Approach

Many mediastinal tumours are asymptomatic (incidental finding) or associated with only vague complaints. The likelihood of malignancy depends on mass location, patient age, and the presence of symptoms.[11][44][45]

Malignant masses are found in the prevascular (anterior), visceral (middle), and paravertebral (posterior) mediastinum in approximately 60%, 30%, and 15% of cases, respectively.[10] Symptoms are present in 80% to 90% of patients with malignant mediastinal tumours at presentation, compared with 46% of patients with benign masses.[10]

Approximately 25% of patients with thymoma have myasthenia gravis, and 15% of patients with myasthenia gravis have thymoma.[46] Neurogenic tumours are commonly observed in children. Acute lymphocytic leukaemia may occur in children (commonly <5 years) or adults. Lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, thymomas, and thyroid tumours tend to occur in adults.[47][48]

History

Although many mediastinal tumours may be asymptomatic, certain symptoms may raise concern for a mediastinal tumour and relate to its location. These include the following:

Airway compression: dyspnoea, stridor, haemoptysis, cough

Oesophageal compression: dysphagia, odynophagia, weight loss

Recurrent laryngeal nerve compression: hoarse voice

Superior vena cava obstruction: facial swelling, headache

Sympathetic ganglion involvement: Horner's syndrome, in which the patient may note pupillary constriction (miosis), drooping eyelids (ptosis), and absence of sweating (anhidrosis)

Chest wall invasion: myasthenic pain, palpable mass

Myasthenic symptoms: easy fatigability, drooping eyelid, double vision, dysarthria

Constitutional symptoms of malignancy: weight loss, night sweats, fever.

Physical examination

The mediastinum is inaccessible to direct physical examination except during surgery. Specific physical findings are related to compression or invasion of adjacent structures, or paraneoplastic syndromes:

Airway compression: stridor, prolonged inspiration/expiration, haemoptysis

Recurrent laryngeal nerve compression: hoarseness

Superior vena cava obstruction: facial swelling, collateral veins, plethora

Sympathetic ganglion involvement: Horner's syndrome, with miosis, ptosis, and anhidrosis

Myasthenic symptoms: ptosis, diplopia, dysarthria, proximal muscle weakness

Evidence of haematological malignancy: fever, pallor, petechiae, hepatosplenomegaly, abdominal mass.

Laboratory tests

Laboratory testing is indicated depending on the suspected aetiology:

Thymoma: FBC and acetylcholine receptor antibodies

Mediastinal goitre: thyroid function tests

Parathyroid adenoma: serum calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone

Germ cell tumour: alpha-fetoprotein, beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin

Phaeochromocytoma: plasma free metanephrines (also known as metadrenalines), or 24-hour urine fractionated metanephrines (also known as metadrenalines) and normetanephrines (also known as normetadrenalines)

Neurogenic tumour: 24-hour urinary homovanillic acid and vanillylmandelic acid

Haematological malignancy: lactate dehydrogenase, FBC and blood smear, flow cytometry, HIV serology, hepatitis B and C serology.

Imaging studies

Imaging to evaluate mediastinal mass typically employs a stepwise approach beginning with chest radiography.

Chest x-ray

Posteroanterior and lateral views are usually indicated.[49] Provides information on the size, anatomical location, density, and composition of the mass.

Computed tomography (CT)

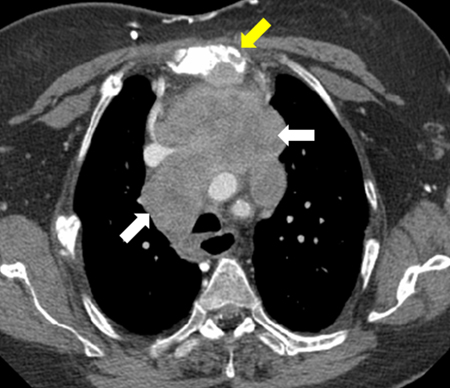

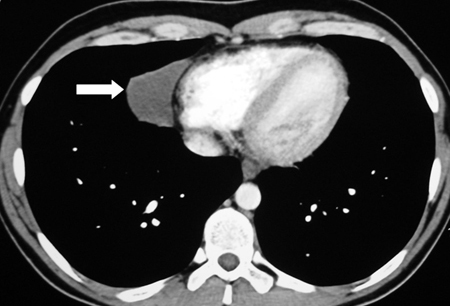

CT with intravenous contrast enhancement provides information concerning the vascularisation of the mass and its relationship to adjacent structures.[49] It can determine the content (calcium, fat, or necrotic tissue) and characteristics (cystic or solid) of the mass. CT scan is an essential test and is indicated in virtually all cases to evaluate a mediastinal mass.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT image of large thymic carcinoma (white arrow) with sternal invasion (yellow arrow)From the collections of Dr Mario Gasparri and Dr Nicholas Choong [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT image of pericardial cystFrom the collections of Dr Mario Gasparri and Dr Nicholas Choong [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT image of pericardial cystFrom the collections of Dr Mario Gasparri and Dr Nicholas Choong [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Necrotic mediastinal lymphadenopathyFrom the collections of Dr Mario Gasparri and Dr Nicholas Choong [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Necrotic mediastinal lymphadenopathyFrom the collections of Dr Mario Gasparri and Dr Nicholas Choong [Citation ends].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Provides useful information in evaluating spinal, vascular, or cardiac invasion.[49] MRI facilitates an assessment of the relationship of the mass to vascular structures, and provides the highest level of information regarding cystic versus solid components of thymic lesions (which can be important to differentiate thymomas from benign hyperplasia or thymic cysts).[50]

In the evaluation of the paravertebral (posterior) compartment of the mediastinum, MRI is more sensitive than CT for determining involvement of the neural foramen or spinal canal invasion. MRI is also useful for evaluating thyroid masses when iodinated contrast is contra-indicated.

Barium swallow

Assesses the relationship of an oesophageal cyst to the oesophagus proper, and determines whether there is a communication with the oesophageal lumen, which is the case in approximately 10% to 20% of patients.[51]

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)

May be used to differentiate between an intramural or extramural mass and delineate the relation of an oesophageal or bronchogenic cyst to surrounding structures.

Testicular ultrasound

Has a high sensitivity and is able to detect intratesticular lesions as small as 2 mm; indicated if germ cell tumour is suspected.

Radionuclide studies

Nuclear scans and biochemical studies are useful in diagnosing and evaluating the following conditions.

Suspected substernal thyroid

Radioactive iodine thyroid scan to define the nature and extent of thyroid gland; toxic multinodular goitre shows multiple hot and cold areas consistent with areas of autonomy and suppression; malignant thyroid nodules are generally cold.

Suspected catecholamine-secreting tumour

Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan to define the nature and extent of the tumour.

Malignancy

Fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET scan to define the extent and stage of a malignancy. 18F-FDG uptake occurs in most malignancies including lymphomas, metastatic carcinomas, and lung cancers.

18F-FDG PET-CT is effective in detecting lymph node metastases and extrathoracic metastases in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). It confers significantly higher sensitivity and specificity than contrast-enhanced CT and higher sensitivity than 18F-FDG PET in staging NSCLC.[52][53]

Neuroendocrine tumour

Gallium 68 or GaTate PET-CT scans are especially suited for diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumours, such as thymic carcinoid. They increase the sensitivity with which metastatic disease can be identified.[54]

Biopsy techniques

While clinical assessment in combination with radiographic imaging can often narrow the diagnostic possibilities, definitive pathological diagnosis is often required prior to initiating therapy. There are many modalities to obtain a pathological diagnosis, and each modality has its advantages and limitations.

Image-guided percutaneous needle biopsy

Performed with either CT or ultrasound, using local anaesthesia and light sedation. Samples are taken using either a fine needle or a core needle. It is mainly indicated for prevascular (anterior) mediastinal masses.

Image-guided percutaneous needle biopsy is minimally invasive, associated with low risk, and can be done as an outpatient procedure.[55] Tissue may, however, be insufficient to render a definitive diagnosis, especially with lymphoma and thymoma.

Endoscopic biopsy with or without ultrasonography

Can be performed bronchoscopically (combined endobronchial ultrasound, EBUS) or through the oesophagus (EUS) using a fine needle.[56] The accessible areas are those immediately adjacent to the tracheobronchial tree and oesophagus, which limits what can be biopsied. The American Thoracic Society has standardised the nomenclature of lymph nodes in the chest. There are 14 numbered nodal stations; lymph nodes considered to be in the mediastinum are stations 1 to 9. EBUS can access mediastinal nodal stations 2, 4, and 7, while EUS can access nodal stations 5, 7, 8, and 9.

EBUS is minimally invasive, associated with low risk, and can be done as an outpatient procedure.[57] Use of EBUS may reduce the need for surgical staging via mediastinoscopy.[58] However, only limited areas are amenable to biopsy with EBUS.

Mediastinoscopy

A surgical procedure requiring general anaesthesia. Incision is made just above the manubrium, and a mediastinoscope is passed along the pretracheal plane into the mediastinum. The high (station 2) and low (station 4) paratracheal lymph nodes, as well as the subcarinal lymph nodes (station 7) can be sampled. It is generally used for diagnosis and staging of lung cancer or lymphoma. Mediastinoscopy has the same accuracy as combined EBUS and EUS, with greater accuracy when all tests are taken together.[58] However, mediastinoscopy is an invasive procedure, and endobronchial ultrasound is increasingly used instead. The risk of major complications, such as great vessel injury, is low.

Mediastinotomy/Chamberlain procedure

Typically used for masses of the anterior mediastinum or within the aortopulmonary window. A small transverse parasternal incision allows excellent exposure and has a high diagnostic yield. It is an invasive procedure requiring general anaesthesia and may require tube thoracostomy if the pleural space is violated.

Thoracoscopy

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), a minimally invasive surgical technique, is a valuable tool in the diagnosis and management of mediastinal masses. Almost all traditionally open procedures can be performed via VATS, including thymectomy, duplication cyst excision, pericardial cyst excision, and paravertebral (posterior) mediastinal mass resection. It allows excellent exposure of all compartments of the mediastinum for diagnostic biopsy or therapeutic excision. VATS also permits the accurate determination of local invasion or intrapleural metastatic spread. VATS typically requires general anaesthesia, but awake VATS has been reported and is used in some centres, particularly in Europe and Asia.[59] VATS procedures may be performed with robotic assistance, with excellent outcomes.[60]

Sternotomy or thoracotomy

Sternotomy gives excellent exposure to the prevascular (anterior) mediastinum, and thoracotomy gives excellent exposure to the visceral (middle) and paravertebral (posterior) mediastinum. Sternotomy or thoracotomy is useful when excision of large lesions (>5 to 7 cm) is required, or if there is invasion into adjacent structures requiring complex resection and reconstruction (such as the SVC, diaphragm, or pericardium).

Bone marrow biopsy

Indicated if clinical features are suggestive of an underlying haematological malignancy such as lymphoma or acute or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

Peripheral lymph node biopsy

Haematological and metastatic malignancies may have abnormal lymph nodes peripherally. Excision of a complete lymph node provides valuable information on the malignant cell type based on histological appearance or immunohistochemical staining. Architecture assessment through complete excisional lymph node biopsy is particularly important for diagnosis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer