The goal of treatment is to eliminate the dangerous effects of excessive catecholamine production by the tumor. Surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment.

Hypertensive crisis

A hypertensive crisis (systolic BP >250 mmHg) may occur on presentation of a pheochromocytoma or during surgical resection of the tumor if the patient has not received adequate preoperative medical therapy.

Treatment includes immediate alpha blockade with an alpha-1 blocker (e.g., terazosin, doxazosin, or prazosin) or with the nonselective alpha-blocker, phenoxybenzamine. Intravenous agents (nitroprusside, phentolamine, or nicardipine) are short-acting and titratable, and can be used first line.[64]Nazari MA, Hasan R, Haigney M, et al. Catecholamine-induced hypertensive crises: current insights and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023 Dec;11(12):942-54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37944546?tool=bestpractice.com

Nitroprusside, phentolamine, or nicardipine can be added, as required, to an oral alpha-1 blocker prescribed in the initial management of hypertensive crisis.[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Clinical presentation will inform prescribing decisions. Consult a specialist when deciding on the most appropriate regimen.

Pretreatment alpha blockade

The first step in medical management is to block the effects of catecholamine excess by controlling hypertension and expanding intravascular volume.[1]Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 8;381(6):552-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31390501?tool=bestpractice.com

This is achieved by first establishing adequate alpha blockade.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Alpha-1 blockers (e.g., terazosin, doxazosin, or prazosin), or the nonselective alpha-blocker phenoxybenzamine, are recommended for initial pretreatment blockade.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

These drugs lower BP by decreasing peripheral vascular resistance.[65]Nicholson JP Jr, Vaughn ED Jr, Pickering TG, et al. Pheochromocytoma and prazosin. Ann Int Med. 1983 Oct;99(4):477-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6625381?tool=bestpractice.com

Alpha-1 blockers have a shorter duration of action than phenoxybenzamine, making them particularly useful in the perioperative period. The dose of alpha-1 blocker can be rapidly titrated, avoiding postoperative hypotension. These drugs do not enhance the release of norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and therefore do not cause a reflex tachycardia.

Hydration and a high-salt diet (>5 g/day) are given for 7-14 days (or until the patient is stable) to offset the effects of catecholamine-induced volume contraction associated with alpha blockade.[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Consider adding a calcium-channel blocker or metyrosine

Dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers can supplement alpha blockade if additional blood pressure control is required.[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Monotherapy with calcium-channel blockers is not recommended, but may be an option if the patient is unable to tolerate alpha blockade.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Nifedipine and amlodipine are the most commonly recommended dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers in the setting of perioperative pheochromocytoma BP control.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

Metyrosine can be used in conjunction with alpha blockade to stabilize blood pressure. Metyrosine, an inhibitor of tyrosine hydroxylase, inhibits catecholamine synthesis. In patients with pheochromocytomas, metyrosine can reduce the biosynthesis of catecholamines by 35% to 80%.[66]National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Database. Metyrosine. Nov 2019 [internet publication].

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Metyrosine

This is particularly useful in patients with very high circulating levels of catecholamines, which can be cytotoxic to myocardial cells.

Metyrosine also has a role in patients where tumor manipulation or destruction will be marked, such as patients with metastatic disease receiving chemotherapy.[67]Tada K, Okuda T, Yamashita K. Three cases of malignant pheochromocytoma treated with cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dacarbazine combination chemotherapty and alpha-methyl-p-tyrosine to control hypercatecholaminemia. Horm Res. 1998;49(6):295-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9623522?tool=bestpractice.com

It should be started 2 weeks prior to surgery. It can also be used when surgery is contraindicated.

Beta blockade after alpha blockade

Following adequate alpha blockade, which may take 3-4 days of therapy, beta blockade can be established to prevent and treat cardiac arrhythmia, as well as to manage hypertension.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

If beta blockade alone is used this can precipitate a hypertensive crisis due to unopposed alpha-adrenergic stimulation.[3]Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014 Jan-Feb;38(1):7-41.

https://www.cpcancer.com/article/S0147-0272(14)00002-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636754?tool=bestpractice.com

Combined alpha- and beta-adrenergic blockade is often used to control BP and prevent hypertensive crisis.

Benign pheochromocytoma

Surgical excision of the entire adrenal gland remains the mainstay of treatment for benign pheochromocytomas and is curative in more than 85% of cases.[68]Cryer PE. Diseases of the sympathochromaffin system. In: Felig P, Frohman LA, eds. Endocrinology and metabolism, 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:525-51.[69]Fung MM, Viveros OH, O'Connor DT. Diseases of the adrenal medulla. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2008 Feb;192(2):325-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18021328?tool=bestpractice.com

The treatment of choice for pheochromocytoma ≤6 cm is laparoscopic adrenalectomy.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

Bilateral disease can be successfully treated with adrenal-sparing surgery.[70]Petri BJ, van Eijck CH, de Herder WW, et al. Phaeochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas. Br J Surg. 2009 Dec;96(12):1381-92.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bjs.6821

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19918850?tool=bestpractice.com

Partial rather than total adrenalectomy should also be considered as first-line treatment for small adrenal tumors.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]Kaye DR, Storey BB, Pacak K, et al. Partial adrenalectomy: underused first line therapy for small adrenal tumors. J Urol. 2010 Jul;184(1):18-25.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20546805?tool=bestpractice.com

Removal is a high-risk surgical procedure requiring a skilled surgeon and anesthetic team. Complete excision is vital to prevent spread of the tumor and prevent other harmful effects of hypercatecholaminemia. Surgical complication rates are low; mortality rates of about 2% to 3% and morbidity rates of approximately 20% have been reported.[72]Kinney MA, Narr BJ, Warner MA. Perioperative management of pheochromocytoma. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002 Jun;16(3):359-69.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12073213?tool=bestpractice.com

Open adrenalectomy may be required to prevent rupture if the tumor is large (>6 cm), or to reduce local recurrence for invasive pheochromocytomas, or if malignancy is suspected.[2]Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/99/6/1915/2537399

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24893135?tool=bestpractice.com

[73]Plouin PF, Duclos JM, Soppelsa F, et al. Factors associated with perioperative morbidity and mortality in patients with pheochromocytoma: analysis of 165 operations at a single center. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Apr;86(4):1480-6.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/86/4/1480/2848250

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11297571?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Pacak KL, Eisenhofer G, Ahlman H, et al. Pheochromocytoma: recommendations for clinical practice from the First International Symposium. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Feb;3(2):92-102.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17237836?tool=bestpractice.com

Paragangliomas are extra-adrenal tumors. They require specialized surgical approaches depending on the various locations of origin.[70]Petri BJ, van Eijck CH, de Herder WW, et al. Phaeochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas. Br J Surg. 2009 Dec;96(12):1381-92.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bjs.6821

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19918850?tool=bestpractice.com

Surgical risk

The patients at highest risk for complications include those with severe preoperative hypertension or high catecholamine secreting tumors, and those undergoing repeat surgical interventions.[73]Plouin PF, Duclos JM, Soppelsa F, et al. Factors associated with perioperative morbidity and mortality in patients with pheochromocytoma: analysis of 165 operations at a single center. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Apr;86(4):1480-6.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/86/4/1480/2848250

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11297571?tool=bestpractice.com

Much of the risk associated with surgery is attributable to the risk of evoking a massive uncontrolled release of catecholamines due to manipulation of the tumor during resection. Complications are less likely with medical optimization and the current practice of strict perioperative BP control and plasma volume expansion.

Postoperatively, the sudden decrease in catecholamine levels can lead to hypotension and hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia may occur secondary to loss of the catecholamine-suppressed insulin secretion postoperatively. Treatment involves intravenous glucose replacement.[75]Akiba M, Kodama T, Ito Y, et al. Hypoglycemia induced by excessive rebound secretion of insulin after removal of pheochromocytoma. World J Surg. 1990 May-Jun;14(3):317-24.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2195784?tool=bestpractice.com

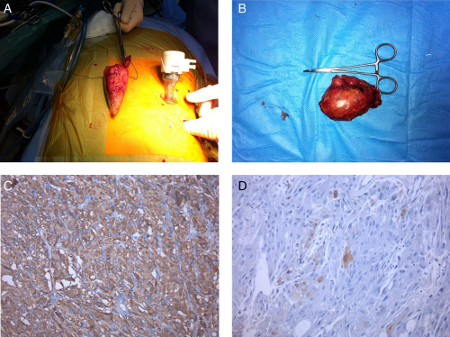

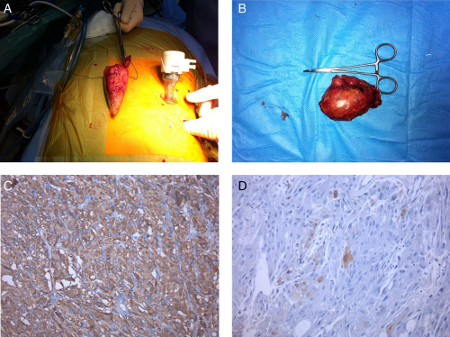

After the pheochromocytoma is removed, catecholamine secretion usually returns to normal within 1 week.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left laparoscopic adrenalectomy: (A) macroscopic examination, 6 cm tumor; (B) microscopic examination: neoplasm of the adrenal medulla with eosinophilic cytoplasm of large cells with positive fine granular chromogranin A; (C) round and oval nucleus and sustentacular cells S100+; (D) pheochromocytomaAlface MM et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Aug 4;2015:bcr2015211184; used with permission [Citation ends].

Metastatic pheochromocytoma

Malignant or metastatic pheochromocytomas represent 10% of all catecholamine-secreting tumors. The diagnosis is based on local invasion of surrounding tissues or distant metastases.

As in benign disease, surgical removal/debulking to improve symptoms is the primary therapy; however, this may not be possible if the tumor has extensive local or metastatic spread.[76]Adjallé R, Plouin PF, Pacak K, et al. Treatment of malignant pheochromocytoma. Horm Metab Res. 2009 Sep;41(9):687-96.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19672813?tool=bestpractice.com

Hypertension can be controlled with a combination of alpha- and beta-adrenergic blockade as well as calcium-channel blockers if needed.

Chemotherapy is given to all patients with metastatic disease after surgery.[61]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

Nonsurgical candidates with metastatic pheochromocytoma may also receive chemotherapy. Chemotherapy regimens usually consist of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine.[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[61]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

[77]Niemeijer ND, Alblas G, van Hulsteijn LT, et al. Chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dacarbazine for malignant paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014 Nov;81(5):642-51.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/cen.12542

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25041164?tool=bestpractice.com

Temozolomide, an alkylating drug and an alternative to dacarbazine, can be used as monotherapy or in combination with other antineoplastic drugs in patients with malignant pheochromocytomas and SDHB mutations.[78]Tena I, Gupta G, Tajahuerce M, et al. Successful second-line metronomic temozolomide in metastatic paraganglioma: case reports and review of the literature. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2018;12:1179554918763367.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5922490

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29720885?tool=bestpractice.com

[79]Tong A, Li M, Cui Y, et al. Temozolomide is a potential therapeutic tool for patients with metastatic pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma-case report and review of the literature. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7040234

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32132978?tool=bestpractice.com

The radiopharmaceutical, iobenguane I-131 (also known as I-131 metaiodobenzylguanidine [MIBG]), may be considered if I-123 MIBG scintigraphy was positive.

Painful skeletal metastases can be treated with external beam radiation therapy.[80]Breen W, Bancos I, Young WF Jr, et al. External beam radiation therapy for advanced/unresectable malignant paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2017 Nov 22;3(1):25-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.adro.2017.11.002

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29556576?tool=bestpractice.com

Radiofrequency ablation of hepatic and bone metastases may also be effective.[61]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

[81]Pacak K, Fojo T, Goldstein DS, et al. Radiofrequency ablation: a novel approach for treatment of metastatic pheochromocytoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001 Apr 18;93(8):648-9.

https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/93/8/648/2906558

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11309443?tool=bestpractice.com

Unresectable tumor

Patients with unresectable tumors have a:

malignant tumor with extensive local or metastatic spread that could not be removed by surgery, or

benign tumor and who is not a surgical candidate for other medical reasons (i.e., a patient who is a high surgical risk because of heart failure).

Long-term BP control in patients with unresectable tumors can be achieved with alpha and beta blockade, as well as calcium-channel blockers if needed.

Symptomatic patients with unresectable tumors have been treated with chemotherapy regimens (usually consisting of CVD) and/or iobenguane I-131 (also known as I-131 MIBG).[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[82]Pang Y, Liu Y, Pacak K, et al. Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas: from genetic diversity to targeted therapies. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Mar 28;11(4).

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30925729?tool=bestpractice.com

However, iobenguane I-131 based treatment is less likely to achieve complete response.[83]van Hulsteijn LT, Niemeijer ND, Dekkers OM, et al. (131)I-MIBG therapy for malignant paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014 Apr;80(4):487-501.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/cen.12341

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24118038?tool=bestpractice.com

In cases of malignant pheochromocytomas refractory to both radiation therapy and chemotherapy, enrollment in a clinical trial is suggested and other treatment options, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., sunitinib), peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (lutetium Lu 177 dotatate also known as 177Lu-DOTATATE), immunotherapy (e.g., pembrolizumab), and hypoxia-inducible factor 2 alpha inhibitors (e.g., belzutifan), considered on a case-by-case basis.[27]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[49]Nölting S, Bechmann N, Taieb D, et al. Personalized management of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Rev. 2022 Mar 9;43(2):199-239.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8905338

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34147030?tool=bestpractice.com

[84]Jimenez C, Xu G, Varghese J, et al. New directions in treatment of metastatic or advanced pheochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas: an American, contemporary, pragmatic approach. Curr Oncol Rep. 2022 Jan;24(1):89-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35061191?tool=bestpractice.com

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) at doses greater than 40 Gy has been shown to provide local tumor control and relief of symptoms at both soft tissue sites of metastases and painful bone metastases.[80]Breen W, Bancos I, Young WF Jr, et al. External beam radiation therapy for advanced/unresectable malignant paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2017 Nov 22;3(1):25-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.adro.2017.11.002

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29556576?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Fishbein L, Bonner L, Torigian DA, et al. External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) for patients with malignant pheochromocytoma and non-head and -neck paraganglioma: combination with 131I-MIBG. Horm Metab Res. 2012 May;44(5):405-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22566196?tool=bestpractice.com

Patient with hereditary pheochromocytoma

There is evidence in favor of cortical-sparing adrenalectomy in patients with hereditary pheochromocytomas.[70]Petri BJ, van Eijck CH, de Herder WW, et al. Phaeochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas. Br J Surg. 2009 Dec;96(12):1381-92.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bjs.6821

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19918850?tool=bestpractice.com

This method can avoid the need for lifelong corticosteroid therapy. However, patients need to be monitored postoperatively for local recurrence.[86]Yip L, Lee JE, Shapiro SE. Surgical management of hereditary pheochromocytoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2004 Apr;198(4):525-34.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15051000?tool=bestpractice.com