Approach

The solitary pulmonary nodule is a common finding on chest x-ray and the widespread use of computed tomography (CT) has further increased the detection of this type of nodule.[10][11] The initial goal of the clinician is to distinguish the benign from the malignant lesion. If malignancy is strongly suspected then prompt resection of the lesion is indicated in most instances.

Clinical criteria and radiographic findings are used to determine the probability of malignancy and to make diagnostic and therapeutic decisions. No single approach applies to all patients.[12]

The most common differential diagnoses are infectious and inflammatory abnormalities, vasculitides such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis), primary lung cancer, and metastases to the lungs.

Clinical criteria for malignancy

Clinical features that are independent predictors of malignancy include older age, tobacco smoking status, and a history of previous cancer.

Older age

The probability of malignancy in a solitary pulmonary nodule is directly related to the patient's age. In order to quantify the influence of age on the probability of malignancy, the likelihood ratios can be calculated. The likelihood ratio is a ratio of the true positive fraction (sensitivity) to the false-positive fraction (1-specificity). A high likelihood ratio is useful for ruling in disease, a low likelihood ratio is useful for ruling out disease, and a likelihood ratio of 1 does not provide additional information about the likelihood of malignancy.[13] The likelihood ratio has been calculated as 0.05 for people <30 years old and 4.16 to 5.7 for those >70 years old.[14][15] A multivariate analysis has demonstrated age as an independent predictor of malignancy.[16]

Tobacco smoking status

Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for lung cancer and an independent predictor of malignancy in a solitary pulmonary nodule.[16] In a person who has never smoked, the likelihood ratio for malignancy in a solitary pulmonary nodule has been calculated to be 0.15 to 0.19.[14][15] This likelihood ratio increases as the number of cigarettes smoked increases (e.g., likelihood ratio 10-20 cigarettes a day = 1.0 and likelihood ratio >40 cigarettes a day = 3.9) and decreases with an increased duration of smoking abstinence (e.g., likelihood ratio <3 years' abstinence = 1.4 and likelihood ratio >13 years' abstinence = 0.1).

Cigar smoking is an independent risk factor for lung cancer. The relative risk for lung cancer in smokers of >5 cigars/day is 3.24 (CI 1.01 to 10.4).[17] Calculated likelihood ratios for malignancy in a solitary pulmonary nodule in a cigar smoker have ranged from 0.3 to 1.0. A cigar smoker with a solitary pulmonary nodule is, therefore, approximately 2 to 5 times as likely as a never-smoker (who has a likelihood ratio 0.15 to 0.19) to have a malignancy.[14][15] Calculated likelihood ratios, taken alone, do not constitute sufficient evidence to draw conclusions on the nature of a solitary pulmonary nodule.

Previous history of malignancy

A history of previous cancer (>5 years ago) is an independent predictor of malignancy in a solitary pulmonary nodule.[16] Likelihood ratios for malignancy in a patient known to have a previous malignancy ranged from 3.82 to 4.95, depending on the definition of prior malignancy.[14][16]

Consider other known risk factors for lung cancer

Presence of moderate or severe obstructive lung disease and exposure to fine particulate or sulfur oxide-related pollution are associated with lung cancer.[18][19] Other historical features, such as the presence of hemoptysis, have been used in clinical prediction models but have not been shown to be independent predictors of malignancy. The only combination of clinical features that could justify a clinician's decision to observe without further investigation is age <30 in a lifelong nonsmoker. All other clinical features are used to formulate a probability of cancer to direct further decisions. Guidelines recommend the use of validated risk models derived from screening studies to estimate risk.[20][21]

Radiographic criteria for malignancy

Several radiographic criteria are used to estimate the probability of malignancy in a solitary pulmonary nodule.

Pattern of calcification

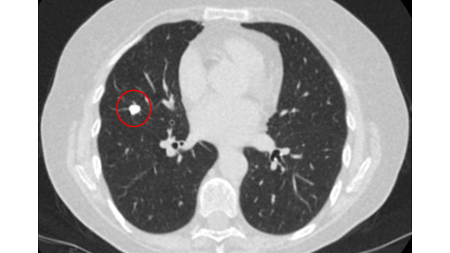

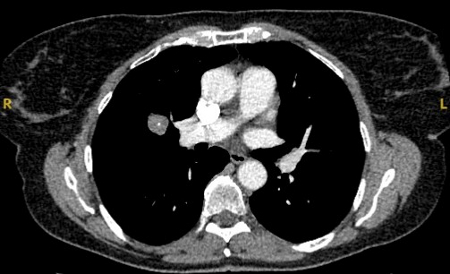

A dense central, laminated, chondroid pattern of calcification (often called popcorn calcification) or a diffuse pattern of calcification strongly suggests that a nodule is benign.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing a benign calcified granuloma in the right middle lobe, stable >10 years. The patient reported previous pneumonia on the same sideFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

A calculated likelihood ratio for malignancy with a benign pattern of calcification approaches zero.[14] Even so, approximately 13% of malignant nodules have a nonbenign pattern of calcification (see E and F).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A-D: calcification patterns of benign nodules; E, F: may be seen in malignant nodulesMazzone P.J., Stoller J.K. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;14:250-260; used with permission [Citation ends].

Growth rate

A very slowly growing solitary pulmonary nodule (volume doubling time >500 days) or, paradoxically, a very rapidly growing solitary pulmonary nodule (volume doubling time <30 days) suggests a benign etiology, although this is not an absolute rule. The traditional idea of 2 years of stability confirming benign disease is reasonable for solid solitary pulmonary nodules. However, it has been questioned and should be used cautiously in cases of ground-glass opacity.[22] The clinician should keep in mind that a 30% increase in diameter of a spherical lesion on x-ray represents a doubling of volume.

UK guidelines make the following recommendations regarding growth rate:[20][23]

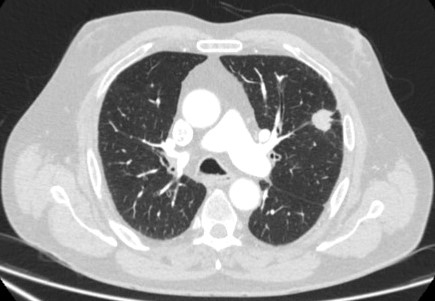

Solid nodules: volume doubling time of >600 days does not require follow-up, while a volume doubling time of <400 days, or clear growth defined as an increase in volume of 25% or more, suggests diagnostic investigations are required.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing a right upper lobe spiculated solitary nodule within emphysema, in a current smoker with previous asbestos exposure. Note the visible pleural plaque on the left side. Resection histology revealed adenocarcinoma of the lungFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

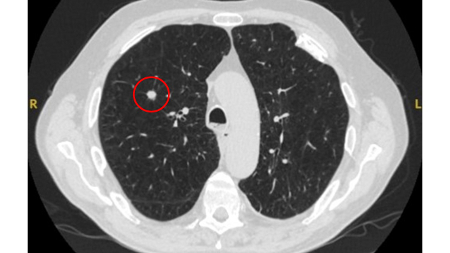

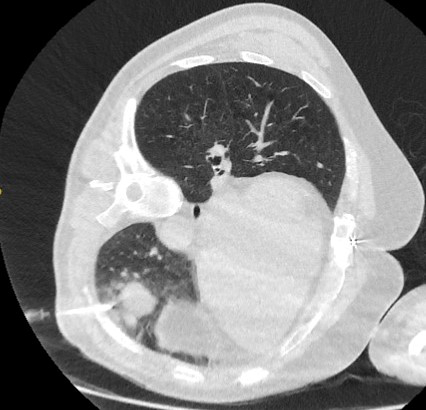

Ground-glass nodules: growth of 2 mm in maximum diameter should be considered potentially significant, while the development of a solid component suggests that further investigation and/or treatment should be considered.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing a left upper lobe ground-glass nodule. This was eventually resected 2 years into surveillance because of growth and the histopathology confirmed adenocarcinoma of lung with mixed mucinous-lepidic patternFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

Semi-solid nodules: growth of the solid component suggests that further investigation and/or treatment should be considered.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) sections with examples of semi-solid solitary nodulesFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

Edge characteristics

Benign nodules tend to have well-defined borders, while malignant nodules tend to be irregular or elongated. However, often a degree of overlap occurs and, taken alone, this feature cannot be reliably used as a discriminating factor.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing a small left upper lobe nodule with smooth margins, subsequently found to be a solitary colorectal metastasis on resectionFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

Size

Benign lesions tend to be smaller than malignant lesions. Prevalence of malignancy in nodules <5 mm is very low, between 0% and 1%.[24] UK guidelines suggest that nodules <5 mm do not routinely require follow-up or investigation.[20][24]

Location

Upper and middle lobe solitary pulmonary nodules have a likelihood ratio for malignancy of 1.2 to 1.6.[14][25] The upper lobe location has been shown to be an independent predictor of malignancy.[16]

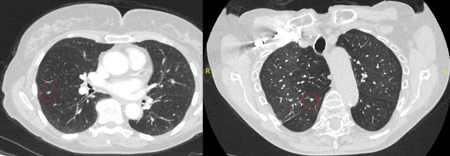

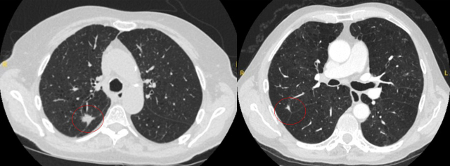

The appearance of the adjacent fissure, as well as any visible pleural "tags," are signs that need to be considered when evaluating perifissural or peripheral solitary lung nodules. A retracted fissure associated with a nonsmooth nodule increases the possibility of malignancy.[26][27][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) sections from two cases with benign perifissural nodules. Note the smooth margins and the normal undisturbed adjacent fissureFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing examples of malignant perifissural nodules. Note the spiculated edge of the nodules and the evident retraction of the adjacent fissure. Both resection tissue analyses confirmed adenocarcinoma of lungFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing examples of malignant perifissural nodules. Note the spiculated edge of the nodules and the evident retraction of the adjacent fissure. Both resection tissue analyses confirmed adenocarcinoma of lungFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing a left upper lobe spiculated nodule with a pleural ‘tag’. Resection histopathology confirmed a moderately-differentiated squamous cell lung cancerFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing a left upper lobe spiculated nodule with a pleural ‘tag’. Resection histopathology confirmed a moderately-differentiated squamous cell lung cancerFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing a left upper lobe peripheral nodule with several pleural ‘tags’ and element of retraction of the adjacent pleura. Resection histopathology confirmed a well-differentiated squamous cell lung cancerFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing a left upper lobe peripheral nodule with several pleural ‘tags’ and element of retraction of the adjacent pleura. Resection histopathology confirmed a well-differentiated squamous cell lung cancerFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

Diagnostic strategy

An appropriate workup for assessment of a solitary pulmonary nodule includes imaging studies and an assessment of the clinical likelihood of malignancy.[20][28] In the UK, respiratory physicians follow British Thoracic Society guidelines.[20]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Initial approach to solid pulmonary nodulesCallister MEJ et al. Thorax 2015;70:ii1-ii54; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Solid pulmonary nodule surveillance algorithm. VDT, volume doubling timeCallister MEJ et al. Thorax 2015;70:ii1-ii54; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Solid pulmonary nodule surveillance algorithm. VDT, volume doubling timeCallister MEJ et al. Thorax 2015;70:ii1-ii54; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sub-solid pulmonary nodules algorithm. PSNs, part solid nodules; SSN, sub-solid nodulesCallister MEJ et al. Thorax 2015;70:ii1-ii54; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sub-solid pulmonary nodules algorithm. PSNs, part solid nodules; SSN, sub-solid nodulesCallister MEJ et al. Thorax 2015;70:ii1-ii54; used with permission [Citation ends].

Comparison with prior chest x-ray or computed tomography (CT) scans

If the nodule has been present before and has not changed over a period of 2 years, observation is appropriate and no further workup may be indicated unless there is a high suspicion for a slow-growing malignancy (e.g., carcinoid, bronchoalveolar carcinoma).[5] The traditional idea of 2 years of stability confirming benign disease is reasonable for solid solitary pulmonary nodules. However, it has been questioned and should be used cautiously in cases of ground-glass opacity.[22]

Consideration of chest CT

If the lesion was detected on chest x-ray, chest CT should be performed. A high-resolution CT scan more accurately identifies characteristics of the nodule such as size, border, calcification, and location.[5] It can also identify other nodules and may help stage the disease if it proves to be malignant.

Assessment of the clinical likelihood of malignancy

Based on the historical characteristics (e.g., patient age, tobacco use, and presence of other malignancy) and the radiographic characteristics (e.g., calcification, growth rate, edge, and size), the clinician can estimate the likelihood of malignancy and then discuss with the patient the need for observation and noninvasive or invasive testing, according to the patient's wishes and overall health status.

Determination of probability of malignancy (pretest probability)

The pretest probability of malignancy, based on the clinical and radiographic features, allows the clinician to determine which patients can be safely observed, those who require excision, and those who are indeterminate.

In the UK and Canada, the Pan-Canadian Early Detection of Lung Cancer risk assessment model (PanCan model [also known as the Brock model]) is used to determine the probability of malignancy.[3] This model has been validated in UK and German populations.[2][29] The Herder model (that incorporates F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose [FDG] avidity) has been found to be more accurate in patients who undergo positron emission tomography (PET-CT) evaluation of pulmonary nodule.[29][30] UK guidelines, therefore, recommend that selected patients (pretest probability of malignancy >10% and solid component of a nodule greater than the local threshold size [usually 8 to 10 mm]) are evaluated by PET-CT and that the Herder model is used to determine risk thereafter.[20][31]

18F-FDG-PET/CT

One meta-analysis reported a sensitivity of 96.8% and a specificity of 77.8%.[32] This translates into a likelihood ratio for malignancy given a positive test of 4.36 and likelihood ratio for malignancy given a negative test of 0.04. False-positive results can occur in metabolically active benign nodules (e.g., infections); false-negative results can occur with relatively low metabolic activity tumors such as bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma or small (5 to 8 mm) tumors.[33]

PET-CT may underestimate the risk of malignancy in relation to pure ground-glass nodules, due to a lack of enough solid tissue to uptake the FDG.

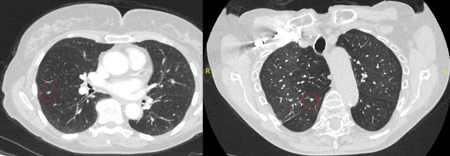

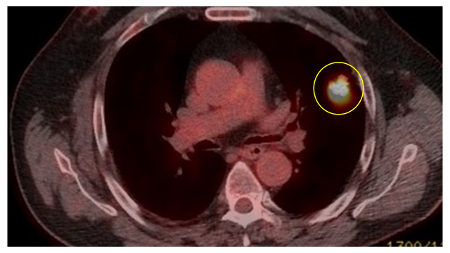

PET scanning can have a role in staging of tumors and has an especially high negative predictive value in excluding mediastinal involvement.[34][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) sections from two cases with benign perifissural nodules. Note the smooth margins and the normal undisturbed adjacent fissureFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: PET CT scan with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG) showing a low uptake in a semi-solid right upper lobe posterior lesion. Surgical resection confirmed adenocarcinoma with primarily lepidic patternFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

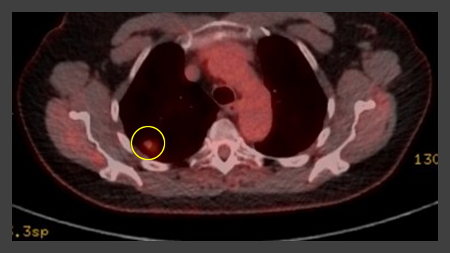

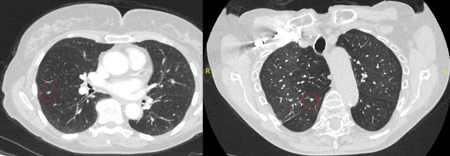

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: PET CT scan with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG) showing a low uptake in a semi-solid right upper lobe posterior lesion. Surgical resection confirmed adenocarcinoma with primarily lepidic patternFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: PET CT scan with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG) showing a high uptake peripheral left lung lesion. Surgical resection confirmed a moderately differentiated squamous cell lung cancerFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: PET CT scan with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG) showing a high uptake peripheral left lung lesion. Surgical resection confirmed a moderately differentiated squamous cell lung cancerFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

Serial CT scans and indications for further investigation during surveillance

If the initial probability of malignancy is <10%, UK guidelines recommend serial CT scans and observation.[20] Some patients with this level of risk may wish to proceed directly with a more invasive approach. Their wishes should be taken into consideration during the decision-making process.

Serial follow-up serves to:

reassure patients of nonmalignant pathology when nodules are stable, regress, or show very slow growth, or

allow definitive treatment of malignant pathologies in a timely manner.

CT surveillance is not recommended for patients who are not sufficiently fit to tolerate treatment.

Prior radiology should be reviewed to determine if the nodule has been imaged previously. The oldest (first) scan that fully captures the nodule is considered the baseline. Volumetry is the preferred method of measurement (diameter measurements, with extended duration of surveillance, when volumetry is not available). An increase in volume of 25% or more during serial scans should be considered as significant growth.[20]

Diagnostic and management strategies for a solitary pulmonary nodule: a general approach

The following represents the authors’ approach. Recommendations, however, vary across guidelines.[20][21][26][28][31] Surveillance periods can be determined retrospectively if previous imaging adequately captures the nodule of concern.

Solid nodules

Nodule under 5 mm maximum diameter or under 80 mm³ volume, or clear benign feature:

no follow-up recommended[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) sections from two cases with benign perifissural nodules. Note the smooth margins and the normal undisturbed adjacent fissureFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A-D: calcification patterns of benign nodules; E, F: may be seen in malignant nodulesMazzone P.J., Stoller J.K. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;14:250-260; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A-D: calcification patterns of benign nodules; E, F: may be seen in malignant nodulesMazzone P.J., Stoller J.K. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;14:250-260; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) section with soft tissue configuration, showing a right lung hamartoma, as incidental finding in an asymptomatic patient. Note the central calcification and several small spots of fat within the nodule. This nodule was stable over a 12 year period and no intervention requiredFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) section with soft tissue configuration, showing a right lung hamartoma, as incidental finding in an asymptomatic patient. Note the central calcification and several small spots of fat within the nodule. This nodule was stable over a 12 year period and no intervention requiredFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing a small peripheral triangular nodule in the right lower lobe, consistent with an intrapulmonary lymph nodeFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing a small peripheral triangular nodule in the right lower lobe, consistent with an intrapulmonary lymph nodeFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

Nodule ≥5 to <6 mm:

repeat CT at 1 year, and again at 2 years if based on 2D measurements alone

Nodule ≥6 to <8 mm in diameter or ≥80 to <300 mm³:

repeat CT at 3 months; if nodule stable/volume doubling time 400 days or more repeat again at 1 year (from baseline), and at 2 years if based on 2D measurements alone

Nodule ≥8 mm diameter or ≥300 mm³ volume, PanCan risk assessment model suggests <10% risk of malignancy:

follow-up as per ≥6 to <8 mm nodule

Nodule ≥8 mm diameter or ≥300 mm³ volume, PanCan risk assessment model suggests >10% risk of malignancy:

use PET-CT and update risk using Herder model

risk <10%, follow-up as per ≥6 to <8 mm nodule

risk 10% to 70%, consider image-guided biopsy as first line

risk >70%, consider definitive treatment first line

increase in nodule volume of 25% or more or volume doubling time is <400 days at any point during surveillance

consider further investigation and/or definitive management

the volume doubling time is 400 to 600 days at any point during surveillance

either biopsy or further surveillance is acceptable, depending on patient preference

the volume doubling time is greater than 600 days at the end of the surveillance period

can be considered for discharge or further follow-up, depending on patient preference

stability of the nodule at the end of the surveillance period

suggests discharge back to usual care (including any screening) is appropriate

Pure ground-glass nodules and semi-solid nodules

Nodule under 5 mm maximum diameter:

no follow-up recommended

≥5 mm nodules

follow-up at 3 months

if nodule resolves, no further follow-up

if nodule persists, determine risk using PanCan risk assessment model

if the nodule persists and risk of malignancy is approximately <10%

follow-up at 1 year, 2 years, and 4 years from baseline

if the nodule persists and risk of malignancy is approximately >10%

discuss image-guided biopsy/resection, or further follow-up

throughout follow-up

if there is significant growth of a solid component, or the development of a new solid component in a previously ground-glass nodule, favor definitive treatment

growth of a pure ground-glass nodule by ≥2 mm in maximum diameter should warrant consideration of treatment, or early (<6 months) follow-up

New incidental nodules discovered during surveillance (either because of a previous nodule or through a national screening program)

May warrant different management.[35] The authors’ approach includes the following recommendations:[36]

Nodule <4 mm maximum diameter or <30 mm³:

do not require surveillance (note lower threshold for surveillance recommended for new nodules)

Nodule ≥30 mm³ to <300 mm³

followed up at 3 and 12 months

Nodule ≥4 to <8 mm

if volumetry is not available, follow-up at 3, 12, and 24 months

Nodule ≥300 mm³ or ≥8 mm

PET/CT if appropriate, and/or invasive investigation via suspected lung cancer pathway

Invasive evaluation

The approach will vary depending on size and location of the nodule, local epidemiology, and available human and technological resources. Ideally, the investigative technique used should be chosen following a consult with a trained expert and/or a consensus from the multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT). Local expertise, and consideration of the risks and benefits of each procedure, will inform the approach for the individual patient.

Flexible bronchoscopy

Samples can be collected by washings, brushings, transbronchial biopsy, and transbronchial needle aspiration. The probability of success depends on the location and size of the nodule, and the presence of a bronchus leading directly to the lesion (bronchus sign), as well as local expertise and availability of fluoroscopy. The sensitivity of this technique is widely variable, but has been reported to be 40% to 70% for 20 to 30 mm nodules.[37][38][39] The primary advantage of bronchoscopy is the very low rate of complications when compared with other sampling techniques.

One meta-analysis reported a pooled diagnostic yield of 70% for guided bronchoscopy techniques, with an increasing yield as the lesion size increased.[40] The pooled pneumothorax rate was 1.5% in 39 studies including 3052 lung nodules.

Navigational bronchoscopy

Use of CT with airway reconstruction allows the estimation of distance to target to be calculated by specialized software during bronchoscopy. This technique improves the yield of flexible bronchoscopy to approximately 74% for lesions.[40]

Flexible bronchoscopy with peripheral endobronchial ultrasound (pEBUS)

Commonly referred to as radial EBUS miniprobe. Endobronchial ultrasound allows the operator to visualize structures at sites distal to the reach of the flexible bronchoscope. A 20 mHz probe with a diameter of 1.4 mm or 1.8 mm can be introduced with the corresponding guide sheath into the segment of interest after careful interpretation of the CT of the chest. Once the intended target is reached, the probe can be removed, leaving in place the guide sheath. At this time, the biopsy forceps, needles, or brush can be introduced and samples are obtained. Overall diagnostic yield of this technique is 34% to 84%.[39][41][42] Confounders that may affect diagnostic yield include presence of "bronchus sign" on CT, concentric view (higher yield), or eccentric view (lower yield).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) showing a posterior left upper lobe spiculated nodule, with ‘bronchus sign’ in a female non-smoker. Bronchoscopic forceps biopsy and brushing assisted by radial EBUS miniprobe localisation, confirmed a non-Hodgkin’s lymphomaFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

Transthoracic needle aspiration/biopsy

CT-guided transthoracic needle aspiration (TTNA) sensitivity varies from 72% to 99%, but 90% is accepted as the average yield.[38] Determination of benign disease is more difficult due to the small amount of tissue collected by this method.[43] The most common complication associated with TTNA is pneumothorax, which occurs in around 20% to 45% of cases.[5][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Computed tomography (CT) section capturing the transthoracic core biopsy needle targeting a left lower lobe lobulated nodule. Histopathology confirmed a well-differentiated squamous cell lung cancerFrom the collection of Dr George Tsaknis, MD, PhD, FRCP(London), MRQA, MAcadMEd, PGCert; used with permission [Citation ends].

The relative frequency of pneumothorax, and other technical difficulties associated with TTNA, mean that bronchoscopy is often the preferred choice. TTNA may be reserved for cases where bronchoscopy is negative but continued investigation is warranted.

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or open surgical resection

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) or open surgical resection is indicated for the diagnosis and potential treatment of a solitary pulmonary nodule that remains undiagnosed by the above techniques, yet remains a concern.

Data from one randomized controlled trial comparing open lobectomy with VATS for early lung cancer (including solitary nodules) suggested that VATS was associated with less pain, fewer in-hospital complications, and shorter hospital stay.[44] VATS was associated with superior functional recovery in the postoperative period, without any difference in progression-free survival up to 1 year.

When discussing the surgical options with patients, it is important to consider that lobectomy is associated with an operative mortality of 3% to 7%, while wedge or nodule resection has a mortality of 0.5% to 1%.[25][45][46] Whenever the surgical biopsy of a solitary lung nodule confirms the presence of non-small cell lung cancer, a lobectomy with systematic mediastinal lymph node dissection is the treatment of choice. It is important to remember that a surgical approach demands an assessment of cardiopulmonary fitness prior to resection.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer