Approach

History

Dysuria

Timing: duration and onset of symptoms are important. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are commonly associated with a rapid onset of symptoms, while sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and urethritis are associated with a more gradual onset over days. Postcoital cystitis typically develops within a few days of intercourse. Vaginitis can have an insidious onset and can develop over weeks to months.

Location: external dysuria in women (i.e., urine irritating the inflamed genital organs) may suggest a gynecologic cause such as vaginitis, while in men it can suggest balanitis or balanoposthitis. Internal dysuria (i.e., pain felt in the urethra) in both sexes is most commonly caused by UTIs, cystitis, or urethritis. Pain at the onset of urination is often urethral in origin, while suprapubic pain often originates from the bladder.[31]

Severity.

Associated symptoms

Cloudy or malodorous urine often suggests an infectious cause.

Hematuria often indicates infection, but other important diagnoses such as malignancies, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), interstitial cystitis, trauma, and urolithiasis may also cause hematuria. History of hematuria should be considered a red flag so urologic malignancies are not missed.

Voiding symptoms such as a weak stream, hesitancy, intermittency, and dribbling are often caused by BPH or urethral stricture or stenosis. Occasionally, voiding symptoms may be due to decreased bladder contractility secondary to neurologic causes.

The presence of storage symptoms (i.e., frequency and urgency) in both sexes can be caused by urolithiasis, interstitial cystitis, infections, urethral hypersensitivity, detrusor overactivity, or malignancy.

Nocturia is the passage of urine more frequently at night and may occur in UTI or BPH.

Rectal or perineal pain and discomfort in men suggests prostatitis, although it is important to exclude other causes of rectal pain such as tumors or anal fissures.

Fever, rigors, myalgia, headache, nausea, and vomiting often suggest an infectious cause and, in particular, an upper UTI (e.g., pyelonephritis, especially if flank pain is present).

Sudden onset of colicky groin or flank pain may indicate urolithiasis.

Vaginal discharge may occur in vulvovaginitis and in STIs. The presence of vaginal discharge and a history of vaginal irritation both significantly decrease the likelihood of UTI when present.[32][33]

The presence of other systemic symptoms such as arthralgia and back pain, ocular symptoms (e.g., eye irritation), oral mucosal ulcerations, or gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea can point toward spondyloarthropathies such as reactive arthritis or Behçet syndrome.

Topical hygiene products, particularly in women, are associated with dysuria, especially cystitis. Scented soaps, vaginal sprays, vaginal douches, bubble baths, and sanitary products may cause symptoms, and their use should be ascertained in the history.[18][19][20]

Pneumaturia, incontinence, or passing debris in the urine suggests a urinary fistula.

Past medical history

A history of recurrent UTIs is associated with a higher risk of UTI in women.[34]

Identify patients with diabetes or who are immunocompromised. UTI and asymptomatic bacteriuria are common in patients with diabetes; infection may be more likely in patients with poorly controlled or advanced disease.[35][36] Pyelonephritis is more common in diabetes.[37][38][39]

History of inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, recurrent UTI, or pelvic radiation therapy may indicate a urinary fistula.

Past surgical history

A history of recent urinary instrumentation (e.g., cystoscopy, catheterization, surgery) should be noted.

Sexual history

A detailed sexual history in sexually active patients can often narrow the differential. Urethral discharge (thin and watery or thick and purulent) is most commonly associated with STIs.[40]

Use of spermicide and a diaphragm is associated with higher risk of UTI in women.[34]

Sexual abuse can lead to the development of dysuria.

Gynecologic history

Pregnancy should be excluded in women, as an untreated UTI is associated with premature labor and low-birthweight babies.[30]

Postcoital or intermenstrual bleeding may be present in urethritis or cervicitis. Associated dyspareunia is common in cervicitis and vaginitis. Cyclical premenstrual exacerbation of symptoms usually points to candidal or Trichomonas vaginitis.

Drug history

Drugs such as dopamine, cantharidin (used to treat warts and molluscum contagiosum), ticarcillin, penicillin-G, and cyclophosphamide, as well as illicit drugs such as ketamine, have been associated with dysuria.[17][21]

Social history

It is important to establish risk factors for urologic malignancies (e.g., smoking, exposure to chemicals, family history of malignancy).

A history of recent travel to endemic areas is important for the diagnosis of schistosomiasis.

Features such as fever, flank pain or tenderness, recent instrumentation, immunocompromise, recurrent episodes, and known urinary tract abnormalities should be considered red flags. Infective causes need to be identified and treated promptly. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Emphysematous cystitis: (A) horizontal CT slice showing increased emphysema, (B) coronal CT slice showing increased emphysema, (C) sagittal CT slice showing increased emphysemaMiddela S, Green E, Montague R. Emphysematous cystitis: radiological diagnosis of complicated urinary tract infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.05.2009.1832. Used with permission [Citation ends].

Physical examination

General examination

Review the patient's vital signs, with particular attention to excluding fever.

Assess the skin, mucosa, and joints, looking for evidence of spondyloarthropathies and autoimmune diseases (e.g., conjunctivitis, mucosal ulceration, crusting lesions on palms or soles and around nails, joint tenderness).

Abdominal examination

Palpate the abdomen, looking for signs of a distended bladder and suprapubic discomfort. However, only 15% to 20% of patients with cystitis and dysuria have suprapubic discomfort.[41] Suprapubic discomfort may also be present in urethritis, urethral hypersensitivity, urinary fistula, and ketamine bladder.

Flank percussion tenderness may indicate pyelonephritis.[39][42]

External genital examination

Examination of the fully retracted foreskin is mandatory in men; penile lesions or discharge may indicate an STI or malignancy.

Testicular exam: signs of erythema, swelling, or tenderness may indicate epididymitis or orchitis.

Digital rectal examination

A tender or boggy prostate on digital rectal exam may indicate prostatitis or prostatic abscess, while a smooth, benign enlargement may indicate BPH. A firm, nodular, or irregular prostate may indicate prostate cancer.

Prostatic massage may increase risk for bacteremia and should be avoided in suspected acute bacterial prostatitis.[12]

Pelvic examination

Pelvic examination should always be performed in persistent or recurrent infection.[43] It may be less essential when vaginal discharge and irritation are explicitly denied, and the rest of the history and examination point toward a different diagnosis.

Pelvic exam includes examination of the perineum, looking for signs of inflammation or lesions.

Examine the vagina and perineum in postmenopausal women for signs of atrophic vaginitis, which affects many postmenopausal women.[44][45] Atrophic areas of vaginal epithelium appear pale, smooth, and shiny. These areas can be friable and may develop patchy erythema and petechiae. Atrophic perineal skin has reduced turgor and elasticity.

Examination of the vaginal introitus can reveal evidence of uterine prolapse.

In patients where other urinary tract symptoms (such as urinary incontinence) are also present, or where prolapse or gynecologic malignancy is suspected, a speculum exam is essential. Speculum exam may reveal vaginal or cervical discharge.

Cervical motion tenderness during vaginal exam can indicate cervicitis or vulvovaginitis. Vaginal itching and a thick vaginal discharge can indicate vaginal candidiasis, but candidiasis may also present with an inflamed, red vagina with satellite vaginal pustules.

Grouped, painful vesicles and tender inguinal adenopathy suggest genital herpes.

Investigations

No single approach is uniformly accepted in the workup of dysuria, and tests should be directed by the most likely diagnosis. As for any diagnosis, an investigational hierarchy should be followed, starting with a simple urine dipstick test that can be performed in the clinic or office, followed by urinalysis and culture, or vaginal and urethral samples if appropriate. If further workup is required, radiologic and more invasive procedures, such as cystoscopy, may aid diagnosis.[46][47]

Initial evaluations

Urine dipstick: generally accepted as the first line of investigation. Leukocyte esterase has a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 98% for the detection of a UTI.[48] A positive nitrite test has a specificity of 90%, but a sensitivity as low as 30% for a UTI; sensitivity can be increased further with first-voided, morning urine samples (although not always possible in the clinical setting).[48][49] A combination of the nitrite and leukocyte esterase tests is recommended, which leads to a more accurate detection of a UTI (sensitivity of up to 88%).[48] In older adults (>65 years) and adults with indwelling urinary catheters, urine dipstick cannot be relied on to make a diagnosis of UTI; a full clinical assessment is required.[33][50]

Urine culture (clean-catch mid-stream urine [MSU]): in general, a finding of >10⁵ colony-forming units (CFU)/mL suggests a UTI.[51] However, lower counts of 10² to 10³ CFU/mL in symptomatic patients may be an early indication of a UTI.[52] A negative urine culture in a patient who was taking antibiotic therapy is unreliable. In women with contaminated specimens, a catheterized urine specimen may be obtained. In cases of suspected sexual abuse, cultures should be performed by a suitably qualified clinician, as they are 100% specific for infection and may be required in the judicial process.

Urine microscopy: hematuria in the absence of infection can be attributed to malignancy, urolithiasis, urethral trauma, or glomerular abnormalities. A finding of persistent microscopic hematuria (defined as >3 red blood cells per high-power field [HPF]) should prompt further evaluation with cystoscopy and upper tract studies.[53] Urine cytology may be useful for patients with persistent microscopic hematuria and irritative voiding symptoms or other risk factors for carcinoma in situ.[53] In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that people ages 60 and over who have unexplained nonvisible hematuria and dysuria are referred using a suspected cancer pathway referral for bladder cancer (for a diagnosis or ruling out of cancer within 28 days of the referral).[54] The presence of white blood cells in the absence of infection is nonspecific and may occur with STIs, vulvovaginitis, prostatitis, tuberculosis, or malignancy.

Urethral, vaginal, or cervical culture or nucleic acid amplification test: performed to identify STIs such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, mycoplasma genitalium, or herpes simplex infections. Serology for syphilis is required in all patients with a suspected STI, and human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) serology is required in high-risk groups.

Vaginal pH: useful in vaginitis. Normal vaginal pH is 3.5 to 4.5.[55] Vaginal pH is usually elevated in bacterial infections (including trichomoniasis) or atrophic vaginitis. Candidal infections are usually associated with normal pH. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy, vaginal pH, and yeast culture should be considered in women with chronic or recurrent dysuria of unknown etiology.

Pregnancy test: should be considered in women of childbearing age. An untreated UTI can lead to premature labor and low-birthweight babies. A positive pregnancy test will also guide antibiotic selection and preclude workup with ionizing radiation.

Imaging and pathologic tests

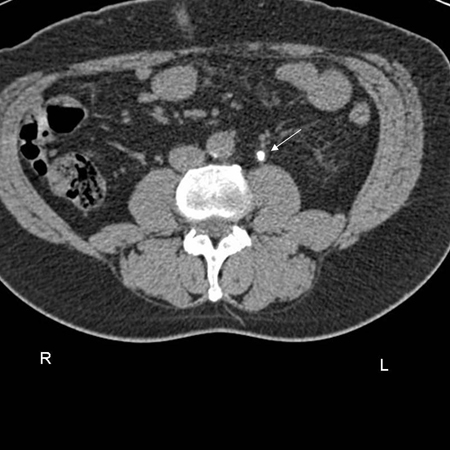

Ultrasound, intravenous urography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging: rarely required in most cases of dysuria, but they are essential in the diagnosis of urologic abnormalities such as urolithiasis, malignancy, cysts, vesicoureteral reflux, and bladder diverticulum.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing left ureteric calculiFrom the personal collection of Dr Kasra Saeb-Parsy [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing left renal stone (white arrow) with perinephric stranding around the left kidney (blue chevrons) and pyelonephritisFrom the personal collection of Dr Kasra Saeb-Parsy [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing left renal stone (white arrow) with perinephric stranding around the left kidney (blue chevrons) and pyelonephritisFrom the personal collection of Dr Kasra Saeb-Parsy [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder blocking the right ureteric orificeFrom the personal collection of Dr Kasra Saeb-Parsy [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder blocking the right ureteric orificeFrom the personal collection of Dr Kasra Saeb-Parsy [Citation ends]. Flow rate and postvoid residual, or urodynamic, studies are useful in the investigation of voiding or storage lower urinary tract symptoms.

Flow rate and postvoid residual, or urodynamic, studies are useful in the investigation of voiding or storage lower urinary tract symptoms.Prostatic ultrasound: used to evaluate the size of the prostate gland and to evaluate for prostatic abscess, and can be combined with biopsy to help diagnose prostate cancer.

Cystoscopy: to evaluate the anatomy of the lower urinary tract, evaluate for foreign bodies and tumors, and aid in the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis or urinary fistulae. Cystoscopy and urinary cytology should always be performed in the setting of persistent dysuria or storage urinary symptoms in the absence of UTI.

Biopsy of penile lesions: required for a diagnosis of penile cancer.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer