Approach

Diagnosis requires a thorough history from the patient and, if at all possible, from family members and friends. Treatment is most successful if anorexia nervosa (AN) is detected early; however, this is often difficult to do.[64][65] Detection of eating disorders in their early stages, when psychological and physical symptoms are subtle, can be challenging for primary care physicians.

According to US guidance the initial evaluation of a person with a possible eating disorder should include assessment of multiple factors, including but not limited to:[66]

The person’s height and weight history

Their history of eating-related behaviors; for example, restrictive eating, food avoidance, patterns, and changes in food repertoire

Their history of compensatory behaviors; for example, exercise, purging behaviors (including laxative use, self-induced vomiting)

The percentage of time preoccupied with food, weight, and body shape

Any prior treatment and response to treatment for an eating disorder

Any family history of eating disorders, other psychiatric illnesses, and medical conditions

In any group, cases may remain undetected if clinicians omit specific questions about eating, weight history, and associated cognitions. Additionally, patients may not reveal symptoms of illness. If clinicians suspect AN, risk assessment to assess impending risk to life is key; be aware that people may appear deceptively well even in the presence of severe AN. Normal blood tests results and relatively preserved energy levels should not be taken as cause for reassurance.[67]

Clinical history

People with AN may be deeply ashamed of their disordered eating.[67] They will often minimize or frankly deny the presence of their extreme dieting and other illness-related behavior. Patients are unlikely to seek care for AN, per se, but may complain of related symptoms such as amenorrhea, fatigue, and dizziness.[67] Collateral history from family members, friends, and primary care records is therefore essential. Family members may have identified and become concerned about the patient's weight loss and other associated symptoms. In either case, upon interview, a resistance to gaining weight and a distortion of body image may be apparent. The patient may fixate on specific overweight areas of the body but recognize an overall slimness or may completely deny that he or she is underweight.

The initial psychiatric evaluation should aim to quantify eating and weight control behaviors (e.g., frequency, intensity, or time spent on dietary restriction, binge eating, purging, exercise, and other compensatory behaviors). This is useful as part of the initial assessment to determine severity of eating disorder behaviors and associated symptoms, and may include the use of formal rating scales.[66] Dietary habits should be assessed in some detail. Some individuals with AN follow vegetarian or more restrictive vegan diets. It is helpful to determine if the onset of AN coincides with a vegetarian or vegan diet. If so, this choice may be part of the disorder and it may be appropriate to discourage the patient from following this dietary choice. If the vegetarian or vegan diet clearly began prior to onset of AN, assisting the patient to follow this diet may be possible, but with critical attention to the need to ensure adequate caloric intake.

On interview, the diagnostic subtype, restricting or binge-eating/purging, should be identified. Individuals with the restricting subtype rigorously diet and may also focus upon burning calories through exercise. Individuals with the binge-eating/purging subtype restrict calories, but also engage in binge-eating and/or purging behavior. Individuals with the binge-eating/purging subtype are also more likely to misuse laxatives, diuretics, and enemas.

The interviewer should also assess commonly co-occurring psychiatric conditions, which is important for treatment planning, given that comorbid psychiatric conditions require treatment and are associated with worse outcomes and greater mortality.[66] Obsessive compulsive disorder is frequent among individuals with AN, and the lifetime risk of substance use disorders may be as high as 50%.[68] Depression and dysthymia are also common comorbid psychiatric disorders. A careful assessment of suicide risk is important.[66] Suicidal ideation is common; 20% of deaths amongst adults with AN are attributable to suicide.[69] In children and adolescents, an assessment of suicidality is recommended as part of a fuller psychosocial assessment; a home, education, activities, drugs/diet, sexuality, suicidality/depression (HEADSS) assessment is recommended according to US guidance.[70]

Evaluation of medical comorbidity is important, including conditions which may increase mortality and affect treatment (e.g., diabetes mellitus) and those which may put a person at increased risk of disordered eating and/or suggest the presence of an alternative diagnosis (e.g., celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease).[66]

In prepubertal patients with sudden onset AN arising shortly after an apparent streptococcal infection, pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS) should be considered.[71]

Menstrual functioning should be assessed because amenorrhea is common in girls and women with AN.[66] Note whether the patient is taking oral contraceptives, as regular uterine bleeding due to contraceptive-induced effects may mask hypogonadism and lead a patient to believe her reproductive system is functioning normally.

Physical exam

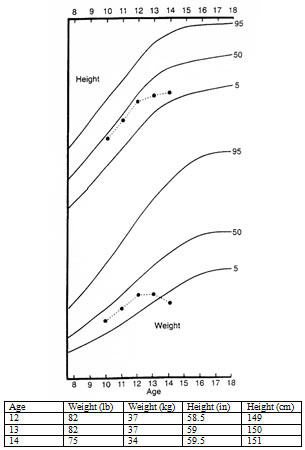

In the early stages of illness, physical exam and laboratory tests are often normal; later, however, physical signs and results of laboratory testing may be useful in determining severity and any impending risk to life.[72] Weight should be recorded and height should be measured.[66] If the patient weighs significantly below normal for his or her age and height, or a high suspicion for illness exists, then weekly appointments should be scheduled to record symptoms and weights. Additionally, a body mass index (BMI) of <17.5 kg/m² in an adult or below the 5th percentile on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) BMI-for-age calculator for children and adolescents should be of significant concern.[73] It should be noted that, in addition to using the CDC BMI-for-age calculator, the clinician should determine whether the patient is still on his or her own growth curve.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Height and weight of a girl between the ages of 10 and 14.5 years, charted against age percentiles. She fell ill at 12 years of age and began losing weight. She was not diagnosed until 2 years later, at the age of 14. The weight loss was difficult to recognize by the physician as the patient did not gain in height over the 2-year period.From the personal collection of Pauline S. Powers [Citation ends]. [

Body Mass Index (BMI) percentiles for boys (2 to 20 years)

Opens in new window

]

[

Body Mass Index (BMI) percentiles for girls (2 to 20 years)

Opens in new window

]

[

Body Mass Index (BMI) percentiles for boys (2 to 20 years)

Opens in new window

]

[

Body Mass Index (BMI) percentiles for girls (2 to 20 years)

Opens in new window

]

A BMI of <13 kg/m² in an adult, and BMI less than 70% of the predicted BMI for age in a child, indicates an impending risk to life. Note that the rate of weight loss is also important; loss of >1 kg per week for 2 consecutive weeks indicates particular cause for concern.[67]

The physical exam should pay particular attention to vital signs, given that abnormalities may indicate medical instability warranting a higher level of care.[66]

The following set of observations are recommended according to US guidance:[66]

Temperature

Resting heart rate

Blood pressure

Orthostatic pulse

Orthostatic blood pressure

Vital signs may be notable for low temperature, and reduced heart rate and blood pressure. Core temperature of <96°F and heart rate of less than 40 are both markers of high impending risk to life.[67] Orthostatic hypotension may be noted, especially among affected adolescents; postural hypotension with recurrent syncope is another particular cause for concern and is typically seen in conjunction with echocardiogram abnormalities for as long as malnutrition persists.[67]

Observe patient for signs of malnutrition, and look for evidence of purging behaviors.[66] Fat mass distribution may be observably low with accompanying protruding bony structures, such as the scapula. Some patients develop fine body hair referred to as lanugo on their trunk, extremities, or face. On oral exam, patients who engage in frequent vomiting may display erosion of tooth enamel, and swollen salivary glands.

Laboratory tests

Recommended laboratory tests include:[66][70]

Complete blood count (CBC)

Serum chemistry (electrolyte) panel

Thyroid function tests

Liver function tests

Blood glucose

Urinalysis

Laboratory results are not necessary for the diagnostic assessment, but are useful in the assessment of illness severity and recommendation for the appropriate treatment setting (e.g., hospital or other structured treatment program versus outpatient treatment).

CBC may show leukopenia and possibly other low cell counts; serum chemistry may show hypokalemia, hypochloremia, abnormal serum bicarbonate levels, or elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels, especially in those patients consistently purging by vomiting or laxative misuse. Hyponatremia may be present in individuals who drink large amounts of water as part of their illness symptoms.

When present, hypophosphatemia is particularly worrisome and may indicate vulnerability to, or the presence of "refeeding syndrome", a dangerous state of nutrient deficiency, cognitive function change, and congestive heart failure. Elevated BUN levels may indicate dehydration or can be an indication of renal function abnormalities. Elevated serum amylase may be present in individuals who purge by vomiting.

A urinalysis may be useful to assess hydration status; also, ketonuria, indicative of semi-starvation, may be present acutely.

Hypoglycemia (glucose <59.46 mg/DL [3 mmol/L]) also indicates starvation, often in conjunction with raised ketones, and indicates significant cause for concern; if present, check for additional diagnoses (e.g., sepsis) or alternative diagnoses (e.g., Addison disease, insulin misuse).[67]

Most laboratory abnormalities improve with supervised refeeding and weight restoration. More significant abnormalities, such as hypophosphatemia or severe hypokalemia are potentially life-threatening and may require specific nutrient supplementation.[67]

Laboratory assessments should be repeated in those patients who are inpatients to monitor progress and severity of disease. Outpatients may also need periodic laboratory assessment. In individuals with menstrual irregularity or interruption, consider measuring hormone levels (e.g., estrogen, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, and thyroid-stimulating hormone, as well as a urine or serum pregnancy test) to exclude other causes of amenorrhea.[66] In males, consider measuring testosterone levels. UK guidance recommends consideration a bone mineral density scan after 1 year of underweight in children and young people (earlier if they have recurrent bone pain or fractures) and after 2 years of underweight in adults (earlier if they have bone pain or recurrent fractures).[65] According to US guidance, clinicians should consider bone densitometry for children and adolescents with amenorrhea for more than 6-12 months.[66][70]

Subsequent tests to consider include an ECG; this is recommended in all patients with a restrictive eating disorder, patients with severe purging behavior, and patients who are taking medications that are known to prolong QTc intervals.[65][66]

An ECG may be ordered initially if the patient is severely ill requiring hospitalization (e.g., suspected electrolyte disturbance, severe malnutrition, severe dehydration, or signs of incipient organ failure).[65] High risk features on ECG include prolonged QTc (<18 years: males >450 ms, females >460 ms; ≥18 years: males >430 ms, females >450 ms), heart rate <40 bpm, and arrhythmia associated with malnutrition and/or electrolyte disturbances.[67]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer