Approach

Many episodes of PID go unrecognized.[1] Although some cases are asymptomatic, others are not diagnosed because the patient or healthcare provider fails to recognize the implications of mild or nonspecific symptoms or signs (e.g., abnormal bleeding, dyspareunia, and vaginal discharge). Because of the difficulty of diagnosis and the potential for damage to the reproductive health of women, even by apparently mild or subclinical PID, healthcare providers should maintain a low threshold for the diagnosis of PID, particularly among the at-risk population for PID (e.g., sexually active women between the ages of 15 and 24, patients attending STI clinics, and those who live in other settings where the rates of gonorrhea or chlamydia are high).[1][21]

History

The history should focus on identifying risk factors for PID. A history of prior infection with chlamydia or gonorrhea is the most significant risk factor for PID.[10] Other key risk factors to elicit from the history include young age at onset of sexual activity, unprotected sexual intercourse with multiple partners, prior history of PID, and use of IUD.[10][12][13][14] A history of smoking, low socioeconomic status, current vaginal douching, and intercourse during menstruation should also be elicited. PID can cause a wide variety of nonspecific symptoms; nevertheless, the presence of these symptoms is highly suggestive and should be elicited:[22]

Lower abdominal pain, which is typically bilateral

Deep dyspareunia

Abnormal vaginal bleeding, including postcoital, inter-menstrual, and heavy menstrual bleeding

Abnormal vaginal or cervical discharge, which is often purulent

Secondary dysmenorrhea.

Physical examination

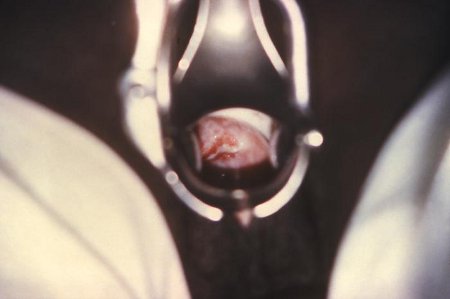

A systematic clinical examination, beginning with a general examination, is recommended. The general examination should include identifying a temperature (>101°F [>38.3°C]). Light and deep palpation of the abdomen would elicit any lower abdominal tenderness, which is usually bilateral. A pelvic examination should be performed, beginning with an inspection of the external genitalia looking for any obvious vaginal discharge. This is then followed by a speculum examination to expose the vagina and cervix and look for any mucopurulent or purulent exudate at the endocervix.[23] A bimanual examination is then performed to elicit one or more of the following minimum criteria:[1][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Signs of a cervical erosion and erythema due to chlamydial infectionCDC image library/Dr Lourdes Fraw, Jim Pledger; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gonococcal cervicitisCDC image library; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gonococcal cervicitisCDC image library; used with permission [Citation ends].

Cervical motion tenderness

Uterine tenderness

Adnexal tenderness.

Initial evaluation

One or more of the following additional criteria can be used to enhance the specificity of the minimum criteria and support a diagnosis of PID:[1]

Oral temperature >101°F (>38.3°C)

Abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability

Presence of abundant numbers of white blood cells on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid

Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Elevated C-reactive protein

Laboratory documentation (a vaginal swab is the specimen of choice) of cervical infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Additional laboratory tests

More elaborate diagnostic evaluation is frequently needed because incorrect diagnosis and management might cause unnecessary morbidity. When the diagnosis is questionable or the patient is not responding to therapy, further investigation is warranted. Several tests and procedures exist with varying costs and availability but no single laboratory test is diagnostic. However, in this context, normal results on serum white blood cell count and wet mount polymorphonuclear leukocytes effectively exclude upper genital tract infection.[3][24] These tests should be considered at initial consultation. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate can be considered but is usually only elevated in moderate or severe PID. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved a nucleic acid amplification for testing for Mycoplasma genitalium. Although the availability of M genitalium testing varies, UK guidelines strongly recommend testing to guide the choice of appropriate therapy.[22][25] European guidelines recommend that all M genitalium-positive nucleic acid amplification tests should be followed up with an assay capable of detecting macrolide resistance mutations. Sensitivity of macrolide resistance assays varies significantly.[26]

Imaging and invasive tests

Imaging is reserved for patients with uncertain clinical diagnosis, and for those who are severely ill or unresponsive to initial therapy. Imaging studies include transvaginal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Each study demonstrates findings characteristic of PID.

Transvaginal ultrasound is the primary imaging modality and may be normal in early stages or uncomplicated cases. Use of color or power Doppler can improve detection of subtle abnormalities of endometritis, salpingitis, and oophoritis.[27]

Pelvic CT is indicated in patients with diffuse pelvic pain, peritonitis, or difficult or equivocal ultrasound. It should be performed with both oral and intravenous contrast, as unopacified bowel may be mistaken for an abscess.[28]

Pelvic MRI is considered superior to ultrasound at diagnosing PID when there is a tubo-ovarian abscess, pyosalpinx, fluid-filled tube, and/or enlarged polycystic ovaries with free intrapelvic fluid. However, both ultrasound and CT are more cost effective than MRI. Therefore, MRI is rarely used and plays only a complementary problem-solving role.[28]

Laparoscopy enables specimens to be taken from the fallopian tubes and pouch of Douglas, and is particularly useful in obtaining a more accurate diagnosis of salpingitis and a more complete bacteriologic diagnosis. Laparoscopy will not detect endometritis or subtle inflammation of the fallopian tubes. It should not be used as a routine diagnostic tool, especially when symptoms are mild or vague.[1]

Endometrial biopsy should not be used as a routine diagnostic test. It is indicated in women undergoing laparoscopy who do not have visual evidence of salpingitis.[1]

Presumptive treatment

Empiric treatment of PID should be initiated in sexually active young women and other women at risk of PID (e.g., women ages between 15 and 24 years; women from a high-morbidity community [as defined by an increased prevalence]; those with individual risk factors [such as multiple recent sex partners, history of an STI, a partner with an STI]; and those connected to networks with incarcerated people, to the commercial sex trade, or to drug use) if no other cause of illness can be identified.[1] Due to serious health implications of untreated PID and lack of clear delineation of timing for invasive tests, physicians are advised to start treatment in patients at risk who have pelvic or lower abdominal pain, cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal tenderness.[1] These physical findings are noted in over 90% of women with laparoscopically documented disease.[14]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer