Isolation of the fungus together with typical clinical and/or radiological findings forms the basis of the diagnosis.

Inhalation of spores is considered the primary route of inoculation, resulting in pulmonary involvement with the potential for subsequent systemic dissemination. In immunosuppressed patients, haematogenous dissemination can occur to multiple organs, including the central nervous system (CNS) and meninges, skin, prostate, eyes, bone, urinary tract, and blood.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

Extrapulmonary infection, especially that involving the CNS, is life-threatening and must always be considered, particularly in immunodeficient patients, even if there are no specific clinical signs of disseminated infection.

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of cryptococcosis varies from asymptomatic infection to life-threatening pneumonia and is different in HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected patients.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Perfect JR, Casadevall A. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002 Dec;16(4):837-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12512184?tool=bestpractice.com

Presenting features

Patients with acute pulmonary cryptococcosis present with pyrexia, a productive cough, dyspnoea, chest pain, weight loss, and fatigue. They may also present with acute respiratory failure.

Headache, fever, cranial neuropathies, alteration of consciousness, lethargy, meningeal irritation, and coma represent CNS involvement and can present over several days or over months. A high index of suspicion should be maintained in HIV-infected patients and immunocompromised patients, even with headache alone, due to the subacute onset and non-specific presentation of meningoencephalitis in these patients. Seizures may be a presenting factor in 15% of patients with HIV-related cryptococcal meningitis.[34]Pastick KA, Bangdiwala AS, Abassi M, et al. Seizures in human immunodeficiency virus-associated cryptococcal meningitis: predictors and outcomes. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019 Nov;6(11):ofz478.

https://academic.oup.com/ofid/article/6/11/ofz478/5613202

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32042847?tool=bestpractice.com

HIV-associated cryptococcosis is characterised by more CNS and extrapulmonary involvement and presents with a higher burden of organisms.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

It is also associated with a poor inflammatory reaction at the site of infection.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

In HIV-positive patients, symptoms typically occur over a period of 1 to 2 weeks or more. Patients without HIV infection have symptoms for a longer period, usually several months, prior to diagnosis.

Obtain past medical and drug history, as symptomatic disease usually develops in immunocompromised patients and those with severe comorbidities.

HIV infection, organ transplantation, idiopathic CD4 lymphocytopenia, liver disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, diabetes mellitus, haematological malignancies, and immunosuppressant medication such as corticosteroids or monoclonal antibodies (e.g., alemtuzumab and infliximab) can all allow reactivation of a cryptococcal infection.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination

Dullness to percussion, diminished breath sounds, and crackles on the affected side represent pleural effusion, diffuse alveolar and interstitial infiltrates, or endobronchial lesions.

Meningeal irritation characterised by neck stiffness, photophobia, and vomiting is seen in one quarter to one third of HIV-positive patients with meningoencephalitis.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Perfect JR, Casadevall A. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002 Dec;16(4):837-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12512184?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Jarvis JN, Harrison TS. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Apr;29(2):141-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18365996?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Haddow LJ, Colebunders R, Meintjes G, et al. Cryptococcal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-1-infected individuals: proposed clinical case definitions. Lancet Inf Dis. 2010 Nov;10(11):791-802.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3026057

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21029993?tool=bestpractice.com

Cranial nerve palsies can also occur.

Papilloedema is a sign of increased intracranial pressure, which may result from meningeal inflammation, cryptococcoma, or hydrocephalus. It occurs in almost 50% of HIV-negative and HIV-positive patients with cryptococcal meningitis, and it complicates management, leading to visual or hearing loss.[35]Haddow LJ, Colebunders R, Meintjes G, et al. Cryptococcal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-1-infected individuals: proposed clinical case definitions. Lancet Inf Dis. 2010 Nov;10(11):791-802.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3026057

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21029993?tool=bestpractice.com

The most common ocular manifestations include retinal and peripapillary haemorrhages, and other retinal lesions, all of which can result in visual loss.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

Cutaneous infections resulting from direct inoculation or secondary to disseminated disease are the third most common clinical site of cryptococcosis, especially in immunocompromised patients. Common skin lesions in HIV-positive patients are molluscum contagiosum-like and acneiform lesions. Purpura, vesicles, nodules, abscesses, ulcers, granulomas, draining sinuses, and cellulitis have also been described.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

Cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide antigen (CrAg) and cultures

Direct examination of the Cryptococcus fungus in body fluids along with cytology, histopathology of infected tissues, serological studies, and culture are necessary for the diagnosis of cryptococcosis and should be carried out in all patients.

CrAg can be detected in blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and pleural fluid using rapid antigen tests. Rapid diagnosis is facilitated by the cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) lateral flow assay (LFA) for serum and CSF, complementing traditional microscopy (India ink staining) and culture techniques.[32]Chang CC, Harrison TS, Bicanic TA, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of cryptococcosis: an initiative of the ECMM and ISHAM in cooperation with the ASM. Lancet Infect Dis. 9 Feb 2024 [Epub ahead of print].

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38346436?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, et al. Guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2024 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin Infect Dis. 5 Mar 2024 [Epub ahead of print].

https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciae104/7619499

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38442248?tool=bestpractice.com

A lateral flow assay (LFA) is a point-of-care rapid diagnostic test that provides results within 10 minutes. Plasma, serum, whole blood, or CSF can be tested.[37]Binnicker MJ, Jespersen DJ, Bestrom JE, et al. Comparison of four assays for the detection of cryptococcal antigen. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012 Dec;19(12):1988-90.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3535868

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23081814?tool=bestpractice.com

Validation of one available CrAg LFA has shown sensitivity of 99.3% and specificity of 99.1%.[38]Boulware DR, Rolfes MA, Rajasingham R, et al. Multisite validation of cryptococcal antigen lateral flow assay and quantification by laser thermal contrast. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 Jan;20(1):45-53.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3884728

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24378231?tool=bestpractice.com

Latex agglutination (latex particles coated with polyclonal cryptococcal capsular antibodies), a direct antigen detection assay, is performed on blood, CSF, or body fluids such as pleural fluid and bronchoalveolar lavage samples. Latex agglutination sensitivity ranges from 97.0% to 97.8%, and specificity ranges from 85.9% to 100%.[38]Boulware DR, Rolfes MA, Rajasingham R, et al. Multisite validation of cryptococcal antigen lateral flow assay and quantification by laser thermal contrast. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 Jan;20(1):45-53.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3884728

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24378231?tool=bestpractice.com

False-positive results may occur due to the presence of rheumatoid factor or infections with Trichosporon beigelii, Stomatococcus mucilaginosus, Capnocytophaga canimorsus, or Klebsiella pneumoniae.[39]Chanock SJ, Toltzis P, Wilson C. Cross-reactivity between Stomatococcus mucilaginosus and latex agglutination for cryptococcal antigen. Lancet. 1993 Oct 30;342(8879):1119-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8105345?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]McManus EJ, Jones JM. Detection of a Trichosporon beigelii antigen cross-reactive with Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide in serum from a patient with disseminated Trichosporon infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1985 May;21(5):681-5.

https://jcm.asm.org/content/21/5/681.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3889042?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Westerink MA, Amsterdam D, Petell RJ, et al. Septicemia due to DF-2. Cause of a false-positive cryptococcal latex agglutination result. Am J Med. 1987 Jul;83(1):155-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3605167?tool=bestpractice.com

False-negative results are caused by a low fungal burden.

Serum CrAg is generally universally positive in patients with HIV infection and cryptococcal meningitis, and CSF involvement becomes increasingly probable as serum CrAg titres increase above 1:160 (LFA). At a serum titre of >1:1280, or >1:640 (LFA) in patients with HIV, even if CSF is CrAg negative, CNS brain parenchymal involvement should be assumed.[20]Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: cryptococcosis. July 2021 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/cryptococcosis?view=full

[42]Rajasingham R, Boulware DR. Cryptococcal antigen screening and preemptive treatment-how can we improve survival? Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Apr 10;70(8):1691-4.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7145997

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31179484?tool=bestpractice.com

In pulmonary cryptococcosis, serum CrAg is usually negative if the infection is confined to the lung with ≤1 cm nodule. A positive result may indicate disseminated disease. Serial fluctuations in serum CrAg titres should not be used to guide treatment, as the kinetics of CrAg elimination remain unclear.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]Pullen MF, Kakooza F, Nalintya E, et al. Change in plasma cryptococcal antigen titer is not associated with survival among human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons receiving preemptive therapy for asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jan 2;70(2):353-5.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6938973

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31119280?tool=bestpractice.com

A rise in CSF CrAg titres during suppressive therapy is associated with relapse in HIV-positive patients with cryptococcal meningitis.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

There is a correlation between initial CSF antigen titres and the burden of yeast in the CNS in quantitative cultures.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Perfect JR, Casadevall A. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002 Dec;16(4):837-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12512184?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Jarvis JN, Harrison TS. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Apr;29(2):141-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18365996?tool=bestpractice.com

The presence of CrAg in the pleural fluid can be useful when cultures are negative.[44]Young EJ, Hirsh DD, Fainstein V, et al. Pleural effusions due to Cryptococcus neoformans: a review of the literature and report of two cases with cryptococcal antigen determinations. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980 Apr;121(4):743-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6992663?tool=bestpractice.com

CrAg titres, in general, cannot be followed over time to monitor treatment response. CrAg may remain positive for years.[43]Pullen MF, Kakooza F, Nalintya E, et al. Change in plasma cryptococcal antigen titer is not associated with survival among human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons receiving preemptive therapy for asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jan 2;70(2):353-5.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6938973

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31119280?tool=bestpractice.com

Cultures

Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus var. gattii can be grown from biological samples, and colonies are observed on solid agar plates after 48 to 72 hours' incubation at 30°C (86°F) to 35°C (95°F) in aerobic conditions.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

Samples from patients treated with systemic antifungal therapy may require more time to produce visible colonies.

Blood cultures may be positive in up to 50% of patients with HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis.[20]Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: cryptococcosis. July 2021 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/cryptococcosis?view=full

Negative CSF cultures in patients with cryptococcal meningitis may be caused by a low fungal burden. Bronchial secretions and urine can be contaminated by many micro-organisms that may mask the growth of cryptococci, especially in patients with AIDS. Prostatic massage can improve fungal detection on urine culture.

Although the Cryptococcus species is not considered normal respiratory flora in humans, it can occasionally colonise the respiratory tract of patients with lung disease, and sputum cultures may be positive. In immunocompromised patients, all isolates must be considered significant, as they have the potential to cause dissemination.

HIV antibodies

As de novo cryptococcal meningitis or disseminated disease usually occurs in HIV-positive patients, testing for HIV antibodies in patients with unknown HIV status who present with cryptococcal meningitis or disseminated disease is recommended.[32]Chang CC, Harrison TS, Bicanic TA, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of cryptococcosis: an initiative of the ECMM and ISHAM in cooperation with the ASM. Lancet Infect Dis. 9 Feb 2024 [Epub ahead of print].

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38346436?tool=bestpractice.com

Chest x-ray and CT chest

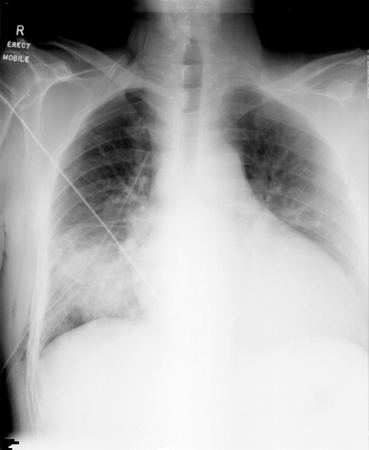

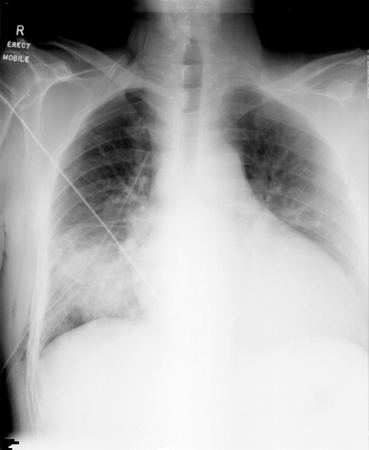

Radiological features of pulmonary cryptococcosis vary widely according to the immune state of the patient and include nodules, consolidation, cavitation, lobar infiltrates, hilar lymphadenopathy, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, pleural effusions, and collapse. Chest computed tomography (CT) reveals the radiological features in more detail and may be indicated in all patients, but especially in immunocompromised patients suspected for pulmonary cryptococcosis. Immunocompetent patients present with discrete nodules, whereas alveolar and interstitial infiltrates, cavitations, pleural disease, and collapse are more commonly seen in immunocompromised patients.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Jarvis JN, Harrison TS. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Apr;29(2):141-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18365996?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Chang WC, Tzao C, Hsu HH, et al. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: comparison of clinical and radiographic characteristics in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Chest. 2006 Feb;129(2):333-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16478849?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Piyavisetpat N, Chaowanapanja P. Radiographic manifestations of pulmonary cryptococcosis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005 Nov;88(11):1674-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16471118?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral cannonball lesions secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pulmonary nodules in right lower lobe and left lower lobe secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pulmonary nodules in right lower lobe and left lower lobe secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bibasal pneumonic consolidation secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bibasal pneumonic consolidation secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral patchy opacification in mid-to-lower zones secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral patchy opacification in mid-to-lower zones secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends].

Neuroimaging

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain detects significantly more cryptococcosis-related lesions than CT.[47]Charlier C, Dromer F, Leveque C, et al. Cryptococcal neuroradiological lesions correlate with severity during cryptococcal meningoencephalitis in HIV-positive patients in the HAART era. PLoS One. 2008 Apr 16;3(4):e1950.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2293413

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18414656?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]Wehn SM, Heinz ER, Burger PC, et al. Dilated Virchow-Robin spaces in cryptococcal meningitis associated with AIDS: CT and MR findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989 Sep-Oct;13(5):756-62.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2778132?tool=bestpractice.com

Radiological features include single or multiple focal mass lesions in cryptococcoma, granulomas without significant mass effect, cysts (gelatinous pseudocysts), hydrocephalus, dilated Virchow-Robin spaces, and enhancing cortical nodules. Cryptococcus var. gattii has a predilection to cause disease in the brain parenchyma rather than the meninges, resulting in cerebral cryptococcomas (represented by single or multiple focal mass lesions) or hydrocephalus.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

Lumbar puncture

Direct microscopic examination of the CSF for the presence of encapsulated yeasts with India ink is a rapid and inexpensive diagnostic test for cryptococcal meningitis.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Perfect JR, Casadevall A. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002 Dec;16(4):837-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12512184?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Jarvis JN, Harrison TS. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Apr;29(2):141-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18365996?tool=bestpractice.com

However, many laboratories no longer perform the India ink test, and its usefulness in the management of cryptococcal meningitis is limited.[20]Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: cryptococcosis. July 2021 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/cryptococcosis?view=full

India ink staining allows detection of yeasts in a CSF specimen when more than 10³ yeasts/mL are present, and shows encapsulated yeast in 60% to 80% of cases.[20]Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: cryptococcosis. July 2021 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/cryptococcosis?view=full

In non-HIV cryptococcal meningitis, the sensitivity is 30% to 50%, while in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis it is up to 80%.[20]Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: cryptococcosis. July 2021 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/cryptococcosis?view=full

Myelin globules, fat droplets, lysed lymphocytes, and lysed tissue cells can cause false-positive results.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

Laboratory analysis of the CSF generally reveals slightly elevated protein levels, low-to-normal glucose levels, and sometimes leukocytosis.[20]Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: cryptococcosis. July 2021 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/cryptococcosis?view=full

Radiographical imaging of the brain with CT or MRI should be undertaken before lumbar puncture in patients with focal neurological signs or papilloedema to identify mass lesions that may contraindicate lumbar puncture.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Perfect JR, Casadevall A. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002 Dec;16(4):837-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12512184?tool=bestpractice.com

Asymptomatic immunocompetent patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis and a negative serum CrAg do not necessarily require a lumbar puncture to rule out CNS disease. Immunocompromised patients should undergo a lumbar puncture regardless of symptoms, particularly when the serum CrAg titre is ≥1:160, and have the CSF tested for CrAg to rule out concomitant CNS infection.[42]Rajasingham R, Boulware DR. Cryptococcal antigen screening and preemptive treatment-how can we improve survival? Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Apr 10;70(8):1691-4.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7145997

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31179484?tool=bestpractice.com

Elevated intracranial pressure, defined as an opening pressure of >20 cm H₂O, measured with the patient in the lateral decubitus position, occurs in up to 80% of patients with cryptococcal meningitis and is associated with a poorer clinical response.[23]World Health Organization. Guidelines for diagnosing, preventing and managing cryptococcal disease among adults, adolescents and children living with HIV. June 2022 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240052178

[49]Kambugu A, Meya DB, Rhein J, et al. Outcomes of cryptococcal meningitis in Uganda before and after the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Jun 1;46(11):1694-701.

https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/46/11/1694/375206

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18433339?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Bicanic T, Brouwer AE, Meintjes G, et al. Relationship of cerebrospinal fluid pressure, fungal burden and outcome in patients with cryptococcal meningitis undergoing serial lumbar punctures. AIDS. 2009 Mar 27;23(6):701-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19279443?tool=bestpractice.com

[51]Meda J, Kalluvya S, Downs JA, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis management in Tanzania with strict schedule of serial lumber punctures using intravenous tubing sets: an operational research study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014 Jun 1;66(2):e31-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24675586?tool=bestpractice.com

Opening pressures ≥25 cm H₂O may be detected in 60% to 80% of HIV-positive patients with cryptococcal meningitis.[20]Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: cryptococcosis. July 2021 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/cryptococcosis?view=full

US guidelines recommend measuring opening pressure at diagnosis in all patients with suspected cryptococcal meningitis.[20]Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: cryptococcosis. July 2021 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/cryptococcosis?view=full

Bronchoscopy

CrAg testing and cultures of bronchoalveolar lavage samples and washings may be positive in pulmonary cryptococcosis.[4]Jarvis JN, Harrison TS. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Apr;29(2):141-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18365996?tool=bestpractice.com

CrAg testing in bronchoalveolar lavage samples is highly effective in diagnosing cryptococcal pneumonia with a titre >1:8, having 100% sensitivity and 98% specificity.[4]Jarvis JN, Harrison TS. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Apr;29(2):141-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18365996?tool=bestpractice.com

Biopsy

Histological examination of lung, skin, bone marrow, brain, or prostatic tissue can also be undertaken to detect systemic dissemination. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) specimens obtained from the lymph nodes and adrenal glands can be used for cytological study. Percutaneous transthoracic FNA of pulmonary nodules or infiltrative lesions, under ultrasound or CT guidance, can be performed to diagnose pulmonary cryptococcosis. Other specimens for cytological examination include bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, centrifuged CSF, vitreous aspiration fluid, and seminal fluid.[1]Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006 Sep;20(3):507-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16984867?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Perfect JR, Casadevall A. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002 Dec;16(4):837-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12512184?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Jarvis JN, Harrison TS. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Apr;29(2):141-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18365996?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, et al. Guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2024 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin Infect Dis. 5 Mar 2024 [Epub ahead of print].

https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciae104/7619499

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38442248?tool=bestpractice.com

Emerging investigations

The BioFire® FilmArray® polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay is available in the US for the detection of cryptococcal infection in the CSF.[20]Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: cryptococcosis. July 2021 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/cryptococcosis?view=full

The assay may give false-negative results if fungal burden is low, so it should not be used as a diagnostic test in isolation.[20]Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: cryptococcosis. July 2021 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/cryptococcosis?view=full

PCR is likely to be most useful in differentiating a second episode of cryptococcal meningitis (PCR positive) from immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (PCR negative) in patients with HIV.[20]Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: cryptococcosis. July 2021 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/cryptococcosis?view=full

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pulmonary nodules in right lower lobe and left lower lobe secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pulmonary nodules in right lower lobe and left lower lobe secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bibasal pneumonic consolidation secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bibasal pneumonic consolidation secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral patchy opacification in mid-to-lower zones secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral patchy opacification in mid-to-lower zones secondary to Cryptococcus neoformansFrom the collection of the radiology department, The Prince Charles Hospital, Chermside, Brisbane, Australia; used with permission [Citation ends].