Aetiology

The aetiology of a mediastinal mass can be suggested by its location within the mediastinum. A mass may extend beyond the boundaries of these radiographically-defined compartments as it grows or invades; however, in general, the differential of mediastinal masses can be narrowed by the location of its epicentre.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Aetiology of mediastinal mass limited by locationCreated by BMJ Evidence Centre [Citation ends].

Thyroid masses (goitre, neoplasm)

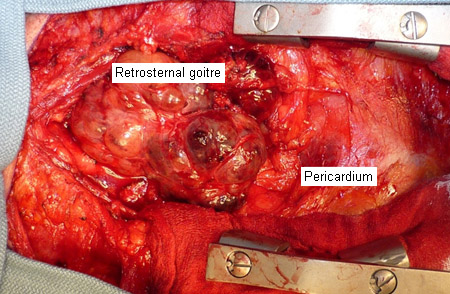

Substernal thyroid goitre most commonly represents direct extension of the thyroid gland into the prevascular (anterior) mediastinum. Goitres and ectopic thyroid tissue can also occur in the visceral (middle) mediastinum. Follicular adenoma is the most common benign neoplasm in substernal goitres.[3] Malignancy is present in 10% to 15% of substernal goitres.[4][5][6][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intra-operative view of retrosternal goitreFrom the collections of Dr Mario Gasparri and Dr Nicholas Choong [Citation ends].

Lymphadenopathy (metastatic, lymphoma)

Lymphadenopathy may result in a mediastinal mass in any part of the mediastinum. Malignant aetiology is more common in older patients and patients with a prior history of cancer. Haematological malignancies such as Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia may have associated B symptoms, including fever, rash, night sweats, and weight loss.

Acute lymphocytic leukaemia presents with acute onset of symptoms such as fatigue, bleeding, and recurrent infections, due to cytopenias.

Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma is a sub-type of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. It presents as a bulky mass in the prevascular (anterior) mediastinum with symptoms related to compression of adjacent structures, such as the superior vena cava (SVC), which can result in venous congestion of the head and upper extremities causing SVC syndrome.[7]

Thoracic aortic aneurysm

Thoracic aortic aneurysm is a localised or diffuse dilation of the aorta involving all layers of the vessel wall. It may present as a mediastinal mass in the visceral (middle) or paravertebral (posterior) mediastinum. Ascending aortic aneurysms are often caused by cystic medial degeneration or necrosis, which is often associated with collagen vascular disorders. Descending aortic aneurysms are most often associated with atherosclerotic disease. The natural history of thoracic aortic aneurysms involves continued gradual expansion and increased risk for eventual rupture if left untreated.[8][9]

Thymic masses (thymic neoplasm, thymic hyperplasia)

Thymic neoplasms, including thymoma and thymic carcinoma, account for 30% of prevascular (anterior) mediastinal masses in adults and 15% of prevascular (anterior) mediastinal masses in children.[10][11]

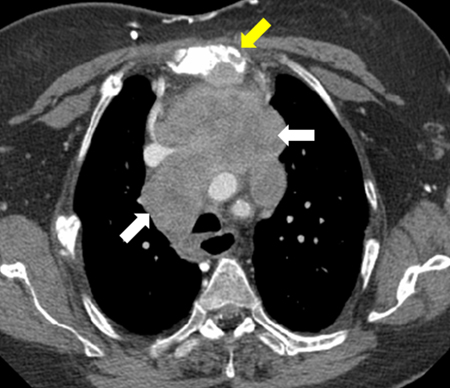

WHO classification of thymic tumours is used to classify thymic neoplasms into Types A, AB, B, or C (thymic carcinoma), with increasingly worse prognosis.[12] The Masaoka-Koga staging scheme for thymomas is often used to describe the extent of local extension.[13] Thymic neoplasms can occur in all age groups, although they have a higher incidence in older people and have a slight male predominance.[14][15][16][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT image of large thymic carcinoma (white arrow) with sternal invasion (yellow arrow)From the collections of Dr Mario Gasparri and Dr Nicholas Choong [Citation ends].

Mediastinal germ cell tumours

Extragonadal germ cell tumours are found along the body's midline and correspond to the embryological urogenital ridge. Mediastinal germ cell tumours constitute 50% to 70% of all extragonadal germ cell tumours, and present in the anterior mediastinum.[17][18] They are classified as benign or malignant. Benign mediastinal germ cell tumours include mature teratoma. Malignant mediastinal germ cell tumours include seminomas (dysgerminomas) and non-seminomas.

Mature teratomas can occur in any age group but are more common in children or young adults.[19] There is no gender predilection for mature teratoma.

Pure seminoma germ cell tumours account for 35% of malignant germ cell tumours.[20]They occur in younger adults aged 20 to 40 years, with a male predominance.

Non-seminoma germ cell tumours include choriocarcinoma, embryonal carcinoma, teratoma, and endodermal sinus tumours.[21] They occur in younger adults aged 20-40 years and have a strong male predominance. They can be associated with Klinefelter's syndrome.[22]

The distinction between seminomatous and non-seminomatous germ cell tumours influences the treatment approach. Therefore, when these aetiologies of mediastinal mass are suspected, a biopsy is usually performed to guide the treatment strategy.

Cyst (bronchogenic, pericardial, oesophageal)

Bronchogenic, pericardial, and oesophageal cysts may present as a mass in the visceral (middle) mediastinum. Although neoplastic transformation has been reported, this is generally not their natural history. Symptoms are related to compression of adjacent structures, haemorrhage, or infection of the cyst.

Bronchogenic and oesophageal cysts are embryonic bronchopulmonary or foregut malformations. These are often removed once identified radiographically.

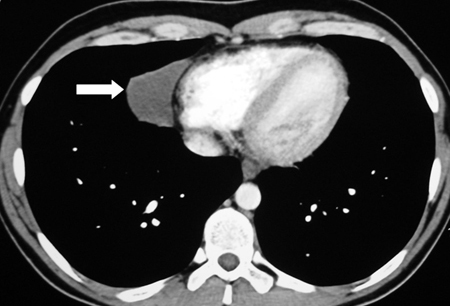

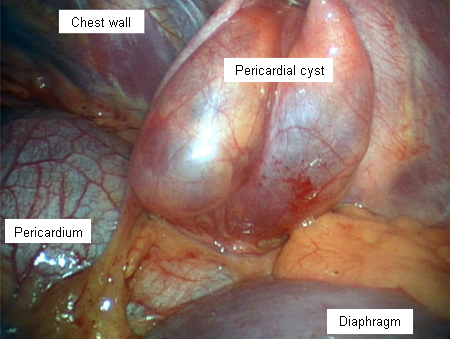

Pericardial cysts are thin-walled cysts that arise from the pericardium, and can be congenital or acquired. These are often not intervened upon unless enlarging or causing symptoms from adjacent compression.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT image of pericardial cystFrom the collections of Dr Mario Gasparri and Dr Nicholas Choong [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intra-operative view of pericardial cystFrom the collections of Dr Mario Gasparri and Dr Nicholas Choong [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intra-operative view of pericardial cystFrom the collections of Dr Mario Gasparri and Dr Nicholas Choong [Citation ends].

Tracheal tumours (benign or malignant)

Primary tracheal tumours can be benign or malignant and may present in the visceral (middle) mediastinum. The majority of tracheal tumours are malignant, with adenoid cystic carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma being the most common histologies.[23] The most common benign tracheal neoplasm is squamous papilloma. Ninety percent of tracheal tumours in adults are malignant, compared with 10% to 30% in children.[24]

Neurogenic tumours (paraganglioma)

Neurogenic tumours arise from peripheral nerves, autonomic ganglia, and embryonic remnants of the neural tube. They may be benign or malignant and may present in the paravertebral (posterior) mediastinum. Neurogenic tumours in children are often malignant, while tumours in adults tend to be benign.[25] Children and young adults are more prone to tumours of autonomic ganglia (two-thirds of which are malignant). Adults are more prone to nerve sheath tumours, which are almost all benign. Benign tumours include neurilemmoma, schwannoma, phaeochromocytoma, neurofibroma, ganglioneuroma, and granular cell tumour. Malignant tumours include malignant schwannoma and neuroblastoma.

Lung cancer

Lung cancer often metastasises to mediastinal lymph nodes, which represents stage III lung cancer. Thorough mediastinal staging is essential for establishing appropriate therapy and prognosis.[26][27] Small cell lung cancer is associated with early and bulky hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy that may be more impressive than lung findings on axial imaging.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer