Approach

The systemic vasculitides are subacute illnesses associated with signs and symptoms of inflammation. Vasculitis can affect virtually any organ system; many of these diseases have typical patterns of involvement.

History and examination

The systemic vasculitides are subacute, and most patients will present with complaints of arthralgias, myalgias, fever, or malaise for several months before more specific signs or symptoms develop. Examination should focus on the identification of specific organ involvement, which may demonstrate a pattern of disease that could lead to a diagnosis.

Presence of headache and scalp tenderness is an alert to consider giant cell vasculitis. There may be vision changes, such as amaurosis fugax (often described as like a curtain dropping over the eye), or other painless visual symptoms (such as diplopia). Vision loss due to giant cell arteritis is generally permanent.

Arm claudication, which manifests as arm pain with repetitive motion, may be an indication of Takayasu arteritis or giant cell arteritis.

Digital loss in the hands or feet is particularly characteristic of thromboangiitis obliterans, although this may also be seen with polyarteritis nodosa and rheumatoid vasculitis.

The most common cause of the pulmonary-renal syndromes are the antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides, which include granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis is associated with chronic sinusitis, nasal discharge and crusting, epistaxis, nasal ulcers, nasal septal perforation, saddle nose deformity, otorrhea, ear pain or muffled sensation in the ears, and hemoptysis.

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis is associated with refractory asthma, nasal polyps and sinus disease.

In general, features of large-vessel vasculitis include upper extremity or jaw claudication, asymmetric brachial pulses, vascular bruits, or visual changes. Features of medium-vessel vasculitides include abdominal pain, foot/wrist drop, or cutaneous ulcers. Features of small-vessel vasculitides include hematuria, hemoptysis, or palpable purpura. More generalized symptoms such as arthralgia, fevers and weight loss can be seen in all types of vasculitis.

Laboratory tests

No blood test is specific for a diagnosis of systemic vasculitis.

Inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein) should be ordered in all patients in the initial workup and are generally elevated in a patient with a new diagnosis of systemic vasculitis.

A specific laboratory test that can be sent in the initial workup is ANCA. A positive result is strongly correlated with ANCA-associated vasculitis (i.e., granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis). See Granulomatosis with polyangiitis and Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Small-vessel vasculitis can involve the kidneys, leading to glomerulonephritis. Assessment for glomerulonephritis involves additional tests such as urinalysis, microscopy of urine sediment, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). See Glomerulonephritis for the full diagnostic work-up.

Pathology

The decision to conduct a biopsy should be made on clinical grounds, with the site of affected organs taken into consideration with the associated risk of the procedure (e.g., skin lesions are more amenable to biopsy than the aortic arch is). The value of a biopsy of an involved organ, performed early in the disease course, cannot be overestimated. However, if the patient has a history of chronic immunosuppression the results may be misleading.

The unifying feature of systemic vasculitis is the presence of immune-mediated blood vessel wall injury. Fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall with karyorrhexis (fragmentation of the nucleus and the breakup of the chromatin into unstructured granules) and red blood cell extravasation are pathognomonic for this disorder.[7] Note that a perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrate is not diagnostic of vasculitis and may be seen in other inflammatory conditions.

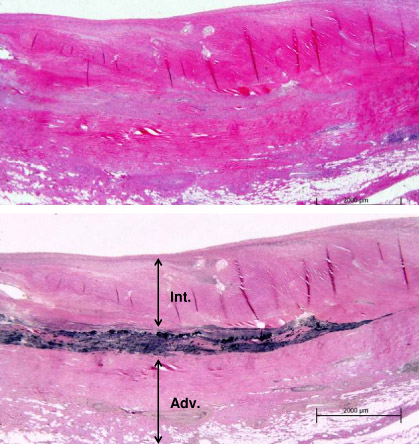

Direct immunofluorescence should be performed on the biopsied tissue whenever possible, as the pattern of immunoglobulin deposition may provide additional clues to the underlying etiology. Immunoglobulin (Ig) M and C3 deposition are consistent with a mixed-essential cryoglobulinemia. IgA deposition is seen in IgA vasculitis. The presence of a pauci-immune vasculitis with minimal immunoreactants on immunofluorescence is consistent with an ANCA-associated vasculitis such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Biopsy specimen showing florid transmural inflammation of a small arteryFrom the collection of Loic Guillevin, MD, Hopital Cochin, Paris, France [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Photomicrograph of the aorta from a patient with Takayasu arteritis demonstrating marked thickening of the intimal layer and inflammatory infiltrates in the media and laminar necrosisFrom the collection of Dylan Miller, MD, Mayo Clinic [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Photomicrograph of the aorta from a patient with Takayasu arteritis demonstrating marked thickening of the intimal layer and inflammatory infiltrates in the media and laminar necrosisFrom the collection of Dylan Miller, MD, Mayo Clinic [Citation ends].

Imaging

Conventional angiography can be useful to establish a diagnosis of medium- or large-vessel vasculitis and is often particularly useful in suspected polyarteritis nodosa, Takayasu arteritis, and giant cell arteritis with an aortic arch syndrome.

Magnetic resonance imaging and angiography (MRA) can be equally good for the evaluation of large-vessel vasculitis, but generally MRA lacks the resolution to establish the presence of smaller vessel involvement. The utility of positron emission tomography scanning has not been well established, although it may be useful to help establish the diagnosis of the large-vessel vasculitides, such as giant cell arteritis or Takayasu arteritis.[8] See Polyarteritis nodosa, Takayasu arteritis, and Giant cell arteritis.

However, in practice, it should be noted that there is no imaging finding that is entirely specific for vasculitis as opposed to other vascular pathologies such as vasospasm, atherosclerosis, etc. Therefore imaging alone does not establish the diagnosis as vascular abnormalities can be incidentally identified on imaging studies performed on asymptomatic patients.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer