Primary prevention

Immunisation remains the cornerstone of primary prevention. There are two main types of poliovirus vaccine: the inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) (Salk) and oral attenuated poliovirus vaccine (OPV) (Sabin). IPV is administered by injection but is the vaccine of choice in countries considered polio-free, due to the risk of vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP) and circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) from OPV.[23] IPV is favoured in the few studies assessing the benefits of polio vaccination in post-eradication settings.[29] In developing countries, however, OPV remains the mainstay of vaccination; OPVs are easy to administer and can replicate in the intestine, resulting in passive immunisation in areas with poor hygiene and sanitation.[30] Repeated rounds of immunisation may be needed before immunity is conferred. There is little cross-immunity between poliovirus strains, so the vaccine must contain the strains circulating in the endemic area or causing outbreaks.

In the UK, poliovirus vaccination is usually given to babies as part of the DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB vaccine (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis/polio/Haemophilus influenzaeb/hepatitis B vaccine) at 2, 3, and 4 months old, with one booster given at age 3 years 4 months (as part of the DTaP/IPV pre-school booster) and one at 14 years (as part of tetanus, diphtheria [Td]/IPV teenage booster).[31]

In the US, poliovirus vaccination with IPV is recommended 4 times: at ages 2 months, 4 months, between 6 and 18 months, and between 4 and 6 years of age.[32] A hexavalent vaccine is also approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to prevent diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio,Haemophilus influenzae b, and hepatitis B. The DTaP-IPV-Hib-HepB vaccine is licensed for use in children aged 6 weeks to 4 years and is indicated for the primary vaccination series in infants at ages 2, 4, and 6 months.[33] Doses of OPV administered on or after April 1st 2016 should not be counted towards US vaccination requirements, because OPVs used after this date are not trivalent.

Routine vaccination is not recommended in adults; however, adults may receive poliovirus vaccination or a booster in some situations. In the US, a one-time adult polio vaccine booster is recommended for completely vaccinated adults who are at increased risk of exposure: for example, by travel to certain countries.[3][34][35] It is recommended that adults aged ≥18 years, who are known or suspected to be unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated against polio, complete a primary polio vaccination series with IPV.[35][36]

In the UK, it is recommended that travellers to affected countries should have a poliovirus vaccination, if not fully vaccinated, or should have a booster if it’s been 10 years since the last vaccine dose. National Health Service: Polio Opens in new window Children should maintain up-to-date vaccinations according to the poliovirus vaccination protocol of their country of origin. People travelling from a non-endemic setting to countries where polio is occurring, either caused by wild or vaccine-derived virus, should check they are up to date with their routine polio vaccination series.

The occurrence of VAPP, though rare, or the more frequent occurrence of cVDPV is a major disadvantage of the use of OPV. This vaccine contains attenuated virus that may occasionally become neurotropic, resulting in disease similar to the wild-type virus. For this reason, administration of OPV in children who are immunocompromised, or who have family members who are immunocompromised, is not advised. In some countries, administration of OPV has been replaced by IPV. This is because in these countries it is considered that the risk of paralysis associated with vaccination using OPV is greater than the risk of infection with wild polio virus. High-potency monovalent OPV types 1 (mOPV1) and 3 (mOPV3), and a bivalent OPV type 1 (bOPV1) and 3 (bOPV3) are available for use, while trivalent OPV (types 1, 2, and 3) use has been discontinued and all vaccine stores destroyed.[30] The monovalent type 1 oral poliovirus vaccine was found to be superior to trivalent oral poliovirus vaccine when given to neonates.[37] Novel oral poliovirus vaccines (nOPVs) are more genetically stable and thought to be less likely to be associated with emergence of cVDPV in low immunity settings.[23][38] nOPV2 is currently being used under the World Health Organization’s Emergency Use Listing (EUL) procedure for control of outbreaks caused by type 2 cVDPV in several countries.[23][39]

The Polio Eradication Strategy (2022-2026) advocates the use of bOPV & IPV as part of national immunisation schedules, whilst moving towards complete withdrawal of OPVs to stop the occurrence of VAPP and to eliminate the risks of VDPV.[40] One Cochrane review found that a schedule of IPV followed by OPV reduces the occurrence of VAPP compared with OPV alone.[41]

[  ]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Polio vaccination in AfghanistanFrom the collection of Ellyn Ogden-USAID; used with permission [Citation ends].

]

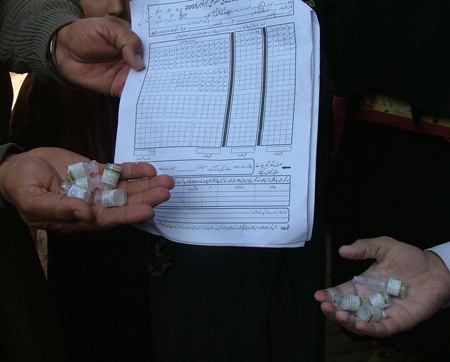

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Polio vaccination in AfghanistanFrom the collection of Ellyn Ogden-USAID; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vials of oral polio vaccine during a vaccination campaign in PakistanFrom the collection of Dr Omar Khan; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vials of oral polio vaccine during a vaccination campaign in PakistanFrom the collection of Dr Omar Khan; used with permission [Citation ends].

Secondary prevention

In the acute phase of the minor illness, remain especially cautious of body fluids coming into contact with unvaccinated individuals. Advocate for improved water and sanitation.

When poliovirus infection is diagnosed or suspected, the local health authority should be immediately notified. In the US, this will be the local health department or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); in disease-endemic countries, the local office of the WHO.[1]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer