Approach

Diagnosis is based on the history, including childbirth and any trauma or fall onto the buttocks. Physical exam includes palpation of the sacrum and coccyx, and rectal exam. Additional workup includes imaging studies, including dynamic sacrococcygeal lateral x-rays, and MRI of the sacrum and coccyx.

History

May be post-traumatic, nontraumatic, or idiopathic in origin.[5][7][8] Often there is a history of antecedent trauma or childbirth, possibly with a latent period between the incident and the development of symptoms. There is a 5:1 incidence in females versus males, and obesity is considered a strong risk factor for the development of coccygodynia.[5]

Patients usually complain of lancinating (i.e., stabbing or piercing), aching, or boring pain in the coccyx, which significantly impacts on normal activities. It may be worse with sitting, transitioning between standing and sitting, and occasionally with defecation and sexual intercourse. Pain may radiate to the sacrum and lumbar spine, and occasionally down the back of the thigh.

Acute coccygodynia is classified as symptoms present for <2 months, whereas chronic coccygodynia is classified as symptoms present for ≥2 months.

Physical exam

On observation, patients with coccygodynia may sit on their hands or elevate one buttock to avoid pressure on the sacrum (known as "guarding").

Exam reveals tenderness on external or transrectal palpation and movement of the coccyx. Rectal exam typically reveals tenderness on palpation of the coccygeal tip, or hypermobility of the coccyx, or both. Spasm or tenderness of the pelvic floor musculature may also be present.

A therapeutic trial with a corticosteroid (e.g., dexamethasone, methylprednisolone) and a local anesthetic (e.g., lidocaine, bupivacaine) injected around the dorsal surface of the coccyx can help distinguish true coccygodynia from referred pain (pseudococcygodynia) and often results in rapid relief of symptoms.

Laboratory investigations

Laboratory studies are usually not indicated; however, white blood cell count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be elevated in pelvic infections or inflammatory conditions, and should be ordered if suspected, as evidenced by redness and swelling in the perineal area.

Imaging

All patients should receive a lateral sacrococcygeal x-ray in both the standing and sitting positions. This reveals the patient's coccygeal configuration. Different coccygeal configurations have been described:[4][19]

Type 1: normal, curved slightly forward, seen in 68% of the general population

Type 2: curved forward 90°

Type 3: sharply angulated at the first or second intercoccygeal joint

Type 4: anterior subluxation

Type 5: coccygeal retroversion with spicule

Type 6: scoliotic deformity.

Patients with coccygodynia are more likely to have type 3 and 4 configurations, and less likely to have type 1 configuration, than people without coccygodynia.[19][20] Patients with coccygodynia are more likely to have fusion of the sacrococcygeal joint (51% versus 37% in people without coccygodynia).[19][20]

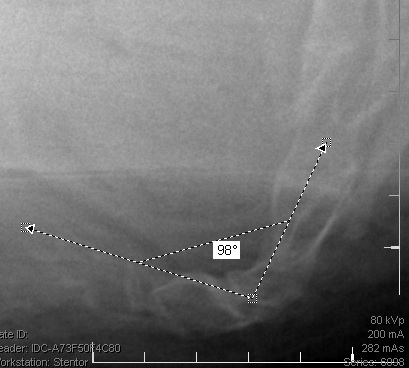

Dynamic lateral sacrococcygeal radiographs are used to compare changes between standing and painful sitting. Radiographic instability as evidenced by posterior subluxation and hypermobility (>20° of sacrococcygeal or intercoccygeal angulation) is seen in approximately 70% of patients with coccygodynia.[16][21] Radiographic instability is seen in 56% of cases of post-traumatic coccygodynia and 53% of idiopathic coccygodynia.[5] Other lesions include anterior subluxation and a bony spicule on the dorsal tip of the coccyx (seen in 5% and 14% of coccygodynia, respectively).[21]

Noncontrast MRI of the sacrum and coccyx is recommended in all patients to define normal and abnormal bony anatomy and to rule out less common causes of coccygodynia, such as abscess or tumors.[20] A contrast study may be done if clinically indicated.

CT may be superior to MRI in defining normal and abnormal bony anatomy. CT should be ordered in cases of acute pelvic trauma and as an adjunct to MRI in evaluating metastatic neoplastic disease.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lateral sacrococcygeal x-ray in a patient with post-traumatic chronic coccygodynia, showing sacrococcygeal synostosis (fusion, normal variant) and Co1-Co2 anterior subluxationFrom the personal collection of Dr R. Schrot [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Dynamic lateral sacrococcygeal x-ray in a patient with chronic idiopathic coccygodynia, showing 30° of anterior flexion while standingFrom the personal collection of Dr R. Schrot [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Dynamic lateral sacrococcygeal x-ray in a patient with chronic idiopathic coccygodynia, showing 30° of anterior flexion while standingFrom the personal collection of Dr R. Schrot [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Dynamic lateral sacrococcygeal x-ray in a patient with chronic idiopathic coccygodynia, showing 30° of anterior flexion while sittingFrom the personal collection of Dr R. Schrot [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Dynamic lateral sacrococcygeal x-ray in a patient with chronic idiopathic coccygodynia, showing 30° of anterior flexion while sittingFrom the personal collection of Dr R. Schrot [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer