Approach

Most patients with mild to moderate aortic coarctation are asymptomatic. However, severe coarctation may present with hypotension, cyanosis, and shock in the neonatal period once the ductus arteriosus closes.

History

In older patients a history of unexplained hypertension present from a young age may be elicited. These patients may have been treated unsuccessfully with antihypertensive medications. Claudication of the lower limbs may be present. In rare cases, an adult may present with intracranial hemorrhage from a ruptured berry aneurysm in the circle of Willis associated with aortic coarctation. Additionally, young individuals exhibiting hypertension in the upper limbs or experiencing leg fatigue during physical activities should be evaluated for coarctation of the aorta. These symptoms can indicate the presence of a significant narrowing even when other signs are not as apparent.[15]

Physical exam

May present with upper extremity hypertension and lower extremity hypotension.[16] If the upper extremity systolic blood pressure (BP) is >95 percentile for age or if the lower extremity pulses are diminished or absent, noninvasive BP measurements in all 4 extremities should be obtained. Attention should be given to ensure that the BP cuff fits appropriately (this often requires a different size for the upper and lower extremities).

Cardiac exam may be normal or a long systolic murmur may be heard at the left upper sternal border and over the back. A systolic ejection click may be heard if there is an associated bicuspid aortic valve.

Faint or absent femoral artery pulses or femoral artery pulses that are delayed when palpated simultaneously with upper extremity pulses should raise the suspicion of a coarctation.

Rarely the right subclavian artery may arise anomalously from the descending aorta after the area of coarctation. In this situation the right arm BP will be the same as the leg. Strong suspicion of coarctation should still prompt further evaluation.

Investigations

If aortic coarctation is suspected based on physical exam, early testing by echocardiography is required.[17]

In children the echocardiogram should be performed by a sonographer trained in congenital heart disease (CHD) or referral to a pediatric cardiologist should be made.[18] The demonstration of a gradient across a narrowed segment of the aorta confirms the diagnosis.

ECG should be performed as part of the initial workup in patients with suspected CHD or hypertension. Chest x-ray is important to determine severity, such as evidence of heart failure.[17]

Echocardiography is typically utilized first and in general is able to define the anatomy and guide management.[17] Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), depending on the local expertise of the center, are often used to assist in the diagnosis and interventional planning. Rarely, cardiac catheterization with angiography is used if the diagnosis remains uncertain after noninvasive studies.[17][19]

Routine evaluation for associated intracardiac anomalies should be part of the initial echocardiogram, with particular care paid to the aortic valve morphology and aortic root. Particular attention should be given to commonly coexisting conditions such as ventricular septal defects, bifoliate aortic valves, aortic and subaortic stenosis, and mitral valve abnormalities, especially when the aortic coarctation is adjacent to the arterial duct or involves a nonconfluent aortic arch.[15] Older patients diagnosed with aortic coarctation should also be screened for intracranial aneurysms by MRA or CT angiography.[20] Consideration for genetic evaluation is also warranted when there are dysmorphic features, multiple organ abnormalities, or additional intracardiac or vascular abnormalities.

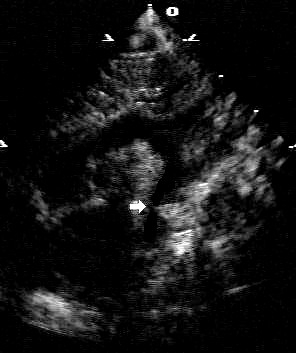

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Two-dimensional suprasternal notch view of the aortic arch. Focal narrowing of the aortic arch (arrow) in the typical juxtaductal regionFrom the personal collection of Jeffrey Gossett, MD, Children's Memorial Hospital, Northwestern University, Chicago; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Addition of color Doppler shows turbulent higher velocity flow after the obstructed areaFrom the personal collection of Jeffrey Gossett, MD, Children's Memorial Hospital, Northwestern University, Chicago; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Addition of color Doppler shows turbulent higher velocity flow after the obstructed areaFrom the personal collection of Jeffrey Gossett, MD, Children's Memorial Hospital, Northwestern University, Chicago; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Three-dimensional computed tomographic reconstruction visualized from posterior to anterior. The area of coarctation is well seen (arrow)From the personal collection of Jeffrey Gossett, MD, Children's Memorial Hospital, Northwestern University, Chicago; used with permission [Citation ends].

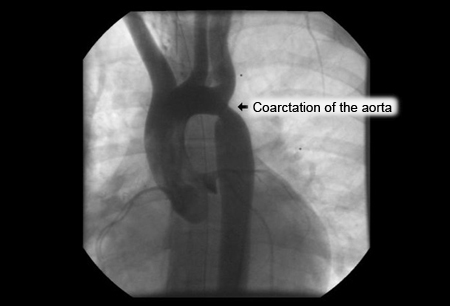

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Three-dimensional computed tomographic reconstruction visualized from posterior to anterior. The area of coarctation is well seen (arrow)From the personal collection of Jeffrey Gossett, MD, Children's Memorial Hospital, Northwestern University, Chicago; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Angiography in the ascending aorta shows a focal area of narrowing after the left subclavian arteryFrom the personal collection of Jeffrey Gossett, MD, Children's Memorial Hospital, Northwestern University, Chicago; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Angiography in the ascending aorta shows a focal area of narrowing after the left subclavian arteryFrom the personal collection of Jeffrey Gossett, MD, Children's Memorial Hospital, Northwestern University, Chicago; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer