Approach

Around 90% of vaginitis is caused by infection, mainly bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), and trichomoniasis.[11] These three diagnoses should be excluded in all patients before considering other less common causes.

Clinical history and examination

In a patient presenting with vaginal discharge, the initial history should include:

Any new sexual partners

Number of partners in the past year

Use of new soaps or detergents

Use of feminine hygiene products (e.g., douches, wipes, sprays)

Contraceptive use, including vaginal ring or intrauterine device

Previous therapies

Urinary tract symptoms (e.g., frequency, urgency, dysuria)

Symptoms such as pelvic pain, itching, quality/quantity/odor of discharge

Bacterial vaginosis typically presents with a thin discharge and fishy odor ("whiff test"). Trichomoniasis presents with a purulent malodorous discharge. VVC presents with a white, cottage cheese discharge and pruritus.

A physical examination should include visualization of the vulva, vagina, and cervix in search of lesions and/or erythema, and a bimanual examination to evaluate for pelvic mass or cervical motion tenderness.

In symptomatic women, self-obtained vaginal swabs and history alone may not be as useful as physical assessment and speculum exam by a clinician.[70] Self-obtained swabs are a valid alternative to clinician-obtained swabs, and should be offered if examination is declined.[71][72][73][74][75][76]

Routine investigation

A sample of vaginal discharge should be obtained and pH elucidated using litmus paper.[38] Wet mount microscopy is performed by placing a small sample of discharge on 2 separate areas in a slide and adding normal saline to 1 area and potassium hydroxide to the second. A cover slip is then placed on the slide, which is then visualized with a microscope. The patient should be counseled and treated appropriately if the wet mount confirms any of the following findings.[9][38]

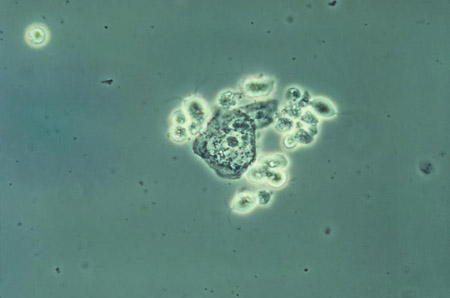

Amsel criteria, 3 out of 4 of: thin, homogeneous discharge; vaginal pH >4.5; a positive whiff test or release of amine odor with the addition of base (10% potassium hydroxide); clue cells on microscopic evaluation of saline wet preparation (bacterial vaginosis). [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Photomicrograph revealing bacteria adhering to vaginal epithelial cells, known as clue cellsCDC Image Library; M. Rein [Citation ends].

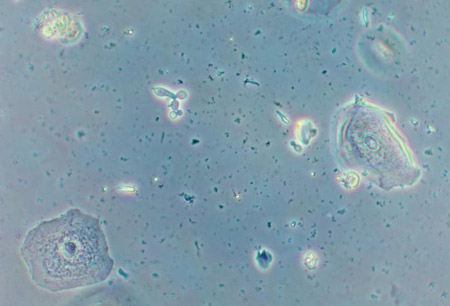

Trichomonads (44% to 68% sensitive for trichomoniasis). [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Phase contrast wet mount micrograph of a vaginal discharge revealing the presence of Trichomonas vaginalis protozoa CDC Image Library [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Trichomonasvaginitis with copious purulent discharge emanating from the cervical os CDC Image Library [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Trichomonasvaginitis with copious purulent discharge emanating from the cervical os CDC Image Library [Citation ends].

Budding yeast and hyphae (candidiasis). [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vaginal smear identifying Candida albicans using Gram stain technique CDC Image Library; Dr Stuart Brown [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vaginal smear identifying Candida albicans using a wet mount technique CDC Image Library; Dr Stuart Brown [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vaginal smear identifying Candida albicans using a wet mount technique CDC Image Library; Dr Stuart Brown [Citation ends].

White blood cells without trichomonads or yeast (may suggest cervicitis).

Alternative or supplementary tests include the following:

Fungal culture with sensitivities for VVC: should be obtained to confirm diagnosis in patients with typical clinical features but normal vaginal pH and negative wet mount microscopy. Should also be obtained for patients with recurrent symptoms and multiple failed therapies.

Vaginal assays for trichomoniasis: should be considered if pH is >4.5, if there are high polymorphonuclear leukocytes but no motile trichomonads on wet mount microscopy, or if microscopy is not available.

Gram stain to determine the relative concentration of lactobacilli: considered by some to be the best test for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis.[9] Quantitative gram stain is specific for bacterial vaginosis, but 20% to 30% indeterminate.[77] A Gram stain can be evaluated by the Nugent criteria or the Hay-Ison criteria. The Nugent criteria report the relative proportions of the different bacterial morphotypes. The Hay-Ison criteria are graded: 0 for only epithelial cells; 1 for mostly Lactobacillus; 2 for mixed flora; 3 for predominantly Gardnerella and/or Mobiluncus; and 4 for aerobic vaginitis with mostly aerobic bacteria. The British Association for Sexual Health and HIV recommends using the Hay-Ison criteria over the Nugent criteria.[25]

Multiple studies have demonstrated, that multiplex vaginal panels more accurately diagnose bacterial vaginosis, VVC and TV better than current standard of care investigations.[77] Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs, which include polymerase chain reaction [PCR] assays) are available for the detection of Candida, trichomoniasis, herpes simplex virus, mycoplasma, chlamydia, gonorrhea, and organisms commonly associated with bacterial vaginosis.[77] NAATs are more accurate than a nucleic acid probe, but are expensive.[78] Traditional tests may remain useful for the diagnosis of these infections because of their lower cost and ability of some to provide a rapid diagnosis.[9][77][78]

Women at risk for sexually transmitted infections

In women at risk for sexually transmitted infections (those with new, multiple partners, or partners who have multiple partners, and women younger than 25 years old) and with profuse yellowish vaginal discharge, a pelvic examination should be performed and assays for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis obtained.

Mycoplasma genitalium testing may be considered in symptomatic women with recurrent cervicitis or who are on-going sexual contacts of persons being treated for M genitalium infection.[9][51][79] Women with vaginal discharge should also be tested for Trichomonas vaginalis.[9]

If the discharge is accompanied by pelvic pain and/or cervical motion tenderness, the patient should be treated for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) according to Centers for Disease Control guidelines.[9] Treatment of N gonorrhoeae, C trachomatis,and suspected PID aims to prevent ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and chronic pelvic pain.

Recurrent vaginal discharge

If the patient presents with recurrent vaginal discharge, other diagnoses should be considered, including recurrent VVC.

Patients with recurrent VVC (usually defined as three or more episodes of symptomatic VVC in less than 1 year) should have the following excluded: diabetes mellitus; immunocompromised states such as HIV and other types of Candida (e.g., Candida glabrata), as they can be resistant to antifungal agents used in the management of Candida albicans.[9]

Normal examination and negative results

Patients with vaginal discharge, an unremarkable examination, negative assays, and a history concordant with possible irritants (e.g., change in soap or detergents) have allergic vaginitis. This typically resolves with avoidance of the irritant.

Poor hygiene must be considered in those with negative assays and no history of contact irritants: for example, patients who don't change tampons regularly or who clean inappropriately (wiping back to front).

Patients with isolated vaginal discharge of normal color, odor, and consistency, and who have a normal pelvic examination and wet mount, can be reassured that the vaginal discharge is of the physiologic type.

Uncommon causes

Other causes of vaginal discharge should be ruled out by appropriate tests and studies once more common causes have been excluded clinically and/or by investigation.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM)

If the woman is postmenopausal and the vaginal epithelium appears pale, smooth, and shiny with loss of rugae, then clinical diagnosis of GSM may be considered.[14][80]

Vaginal discharge may be white, yellow, or malodorous.

Microscopy reveals abundant white blood cells, parabasal cells, and absent infectious pathogens. The vaginal maturation index can be used to test the efficacy of therapies, but it is predominantly used in research studies.[14]

Physiologic postpuerperal atrophic vaginitis

History of recent child birth with characteristic discharge is diagnostic.

Herpes simplex virus

Multiple crops of painful, shallow ulcers may indicate herpes simplex virus cervicitis and can be confirmed with viral cultures, nucleic acid assays, and type-specific serologic tests.

Foreign body

Presents with malodorous discharge and irritation, and if longstanding can lead to extensive adhesion formation with near complete obstruction of the vagina inferior to the location of the foreign body.[68]

Diagnosis may be confirmed with a pelvic examination, pelvic x-ray, transvaginal/transabdominal ultrasound, and/or contrast pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Behcet syndrome

Will present with other features of the syndrome (e.g., aphthous ulcers, skin lesions, and uveitis) in addition to vaginal ulceration and discharge. Typically diagnosed clinically.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

Associated with purulent and copious discharge, severe dyspareunia, or minor vulvar symptoms such as irritation and/or pruritus; may indicate diagnosis of inflammatory vaginitis.

Vagina may show signs of inflammation (e.g., erythema, linear erosions).

Wet mount excludes infectious cause and shows an abundance of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Parabasal cells are often found.

Vaginal pH >4.5.

Lichen planus

May be difficult to distinguish from GSM if there are no extravaginal symptoms.

Presents with shiny papules, which are typically intensely itchy. Biopsy confirms diagnosis.

Streptococcal vaginitis in adults

Predisposing factors include household or personal history of an upper respiratory tract infection with group A streptococci, sexual contact, or vaginal atrophy. Vaginal discharge is profuse or copious. Diagnosis is confirmed with culture.[53]

Genital schistosomiasis

Has been described in Africa; may be encountered in the West subsequent to increased tourism.[81] Characterized by copious vaginal discharge and an erythematous cervix. Diagnosis is made by microscopic detection of parasitic eggs in urine, followed by cervical punch biopsy.[54] Punch biopsy has 100% sensitivity for schistosomiasis but can increase HIV transmission due to breakdown of the mucosal barrier, therefore the risk and benefits of punch biopsy need to be carefully weighed. High-magnification colposcopy may also be used for diagnosis.[82]

Entamoeba gingivalis

Postsurgical

Prior history of intravaginal slingplasty with onset of purulent and offensive vaginal discharge suggests postsurgical (rare) vaginitis and can be confirmed with contrast MRI. In April 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prohibited sales and distribution of surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of anterior compartment prolapse (cystocele).[60] In October 2022, the FDA published a statement maintaining that these devices do not have a favorable benefit-risk profile.[61]

Postradiation

History of radiation therapy; radiation therapy changes may be present.[57]

Prolapsing fibroid

Less common cause of vaginal discharge reported in the literature.[83]

Vaginal fistula

Less common cause of vaginal discharge reported in the literature.[84]

Graft versus host disease

Should be considered in women with a history of a transplant. Symptoms include vaginal dryness, burning, or itching. If left untreated, it can lead to severe vaginal scarring.[85][86]

Genital tract cancer

Should always be considered in women presenting with a persistent vaginal discharge, particularly if blood stained.

Cervical cancer: an older patient presenting with foul-smelling discharge and a cervical mass on examination should have a biopsy of the mass, and consideration of a Pap smear and CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis to rule out cervical cancer.

Carcinoma of the fallopian tube: rare, and only 16% of patients present with the classic triad of vaginal discharge, colicky pelvic pain, and palpable pelvic mass, although data are very limited.[87] Pelvic ultrasound and CA-125 may aid diagnosis, but surgical staging is definitive.

Pediatric patients

In the pediatric population, foreign body and sexual abuse should always be ruled out clinically and, if necessary, by history and physical exam, vaginal swabs, transabdominal pelvic ultrasound, vaginoscopy, and referral to a child abuse specialist.

Other diagnoses and investigations include the following.

Microscopy of vaginal sample demonstrates sheets of vaginal epithelium in physiologic discharge.

Recent history of pharyngitis and signs of vaginal infection suggest streptococcal vaginitis, which is confirmed with vaginal swabs for streptococcal organisms.

Infants (age <1 year) with vaginal symptoms may have been infected by the mother in the birth canal. Vaginal and cervical swabs of the mother confirm this.

If there is a history of use of bubble baths, perfumed soaps, tight-fitting clothes, or back-to-front wiping then diagnosis of nonspecific vaginitis is clinical.

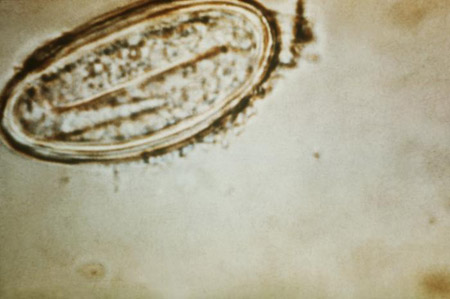

Pinworms may be suspected if there is nocturnal discomfort or pruritus. Cellophane tape testing or direct visualization confirms the diagnosis. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Enterobius vermicularis egg (human pinworm) CDC Image Library [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer