Approach

The clinical presentation of poliovirus infection depends on the immune status of the patient and the spread and replication of the virus within the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system. Suspected cases of poliomyelitis, with or without acute flaccid paralysis, should be reported to the local health authority. Pursuant to the International Health Regulations, all signatory countries are required to inform the WHO of polio cases.[1] In addition, reporting to the WHO of wild virus found in environmental sampling is mandatory (this is generally done by the local health authorities). Acute poliomyelitis is a notifiable disease in the UK.

History

Key historical factors to help rule in the diagnosis of paralytic polio include age <36 months, unimmunised status, residence in or travel from a poliovirus-endemic country, and a gastrointestinal prodrome. Patients who are immunocompromised due to congenital or acquired immunodeficiency are more susceptible to infection from vaccine-attenuated virus present in the oral form of poliovirus vaccine.

Most cases of poliovirus infection are asymptomatic (90% to 95%), but some children will have symptoms in keeping with viral gastroenteritis, including fatigue, fever, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea, usually lasting no more than 5 days. Some patients may complain of sore throat, and also of headache and photophobia, a manifestation of meningeal irritation.

Less than 1% of infected individuals will present with acute flaccid paralysis (AFP). Intramuscular injections during the incubation period have been associated with AFP. Clinical features initially may include fatigue, fever, nausea, vomiting (all characteristics of the minor illness); these then may proceed to the major illness, typically with asymmetrical lower limb weakness and flaccidity. The maximum extent of paralysis is reached within a week of onset of symptoms of paralysis.

A minority of affected cases with AFP progress to life-threatening bulbar paralysis and respiratory compromise.[1][42]

A post-poliomyelitis syndrome (PPS) may develop years or even decades following acute poliomyelitis; patients complain of fatigue, weakness, and wasting of the muscles. This condition usually involves muscle groups previously affected in the original illness.[42][43]

Examination

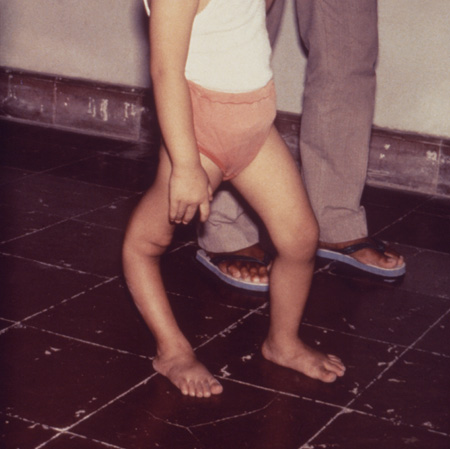

Children with a mild illness and viral gastroenteritis may show signs of volume depletion and fever with abdominal pain. Physical exam features that support a diagnosis of paralytic poliomyelitis include asymmetrical paralysis or significant loss of motor function of extremities, especially the legs. In general, there is preserved sensation, decreased deep tendon reflexes on the affected limb, and, eventually, atrophy of the muscles of the affected limb.[1][42][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Child displaying deformity of her right leg due to poliomyelitisCDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

Respiratory failure due to bulbar paralytic poliomyelitis is a medical emergency and may develop in patients with paralysis. It has a mortality rate of approximately 60%.[28]

Investigations

The diagnosis is made clinically. Diagnosis may also be made by isolation of one of the three strains of poliovirus from stool (most commonly), CSF, or oral secretions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has removed the emphasis on culture as the preferred method for poliovirus testing. Molecular methods, such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), are now considered equally sensitive and do not require consideration of containment issues, making them the preferred approach.[44] Serum antibodies are less helpful, since they may be present in immunised children, or in those previously exposed to poliovirus infection without having developed a symptomatic illness.[1][45]

Individual physicians will typically not find themselves in a situation of collecting samples for polio diagnosis. In the western hemisphere (where polio has been eliminated), the local health authority will coordinate specimen collection. Usually, serum and stool specimens are obtained by the health authority and sent to the US CDC or other regional reference laboratory for testing, and for determination of wild-type versus vaccine-related poliovirus if needed.

It is recommended that serum samples be collected in a red-top or other tube not containing anticoagulant, during the acute phase (i.e., as soon as feasible after the onset of acute flaccid paralysis) and convalescent phase (at least 3 weeks after the acute-phase specimen). Two stool specimens and two throat swabs are usually obtained, in containers appropriate for viral culture. Both should be obtained during the course of the acute illness and at least 24 hours apart. Serological testing is typically for IgG, and stool/throat samples are for viral culture. CSF specimens are not routinely obtained, but may be sent to the laboratory if obtained to rule out another condition such as encephalitis or meningitis.

MRI may help in assessing anterior horn involvement and inflammation of the spinal cord, as well as to rule out other conditions with a similar presentation.[1] It has low utility in the diagnosis of polio. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies may be useful in paralytic poliomyelitis and in post-poliomyelitis syndrome.[43] Although the clinical presentation is adequate to demonstrate paralysis, these study modalities can confirm the physical findings, and they may be useful in investigating other causes of paralysis when post-poliomyelitis syndrome is part of the differential diagnosis.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer