Etiology

The term cholesteatoma was first used in a case report in 1838 to describe a ‘‘tumor” thought to be made of cholesterol and fat (chole - for cholesterol, steat - for fat, and oma - for tumor). This term remains in use despite the understanding that cholesteatoma is a progressively enlarging and destructive lesion composed of keratinizing squamous epithelium.[15]

Cholesteatoma may be considered acquired or congenital.

Acquired cholesteatoma occurs in several ways. In many cases, it is due to retraction of an area of the pars flaccida with or without associated atrophy of the pars tensa.[3] The epithelium becomes trapped and infected, and proliferates to form a cholesteatoma. Alternatively, squamous epithelium may migrate through a defect in the tympanic membrane, or the cholesteatoma may form due to implantation of viable keratinocytes into the middle ear cleft following otologic surgery or after a traumatic blast injury. Children with a cleft palate, craniofacial abnormality, or a chromosomal disorder (e.g., Turner or Down syndrome), have an increased risk of developing cholesteatoma.[4][8] This increased risk is secondary to poor eustachian tube function.

Congenital cholesteatoma is present if there is no history of previous ear surgery and no perforation or retraction of the tympanic membrane. It is believed to arise from developmental epidermoid rests present before birth that persist in the middle ear space.[4][16] Alternative theories include: invagination of squamous epithelium from the developing ear canal; seeding of the middle ear by squamous cells in the amniotic fluid; epithelial ingrowth from the surface of the tympanic membrane after infection; and microperforation.[4][16]

Pathophysiology

A retraction pocket is an area of invagination of the tympanic membrane that becomes pulled into the middle ear space because of the negative pressure (vacuum-like) effect of eustachian tube dysfunction.[16] These pockets are initially self-cleansing. They are graded or staged according to the degree of severity:[17]

Stage 1: retracted membrane

Stage 2: retraction onto the incus

Stage 3: middle ear atelectasis

Stage 4: adhesive otitis media

They are often found as the initial step in acquired cholesteatoma in adults or children; it is difficult to predict which pockets will develop into a cholesteatoma.[18] The neck of the pocket may narrow and trap squamous cells, with keratin accumulation and retention; these cells proliferate, leading to expansion and cholesteatoma formation.[3] This may occur as papillae migrating through a temporary defect in the pars flaccida, or around a pars tensa perforation (marginal perforation). Less commonly there is proliferation of the basal layers of keratinizing epithelium of the pars flaccida.[4] Bacterial infection and super-infection of the trapped debris form a biofilm and cause chronic infection and epithelial proliferation, leading to further lesion expansion and cholesteatoma formation.[3][19] There is often infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa species.[20]

Once formed, the cholesteatoma sac is associated with enzymatic bony destruction due to cytokine-induced inflammatory changes, with activation of osteoclasts and lysozymes.[1] Cholesteatoma is often associated with destruction of the ossicles causing a conductive hearing loss, and may be associated with destruction of the semicircular canals (with resulting vertigo), cochlea (with resulting sensorineural hearing loss), and facial canal (with resulting facial palsy).

Clinical and histologic evidence suggests that cholesteatoma in children tends to be more aggressive.[14]

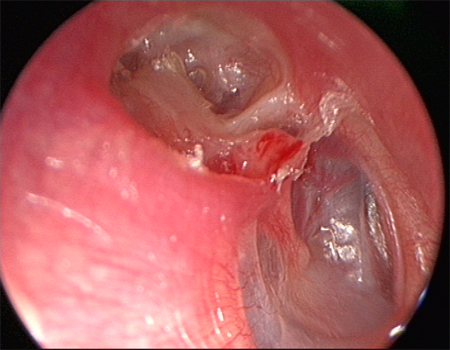

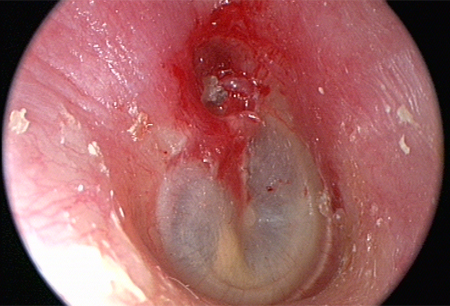

Congenital cholesteatoma may present as an epidermoid cyst behind an intact tympanic membrane. It is often found in the anterior superior aspect of the middle ear. This frequently arises above the eustachian tube orifice and obstructs it early in its course, leading to a middle ear effusion. As the lesion grows, it makes contact with the underside of the tympanic membrane and becomes more obvious. With time, it can replace the middle ear space and displace the tympanic membrane outward.[16][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Retraction pocket in attic (upper part of the middle ear)From Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cholesteatoma in attic (upper part of the middle ear)From Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cholesteatoma in attic (upper part of the middle ear)From Dr Susan Douglas' personal teaching collection [Citation ends].

Classification

Etiopathological classification[3]

Acquired cholesteatoma is usually associated with eustachian tube dysfunction, often with a previous history of middle ear disease. Acquired cholesteatoma affects both children and adults and can be subdivided into primary and secondary subtypes.[1]

Primary: occurs as a consequence of retraction pocket formation within the tympanic membrane subsequent to eustachian tube dysfunction, with invagination of squamous cells into the middle ear.

Secondary: occurs due to migration of squamous epithelium through an established tympanic membrane defect (marginal perforation), or due to implantation of viable keratinocytes into the middle ear cleft following otologic surgery or after a traumatic blast injury.

Congenital cholesteatoma is believed to arise from developmental epidermoid rests present before birth that persist in the middle ear space.[4]

European Academy of Otology and Neurotology/Japanese Otological Society Staging System[5]

The European Academy of Otology and Neurotology (EAONO) and Japanese Otological Society (JOS) working group developed a staging system that applies to four categories of middle ear cholesteatoma: pars flaccida cholesteatoma, pars tensa cholesteatoma, congenital cholesteatoma, and cholesteatoma secondary to a pars tensa perforation. This staging system does not apply to petrous bone cholesteatoma.

This system may be used for evaluating initial pathology in a standardized fashion. It may also be used to adjust for the severity of the condition during outcome evaluations, as well as providing information that is useful for counseling patients.

Stage 1: Localized cholesteatoma (described based on the primary site of origin)

The attic for pars flaccida cholesteatoma

The tympanic cavity for pars tensa cholesteatoma

Congenital cholesteatoma

Cholesteatoma secondary to a pars tensa perforation

Stage 2: Cholesteatoma involving two or more sites.

Stage 3: Cholesteatoma with extracranial complications or pathologic conditions. These include: facial palsy; labyrinthine fistula; labyrinthitis; postauricular abscess or fistula; zygomatic abscess; neck abscess; canal wall destruction more than half the length of the bony ear canal; destruction of the tegmen, with a defect that requires surgical repair; and adhesive otitis.

Stage 4: Cholesteatoma with intracranial complications. These include: purulent meningitis, epidural abscess, subdural abscess, brain abscess, sinus thrombosis, and brain herniation into the mastoid cavity.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer