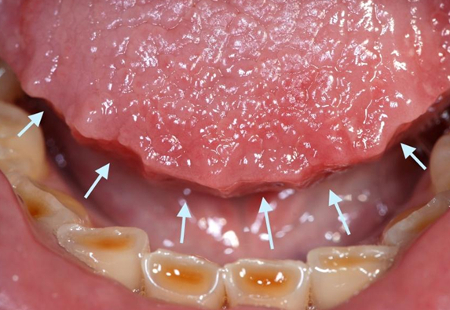

Tongue scalloping

Tongue mucosa may show indentations.[54] This sign features indented lateral tongue borders, usually bilateral and partly depending on the inclination of the antagonist teeth. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tongue scallopingFrom the collection of Dr Alessandro Bracci [Citation ends].

Traumatic lesions

Severe clenching may also be responsible for traumatic lesions of the tongue or cheek mucosae, initially manifesting with small petechial hemorrhages around the linea alba and possibly resulting in white lesions.

Another possible sign is unusual keratinization of the lip.

Muscle signs

Jaw muscle exam

The masticatory muscles (masseter and temporalis, in particular) should be tested for pain on palpation and during opening and closing of the jaw. In some patients, bruxism can sensitize the muscles, making palpation and normal oral functions, such as biting or wide jaw-opening, uncomfortable even in the absence of clinically relevant pain.[59]

Muscle hypertrophy

Repeated activation of jaw muscles can lead to a functional hypertrophy, most noticeably as a training effect on the masseter muscles.[54] It is likely that such hypertrophy is the result of prolonged jaw clenching in predisposed patients with short-faced morphology, and it has also been described (rarely) in the temporalis muscles.[71]

Palpation of the increase in jaw muscle volume with maximal voluntary contraction can give an indication of possible hypertrophy. Another possible approach to evaluation is visible hypertrophy when the muscles are relaxed, thus possibly affecting facial aesthetics.

TMJ signs

Disc and joint degeneration

The relationship between bruxism and TMD, has not been clarified.[6][72] The TMJ may be overloaded in conditions of prolonged clenching activities and this may put the joint at risk of disc abnormalities and articular degeneration.

The patient’s dental occlusion may exacerbate the negative effects of bruxism on the joints.[73][74] In cases of intermittent closed locking, locks occur more frequently and are of longer duration in the presence of bruxism.

TMJ pain

To confirm the presence of TMJ pain, positive dynamic/static tests, which have a high specificity but low sensitivity, should be used. To rule out TMJ pain, negative palpation tests which have a high sensitivity should be carried out.[75]

When TMJ pain is present, intensity assessment strategies should follow the same protocols as for pain in the jaw muscles.

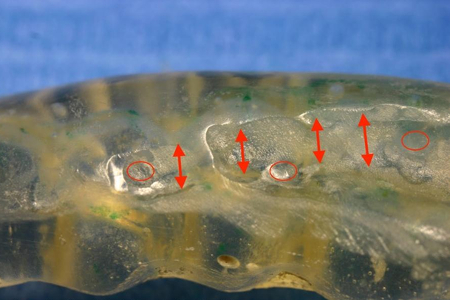

Oral appliances wear

The literature on the validity of examining wear on the oral appliances for the diagnosis of ongoing bruxism is poor. Nonetheless, such a method represents an option for clinicians to evaluate the presence (and type) of bruxism activities.

Patterns of wear differ from clenching-type to grinding-type movements, even if a combination of the two is also frequent.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oral appliance wearFrom the collection of Prof Daniele Manfredini [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oral appliance wearFrom the collection of Dr Alessandro Bracci [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oral appliance wearFrom the collection of Dr Alessandro Bracci [Citation ends].

Instrumental approaches: use of recording devices

The intensity and duration of specific masticatory muscle activity cannot be quantified easily via self-reported measures.[76] One of the limitations is that the bruxism-psyche relationship could alter self-reporting, reflecting distress rather than masticatory muscle activity.

Instrumental approaches for assessment are currently available for both forms of bruxism.

A definite diagnosis of bruxism as a motor phenomenon can be achieved through measurement of jaw muscle activity.[1]

In cases of SB, the relationship of bruxism with other sleep arousal parameters should be assessed with PSG, combined with audio and video recordings.[1] Alternatively, portable EMG devices for in-home recordings may be used to demonstrate masticatory muscle motor activity.

For AB, hour-long wake time EMG recordings are the theoretical standard of reference but are rarely practical. Alternative strategies for a definite diagnosis of AB come from recording techniques based on EMA, which require a real-time appraisal of AB behaviors at different recording moments during the day.[1][77]

EMG

Can provide evidence of AB and SB.

Some diagnostic strategies based on single- or multi-channel ambulatory EMG recordings have been proposed.[78][79][80]

Portable EMG recorders provide the clinician with the number of jaw muscle activities per hour during the sleep or awake state. They can be used in patients with self-reports of moderate to severe SB, excessive tooth wear, or repeated fractures/failures of dental restorations.

Portable devices offer easier availability and lower-level technical equipment with respect to PSG; however, costs limit their full introduction into the clinical setting.

A review of the diagnostic accuracy of portable EMG recorders, and validity testing showed that multi-channeled devices may be accurate even with a single night of use, while multiple nights with single-channel devices are required to achieve sufficient agreement with PSG/SB diagnosis.[32][78][80] If limited-channel ambulatory EMG monitoring of SB is used (which evaluates only facial muscles), care must be taken that other potential sleep disorders are not missed. Use of sleep disorder questionnaires, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaires, is advisable in this situation.

PSG

PSG shows the number of bruxism events per hour of sleep and is the definitive test for a SB diagnosis, but it has limited use due to high costs and very low availability.[1][81]

A SB event is defined as a contraction of the right masseter muscle exceeding 20% of maximum voluntary contraction (MVC). Based on its duration, an event can be classified as tonic (single EMG burst >2 seconds), phasic (three or more bursts lasting 0.25 to 2 seconds), or mixed (a combination of the two types).

Patients with self-reports of severe SB, pain, poor sleep, and other significant sleep disorders (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea) may be candidates for a PSG evaluation with a sleep specialist. Based on findings from a validation study, over 80% of people with severe bruxism are correctly identified by a PSG study.[49] See Diagnostic criteria.

EMA

EMA involves repeated, real-time sampling of subjective behaviors and experiences about jaw muscle activities at certain time points during wakefulness (e.g., symptoms, affect, behavior, feeling, cognition).[77] It is an alternative to wake-time EMG to achieve a definite AB diagnosis.[9]

Patients can use EMA to report the conditions of their jaw muscles such as relaxed jaw muscles, teeth contact, teeth-clenching, teeth-grinding, jaw-clenching without teeth contact (i.e., bracing).

Progress in smartphone technology has opened up a new era for EMA, as data collection for clinical and research purposes can now be conducted using a tool that is already a part of daily life for a large percentage of the population.[82][83]

The development of EMA strategies has allowed for the evaluation of real-time AB behavior frequency compared to the self-reported activities identified in questionnaires.[9]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer