Approach

The following findings would raise the clinical suspicion of PBC:[14][15]

Abnormal liver biochemistry: the finding of abnormal liver enzymes, in particular elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) concentrations, in the context of normal or less significantly elevated transaminases in a patient with no other apparent liver etiologic process.

Clinical features typical of PBC: these include fatigue, xanthelasma formation around the eyes, dry eyes and dry mouth (sicca complex), abdominal discomfort, and itch in the absence of an obvious skin cause, in particular where the perception is of itch deep under the skin. Excoriations that occur as a consequence of scratching activity can lead to a false clinical suspicion of primary skin disease. All these clinical features can occur in the absence of any features that would make the clinician specifically concerned about the possibility of liver disease. The majority of patients presenting with early-stage symptomatic PBC will not be jaundiced. In the majority of people in whom the diagnosis of PBC is missed it is, in a large part, because the presence of liver disease in general has not been suspected.

Characteristic features of advanced liver disease: these may occur in a patient presenting with no other apparent etiology. The clinical features in this scenario would be typical of cirrhosis, including metabolic changes (weight loss, muscle mass loss, and skin thinning) and portal hypertensive features (splenomegaly, ascites, and variceal bleeding). Jaundice is almost always prominent in patients with histologically advanced PBC.

History

It is important to note that many patients do not exhibit any of the characteristic clinical features suggestive of either PBC specifically or liver disease in general.

On history, in addition to the supportive clinical features outlined above, patients with PBC will frequently describe a positive family history of either PBC itself or of other autoimmune disease.[23] There is an increased risk of PBC in the relatives of patients with PBC, with the risk being greatest in first-degree female relatives ages 45-60 years.[24] There may also be a personal history of associated autoimmune disease. The strongest specific associations are with Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma, and celiac disease, although thyroid disease in particular should be considered as an associated disease in patients, because of its contribution to fatigue.

Symptoms of autonomic dysfunction, such as postural dizziness and loss of concentration, are occasionally seen.

Physical exam

Physical exam of patients without cirrhosis is usually unremarkable. Xanthelasmata or hepatomegaly are occasionally present, although nonspecific for PBC.

Patients with advanced cirrhotic disease will have the generic features of cirrhosis on physical exam.

Investigation

The diagnosis of PBC is based on three factors:[14][15]

The presence of cholestatic liver biochemistry with prominent elevation of ALP and/or GGT. Patients with early-stage disease will typically not be jaundiced, although in the late stages of disease bilirubin concentrations can be substantially elevated.

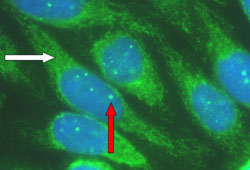

Autoantibody profile compatible with PBC: antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) or PBC-characteristic antinuclear antibody (ANA), such as anti-sp100 and anti-gp210.[16][25][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic autoantibody patterns in primary biliary cholangitis. White arrow: antimitochondrial staining; red arrow: multiple nuclear dot ANA stainingFrom the collection of DEJ Jones; used with permission. [Citation ends].

Autoantibody profile can be obtained with either immunofluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). AMA is present in 90% to 95% of diagnosed patients and is considered a hallmark of PBC.[14]

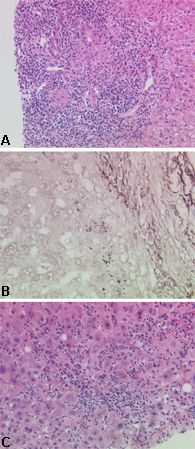

Autoantibody profile can be obtained with either immunofluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). AMA is present in 90% to 95% of diagnosed patients and is considered a hallmark of PBC.[14]Compatible or diagnostic liver histology on liver biopsy with, in particular, the presence of classic bile duct lesions accompanied by portal tract inflammation and granuloma formation. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic histologic appearances of primary biliary cholangitis: (a) early-stage disease; (b) advanced-stage disease; (c) disease with a significant inflammatory componentFrom the collection of Professor Alastair Burt, Newcastle University; used with permission. [Citation ends].

US and European clinical practice guidelines recommend that the diagnosis can be made when two of the three features are present.[14][15]

Biopsy is not usually necessary to confirm the diagnosis of PBC.[14][15] This is a reflection of the high value of serologic markers of the disease, the complications of biopsy, and the issues that can arise from sampling error in what is frequently a patchy disease.[26]

A test for fibrosis should be performed in all patients on diagnosis to stage the disease.

Imaging with abdominal ultrasound or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may be considered to rule out other causes of cholestasis and bile duct obstruction.

A subgroup of patients (<10% of the whole PBC population) have a more inflammatory process, interpreted by some in the field as a variant of PBC and by others as an overlap with autoimmune hepatitis.[14][15]

The presence of this inflammatory variant is confirmed by liver biopsy. The identification of this important subgroup of patients is one of the remaining indications for liver biopsy in PBC. Suspicion of this variant and indication for the need to perform a biopsy in this context is based on the following factors:

Presence of disproportionate elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

Presence of an elevated serum IgG concentration (>2 g/dL)

Presence of rapidly worsening fatigue

Less frequently, presence of hepatitis-relevant serologic markers, diffuse pattern ANA, or smooth muscle antibody, the absence of which does not preclude the possibility of the presence of an overlap process potentially responsive to immunomodulatory therapy.

Elevated polyclonal serum IgM concentrations are also seen in patients with PBC and, although not part of the classic diagnostic criteria, can be useful in cases where doubt has arisen.[27] The clinical significance of AMA- or PBC-specific ANA in the context of normal liver biochemistry is unclear. No treatment is warranted in this group, unless a significant degree of fibrosis is present, but observation for the future development of PBC is appropriate.

Assessment of severity and prognosis

Assessment of severity and prognosis can be difficult in practice, particularly in patients with early-stage disease. Blood-based or imaging-based noninvasive tests are preferred for assessing fibrosis; liver biopsy is no longer indicated for this purpose, unless in specific situations (e.g., absence of PBC-specific antibodies, suspicion of coexistence of autoimmune hepatitis or metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis [previously known as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] or other comorbidities), or when there is inadequate response to ursodiol therapy in order to characterize histologic lesions that underlie the resistance to treatment.[15] Moreover, the course of the disease may be progressive, despite treatment, thus noninvasive assessment of fibrosis is crucial at diagnosis and follow-up of these patients.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) suggests a combination of imaging-based and blood-based techniques to detect significant fibrosis and advanced fibrosis, particularly in those undergoing initial fibrosis staging.[28] Imaging-based tests may be preferentially incorporated into the initial fibrosis staging process owing to their higher accuracy over blood-based techniques and can help identify advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis in adults with chronic PBC.[28] Either transient elastography (TE) or magnetic resonance elastography is recommended by the AASLD to stage fibrosis in adults with chronic liver disease.[28] The AASLD advises against using imaging-based tests as a standalone test to assess regression or progression of liver fibrosis.[28]

Fibrosis stage is an independent predictor of outcome in PBC, even in patients with biochemical treatment response.[29] Liver stiffness measurement (LSM) by TE is the best surrogate marker for severe fibrosis.[30] Progression of liver stiffness is predictive of poor outcome.[14] European guidelines suggest repeating LSM every 2 years in patients with early-stage disease, and every year in patients with advanced stage disease.[30] Serum markers of fibrosis, including serum levels of hyaluronic acid, procollagen III aminoterminal propeptide, collagen IV, enhanced liver fibrosis test, and FibroTest®, are not recommended for fibrosis staging and should only be used where radiologic testing is unavailable. Similarly, noninvasive scores (e.g., APRI, FIB-4, AAR, red blood cell distribution width to platelet ratio, red blood cell distribution width to lymphocyte ratio, and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio) lack diagnostic accuracy and are not recommended.[30]

Patients with PBC treated with ursodiol demonstrate a different disease course depending on baseline (pre-treatment) features and biochemical response after 12 months of treatment. Risk stratification is required:[30]

At baseline - the distinction of early- from advanced-stage disease is based on LSM by TE, serum levels of bilirubin and albumin and, when available, histology.

On treatment - the evaluation of prognosis is based on the assessment of biochemical response to ursodiol after 12 months using qualitative criteria (e.g., Paris-I, Paris-II, Rotterdam, Toronto, Rochester, Ehime criteria), or recently proposed quantitative criteria (e.g., UK-PBC score and GLOBE score).[15][31][32] Multiple studies show a high risk of adverse events for patients with inadequate response to ursodiol one year after initiation; however, no single approach for classifying treatment response has been adopted uniformly.[27] Both the UK-PBC and GLOBE scores have been developed using data derived and validated from large cohorts, and have been shown to be superior to qualitative criteria, and to the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease and Child-Pugh scores.[15]

Individual concentration values for ALP and transaminases have no prognostic value. In population terms, the presence of PBC-specific ANA may be associated with a worse prognosis.[33][34] It is unclear, however, how the presence of such ANA should be interpreted in an individual patient and used to inform decisions regarding treatment.[35][36] Young age at diagnosis (<45 years) and male sex have also been associated with poor prognosis, as have the finding of interface hepatitis on histology and persistent elevation of serum aminotransferases.[27]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer