Approach

The pathological triad consists of tissue eosinophilia, granulomatous inflammation, and vasculitis. EGPA should be considered in patients with refractory asthma when associated with eosinophilia >10% of the WBC count, or when associated with other signs or symptoms of systemic inflammation. It should also be considered in any work-up of hypereosinophilia and in patients who present with a non-specified form of vasculitis. The goals of any diagnostic work-up are to:

Firmly establish the diagnosis

Establish extent and severity of organ involvement to guide treatment

Define baseline and establish markers to assess response to treatment.

The EGPA Consensus Task Force, a group commissioned by the European Respiratory Society and the Foundation for the Development of Internal Medicine in Europe, published a consensus statement on the management and treatment of EGPA, including a detailed differential diagnosis work-up.[28] For patients who have asthma, eosinophilia, and evidence for eosinophilic inflammation (e.g., myocarditis), but not evidence for clear cut vasculitis, the European Respiratory Society Task Force on eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) has suggested that the term hypereosinophilic asthma with (any) systemic manifestations should be used rather than EGPA.[29]

History

Patients typically present with a history of asthma, allergic rhinitis, or sinusitis, with symptoms such as shortness of breath, cough, and wheezing. These pulmonary symptoms may be a manifestation of asthma. However, they may reflect underlying alveolar haemorrhage, which may be accompanied by haemoptysis, or thromboembolic disease. Patients may present with a new-onset sensory or motor deficit suggesting mononeuritis multiplex, with new-onset weakness such as foot drop, or new-onset numbness of an extremity. A purpuric skin rash of the extremities is commonly seen due to vasculitis. This skin involvement often enables the diagnosis of vasculitis to be made with skin biopsy. These clinical findings may overlap, and may vary according to patient and symptoms. Other symptoms include fatigue, arthralgias, and myalgias, or nasal discharge or stuffiness. About one third of patients may have abdominal pain due to oesophagitis, gastritis, colitis, cholecystitis, or biliary tract vasculitis.

Various medications have been linked to EGPA. These include macrolide antibiotics and quinidine. Whether leukotriene receptor antagonists confer any risk for EGPA is controversial. Evidence points towards these agents unmasking previously unrecognised underlying EGPA, either by facilitating systemic glucocorticoid withdrawal, thereby allowing the full syndrome to develop, or by preventing control of the disease as the patient's symptoms progress.[18][19][20]

Physical examination

Clinical assessment of patients with shortness of breath may demonstrate tachypnoea with wheezing associated with asthma, crackles associated with heart failure and pulmonary alveolar haemorrhage, or clear breath sounds associated with thromboembolic disease. Other physical findings of heart failure include orthopnoea, peripheral oedema, and hepatojugular reflux, and may occur in the uncommon situation of vasculitic cardiomyopathy, causing heart failure. A palpable purpuric skin rash with petechiae may be noted, as well as skin nodules, due to granulomas. Isolated motor or sensory deficits, such as foot drop, suggest mononeuritis multiplex. These clinical findings may overlap, and may vary according to patient and symptoms. Purulent, bloody nasal discharge or facial pain may be a manifestation of sinus tract disease. Nasal polyps, nasal obstruction, and recurrent episodes of sinusitis may be noted.

Laboratory tests

No blood test is specific for a diagnosis of EGPA. Testing should include:

FBC with differential to assess eosinophil count, which typically is >10% of the WBC count.

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA): are increased in 30% to 40% of patients with EGPA. Typically a perinuclear-ANCA, myeloperoxidase positive pattern.[4][5][16]

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and CRP as general markers of inflammation. These are usually increased in the setting of vasculitis, and can be followed to assess response to treatment.

Serum chemistries, focusing on urea and creatinine, and urinalysis, which are helpful in assessing for renal involvement.

Serum IgE is generally increased in EGPA. If increased, further specific IgE and IgG testing for Aspergillus should be performed to rule out allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.[28]

HIV testing, as HIV may cause mild eosinophilia.[28]

Testing for the differential diagnosis of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome includes molecular testing for the FIP1L1/PDGFR alpha mutation (leading to the formation of a novel tyrosine kinase, which can be therapeutically targeted by imatinib) and flow cytometry. This is done routinely in some tertiary level care centres, and should be considered in patients with more subtle vasculitic findings. Occasionally, bone marrow biopsy is required.[30][31] It is also not performed routinely, except in tertiary care institutions, and should be considered in patients with more subtle vasculitic findings.

In the appropriate clinical setting, stool cultures may be needed to rule out parasitic infection. Toxocara serology should also be considered.[28]

Eotaxin-3 is an emerging serum marker which is elevated in active EGPA, but is not yet measured in routine clinical practice.[32][33]

Before starting azathioprine, patients often have their thiopurine methyltransferase levels checked, where available, to ensure that they have sufficient enzyme levels to metabolise the drug.

Physiological testing and imaging

Typically, pulmonary function testing will show reversible airway obstruction consistent with asthma, which co-exists in many cases.

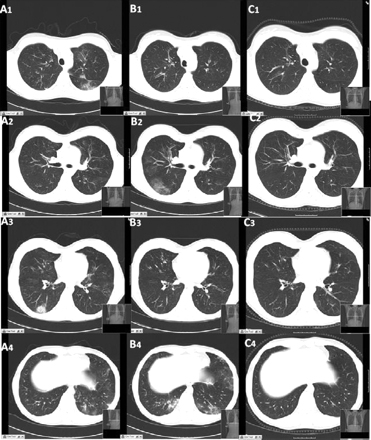

A chest x-ray should be performed on all patients, looking for any evidence that would be consistent with eosinophilic pneumonia or alveolar haemorrhage. If abnormalities are seen, the patient should have a CT scan of the chest.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest obtained (A) during symptom exacerbation, revealing pulmonary infiltrates in the right inferior lobe (A3) and the left inferior lobe (A4). Re-evaluation 15 days later (B) revealed the migratory character of the lesions, with complete disappearance of the previously described infiltrates and the presence of new areas of ground glass opacities within the right inferior lobe (B2) and the left lingular and left inferior lobe (B4). (C) Six months after treatment, all the lung lesions described had healed completelyBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.04.2009.1731. Copyright © 2011 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].

Patients in whom there is a high suspicion of EGPA, or known EGPA who have shortness of breath, should have an ECG to screen for cardiac involvement.[24][34]

The role of cardiac MRI is being investigated.

Patients with active EGPA are at increased risk of thromboembolic disease. Lower extremity ultrasound or CT angiography of the lungs should be performed if clinically indicated.[35][36]

A presumptive diagnosis of mononeuritis multiplex can be made on the basis of an electromyogram, and may be a surrogate marker for vasculitis.

Pathology

When possible, a tissue biopsy that shows evidence of vasculitis should be obtained. Generally this should be obtained from the most easily accessible organ. A purpuric skin lesion is most often biopsied. This typically shows leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Severe involvement of the kidneys or lungs would indicate a need for aggressive therapy, and samples should be obtained from these organs if there is a question of their involvement. Alveolar haemorrhage can be diagnosed with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) at bronchoscopy in the right clinical setting. The characteristic finding would be blood aliquots of lavage fluid, with or without increased haemosiderin-laden macrophages. A diagnosis of vasculitis is seldom made with transbronchial biopsy.

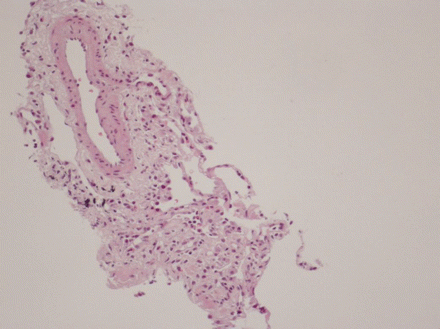

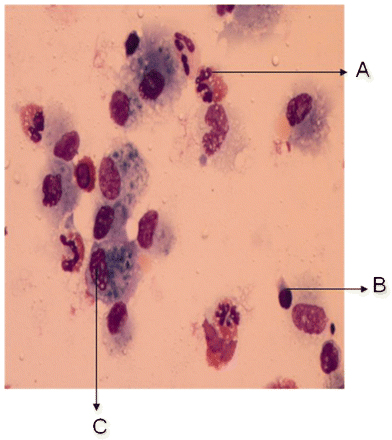

Eosinophilic pneumonia can be diagnosed at bronchoscopy on the basis of a high eosinophil count on BAL, or eosinophilic inflammation on transbronchial biopsy.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histological evaluation of the lung biopsy specimen, revealing the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate composed predominantly of eosinophils found within both the vascular lumen and the vascular wallBMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.04.2009.1731. Copyright © 2011 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cytological examination of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, revealing the presence of a vast predominance of eosinophils (A), representing 27% of the cellular elements. The other cellular elements found were macrophages (C) and lymphocytes (B)BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.04.2009.1731. Copyright © 2011 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cytological examination of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, revealing the presence of a vast predominance of eosinophils (A), representing 27% of the cellular elements. The other cellular elements found were macrophages (C) and lymphocytes (B)BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.04.2009.1731. Copyright © 2011 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer