Approach

A diagnosis of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) (formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis) should be considered in all patients suspected of having a multisystem inflammatory disease on the basis of the signs and symptoms described below. Although careful history and physical exam are essential to establish disease extent, there is no single symptom or sign that is pathognomonic for the disease. Further evaluation of organ systems that are frequently affected by GPA in the absence of overt symptoms or signs is also required. At a minimum, this includes chest imaging, urinalysis, and urine microscopy.

Positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) testing can strongly support the diagnosis in patients with a moderate to high pretest probability of GPA. A positive ANCA test in the setting of the classic triad of typical otorhinolaryngeal, lung, and renal involvement is generally sufficient to make the diagnosis, even in the absence of histologic confirmation. However, a negative ANCA test does not exclude the diagnosis, and false positives may occur.

Demonstration of necrotizing vasculitis and granulomatous inflammation on tissue biopsy can confirm the diagnosis in the appropriate clinical setting. The differential diagnosis of GPA varies significantly with the pattern, extent, and severity of organ involvement.

Risk factors

GPA affects males and females equally. GPA is most commonly seen in white people, but may occur in any racial and ethnic group.[7][9][10] It is rare for there to be a family history of GPA specifically, but there may be a history of autoimmune disease.[14] Silica and other occupational exposures have been proposed as possible triggers for GPA, but this has not yet been proven.[16]

History

Because GPA is a multisystem disease, a thorough review of systems is required to assess the extent of organ involvement. More than 90% of patients present with signs and/or symptoms involving the upper or lower respiratory tract.[10] Symptoms that should be enquired about include:[1][2][3][21][22]

Upper respiratory tract manifestations:

Otorrhea

Pain/muffled sensation in ears

Deafness

Sinus pain

Nasal discharge

Nasal crusting

Epistaxis

Hoarseness

Oral and nasal ulcers.

Lower respiratory tract manifestations:

Shortness of breath

Cough

Hemoptysis

Chest pain.

Constitutional manifestations:

Fever

Night sweats

Malaise

Anorexia

Weight loss.

Neurologic manifestations:

Numbness/dysesthesias

Focal weakness

Headache.

Ocular manifestations:

Redness

Pain

Diplopia

Tearing

Visual blurring/loss.

Cutaneous manifestations:

Purpuric skin lesions

Nodular skin lesions

Hemorrhagic skin lesions

Ulcerative skin lesions.

Musculoskeletal manifestations:

Arthralgias

Myalgias

Joint swelling

Muscle weakness.

Less commonly, symptoms related to gastrointestinal (GI), endocrine, cardiac, breast, lower genitourinary (GU) tract, or other organ involvement may occur. The vast majority of patients will have involvement of at least two organ systems at the time of diagnosis. A history of leg pain and swelling should also be sought as there is a high incidence of signs or symptoms of venous thromboembolism in patients with GPA, particularly in association with periods of active disease.[4][5] Therefore, pulmonary embolus is an important differential diagnosis for patients with suspected GPA and respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath and hemoptysis.

Patients with subglottic disease usually give a history of hoarseness, cough, and wheeze.

Physical exam

Because of the multisystem nature of GPA, a thorough physical exam is required to assess the extent of organ involvement. Physical findings that should be sought include:[1][2][3][21][22]

Upper respiratory manifestations:

Mucosal bleeding

Inflammation

Ulceration

Crusting

Septal perforation on anterior rhinoscopy

Saddle nose deformity

Sinus tenderness

Aural drainage

Tympanic perforation.

Lower respiratory tract manifestations:

Dyspnea

Focal dullness to percussion

Crackles

Rhonchi

Focal reduction of air entry on auscultation.

Constitutional features:

Fever

Evidence of weight loss.

Neurologic manifestations:

Findings consistent with mononeuritis multiplex (i.e., preservation of reflexes and sensorimotor function generally, except in the regions served by the specific nerves affected)

Peripheral sensorimotor neuropathy or cranial neuropathy

Less commonly, focal central nervous system deficits (e.g., hemiparesis).

Ocular manifestations:

Scleritis

Proptosis due to retro-orbital granulomatous masses

Reduced visual acuity

Extra-ocular muscle weakness

Retinal exudates/hemorrhage.

Cutaneous manifestations:

Palpable purpura

Nodules

Hemorrhagic and ulcerative skin lesions.

Musculoskeletal features:

Joint tenderness or swelling

Muscle weakness

Signs of venous thrombosis (limb swelling/tenderness/erythema).

Less commonly, physical signs consistent with GI, endocrine, cardiac, breast, lower GU tract, or other organ involvement may be present.

Patients with subglottic stenosis may have stridor.[23] Laryngoscopy reveals a circumferential bank of red friable tissue narrowing the subglottis.[24]

GPA can also cause mass lesions/focal granulomas anywhere in the body; for example, involvement of the salivary glands, liver, and spleen have all been reported.[25][26][27] These lesions are frequently asymptomatic.

Laboratory testing

Urinalysis and microscopy:

This is performed in all patients with suspected GPA.[22] It is the earliest indicator of renal involvement, detectable prior to elevated serum creatinine. Typical findings include hematuria, proteinuria, dysmorphic red blood cells and red blood cell casts.

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA):

Antigen-specific immunoassay for proteinase 3 (PR3)-ANCAs and myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCAs is the preferred first screening method for ANCA-associated vasculitides.[28] Patients with GPA are predominantly PR3-ANCA positive.[29]

If immunoassay results are negative or equivocal, and a strong suspicion of GPA persists, indirect immunofluorescence may be performed.[28] Immunofluorescence may reveal cANCA (cytoplasmic pattern), pANCA (perinuclear pattern), or an atypical staining pattern. A cytoplasmic staining pattern is typical for GPA.[21]

A positive ANCA in the setting of typical symptoms is generally sufficient to diagnose GPA, even in the absence of histologic confirmation. However, a positive ANCA may also be seen in other settings, such as other systemic inflammatory disorders, GI disorders (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune hepatitis), infections (e.g., infective endocarditis, mycobacterial, and parasitic infections), malignancy, and drug exposures (e.g., cocaine, propylthiouracil, minocycline). Therefore, these conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis and, in cases where doubt exists, histologic confirmation of the diagnosis should be sought.[28]

A negative ANCA test does not rule out GPA.[28] Between 9% and 16% of patients with GPA have a negative ANCA immunoassay.[30][31]

While ANCA testing is helpful in making the diagnosis of GPA, evidence does not support the use of ANCA for monitoring of disease activity.[32]

Complete blood count and differential:

Patients with GPA are frequently anemic.[22] This may be related to a number of factors, such as disease activity, renal insufficiency or pulmonary hemorrhage. Thrombocytopenia or leukopenia should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses, such as systemic lupus erythematosus or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, depending on the clinical presentation.

Serum creatinine:

This is normally elevated in patients with GPA, although a normal result does not rule out glomerulonephritis.[22] It should be borne in mind that serum creatinine may also be elevated, due to other factors such as intercurrent sepsis, effects of medications, or, rarely, due to obstructive uropathy cause by GPA. Serum creatinine may change rapidly in the acute phase of the disease, so frequent monitoring is advised.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein:

Typically elevated in patients with GPA, but this is a nonspecific finding.[22] The result may be normal, especially in less severe disease presentations. Serial ESR results can be helpful in monitoring response to treatment and course of disease, but should not be used as the sole basis for treatment decisions as it can be influenced by many other factors (e.g., anemia, renal failure, intercurrent infection, and malignancy).

Liver function tests:

Typically normal or near-normal; abnormalities suggest an alternative diagnosis such as cancer or infection. Serum albumin may be low due to proteinuria and/or inflammation.[22]

Serum calcium:

Typically normal or near-normal; abnormalities suggest an alternative diagnosis such as cancer or infection.[22]

Imaging studies

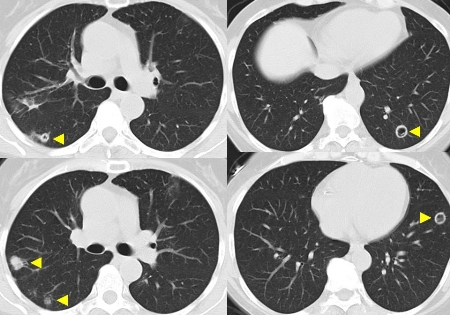

Chest imaging should be performed in all patients with suspected GPA, as lung involvement is asymptomatic in one third of patients.[22] Computed tomography (CT) of the chest is preferred to chest x-ray, due to its greater sensitivity.[33][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cavitary lung nodules in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis)From the collection of Dr Eamonn Molloy, used with permission [Citation ends].

If upper respiratory or otorhinolaryngeal manifestations are detected or suspected, then a CT of the sinuses is indicated. Mucosal thickening is frequently seen in GPA, but is nonspecific. Pansinusitis or a mucocele may also be seen. If disease has been chronic, bony reactive changes may be noted.[34] Perforation of a bony structure other than the lamina papyracea implies an alternative diagnosis such as infection or malignancy.

Biopsy

Biopsy may be indicated to support the diagnosis, depending on the presence of other clinical, laboratory, and imaging criteria.[21] Biopsies of the affected organs are recommended for patients with negative ANCA test results.[28] Typical pathological findings include granulomatous inflammation, necrosis, and vasculitis, with minimal or absent immune deposits on immunofluorescence and electron microscopy.

Yield from upper respiratory and transbronchial biopsies is low (<10%), so these should not be used to rule out the diagnosis. Open lung biopsy has a higher yield.

Renal biopsy lesions are indistinguishable from that of microscopic polyangiitis and renal-limited pauci-immune glomerulonephritis.

Skin biopsy shows leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Other tests

Depending on the exact nature of the presentation and the suspected organ involvement, a number of other tests may be relevant to diagnosis of GPA.

Pulmonary function testing:

An elevated diffusion capacity and/or an abnormal, box-like flow volume loop may indicate pulmonary hemorrhage and subglottic airway stenosis, respectively.

Bronchoscopy:

This can be helpful for detection of subclinical pulmonary hemorrhage, and airway stenoses. Microbiologic studies of bronchoalveolar lavage ± transbronchial biopsy specimens can be used to exclude infection, especially in patients treated with immunosuppressive agents. Transbronchial biopsies have a low yield (<10%) for the diagnosis of GPA, but may help identify competing diagnoses such as infection and malignancy.

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies:

These tests are only indicated in patients who display neurologic symptoms and signs. Findings that would support a diagnosis of GPA include peripheral sensorimotor polyneuropathy and mononeuritis multiplex.

Upper airway endoscopy:

In patients with upper respiratory tract manifestations, direct visualization of the upper airway can reveal features such as nasal crusting and inflammation, septal perforation, sinusitis, and subglottic stenosis. As well as its diagnostic role, this test also facilitates local management (e.g., dilatation and corticosteroid injection of subglottic stenosis) and allows for debridement of extensive nasal crusting and collection of specimens for microbiologic testing.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer