Etiology

The cause of UC is unclear, but it seems to occur in genetically susceptible people in response to environmental triggers. Epidemiological studies have highlighted genetic predisposition factors for inflammatory bowel disease; among patients with UC, 10% to 20% will have a family history of inflammatory bowel disease.[12][13] In a population-based study, the risk of UC was increased in first-degree relatives (incident rate ratio [IRR] 4.08), second-degree relatives (IRR 1.85), and third-degree relatives (IRR 1.51) of patients with UC.[14] Nonetheless, genome-wide association studies estimate that <13% of disease heritability is explained by genetic variation, indicating that environmental/epigenetic factors contribute.[15][16]

UC is probably an autoimmune disease initiated by an inflammatory response to colonic bacteria. Immune dysfunction has been postulated as a cause, with limited evidence. UC might also be linked to diet, although diet is thought to play a secondary role. Food or bacterial antigens might affect the already damaged mucosal lining, which has increased permeability.[17][18]

Pathophysiology

Macroscopically, most cases of UC arise in the rectum, with some patients developing terminal ileitis (i.e., extending up to 30 cm) due to an incompetent ileocecal valve or backwash ileitis. The bowel wall is thin or of normal thickness, but the presence of edema, the accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give the impression of a thickened bowel wall. The term "proctitis" is used when the inflammation is limited to the rectum.

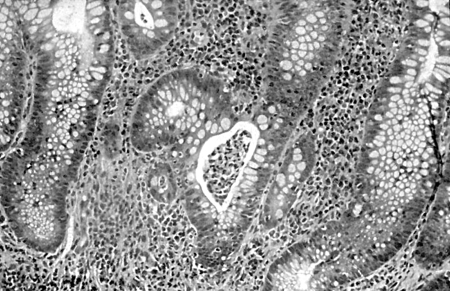

Microscopically, UC usually involves only the mucosa, with the formation of crypt abscesses and a coexisting depletion of goblet cell mucin. In severe cases, the submucosa can be involved, and in some cases, the deeper muscular layers of the colonic wall can also be affected. Further microscopic changes include inflammation of the crypts of Lieberkuhn and abscesses. Ulcerated areas are soon covered by granulation tissue. The undermining of mucosa and the excesses of granulation tissue form polypoidal mucosal excrescences, known as inflammatory polyps or pseudopolyps.[1][2][3][18][19][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colonic biopsy specimen showing severe mucosal inflammation, formation of crypt abscess, mild glandular atrophy, and distortion, suggesting an active phase of ulcerative colitis; hematoxylin/eosin staining, ×400 magnificationFrom Iannone F, Scioscia C, Musio A, et al Leucocytoclastic vasculitis as onset symptom of ulcerative colitis Ann Rheum Dis 2003 Aug;62(8):785-6; used with permission [Citation ends].

Early disease manifests as bleeding, petechial hemorrhages, and hemorrhagic inflammation with loss of the normal vascular pattern. Edema is present, and large areas become denuded of mucosa. Undermining of the mucosa leads to the formation of crypt abscesses, which are the hallmark of the disease.

Acute severe colitis can result in a fulminant colitis or toxic megacolon, which is characterized by a thin-walled, dilated colon that can eventually become perforated.

Pseudopolyps form in 15% to 20% of chronic cases. Chronic and severe cases can exhibit areas of precancerous changes, such as carcinoma in situ or dysplasia.

Classification

General

Left-sided colitis: inflammation up to the splenic flexure.

Extensive colitis: inflammation beyond the splenic flexure.

These categories are useful when formulating treatment options and planning the timing of surveillance colonoscopy, which is used to detect and prevent colorectal carcinoma.[3]

Montreal classification[4]

The Montreal classification proposes the maximal extent of involvement as the critical parameter:

E1 (ulcerative proctitis): involvement limited to the rectum (proximal extent of inflammation is distal to the rectosigmoid junction)

E2 (left-sided UC, also called distal UC): involvement limited to a portion of the colorectum distal to the splenic flexure

E3 (extensive UC): involvement extends proximal to the splenic flexure.

A major drawback of the extent-based classification is the instability of disease extent over time. Progression and regression have been identified and accepted. Approximately one third of patients with E1 or E2 disease will experience proximal disease extension, predominantly in the first 10 years from diagnosis.[5] Disease extent may regress over time, with regression rates estimated from a crude rate of 1.6% to an actual rate of 71% after 10 years.[6]

In addition to extent of disease, UC is classified by severity:

S0: clinical remission (asymptomatic)

S1 (mild UC): passage of ≤4 stools per day (with or without blood), absence of any systemic illness, and normal levels of inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR])

S2 (moderate UC): passage of >4 stools per day but with minimal signs of systemic toxicity

S3 (severe UC): passage of ≥6 bloody stools daily, pulse rate of at least 90 bpm, temperature of at least 99.5°F (37.5°C), hemoglobin level of <10.5 g/100 mL, and ESR of at least 30 mm/hour.

Fulminant disease correlates with >10 bowel movements daily, continuous bleeding, toxicity, abdominal tenderness and distention, blood transfusion requirement, and colonic dilation (expansion).

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer