Etiology

In both children and adults, recurrent infections resulting from anatomic abnormalities are a major factor in the development of chronic pyelonephritis and renal failure. In chronic interstitial nephritis, the primary etiologic factors are vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) - a condition in which urine flows backward from the bladder to one or both ureters and sometimes to the kidneys - and obstruction.[11]

Chronic pyelonephritis may result from inadequate treatment or recurrence of acute pyelonephritis, constituting a progressive localized immune response to bacteria that have long since been eradicated.[12] One of the main causes of chronic pyelonephritis in children is primary VUR, a common condition associated with varying degrees of renal damage.[6][7] Patients may have a history of VUR and frequent urinary tract infections (UTIs). In children, there is a strong association between renal scarring and recurrent UTIs.[13] The developing kidney appears to be very susceptible to damage, but this susceptibility appears to be age-dependent. Renal scarring induced by UTIs is rarely seen in adult kidneys.[14][15]

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP) is a severe, atypical, and relatively rare form of chronic pyelonephritis that is usually unilateral and is associated with prolonged obstructive uropathy.[16] Obstruction and infection lead to enlargement of the kidney. Proteus species are the causative pathogens in 60% of cases.[16]

Emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) is a severe, potentially life-threatening infection of the renal parenchyma caused by gas-producing bacteria: Escherichia coli (66% of cases), Klebsiella (26%), and Proteus species.[17][18] The infection often develops suddenly and is seen almost exclusively in patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (over 90% of cases), and in those with papillary necrosis or upper urinary tract obstruction.[18] High levels of HbA1c and impaired host immune mechanisms are thought to predispose diabetic patients to EPN.[19]

Pathophysiology

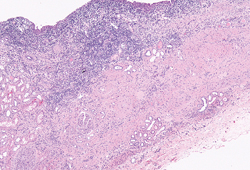

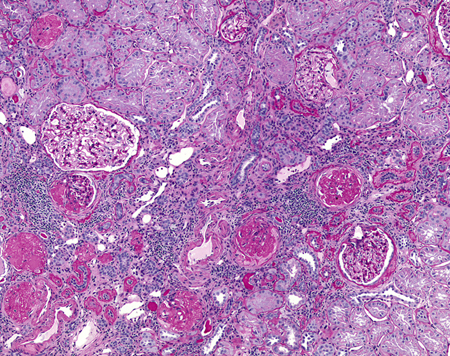

In most people, renal damage occurs slowly over a long period of time in response to a chronic inflammatory process or infections. This results in thinning of the renal cortex along with deep, segmental, coarse cortical scarring. Club-shaped deformity of the renal calyces occurs as the papilla(e) retract into the scar(s). One scar or several may be present, in one or both kidneys. Most scars develop in the upper and lower poles because of the frequency of reflux in these sites.[20] Parenchyma within the scarred areas often contains atrophic tubules with no glomeruli. Uninvolved tissue may be locally hypertrophied, with segmental involvement. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chronic pyelonephritis: tubular damage, interstitial scarring, and fibrosis in chronic pyelonephritisCourtesy of Jean L. Olson, MD, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, US [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Medium-power microscopic view of dense polymorphonuclear infiltrates, showing chronic tubular atrophy, glomerulosclerosis, and surrounding areas of normal tubules and glomeruliCourtesy of Jean L. Olson, MD, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, US [Citation ends].

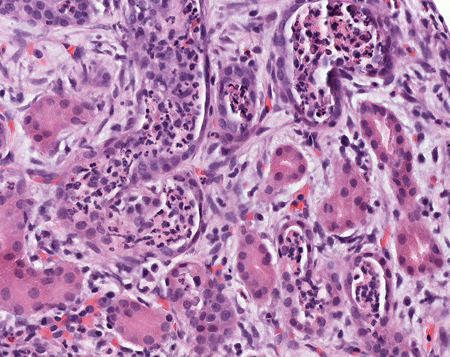

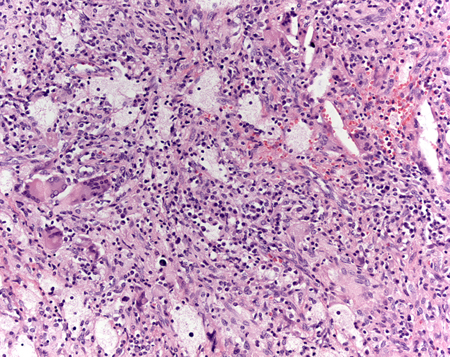

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Medium-power microscopic view of dense polymorphonuclear infiltrates, showing chronic tubular atrophy, glomerulosclerosis, and surrounding areas of normal tubules and glomeruliCourtesy of Jean L. Olson, MD, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, US [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: High-power view of polymorphonuclear cells in the renal tubules, showing damage to the tubules and red blood cell infiltration in the interstitial spacesCourtesy of Jean L. Olson, MD, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, US [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: High-power view of polymorphonuclear cells in the renal tubules, showing damage to the tubules and red blood cell infiltration in the interstitial spacesCourtesy of Jean L. Olson, MD, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, US [Citation ends].

Obstruction predisposes the kidney to infection, and chronic obstruction contributes to parenchymal atrophy. Obstruction can be bilateral (e.g., posterior urethral valves), resulting in renal insufficiency, or unilateral (e.g., calculi and unilateral anomalies of the ureter). Recurrent infections superimposed on diffuse or localized obstructive lesions lead to recurrent bouts of renal inflammation and scarring (the classic picture of chronic pyelonephritis).

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is the most common mechanism of renal scarring in chronic pyelonephritis.[21] Renal changes often begin early in childhood as a result of chronic urinary tract infection (UTI) superimposed on congenital VUR and intrarenal reflux. Reflux provides a direct route for infection to reach the kidney, and severe reflux may occur intrarenally. Scarring and atrophy lead to loss of tubular function, especially concentrating ability.[22][23] Most reflux-associated renal damage occurs in infancy, because with growth there is a tendency for self-correction of at least mild degrees of reflux.[11] Because of the lack of randomized clinical trials, clinical practice guidelines for screening neonates, infants, and the siblings of children with reflux are based on current practice and risk assessment.[24]

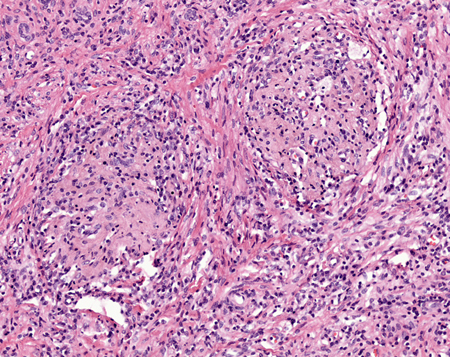

In xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, obstruction and infection lead to infiltration of monocytes and development of lipid-filled macrophages, the pathologic hallmark of the disease.[25][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: very low-power microscopic view showing extensive cellular infiltrate and granulomas. Note the marked destruction of the normal renal architectureCourtesy of Jean L. Olson, MD, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, US [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: H&E stain: high-power view of granulomas found in xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritisCourtesy of Jean L. Olson, MD, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, US [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: H&E stain: high-power view of granulomas found in xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritisCourtesy of Jean L. Olson, MD, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, US [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Very high-power view of xanthoma cells, which are lipid-filled macrophagesCourtesy of Jean L. Olson, MD, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, US [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Very high-power view of xanthoma cells, which are lipid-filled macrophagesCourtesy of Jean L. Olson, MD, Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, US [Citation ends].

In emphysematous pyelonephritis, the build-up of gas in the renal parenchyma can lead to a form of acute necrotizing pyelonephritis and sepsis that can be fatal if left untreated.[1] It is believed that the low oxygen tension allows an ascending UTI (mainly facultative anaerobes, such as E coli, Proteus, and Klebsiella species) to proliferate.[18]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer