History and exam

Key diagnostic factors

common

hearing loss

Commonly presents with a conductive hearing loss.[1] There may be a mixed conductive and sensorineural hearing loss in patients with cochlear damage or in those with a pre-existing hearing loss (e.g., congenital or presbycusis). Hearing may be normal in some patients.

ear discharge resistant to antibiotic therapy

Recurrent or chronic purulent aural discharge that may be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy is common in acquired cholesteatoma.

Discharge is malodorous and may be scant.

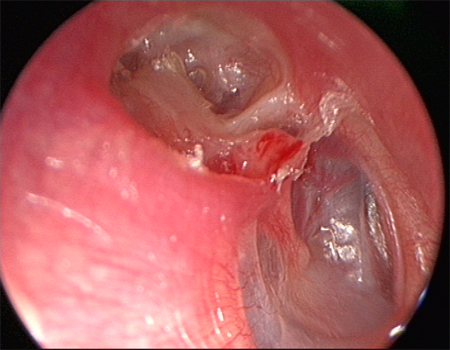

attic crust in retraction pocket

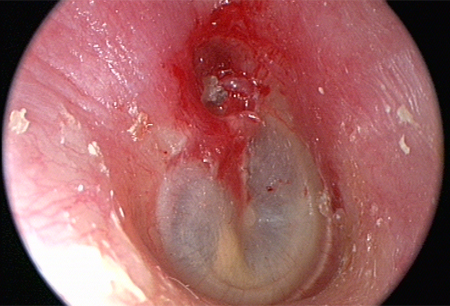

Otoscopy typically shows crust or keratin in the attic (upper part of the middle ear), the pars flaccida, or the pars tensa (usually posterior superior aspect), with or without a perforation of the tympanic membrane.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Retraction pocket in attic (upper part of the middle ear)From Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cholesteatoma in attic (upper part of the middle ear)From Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cholesteatoma in attic (upper part of the middle ear)From Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends].

uncommon

white mass behind intact tympanic membrane

Occurs in congenital cholesteatoma.

Other diagnostic factors

common

tinnitus

May be associated with hearing loss; occurs in the affected ear.

uncommon

otalgia

Uncommonly found. Pain may be a feature of advanced disease.

altered taste

Occurs due to involvement of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII).

dizziness

Occurs if there is erosion of the semicircular canal with the disease.

Risk factors

strong

middle ear disease

Acquired cholesteatoma is usually associated with eustachian tube dysfunction, often with a previous history of middle ear disease such as otitis media.[4]

eustachian tube dysfunction

Typically due to otitis media. Eustachian tube dysfunction promotes invagination of the tympanic membrane, which becomes pulled into the middle ear space because of the negative pressure (vacuum-like) effect.[16] This forms a retraction pocket.

These pockets are initially self-cleansing. However, the neck of the pocket then narrows and traps squamous cells, expands in size, and leads to cholesteatoma formation.[3]

otologic surgery

May lead to implantation of viable keratinocytes into the middle ear cleft, which can result in cholesteatoma formation.[4]

traumatic blast injury to ear

May lead to implantation of viable keratinocytes into the middle ear cleft, which can result in cholesteatoma formation.[4]

weak

family history

Children with a family history of middle ear disease and/or cholesteatoma have an increased risk of developing cholesteatoma.[16][21] One Swedish case-control study using nationwide register data found that the risk of cholesteatoma was strongly associated with a family history of the condition, suggesting a possible genetic predisposition; family history was nevertheless quite rare and could therefore only explain a limited number of all cases.[13]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer